Battle of Blair Mountain facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Blair Mountain |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the West Virginia Coal Wars | ||||

Cover of The Washington Times about the US airfleet sent to West Virginia.

|

||||

| Date | August 25 to September 2, 1921 | |||

| Location |

37°51′45″N 81°51′23″W / 37.86250°N 81.85639°W |

|||

| Resulted in | Law enforcement and military victory

|

|||

| Parties to the civil conflict | ||||

|

||||

| Lead figures | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||

| Number | ||||

|

||||

| Casualties | ||||

|

||||

The Battle of Blair Mountain was the biggest worker uprising in U.S. history. It was also the largest armed conflict since the American Civil War. This event happened in Logan County, West Virginia. It was part of the Coal Wars, which were fights over workers' rights in the early 1900s. These conflicts took place in the Appalachia region. Up to 100 people died, and many more were arrested during this battle.

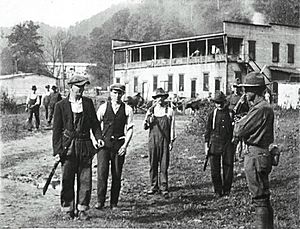

For five days, from late August to early September 1921, about 10,000 armed coal miners faced off against 3,000 law enforcement officers and strikebreakers. These groups were supported by coal mine owners. The miners were trying to form a union in the coalfields of southwestern West Virginia. The battle ended after about one million bullets were fired. The United States Army, including the West Virginia Army National Guard, stepped in. This happened by order of the U.S. President.

Contents

Why the Battle Started

Since 1890, the United Mine Workers union had been trying to organize coal mines. But mines in Mingo County, West Virginia and nearby areas only hired workers who were not part of a union. Their work contracts said that joining a union meant losing your job right away. Miners often lived in company towns, so losing their job also meant losing their home.

In 1920, the new president of the UMW, John L. Lewis, wanted to finally get unions into these areas. He was pressured by miners in other places who were striking. He was also pressured by mine owners who were losing money because non-union mines in West Virginia were cheaper.

Union Efforts and Conflicts

Mother Jones, who was 83 years old, helped with this union push. She gave powerful speeches. Frank Keeney, a local union leader, also helped. More than 3,000 miners in Mingo County joined the union. Because of this, they were all fired. The coal companies then hired agents from the Baldwin–Felts Detective Agency. These agents were known for using force against groups trying to organize. Their job was to remove the fired miners and their families from their homes.

On May 19, 1920, a group of Baldwin–Felts detectives arrived in Matewan. They included Lee Felts and his brother Albert Felts. Albert had tried to pay the mayor of Matewan, Cabell Testerman, to put machine guns in the town. Mayor Testerman refused. That afternoon, the agents went to a coal company property. They forced the first family they found out of their home at gunpoint. They threw the family's belongings into the street. Miners who saw this were very angry and sent word to town.

As the agents walked to the train station, Police Chief Sid Hatfield and a group of miners confronted them. They told the agents they were under arrest. Albert Felts said he had a warrant to arrest Hatfield. Mayor Testerman came out and looked at the warrant. He said, "This is a fake warrant." After these words, a gunfight started. Chief Hatfield shot Albert Felts. Mayor Testerman, Albert, and Lee Felts were among the ten people killed.

This gunfight became known as the Matewan Massacre. It was very important to the miners. The powerful Baldwin–Felts agency had been defeated. Chief Sid Hatfield became a hero to the union miners. He showed them that they could fight back against the coal operators and their hired guards.

Rising Tensions

Throughout the summer and fall of 1920, the union grew stronger in Mingo County. But the coal operators also became more resistant. There were many small shootouts along the Tug River. In late June, state police raided a tent camp where miners lived. Miners reportedly shot at the police. In response, the police shot and arrested miners. They also destroyed the tents and scattered the families' belongings. Both sides were getting more weapons. Sid Hatfield continued to support the resistance. He even turned Testerman's jewelry store into a gun shop.

On January 26, 1921, Hatfield's trial for killing Albert Felts began. It was a big national news story. Hatfield's fame grew during the trial. He talked to reporters and made his story even bigger. In the end, all the men were found not guilty. But the union was facing problems. Most mines had reopened with new workers or former strikers who had agreed not to join the union.

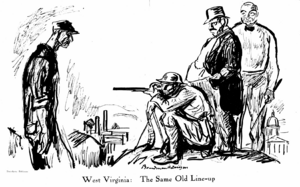

In mid-May 1921, union miners attacked non-union mines. Soon, the entire Tug River Valley was in conflict. This "Three Days Battle" ended when a truce was called. The government then put the area under military rule. Miners felt this rule was unfair. Hundreds of miners were arrested for small reasons. But those on the "law and order" side seemed to be free from punishment. Miners fought back using surprise attacks and damaging property.

In this tense situation, Hatfield went to McDowell County on August 1, 1921. He was going to court for charges related to damaging a coal tipple. His friend Ed Chambers and their wives went with him. As they walked up the courthouse stairs, unarmed, a group of Baldwin–Felts agents opened fire. Hatfield was killed instantly. Chambers was shot many times and fell down the stairs. Even though Sally Chambers protested, one agent ran down and shot Chambers again in the head. Hatfield's and Chambers' bodies were returned to Matewan. News of their deaths spread quickly.

The miners were furious that Hatfield had been killed. They knew the attackers would likely not be punished. Miners began to arm themselves and leave their homes in the mountains. Miners along the Little Coal River were among the first to organize. They started patrolling and guarding their area. Sheriff Don Chafin of Logan County sent his officers to the Little Coal River area. But the armed miners captured the officers, took their weapons, and made them flee.

On August 7, 1921, leaders of the United Mine Workers (UMW) District 17 called a meeting. This district covered much of southern West Virginia. The leaders, Frank Keeney and Fred Mooney, were experienced in past mine conflicts. They met with Governor Ephraim Morgan. They gave him a list of the miners' demands. When Governor Morgan refused their demands, the miners became more upset. They started talking about marching to Mingo County. They wanted to free arrested miners, end military rule, and organize the county. But Blair Mountain, Logan County, and Sheriff Chafin were directly in their way.

The Battle Begins

At a meeting on August 7, Mary Harris "Mother" Jones told the miners not to march into Logan and Mingo counties. She warned them not to try to force the union in. Some people thought she was losing her courage. She feared a terrible fight between the lightly armed union miners and the heavily armed Logan County deputies.

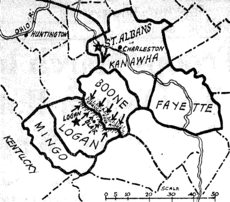

However, the miners felt Governor Morgan had lied to them again. Armed men began gathering at Lens Creek Mountain, near Marmet. This was in Kanawha County. This gathering started on August 20. Four days later, about 13,000 men had gathered. They began marching towards Logan County.

The March and Defenses

Miners near St. Albans were eager to get to the fight. They took over a Chesapeake and Ohio freight train. The miners called it the "Blue Steel Special." They used it to meet up with the main group of marchers at Danville. This was in Boone County, on their way to "Bloody Mingo."

During this time, Keeney and Mooney left for Ohio. The determined Bill Blizzard took on a leadership role for the miners. Meanwhile, Sheriff Chafin, who was against unions, started setting up defenses on Blair Mountain. He received money from the Logan County Coal Operators Association. This allowed him to create the largest private armed force in the country, with nearly 2,000 men.

The first small fights happened on the morning of August 25. Most of the miners were still about 15 miles away. The next day, President Warren G. Harding threatened to send in federal troops and Army bombers. After a long meeting, the miners were convinced to go home. But the fight was not over.

Sheriff Chafin had spent days building his private army. He was determined to have his battle to stop unions from organizing Logan County coal mines. Within hours of the decision to go home, rumors spread. People said Chafin's men had shot union supporters in Sharples. They also said families were caught in the crossfire during the fights. The miners became very angry. They turned back towards Blair Mountain. Many traveled on other stolen trains.

By August 29, the battle was in full swing. Chafin's men were outnumbered, but they had an advantage. They were in higher positions and had better weapons. Private planes were hired to drop homemade bombs on the miners. These bombs included a mix of chemicals and explosives left over from World War I. They were dropped in several places near the towns of Jeffery, Sharples, and Blair. At least one bomb did not explode. Miners found it and used it later as evidence in court.

General Billy Mitchell ordered Army bombers from Maryland to fly over the area. They were used for looking down from the air. One bomber crashed on its way back, killing the three crew members.

Federal Intervention and Aftermath

On August 30, Governor Morgan put Colonel William Eubanks of the West Virginia National Guard in charge. He commanded the government and volunteer forces fighting the miners. Small gun battles continued for a week. At one point, the miners almost broke through to the town of Logan. Their goal was to reach the non-union Logan and Mingo counties to the south.

Reports said up to 30 people on Chafin's side were killed. On the union miners' side, 50–100 were killed. Hundreds more were hurt or wounded. Chafin's forces included 90 men from Bluefield, West Virginia, 40 from Huntington, West Virginia, and about 120 from the West Virginia State Police. Three of Chafin's forces were killed. One miner was also fatally wounded.

Federal troops arrived by September 2. Many miners were veterans themselves. They did not want to shoot at U.S. troops. Bill Blizzard told the miners to start heading home the next day. Miners were afraid of being arrested and losing their guns. They found clever ways to hide their rifles and handguns in the woods before leaving Logan County. Some of these weapons were found later. Many spent and live bullets were also found. These findings helped experts understand how the fighting happened.

After the battle, 985 miners faced serious legal charges. These included charges related to violence and acting against the state of West Virginia. Some were found not guilty by juries who sympathized with them. Others were put in prison for years. The last miner was released in 1925. At Blizzard's trial, the unexploded bomb was used as proof of the government and companies' harsh actions. He was found not guilty.

What Happened Next

At first, the battle was a big win for the coal mine owners. The number of members in the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA or UMW) dropped sharply. It went from over 50,000 miners to about 10,000 in a few years. It wasn't until 1935 that the UMW fully organized in southern West Virginia. This happened after the Great Depression and the start of the New Deal under President Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

This defeat for the union had big effects on the UMWA. After World War I, the coal industry started to struggle. Union mining became too expensive. Because of the loss in West Virginia, the union also became weaker in Pennsylvania and Kentucky. By the end of 1925, Illinois was the only unionized state that could compete in soft coal production.

Over time, the battle made more people aware of the terrible conditions miners faced. It also changed how unions fought for their rights. They started to work more on getting laws on labor's side. This led to a much bigger victory for organized labor a few years later during the New Deal in 1933. This also helped the UMWA organize other well-known unions, like the Steel Workers. It also led to the creation of larger labor groups like the American Federation of Labor (AFL) and Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO).

Protecting the Site

In 2006, a local archeologist named Kenneth King led a team to study the battlefield. King and his team found 15 battle sites. They also discovered over a thousand items, like bullet casings and coins. They found little sign that the site had been disturbed. This went against earlier studies by coal companies that owned mining rights to Blair Mountain.

In April 2008, Blair Mountain was chosen to be on the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP). This list protects important historical places. The site was added to the NRHP on March 30, 2009. But due to some mistakes, it was later removed.

In 2010, National Geographic reported that two large coal companies had permits. These permits allowed them to mine huge parts of Blair Mountain. This would remove much of the mountaintop.

In October 2012, a judge ruled that groups trying to protect the site could not sue. But on August 26, 2014, a higher court overturned this ruling. They sent the case back for another look. In April 2016, a federal court overturned the order to remove the battlefield from the National Register. The decision to add the site back was given to the Keeper of the National Register. On June 27, 2018, the Keeper's Office said the 2009 decision to remove the site was wrong. They confirmed that the site was back on the National Register.

Blair Mountain in Stories and Songs

In Fiction

The Blair Mountain march and the events around it appear in several novels. These include Storming Heaven (1987) by Denise Giardina, Blair Mountain (2006) by Jonathan Lynn, and Carla Rising (2015) by Topper Sherwood. In The Ballad of Trenchmouth Taggart (2008) by Glenn Taylor, the main character meets Sid Hatfield. He is also involved in the Matewan Massacre and the battle.

John Sayles' 1987 film Matewan shows the Matewan Massacre. This was a small part of the larger Blair Mountain story. Diane Gilliam Fisher's poetry book Kettle Bottom also focuses on the Battle of Blair Mountain. It tells the story from the viewpoint of the miners' families.

In Music

Tom Breiding's song "Union Miner" (2008) describes events around the Battle of Blair Mountain. It is told from a coal miner's perspective. This song is often played at events by the United Mine Workers of America today.

"Miners' Rebellion" (2012) by the band The Miners tells the story of the battle. The song is on their first album, also called Miners' Rebellion.

When Miners March (2007) is an audiobook with 16 new songs about the battle.

"Battle of Blair Mountain" (2004) is a song by folk singer David Rovics. It is on his album Songs for Mahmud.

The song "Battle of Blair Mountain" (2010) was written by Louise Mosrie and Mike Richardson. It is on Mosrie's album Home.

The song "Red Neck War" by Byzantine is based on the Battle of Blair Mountain. It is on their 2005 album ... And They Shall Take Up Serpents.

The song "Black Lung" by The Radio Nationals is also based on this conflict.

Blair Pathways (2011) is a project that includes a CD and maps. It tells the history of the Blair Mountain area and its labor disputes. It has music by many traditional artists.

The Irish folk punk band The Fisticuffs released "The Ballad of Bill Blizzard" (2011). It is about the Battle of Blair Mountain.

Kentucky country artist Tyler Childers released "Long Violent History" in 2020. In his comments on the song, he compares the Battle of Blair Mountain to the Black Lives Matter movement.

See also

In Spanish: Batalla de Blair Mountain para niños

In Spanish: Batalla de Blair Mountain para niños

- Anti-union violence in the United States

- Coal strike of 1902

- Colorado Labor Wars

- Copper Country strike of 1913–1914

- Cripple Creek miners' strike of 1894

- Harlan County War

- Illinois coal wars

- List of incidents of civil unrest in the United States

- List of rebellions in the United States

- Labor history of the United States

- Ludlow Massacre

- Mining in the United States

- Molly Maguires

- Railroad Wars

- Range war

- Sheep Wars

- Union violence in the United States

- West Virginia Coal Wars

| Frances Mary Albrier |

| Whitney Young |

| Muhammad Ali |