Black Panther Party facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Black Panther Party

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Abbreviation | BPP |

| Leader | Huey Newton |

| Founded | 1966 |

| Dissolved | 1982 |

| Headquarters | Oakland, California |

| Newspaper | The Black Panther |

| Membership | c. 5,000 (1969) |

| Ideology |

|

| Political position | Far-left |

| Colors | Black |

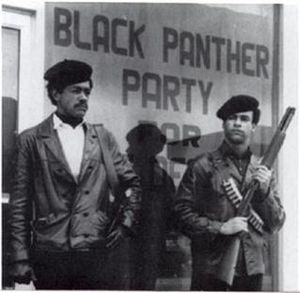

The Black Panther Party (BPP), first called the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense, was a political group started by college students Bobby Seale and Huey P. Newton. They formed it in October 1966 in Oakland, California. The party was active in the United States from 1966 to 1982. They had groups in many big American cities like San Francisco, New York, and Chicago. They also had groups in prisons and even in other countries like Britain and Algeria.

When they first started, a main thing they did was "copwatching." This meant they would openly carry guns and watch the police. They wanted to challenge police using too much force and acting wrongly. From 1969 onwards, the party also created social programs. These included the Free Breakfast for Children Programs, education programs, and community health clinics. The Black Panther Party believed in class struggle, saying they spoke for working-class people.

In 1969, J. Edgar Hoover, who was the head of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), called the party "the greatest threat to the internal security of the country." The government's actions against the party actually helped it grow at first. Many African Americans and people on the political left saw the party as a strong group fighting against unfair separation of races and the military draft. The party had the most members in 1970. Its numbers slowly went down over the next ten years. This was because the news often showed them in a bad light and because of disagreements within the group. These disagreements were often made worse by the FBI's secret COINTELPRO program.

Contents

History of the Black Panther Party

How the Party Started

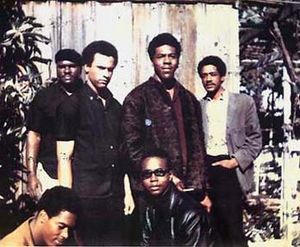

Top left to right: Elbert "Big Man" Howard, Huey P. Newton (Defense Minister), Sherwin Forte, Bobby Seale (Chairman)

Bottom: Reggie Forte and Little Bobby Hutton (Treasurer).

During World War II, many black people moved from the Southern states to cities like Oakland. They went there to find jobs in war factories. This big move changed cities in the Bay Area. A new generation of young black people grew up facing new kinds of poverty and racism. They wanted new ways to deal with these problems. Many Black Panther Party members were from families who moved north or west to escape racism in the South. But they found new forms of unfairness and control in their new cities.

In the early 1960s, the Civil Rights Movement had ended the Jim Crow system of racial separation in the South. This was done using peaceful protests. But not much changed in cities in the North and West. Jobs that had brought black families to these cities moved to the suburbs. Black people were often left in poor city areas with high unemployment and bad housing. They were mostly kept out of politics and good universities. Police departments in the North and West were almost all white. In 1966, less than 2.5% of Oakland's police officers were African American.

Peaceful civil rights actions did not fix these problems. By 1966, a "Black Power" idea grew stronger. Young black people in cities like Oakland wanted to know how black people could get real economic and political power. From these discussions, the Black Panther Party was born.

Founding the Black Panther Party

In October 1966, Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale started the Black Panther Party. They had learned from other Black Power groups. Newton and Seale first met in 1962 when they were students at Merritt College. They read books, debated, and organized. They were inspired by leaders like Malcolm X. They also worked with more active groups that wanted change. Their jobs running youth programs helped them develop ideas for community service. This later became a key part of the Black Panther Party's "community survival programs."

Newton and Seale were not happy that other groups did not directly challenge police brutality. Newton believed that if he could stand up to the police, he could organize people to gain political power. He was inspired by Robert F. Williams's armed resistance against the Ku Klux Klan. Newton studied gun laws in California a lot. He decided to organize patrols to follow the police and watch for bad behavior. But his patrols would carry loaded guns. Huey and Bobby raised money to buy shotguns by selling copies of Mao's Little Red Book. Bobby Seale said they would "sell the books, make the money, buy the guns, and go on the streets with the guns. We'll protect a mother, protect a brother, and protect the community from the racist cops."

On October 29, 1966, Stokely Carmichael, a leader of another group, spoke about "Black Power" in Berkeley. He was promoting a group in Alabama that used a Black Panther symbol. Newton and Seale decided to use the Black Panther logo and form their own group. They chose a uniform of blue shirts, black pants, black leather jackets, and black berets. Sixteen-year-old Bobby Hutton was their first member.

By January 1967, the BPP opened its first office in Oakland. They also published the first issue of The Black Panther: Black Community News Service.

Early Actions (1966-1967)

Oakland Police Patrols

The party's first action was using laws that allowed people to openly carry guns. They did this to protect themselves while watching the police. They would follow police cars from a distance to record any police brutality. If a police officer stopped them, party members would explain the laws that showed they were doing nothing wrong. They would also threaten to take to court any officer who violated their rights. These armed patrols in Oakland's black communities slowly attracted more members. Numbers grew more in February 1967 when the party provided an armed escort for Betty Shabazz, Malcolm X's widow, at the San Francisco airport.

The Black Panther Party's focus on being strong and ready to fight was often seen as being openly hostile. This gave them a reputation for violence. But their early efforts mainly focused on social issues and using their legal right to carry weapons. The Panthers used a California law that allowed carrying a loaded rifle or shotgun as long as it was shown publicly and not pointed at anyone. They did this while watching police behavior in their neighborhoods. The Panthers argued that this strong approach and openly carrying weapons was needed to protect people from police violence. For example, chants like "The Revolution has come, it's time to pick up the gun. Off the pigs!" helped create the Panthers' image as a violent group.

Rallies in Richmond, California

The black community in Richmond, California, wanted protection from police brutality. On April 1, 1967, a 22-year-old black construction worker named Denzil Dowell was shot and killed by police. Dowell's family asked the Black Panther Party for help because officials would not investigate. The Party held rallies in North Richmond. They taught the community about armed self-defense and the Denzil Dowell incident. Police rarely interfered because every Panther was armed and no laws were broken. Many community members agreed with the Party's ideas and brought their own guns to later rallies.

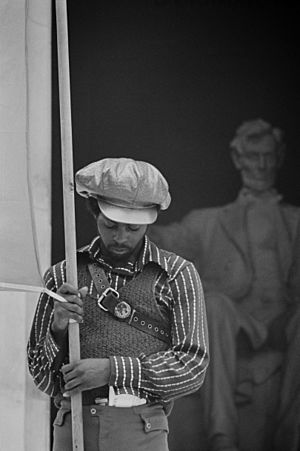

Protest at the Statehouse

More people learned about the Black Panther Party after their protest on May 2, 1967, at the California State Assembly. On that day, the California State Assembly was going to discuss the "Mulford Act." This act would make it illegal to carry loaded firearms in public. Newton and Eldridge Cleaver planned to send 26 armed Panthers, led by Seale, from Oakland to Sacramento to protest the bill. The group entered the assembly carrying their weapons. This event was widely reported in the news. Police arrested Seale and five others. The group admitted to minor charges of disturbing a legislative session. At the time of the protest, the Party had fewer than 100 members.

The Mulford Act was passed by the California government in 1967 and signed by Governor Ronald Reagan. This bill was created because of the Black Panther Party members who were watching the police. The bill removed a law that allowed people to carry loaded firearms in public.

Ten-Point Program

The Black Panther Party first shared its "What We Want Now!" Ten-Point program on May 15, 1967. This was after the Sacramento protest, in the second issue of The Black Panther newspaper.

- We want freedom. We want power to determine the destiny of our Black Community.

- We want full employment for our people.

- We want an end to the robbery by the Capitalists of our Black Community.

- We want decent housing, fit for shelter of human beings.

- We want education for our people that exposes the true nature of this decadent American society. We want education that teaches us our true history and our role in present-day society.

- We want all Black men to be exempt from military service.

- We want an immediate end to POLICE BRUTALITY and MURDER of Black people.

- We want freedom for all Black men held in federal, state, county and city prisons and jails.

- We want all Black people when brought to trial to be tried in court by a jury of their peer group or people from their Black Communities, as defined by the Constitution of the United States.

- We want land, bread, housing, education, clothing, justice and peace.

FBI Actions and Growth (1967-1968)

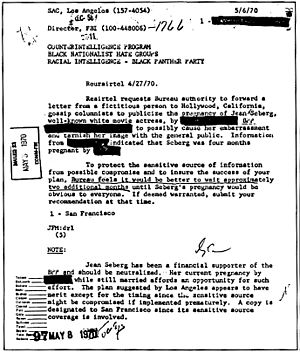

COINTELPRO

In August 1967, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) started a program called "COINTELPRO." Its goal was to "weaken" black nationalist groups and other groups that disagreed with the government. In September 1968, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover said the Black Panthers were "the greatest threat to the internal security of the country." By 1969, the Black Panthers became a main target for COINTELPRO. The program wanted to stop militant black nationalist groups from uniting. It also aimed to weaken their leaders and make them look bad to reduce their support.

COINTELPRO also tried to break up the Black Panther Party by targeting their social programs. This included their Free Breakfast for Children program. The success of this program showed that the government was not doing enough to help children who were poor or hungry. The FBI said the Party's efforts were a way to teach children their ideas. They said this because the Party taught and provided for children better than the government did.

"Free Huey!" Campaign

Huey Newton said he was wrongly accused of a crime. This led to the Party's "Free Huey!" campaign. His conviction made the party even more known among radical groups in America. It also helped the Party grow across the country. Newton was released after three years when his conviction was overturned.

While Newton waited for his trial, the "Free Huey" campaign made friends with many students and anti-war activists. They spread the idea that the problems faced by anti-war protesters were linked to the problems faced by black people. The "Free Huey" campaign attracted many Black Power groups and other activist groups. For example, the Black Panther Party worked with the Peace and Freedom Party. This party wanted to promote strong anti-war and anti-racist ideas. The Black Panther Party helped the Peace and Freedom Party's racial politics seem more real. In return, they received important support for the "Free Huey" campaign.

Growth and Ideology Shift

By 1968, the Party had spread to many U.S. cities. Membership reached about 5,000 by 1969. Their newspaper, The Black Panther, sold 250,000 copies. The group created a Ten-Point Program. This document asked for "Land, Bread, Housing, Education, Clothing, Justice and Peace." It also asked for black men to be excused from military service, among other things. With this program, the Black Panther Party showed its economic and political complaints.

By late 1968, the Black Panther Party's ideas had changed. They moved from focusing only on black nationalism to becoming a "revolutionary internationalist movement." This meant they stopped attacking white people as a whole. Instead, they started to look at society based on class. They focused more on the ideas of Marxism–Leninism and Maoism. Every Party member had to study Mao Tse-tung's "Little Red Book." This was to learn more about people's struggles and how revolutions happen.

Panther slogans and symbols became well-known. At the 1968 Summer Olympics, American medalists Tommie Smith and John Carlos gave the Black Power salute. The Olympic Committee banned them from future games. Film star Jane Fonda publicly supported Huey Newton and the Black Panthers in the early 1970s. She even informally adopted the daughter of two Black Panther members. Fonda and other celebrities got involved in the Panthers' programs. The Panthers attracted many left-wing activists.

The BPP started a "Serve the People" program. This began with a free breakfast program for children. By the end of 1968, the BPP had 38 groups and branches. They claimed more than five thousand members. Eldridge and Kathleen Cleaver left the country before Cleaver had to go to jail. They settled in Algeria. By the end of the year, party membership was around 2,000.

Survival Programs

Inspired by Mao Zedong's advice, Newton told the Panthers to "serve the people." He said "survival programs" should be a top priority. Their most famous program was the Free Breakfast for Children Program. It first ran out of a church in Oakland.

The Free Breakfast For Children program was very important. It was a place to teach young people about the problems facing the Black community. It also taught them about what the Party was doing to help. While children ate, Party members taught them about the Party's ideas and Black history. Through this program, the Party could influence young minds. It also strengthened their ties to communities and gained wide support for their ideas. The breakfast program became so popular that the Panthers Party said they fed twenty thousand children in the 1968–69 school year.

Other survival programs offered free services. These included clothing, classes on politics and money, free medical clinics, and lessons on self-defense and first aid. They also provided transportation to prisons for family members of inmates. They had an emergency ambulance program and tested for sickle-cell disease. The free medical clinics were very important. They showed how the world could work with free medical care. These clinics were involved in community-based health care.

Political Activities

In 1968, BPP Minister of Information Eldridge Cleaver ran for president. He ran on the Peace and Freedom Party ticket. The Black Panthers also greatly influenced the White Panther Party. This group was tied to the band MC5 and their manager John Sinclair. The White Panther Party also had a ten-point program.

Education and International Connections (1969-1970)

Black Panther Party Liberation Schools

The Black Panther Party (BPP) strongly believed in educating people. They thought education was needed for individuals to make community change happen. As part of their Ten-Point Program, they asked for fair education for all black people. Point number 5 said: "We want education for our people that exposes the true nature of this decadent American society. We want education that teaches us our true history and our role in present-day society." To make this happen, the Black Panther Party took charge of their youth's education. They first started after-school programs. Then, they opened Liberation Schools in many places across the country. These schools focused on Black history, writing skills, and political science.

Intercommunal Youth Institute The first Liberation School was opened by the Richmond Black Panthers in July 1969. It served brunch and snacks to students. Another school opened in Mt. Vernon, New York, in July 1970. These schools were informal, like after-school or summer programs. The first full-time and longest-running Liberation school opened in January 1971 in Oakland. This was because of the unfair conditions in the Oakland Unified School District. This district was one of the lowest-scoring in California.

This school was called the Intercommunal Youth Institute (IYI). It was led by Brenda Bay, and later by Ericka Huggins. It had 28 students in its first year, mostly children of Black Panther parents. This number grew to 50 by the 1973–1974 school year. To fully support Black Panther parents who spent their time organizing, some students and teachers lived together all year. The school was different from regular schools. For example, students were grouped by how well they learned, not by age. Students often got one-on-one help because there was one teacher for every ten students.

The Panthers opened Liberation Schools to give students an education that public schools were not providing. Public schools often focused on European culture and paid little attention to black history and culture. Students at the Liberation Schools took regular classes like English, Math, and Science. But they also learned about class structure and racism in systems. The main goal was to teach students to think about revolution. Students also got to do community service projects. They practiced writing by sending letters to political prisoners linked to the Black Panther Party. The school received money from Black Panther fundraising and community support.

Oakland Community School In 1974, more people wanted to join the school. So, officials moved it to a bigger building and changed its name to Oakland Community School. That year, the school had its first graduating class. The number of students kept growing, from 50 to 150 between 1974 and 1977. But the school kept its main idea of teaching each student individually. In September 1977, the school received a special award from Governor Edmund Brown Jr. and the California Legislature. It was honored for "having set the standard for the highest level of elementary education in the state."

The school closed in 1982. This was due to government pressure on party leaders. There were not enough members or money to keep the school running.

International Ties

People from many countries supported the Panthers. In countries like Norway and Finland, activists organized a tour for Bobby Seale and Masai Hewitt in 1969. The Panthers talked about their goals and the "Free Huey!" campaign. Seale and Hewitt also visited Germany, gaining support for the campaign.

Later Years and End (1970-1982)

International Travels

In 1970, a group of Panthers traveled through Asia. They were welcomed by the governments of North Vietnam, North Korea, and China. Their first stop was North Korea. There, the Panthers met with officials to discuss how they could help each other fight against American power. Eldridge Cleaver went to Pyongyang twice. After these trips, he worked to share the writings of North Korean leader Kim Il-sung in the United States. After North Korea, the group went to North Vietnam with the same goal: to end American power. Eldridge Cleaver was invited to speak to Black American soldiers by the North Vietnamese government. He told them to join the Black Liberation Struggle. He argued that the U.S. government was only using them. Cleaver believed black soldiers should fight for their own freedom instead of risking their lives for a country that treated them unfairly. After leaving Vietnam, Cleaver met with the Chinese ambassador to Algeria. They shared their dislike for the American government.

When Algeria held its first Pan-African Cultural Festival, they invited many important people from the United States. Among them were Bobby Seale and Eldridge Cleaver. The festival allowed Black Panthers to connect with leaders of different international movements against imperialism. This was an important time. It led to the creation of the International Section of the Party. At this festival, Cleaver met with the ambassador of North Korea. This ambassador later invited him to a conference in Pyongyang. Eldridge also met with Yasser Arafat and gave a speech supporting the Palestinians.

Party Split

Important disagreements among the Party's leaders led to a split. Some members felt the Black Panthers should take part in local government and social services. Others wanted to keep fighting the police. These disagreements caused the split. In January 1971, Newton removed Geronimo Pratt from the party. Newton also removed two of the New York 21 members and his own secretary, Connie Matthews, who then left the country.

Some Panther leaders, like Huey P. Newton and David Hilliard, wanted to focus on community service and self-defense. Others, like Eldridge Cleaver, wanted a more direct and forceful approach. In February 1971, Eldridge Cleaver made the split worse. He publicly said the Party was becoming too focused on small changes instead of big revolution. He called for Hilliard to be removed. Cleaver was expelled from the main committee. He then led a separate group called the Black Liberation Army. This group had been a secret military part of the Party before. From mid to late 1971, hundreds of members across the country left the Black Panther Party.

Delegation to China

In late September 1971, Huey P. Newton led a group to China for 10 days. At every airport in China, thousands of people greeted Huey. They waved copies of the Little Red Book and held signs. These signs said things like "we support the Black Panther Party, down with US imperialism." During the trip, the Chinese arranged for him to meet and have dinner with ambassadors from North Korea and Tanzania. He also met with groups from North Vietnam and South Vietnam. Huey thought he would meet Mao Zedong. Instead, he had two meetings with the first Premier of China, Zhou Enlai. One of these meetings also included Mao Zedong's wife. Huey described China as "a free and liberated territory with a socialist government."

Focus on Oakland and Decline

In early 1972, the party started closing many of its groups and branches across the country. Members and operations were moved to Oakland. The political part of the southern California group was shut down, and its members moved to Oakland. The hidden military part stayed for a while. The remaining parts of the L.A. group later became the Crips, a street gang.

The party made a five-year plan to take over the city of Oakland politically. They put almost all their money and effort into winning political power in the Oakland city government. Bobby Seale ran for mayor, Elaine Brown ran for city council, and other Panthers ran for smaller offices. Neither Seale nor Brown were elected. Many Party members left after these losses. However, a few Panthers did win spots on local government committees. After the election defeat, Newton removed many top party leaders in early 1974. These included Bobby and John Seale, David and June Hilliard, and Robert Bay. Dozens of other Panthers who were loyal to Seale also left.

In 1974, as Huey Newton prepared to go to Cuba, he made Elaine Brown the first Chairwoman of the Party. Under Brown's leadership, the Party became more involved in local elections. This included Brown's unsuccessful run for Oakland City Council in 1975. Brown also gave women Panthers more important roles in the organization, which had mostly been led by men.

By 1980, the number of Panther members had dropped to 27. The Panther-supported Oakland Community School closed in 1982. This happened during a problem where Newton was accused of misusing money. This marked the official end of the Black Panther Party.

What Happened After and Their Impact

There is much discussion about how the Black Panther Party affected society. Author Jama Lazerow writes that the Panthers became "national heroes in black communities." They did this by combining strong black pride with the tough spirit of young black working-class people. They also mixed this with the energy of new left-wing politics in the Bay Area. In 1966, the Panthers said Oakland's black neighborhoods were their territory. They saw the police as outsiders. The Panther's goal was to defend the community. Their famous "policing the police" action showed how white Americans were often protected from the police brutality that was common in black city areas.

Professor Judson Jeffries calls the Panthers "the most effective black revolutionary organization in the 20th century." The Los Angeles Times called the organization a "serious political and cultural force." They also called it "a movement of intelligent, explosive dreamers." The Black Panther Party is shown in exhibits and lessons at the National Civil Rights Museum.

Many former Panthers have held elected office in the United States. These include Charles Barron (New York City Council), Nelson Malloy (Winston-Salem City Council), and Bobby Rush (US House of Representatives). Most of them praise the BPP's help in black liberation and American democracy. In 1990, the Chicago City Council created "Fred Hampton Day" to honor the slain leader. In Winston-Salem in 2012, many local officials and community leaders put up a historic marker for the local BPP headquarters. State Representative Earline Parmone said, "Because they had courage, today I stand as ... the first African American ever to represent Forsyth County in the state Senate."

In October 2006, the Black Panther Party held a 40-year reunion in Oakland.

Since the 1990s, former Panther chief of staff David Hilliard has offered tours in Oakland. These tours visit places important to the Black Panther Party's history.

Groups Inspired by the Black Panthers

Various groups have taken names inspired by the Black Panthers:

- Assata's Daughters, a black activist group in Chicago, was started in 2015. It is named after Black Panther Assata Shakur. The group has goals similar to the Black Panthers' 10-Point Program.

- Gray Panthers often refers to groups that speak up for the rights of older people.

- Polynesian Panthers, a group that supports Māori and Pacific Islander people in New Zealand.

- Black Panthers, a protest group that fights for social fairness and the rights of Mizrahi Jews in Israel.

- White Panthers, refers to the White Panther Party, an anti-racist American political party from the 1970s.

- The Pink Panthers, refers to two LGBT rights groups.

- Dalit Panthers, an Indian social reform group that fights against unfair treatment based on social class in India.

- The British Black Panther movement, which grew in London in the late 1960s and early 1970s. It was not officially linked to the American group, but it fought for many of the same rights.

- The French Black Dragons, a black group against fascism.

- The Young Lords

- Huey P. Newton Gun Club, named after the Black Panther Party's founder.

- Memphis Black Autonomy Federation

In April 1977, Panthers strongly supported the 504 Sit-Ins. The longest of these was a 25-day occupation of the San Francisco Federal Building by over 120 people with disabilities. Panthers provided daily home-cooked meals to support the protest. This protest eventually led to the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) thirteen years later.

New Black Panther Party

In 1989, a "New Black Panther Party" was formed in Dallas, Texas. Ten years later, this group became home to many former Nation of Islam members. This happened when Khalid Abdul Muhammad became its leader.

Groups like the Anti-Defamation League and the Southern Poverty Law Center say the New Black Panthers are a black separatist group that promotes hate. The Huey Newton Foundation, former chairman and co-founder Bobby Seale, and members of the original Black Panther Party have said that this New Black Panther Party is not real. They have strongly disagreed with it, stating that there "is no new Black Panther Party."

|

See also

In Spanish: Partido Pantera Negra para niños

In Spanish: Partido Pantera Negra para niños