Buenaventura River (legend) facts for kids

The Buenaventura River was a river that people once believed existed. It was thought to flow from the Rocky Mountains all the way to the Pacific Ocean. This imagined river would have crossed the Great Basin area in what is now the western United States.

For many years, people dreamed of finding a "Great River of the West." This river would be like the Mississippi River but on the western side of North America. The hope was to find a water path from one side of the continent to the other. This would make travel and trade much easier, avoiding the long and dangerous trip around Cape Horn at the tip of South America.

Contents

Early Explorers: Dominguez, Vélez de Escalante, and Miera

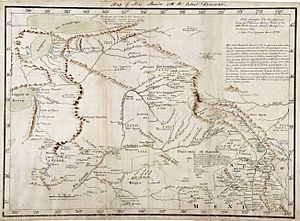

In 1776, two Franciscan missionaries, Atanasio Domínguez and Silvestre Vélez de Escalante, set out on an important journey. They wanted to find a land route between Santa Fe in Nuevo México and Monterey in Alta California. This trip is now known as the Domínguez–Escalante expedition. Ten men were part of the group, including Bernardo de Miera y Pacheco (Miera), who drew maps for the expedition.

On September 13, they found a river in modern-day Utah. This river was the Green River, which flows south into the Colorado River. They named it San Buenaventura after a Catholic saint.

At first, the Buenaventura River was a real river, just with a different name. Dominguez and Vélez de Escalante wrote in their journal that the river flowed west above where they crossed it. It then flowed southwest near them and continued southwest. They also noted that after joining another river, the Buenaventura turned south. So, the original Buenaventura River is real and is known today as the Green River.

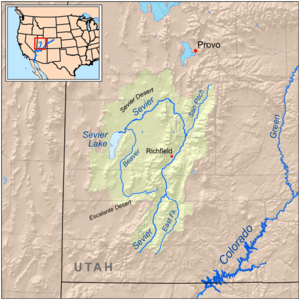

The expedition later met some Ute Native Americans near what they called Lake Timpanogos. The explorers then turned south-southwest. On September 29, they were surprised to find another river, the Sevier River. This river flowed from the south-southeast and then turned west. The explorers noted that the Native American name for this river suggested it was the same Buenaventura River. However, they doubted this because it was much smaller downstream than upstream, which is unusual for a river. They named this new river the Rio San Ysabel. The Native Americans told them it flowed west into a lake (Sevier Lake) and beyond.

Even though Dominguez and Vélez de Escalante had doubts, Miera's maps showed something different. His maps did not include the Rio San Ysabel. Instead, they showed the Buenaventura River flowing southwest from where they found it in Utah, all the way to the Sevier Lake. Miera even suggested to the king of Spain that a waterway might exist to the Pacific Ocean. This could be through the Buenaventura or the Timpanogos River, which Miera's map showed flowing west from the Great Salt Lake. The Spanish misunderstood the Native Americans' description of the "extremely salty" lake as the ocean. They also thought the river flowing from "Lake Timpanogos" (which is the Jordan River between Utah Lake and the Great Salt Lake) was a path to the Pacific.

This mistake of showing the Buenaventura flowing southwest to a lake was repeated by many early mapmakers. Famous explorers like Alexander von Humboldt and Zebulon Pike used these maps. Aaron Arrowsmith also published a map in 1814 showing the Buenaventura flowing to "Lac Sale" (Salt Lake). These mapmakers did not try to map the areas west of what Dominguez and Escalante had explored.

The Dream of a River to the Pacific

People had long hoped for a river that flowed from the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific Ocean. Such a river would make travel and trade much easier. This dream was like the search for the famous Northwest Passage.

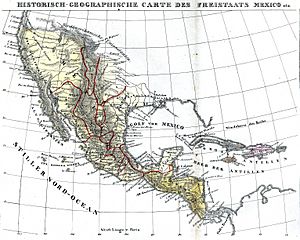

When Francisco Garcés drew maps of Alta California, he did not fully understand the Sierra Nevada mountains. He drew the "San Felipe" or San Joaquin River starting beyond the Sierras and flowing to the Pacific Ocean. Later, other mapmakers extended this "San Felipe" river almost to the Sevier Lake.

In 1820, a map by Sidney Edwards Morse showed the Rio de San Buenaventura flowing into a lake. The western parts of this lake were unknown. This map even suggested a "Supposed river" that might connect the Buenaventura to the Bay of Francisco, possibly linking the Atlantic and Pacific. Another map from 1822 showed the Rio de S. Buenaventura starting near the Colorado River and ending in a salt lake.

Other mapmakers became bolder. They started drawing rivers flowing from Lake Timpanogos and "Lac Salado" (Salt Lake) all the way to the Pacific Ocean. Henry Schenck Tanner's map in 1822 was very influential. It showed the Buenaventura River flowing from the central Rockies, through the Sevier Lake, and into the Pacific Ocean south of Monterey Bay. This map also showed two rivers flowing from Lake Timpanogos (Utah Lake). One went to San Francisco Bay, and the other to Port Orford, Oregon. Similar maps were published by Anthony Finley in 1826 and Thomas Bradford in 1835.

The Great Salt Lake was first seen by white North Americans in 1824. Jim Bridger and Etienne Provost both reported it as very salty. When explorers learned about the Great Salt Lake, they started thinking it was the "Lake Timpanogos" on the maps. They didn't realize that salty lakes like the Great Salt Lake and Sevier Lake usually have no outlets. So, they began trying to find the rivers that supposedly flowed from these lakes west to the Pacific, as maps like Tanner's promised.

In 1825, William Henry Ashley tried to float down the Green (Buenaventura) River. He wanted to see if it flowed into "Salt Lake" (Sevier Lake) or the Colorado River. He started in present-day Wyoming. After passing through dangerous canyons, he stopped his trip before reaching the Colorado River. Even so, he believed the Green River did flow into the Colorado. He then explored the Great Salt Lake overland with Provost. The next spring, his partner, Jedediah Smith, explored areas north and west of the Great Salt Lake. He found no rivers flowing out of it. He sent more men to explore the shoreline, but they also failed to find the imaginary rivers. However, this information took a long time to reach mapmakers. In 1836, Tanner still showed the three rivers on his maps. Because of these maps, when John Bidwell traveled to California in 1841, he was told to bring tools to build canoes. The idea was to sail from the Great Salt Lake to the Pacific.

After Ashley retired, Jedediah Smith focused on finding the Buenaventura. In 1826, he led an expedition south from Idaho. He reached the mouth of the Jordan River at the Great Salt Lake and traveled south along the east side of Utah Lake. He saw the Jordan River as the outlet of Utah Lake, so he didn't explore the lake further. He found the Sevier River flowing northeast. Thinking it continued north to Utah Lake, he didn't believe it was the Buenaventura. He continued southwest to Southern California. In 1827 and 1828, he explored the western side of the Sierra Nevada mountains. He didn't find any river that crossed the range. However, he heard the Sacramento River called the "Buenaventura" by Luis Antonio Argüello. A map by Albert Gallatin (1836), based on Smith's travels, labeled the Sacramento River as the Buenaventura. It also said Lake Timpanogos was the Great Salt Lake, but it didn't connect the two.

In the spring of 1827, Daniel Potts, a fur trader working for Smith, found the Sevier River further downstream. He followed it to the Sevier Lake and confirmed it was a salty lake. But he did not try to go around it to find an outlet. Instead, he followed the entire river upstream to its source.

The question of whether the Buenaventura River existed was a big debate until 1843. That year, John C. Frémont, with scouts like Thomas Fitzpatrick and Kit Carson, led a dangerous expedition. They traveled from the Columbia River to Sacramento, California through the Sierra Nevada. By then, trappers and guides knew that the Buenaventura River did not flow from the Green River's source. But maps still showed it and other rivers flowing from the Great Salt Lake area to the sea.

On January 27, 1844, at the Walker River, Frémont briefly thought he had found the mythical river. But it was a mistake in his measurements. Two days later, he realized his error. He finally proved that the Buenaventura River did not exist. Later, he found the Salinas River flowed into the Pacific at about the same spot where maps showed the Buenaventura's mouth. Frémont believed this was the source of the legend and named the Salinas River "Rio San Buenaventura."

After Frémont proved that no rivers flowed across the Great Basin to the Pacific, President Polk was slow to accept it. But once it was clear that no east-to-west waterway existed in the western United States, Frémont and his father-in-law, Senator Thomas Hart Benton, turned their attention to building a transcontinental railway. This railway was finished in 1869, after the Mexican–American War (1846–48) and the American Civil War.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Río Buenaventura para niños

In Spanish: Río Buenaventura para niños