Comanche history facts for kids

The

The Comanche were a powerful Native American tribe who lived on the Great Plains in what is now the United States. In the 1600s, they moved south from Wyoming. By the 1700s and 1800s, the Comanche became the most important tribe on the southern Great Plains. They were often called the "Lords of the Plains."

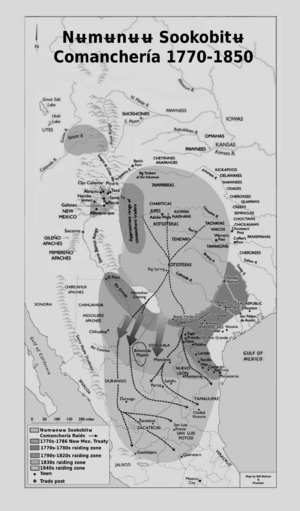

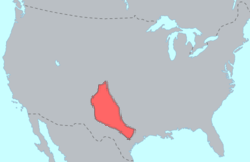

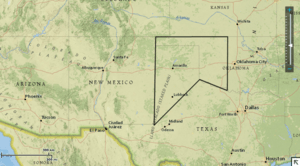

The Comanche controlled a large area known as Comancheria. They shared this land with friendly tribes like the Kiowa, Kiowa-Apache, Wichita, and later the southern Cheyenne and Arapaho. The Comanche became strong and wealthy because of their horses, trading skills, and raiding. They were also good at diplomacy, which helped them stay in charge for over a hundred years. They hunted bison (buffalo) for food and skins.

Even though their large territory was like an empire, the Comanche were not ruled by one single leader. Instead, they were made up of several groups, called bands. These bands spoke the same language but acted on their own. In 1780, when they were most numerous, there were about 20,000 Comanche people.

The Comanche often fought with neighboring tribes, American settlers, and especially the Mexicans. They were known for their fierce fighting and raids. They also took thousands of captives from other Native American tribes, Mexicans, and Americans. These captives often became part of the Comanche way of life. By 1875, many Comanche had died from European diseases and wars. The buffalo, their main food source, were almost gone. The U.S. army defeated the Comanche, and they were forced to live on an Indian reservation in Oklahoma.

In 1920, fewer than 1,500 Comanche were left. Today, over 15,000 people are enrolled as Comanche tribal members. Many of them live in and around Lawton, Oklahoma. Of the three million acres promised to the Comanche and their allies in 1867, only a small part remains in Native American hands today.

Early History of the Comanche

The Comanche people are closely related to the Eastern Shoshone tribe from Wyoming. The Comanche likely separated from the Shoshone in the 1500s. They moved south into Colorado and became bison hunters, living a nomadic life on the Great Plains. This move might have happened because the weather became wetter, which helped the buffalo population grow.

In southern Colorado, the Comanche formed an alliance with the Ute tribe. In the late 1600s, both tribes lived in similar ways. From fall to early spring, the Comanche split into small groups. They were hunter-gatherers in western Colorado, especially in the San Luis Valley. In late spring, the Comanche and Ute crossed the mountains to the Great Plains. There, they hunted buffalo during the summer.

The Comanche probably got their first horses in the 1680s. This happened after the Pueblo people drove the Spanish out of New Mexico for 12 years. Spanish horses then became available to Native American tribes. Having horses allowed the Comanche to travel widely and become skilled nomads.

In 1706, a Spanish soldier named Juan de Ulibarrí first wrote about the Comanche. He heard that the "Ute and Comanche tribe were about to attack" a Pueblo settlement. This attack did not happen, but the Comanche gained a reputation as a strong tribe that raided settled peoples. The Ute word kɨmantsi, meaning 'enemy', is likely where the name "Comanche" came from. The Comanche called themselves nɨmɨnɨɨ, which means 'people'.

Comanche Expansion in the 1700s

In the 1700s, Comanche history can be looked at in three main ways. First, their relationship with the Spanish, Pueblo, Ute, and Apache peoples in New Mexico. Second, their relationship with the Spanish, Apache, and Wichita in Texas. Third, their relationship with the French and other tribes in Oklahoma and Kansas.

By the late 1700s, there were two main groups of Comanche. The western bands lived in New Mexico, Colorado, Kansas, and the Texas panhandle. They focused on the Spanish settlements in New Mexico. The eastern bands lived in southwestern Oklahoma and central Texas. They focused on the Spanish settlements in Texas. Later, new challenges came from American settlers and other tribes moving into Oklahoma.

Comanche and New Mexico

In the early 1700s, the Ute and Comanche became very strong on the northern border of Spanish New Mexico. They mostly stole livestock. In 1716, the governor of New Mexico attacked a peaceful Ute/Comanche camp. Many were killed or captured and enslaved. After this, fighting between the Spanish and Ute/Comanche became more violent. In 1719, the Ute and Comanche raided the Taos area, killing several people. The Spanish tried to find them but failed. They learned that the Apache in southern Colorado were being heavily attacked by the Ute and Comanche.

In the 1720s, the Comanche took control of the Arkansas River valley in Colorado. By the 1730s, they became the first fully horse-mounted, buffalo-hunting nomads on the Great Plains. They pushed the Apache tribes south and west off the Great Plains. The Comanche also grew apart from their Ute allies. By 1749, the Ute asked the Spanish for help against the Comanche. The war between the Ute and Comanche continued for the rest of the 1700s.

The Spanish and Pueblo population in New Mexico was only 15,000 in 1749. The Comanche began to control the colony, sometimes trading and sometimes raiding. Despite some losses, the Comanche remained strong. In 1747, a Spanish and Pueblo force attacked a Comanche and Ute camp, killing 107 and capturing 206. In 1751, Spanish troops trapped 300 Comanche, killing 112 and capturing 33. These defeats led the Comanche to seek peace. The peace agreement of 1752 gave the Comanche good trade rights and treated them as a separate nation. This also allowed them to fight the Ute.

In 1761, after a small disagreement, the Spanish joined the Ute and attacked a Comanche camp. They killed over 400 and captured 300 people. The peace agreement in 1762 was still mostly good for the Comanche. It made them allies, not enemies, of the Spanish in New Mexico.

This peace broke down after 1767. The Comanche started a fierce campaign that killed hundreds of Spanish and Pueblo people. It left the Rio Grande valley in New Mexico in ruins. In 1774, the Spanish fought back. Six hundred soldiers surrounded a Comanche band, killing 300 men, women, and children and taking over 100 prisoners. Being captured by the Spanish often meant being sent to mines or sugar plantations for men, and slavery in Spanish homes for women and children. But the Comanche kept getting stronger in New Mexico.

The last big battle between New Mexican settlers and the Comanche was in 1779. The governor of New Mexico, Juan Bautista de Anza, was a skilled fighter. He led 800 men, including Ute and Apache helpers, north into Comanche land. He killed Cuerno Verde ("Green Horn"), the most important Comanche war leader, and many of his followers. Raids decreased but did not stop completely.

In 1785, De Anza offered peace if the Comanche could agree on one leader. This idea gained strength when the eastern Comanche in Texas signed a peace treaty with the Texas Governor. Among the western Comanche, a leader named White Bull (Toro Blanco) opposed peace. The peace-seeking Comanche killed him. The Kotsoteka, Jupe, and Yamparika bands then gave the power to make peace to a leader named Ecueracapa. After several meetings, De Anza sent a signed treaty to Mexico City in July 1786. He also arranged a truce between the Ute and Comanche. This treaty ended major fighting between the Comanche and the Spanish and Pueblo people of New Mexico.

The peace of 1786 lasted. The Comanche and Spanish worked together against their common Apache enemy. Spanish settlements grew eastward onto the Great Plains. The Spanish gave gifts to the Comanche and allowed them to trade for guns and ammunition. Some Comanche children even went to Spanish schools. Travelers could cross the Plains safely. Traders, called Comancheros, brought Spanish goods into Comanche territory and traded for buffalo robes, meat, and horses.

With a safe place in New Mexico, the Comanche began to raid deep into Mexico. In 1841, the Mexican government ordered the New Mexico Governor to fight the Comanche. But the Governor refused, saying, "To declare war on the Comanches would completely ruin New Mexico."

Comanche and Texas

Like New Mexico, the Spanish colonies in Texas struggled against Apache and Comanche attacks in the 1700s. By the 1770s, there were only about 3,000 Spanish people in Texas.

The first time the Comanche were recorded in Spanish Texas was in 1743. By then, the Comanche had already pushed the Apache off the Great Plains. The Spanish and Lipan Apache had been at war but made peace in 1749 to fight the Comanche. This peace lasted only a few years.

In the 1750s, the Comanche in Texas allied with tribes the Spanish called Norteños (northerners). These included the Wichita, Tonkawa, and Hasinai (Caddo). In 1758, a large group of Norteños, including Comanches, attacked the Mission Santa Cruz de San Sabá. This mission was built by the Spanish to move north from San Antonio. In 1759, a Spanish army tried to get revenge but was defeated by the Taovaya and Comanche in the Battle of the Twin Villages.

At first, the Comanche traded meat and buffalo skins to the farming Wichita tribes for crops like corn. The Wichita also helped trade Comanche horses to Spanish colonies in Louisiana. In the 1770s, this alliance broke down. European diseases weakened the Wichita. The Comanche moved east and began trading directly with the Spanish and French in Louisiana.

Meanwhile, the Spanish in Texas were also threatened by the powerful Osage tribe and Apache raids. They started seeking peace with the Comanche. However, in 1778, a massacre of a Comanche peace group in eastern Texas led to the most serious Comanche attacks on Spanish settlements and other tribes in Texas. The Spanish dream of a strong colony in Texas was crushed by the Comanche attacks.

In 1780-1781, a smallpox epidemic greatly reduced the Native American population, including the Comanche. This epidemic, plus the realization by both Spanish and Comanche that they had other enemies, led to peace talks. In 1785, with the help of the Wichita, a peace agreement was made with the Eastern Comanche. It included large gifts for the Comanche and the return of all Spanish prisoners. This led to a similar agreement between New Mexico and the western Comanche in 1786.

Comanche and the French, Osage, and Pawnee

The French had little direct contact with the Comanche. They traded with other tribes on the eastern edge of the Great Plains, who then traded with the Comanche. The French were interested in trade, unlike the Spanish who wanted to colonize and spread Christianity. In 1720, the Spanish sent an army to remove French traders, but most of the Spanish soldiers were killed by the Pawnee. The first Frenchmen known to meet the Comanche were the Mallet brothers in 1739. The French helped make a peace agreement between the Wichita and the Comanche in 1746.

The most powerful tribe the Comanche faced on the eastern Great Plains was the Osage. The Osage kept the Comanche from moving east beyond central Kansas and Oklahoma. In the 1700s, the Osage expanded from Missouri onto the Great Plains to hunt buffalo and get skins for the French. The Osage had easy access to French goods, including guns. The Osage's hostility forced the Wichita, who were allies of the Comanche, to move south to the Red River Valley around 1750. In northern Kansas and Nebraska, the Comanche sometimes fought with the Pawnee, another strong tribe allied with the French. From the 1740s, the Comanche raided the Pawnee for captives, and the Pawnee raided the Comanche for horses.

Rise and Fall: The 1800s

In 1805, the governor of Louisiana said the Comanche were "the most powerful nation of savages on this continent." The Comanche controlled a huge area of the Great Plains. They had many horses to trade and relied on the endless buffalo herds for food. A smallpox epidemic had reduced their numbers in 1780-1781. More outbreaks of smallpox and other European diseases continued to lower their population. However, their numbers were helped by captives who joined the tribe. In 1822, the Mexican government thought the Comanche had 2,500 captives. In 1790, the Comanche gained new Native American allies: 2,000 Kiowa and Kiowa-Apache joined them.

The peace agreements with the Spanish mostly worked, keeping a balance between cooperation and conflict. The Spanish continued to give gifts to the Comanche. The French left after 1803 when they sold Louisiana to the United States.

American settlers on the borders of Comancheria brought new markets and new dangers. The Spanish were few, but the Americans were many. The Spanish and Pueblo population of New Mexico was 25,000 in 1800 and growing. Texas had about 5,000 Spanish people. In contrast, the United States had 10 million people in 1820, and Americans were starting to settle in Texas. There was a big demand for Comanche horses and mules.

The peace with the Spanish in Texas weakened after 1795. In New Mexico, it suffered when the Mexican War of Independence began in 1810. The new, disorganized country of Mexico had few resources to give the Comanche their usual gifts. In 1822, the Mexicans tried to reduce the Comanche threat by inviting Comanche leaders to Mexico City. They signed a treaty that gave the Comanche many trading rights. In 1824, to help Texas survive, the Mexican government allowed foreign settlers. Americans, who already traded a lot with the Comanche, poured in. The Mexicans were worried. In 1825, 330 Comanche rode into San Antonio, the capital of Texas, and stayed for six days, taking goods and enjoying themselves. In 1832, 500 Comanche occupied San Antonio for several days without resistance. Mexico's weakness in Texas allowed the Americans to win Texas's independence in 1836.

Comanche and Independent Texas: 1836-1845

By 1836, when Texas became independent, the number of American immigrants had erased the Comanche's population advantage. From fewer than 5,000 Spanish in the early 1800s, Texas had 38,000 Spanish and American people in 1836. The Native American population in Texas, including the Comanche, was estimated at 14,000. Also, as the American population grew, the Native Americans suffered more losses from smallpox in the late 1830s.

However, in 1840, the Comanche gained important allies. An agreement with the southern Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes ended a long war on the Comanche's northern border. This brought about 2,000 new allies. The Cheyenne and Arapaho were allowed to live in Comancheria. The Comanche were generous, giving about five horses to each Cheyenne and Arapaho man and woman.

The new Republic of Texas immediately had problems with the Comanche. In May 1836, Comanche and Kiowa warriors killed five men and captured five women and children at Fort Parker. One of the captives was 9-year-old Cynthia Ann Parker. She later married a chief, Peta Nocona, and had a son, Quanah Parker, who would become the last war chief of the Comanche in the 1870s. Comanche society easily welcomed captives because they needed people to help manage their large territory.

The first President of Texas, Sam Houston, tried to make a clear border between the American settlers and Comancheria. His successor, Mirabeau B. Lamar, fought the Comanche directly. In 1840, the Comanche sent a peace group to San Antonio. In a disagreement about captives, Texas soldiers killed 35 Comanche, many of them chiefs, in the Council House Fight. In response, the Comanche, led by Buffalo Hump, launched the Great Raid of 1840. They attacked and looted the towns of Victoria and Linville near the Gulf of Mexico. They killed several people and took many goods. With the help of Tonkawa scouts, Texas militia ambushed the retreating Comanche in the Battle of Plum Creek, killing several Comanche. Later that year, Texas militia attacked a Comanche village and killed 140 people.

Mirabeau's campaigns against the Comanche cost the Texas government a lot of money. Both Texas and the Comanche wanted peace. A treaty between Texas and the Texas Comanches was approved in December 1845. It set up trading posts that acted as a border. The Comanche agreed not to raid in Texas in exchange for gifts and trading rights.

Raiding Mexico: 1779-1870

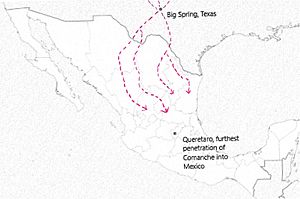

After 1840, Comanche actions in Texas became more about defense. Instead, the Comanche focused on raiding Mexico, south of the U.S. border. The Comanche raided south of the Rio Grande as early as 1779, targeting the Lipan Apache. In the 1820s, the newly independent and weak Mexican state could not protect its northern areas. It also could not give the Comanche the yearly payments they were used to. In 1826, the government of Nuevo León forbade its citizens in the northern parts of the state from traveling alone. They had to be in groups of at least 30 armed men.

Large-scale Comanche raids began in 1840 and continued until 1870. The Comanche and their allies, the Kiowa and other tribes, raided hundreds of miles south of the border. They killed thousands of people and stole hundreds of thousands of livestock. Much of this livestock was sold to Americans in the United States. In 1848, a traveler said that "the whole country from New Mexico to the borders of Durango is almost entirely depopulated." Farms and ranches were abandoned, and people stayed in towns and cities.

The northern states of Mexico and their soldiers were left to deal with the Comanche raids on their own. The Mexican national government was too weak from financial problems and civil war to help the north.

Comanche and the United States: 1845-1875

When the United States took over Texas in 1845, it made a new treaty with the Comanches and other Texas tribes in May 1846. This treaty promised peace, trading posts, a visit by Comanche leaders to Washington, D.C., and a payment of $18,000 in goods. A border between Comancheria and Texas was mentioned but not clearly drawn.

The Comanche leaders went east and met President James K. Polk. But with the Mexican–American War just starting, Congress was busy. The Senate did not approve the treaty. By the time the treaty was changed and approved in March 1847, the Comanches felt betrayed. War was avoided only because traders and Indian agents gave credit to send some of the promised gifts. When the changes were read to the Comanches, the meeting almost ended, but they finally agreed. More money was set aside for gifts, but a border was still never clearly set.

There was also a big question about who was in charge of dealing with the Texas tribes: the federal government or the state government. This problem was not solved until after the American Civil War. In the meantime, both made policies, which caused confusion. So, the 1846 peace treaty brought little peace to Texas.

In May 1847, Texas allowed German settlers to make their own treaty with the Texas Comanches. In exchange for land, the Germans promised a trading post and gifts. But the Germans went beyond the agreed border and were slow to pay. In response, the Comanches raided. A border was eventually set by the Texas governor, but it was to be enforced by the American army. The army felt they could not enforce state laws. Meanwhile, Texas continued to use its ranger companies, which were not under federal control. The Rangers did not stop people from moving onto Comanche lands but would fight back if new settlements were attacked. To make things worse, only the Penateka band had signed the 1846 treaty. Other Comanche bands did not feel bound by it and continued to raid in Texas.

On the other side of Comancheria, many things changed with the start of the Mexican War in 1846. An American army took Santa Fé and moved to California. The Santa Fé Trail became a very busy military supply route. Forts were built to protect it. American soldiers were sent to these posts and often fought with Plains Indians.

The first part of 1848 was calm. Texas Comanches even helped survey the route for a new trail across southern Texas to California. But the calm ended suddenly with the California Gold Rush. Thousands of gold-seekers needed horses, and the Comanches met this new demand. Horse raids increased in Texas, but the main target was northern Mexico. Comanche raids went deep into Mexico, reaching their peak in 1852. To protect the routes across the plains, the United States held a "Peace on the Plains" conference at Fort Laramie in 1851. This tried to stop fighting between tribes by setting borders for their lands.

Almost every plains tribe attended and signed the 1851 Fort Laramie Treaty. The Comanches and Kiowa did not attend. A smallpox epidemic had hit their villages, and they did not trust the northern tribes. Since the Santa Fé Trail was important, an agreement with them was needed. In 1853, the Kiowa and Yamparika Comanche signed their own treaty at Fort Atkinson. In return for safe travel and a promise to stop raiding in Mexico, the United States agreed to pay these tribes $18,000 per year for ten years.

The Comanches and Kiowa had been angry in 1852 for several reasons. They had been hit hard by smallpox and cholera epidemics. The first smallpox epidemic (1780–81) was so bad that some Comanche groups disappeared. Smallpox hit again in 1816–17. The wave of people from the California Gold Rush brought smallpox (1848) and then cholera (1849) to the Great Plains. These diseases were terrible for all plains tribes, especially the Comanches and Kiowa. The government estimated the Comanche population dropped from 20,000 in 1849 to 12,000 by 1851. They never fully recovered. Smallpox struck again in 1862, and cholera returned in 1867. By 1870, there were fewer than 8,000 Comanches, and their numbers were still falling fast.

The Comanches kept their promise for safe travel on the Santa Fe Trail. But they remained angry about events in Texas. White settlers kept moving deeper into Comancheria, and the Texas Rangers kept attacking them. As the frontier moved forward, the American army built new lines of forts. At first, these forts had mostly foot soldiers, so the Comanche could just go around them. But within a few years, the foot soldiers were replaced by new cavalry units. It took three lines of forts and most of the army's strength before the Civil War to control the Comanches in Texas.

Even more frustrating for the Comanches were posts like Fort Stockton. These were meant to block the "Great Comanche War Trail" leading to northern Mexico. The Americans were required by a treaty to prevent raids into Mexico. Between 1848 and 1853, Mexico filed 366 complaints about Comanche and Apache raids coming from north of the border.

Not all efforts to deal with the Texas Comanches were military. In 1854, Texas set aside land for the United States to create three reservations on the upper Brazos River for Texas tribes. Some Penateka Comanche were convinced to move there. But local settlers quickly accused the reservation tribes of stealing horses. Many of these claims were false or about raids by Comanches from the Staked Plains. The situation became dangerous in 1858 after the army left Camp Cooper.

Texas urged the army to fight Comanches outside its borders. Texas Rangers found that Kiowa and Comanche groups used Oklahoma as a safe place to raid Texas and escape. Between 1858 and 1860, the army's new cavalry units attacked Comanches in Oklahoma. In May 1858, Texas Rangers attacked a Comanche village. In October 1858, Captain Earl Van Dorn attacked a Comanche village, killing 83. The next May, Van Dorn attacked Comanches in Kansas.

These attacks caused problems elsewhere. Attacked from Texas, Comanches and Kiowa split into small groups and moved north near the Santa Fe Trail. In response to more Indian attacks on the trail in 1860, three cavalry groups were sent to punish them. In July, one group fought a battle with Kiowa, Cheyenne, Arapaho, and possibly some Comanches.

In spring 1859, a group of 250 settlers attacked the reservation but were pushed back. The Indian agent, Robert Neighbors, hated by local Texans, arranged to close the reservations. He moved the residents to Indian Territory. The peaceful Penateka Comanche were forced to leave Texas, along with tribes like the Tonkawa, who had helped the Texas Rangers. After leaving his people at the new Wichita agency, Neighbors was ambushed and shot on his way home to Texas.

When federal soldiers left the region during the Civil War, Confederate troops took their place. A Confederate agent signed two treaties with Comanches in August 1861. The Comanches were promised many goods and services. But because the Confederacy needed money for the war, the Comanches never received what was promised. Most federal forts that had kept the Comanche in check were abandoned. With the border unguarded and promises broken, Comanches began raids to push back settlements. The Texas frontier moved back over 100 miles during the Civil War. Northern Mexico was hit by a new wave of Comanche raids.

The war also gave the Comanches a chance to get revenge on the Tonkawa. The Comanche disliked the Tonkawa for helping the Texas Rangers. Texas Comanches especially hated the Tonkawa because they had killed and eaten the brother of one of their chiefs. The Comanches found cannibalism disgusting.

After Texas Indian agents took over the Wichita Agency in Oklahoma, Comanches took part in an attack on the agency in October 1862. When it was over, 300 Tonkawa had been killed. The survivors moved to Texas. In later years, they would get their revenge by serving as army scouts against the Comanches.

After 1861, Comanches, Kiowa, Cheyenne, and Arapaho almost managed to close the Santa Fé Trail. Federal officials learned the Comanches had signed treaties with the Confederacy and believed they had become hostile. During the Civil War, Union army ranks on the frontier were filled with men who hated Native Americans. By late 1863, these soldiers' actions had led to an alliance between the Lakota, Cheyenne, Arapaho, Kiowa, Comanches, and Kiowa-Apache.

In autumn 1864, Colonel Kit Carson led soldiers from New Mexico into the Staked Plains to punish the Comanches and Kiowa. His scouts found their camps on November 24. Carson found more Comanches and Kiowa than he could handle. The First Battle of Adobe Walls was almost "Carson's Last Stand." Only the clever use of artillery kept the Yamparika and Kiowa from overwhelming his position. Afterwards, Carson returned to New Mexico.

In the final days of the Civil War, the Confederacy tried one last time to use the anger of the plains tribes. In May 1865, a meeting was held in western Oklahoma. Many Comanches and other tribes attended. But Robert E. Lee had surrendered in Virginia two weeks earlier, ending any hope for the Confederacy.

That summer, the plains were in chaos. The Santa Fé and Overland trails were closed. Almost every plains tribe was at war with the United States. As federal troops returned to their posts, government officials met with the plains tribes in October to make peace. The Little Arkansas Treaty of 1865 gave the Comanches and Kiowa western Oklahoma and the entire Texas Panhandle. It also promised payments of $15 per person for forty years.

Only some Comanche groups signed the agreement. The Kwahada and Kotsoteka did not. When the payments arrived, there was disappointment. The Comanches expected guns and good quality goods. Instead, they got rotten Civil War rations and cheap blankets. The peace was soon broken by both sides, and war continued for two more years. It was a harsh fight. General William Tecumseh Sherman ordered the army not to pay ransom for white captives.

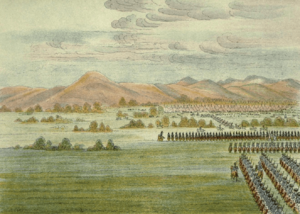

While the army planned to use force, the government decided to try one last treaty. This led to a big peace conference at Medicine Lodge Creek in Kansas in October 1867. In exchange for gifts and yearly payments, the Comanches and Kiowa signed the Medicine Lodge Treaty. They gave up Comancheria for a 3 million-acre reservation in southwestern Oklahoma. This plan did not work as intended. Because of a cholera outbreak, the Kwahada did not attend or sign the treaty. They did not feel bound by it and chose to stay on the Staked Plains.

Most other Comanches moved near Fort Cobb and stayed on the reservation for the winter. But since the treaty was not yet approved, there was no money for food. After a winter of starvation, most Comanches and Kiowa left the reservation in summer 1868. They raided Texas and Kansas again, using the new reservation as a safe place to avoid the army. Even Fort Dodge was attacked. The frustrated Indian agent resigned.

The treaty was approved in July, and money became available. But the army was put in charge of giving out the payments. All tribes were told to report to Fort Cobb or be considered hostile. General Philip Sheridan planned a winter campaign against the hostile tribes. In November, soldiers attacked a Cheyenne village. In December, another attack hit a Comanche village. Afterwards, most Comanches and other tribes returned to the agencies.

In March 1869, the Comanche-Kiowa agency moved to Fort Sill. Only the Kwahada were still on the Staked Plains. The Kiowa and other Comanches were on the reservation. But by late 1869, small war parties sometimes left to raid Texas. In May 1871, during one of these raids, the Kiowa almost killed William Tecumseh Sherman, the commanding general of the U.S. army. Sherman was furious. He ordered the arrest of Kiowa chiefs who were bragging about the raid. They were sent to Texas for trial and sentenced to life in prison. The Comanches and Kiowa launched revenge raids that killed over 20 Texans in 1872. At the same time, Texans stole 1,900 horses from the tribes at Fort Sill.

Meanwhile, the army in Texas tried to stop raids from the reservation and huge thefts of Texas cattle by the Kwahada. These cattle were sold to New Mexico Comancheros. In October 1871, a raid led by Quanah Parker stole seventy horses from the army. Colonel Ranald S. Mackenzie chased the Kwahada for the next two years. The campaign ended with an attack on a Comanche village in September 1872. Mackenzie captured 130 women and children and held them hostage. This slowed the raiding while the Comanches negotiated for their release. In April 1873, they were released. In October, the Kiowa chiefs were released from prison after serving only two years, on the condition that the raiding stop.

Buffalo Hunting

At the same time, the massive killing of plains buffalo began. Between 1865 and 1875, the number of buffalo on the Great Plains dropped from fifteen million to less than one million. Army commanders unofficially allowed this by giving free ammunition to hunters. This destroyed the way of life for the plains tribes. In the winter of 1873–74, Cheyenne hunters reported that Kansas buffalo hunters were destroying the southern buffalo herds. As this news spread, violence broke out at the Darlington and Wichita agencies. Large groups of Cheyenne left the reservation for the plains. At first, the Comanches and Kiowa thought the Cheyenne were wrong, but their story of dead buffalo was confirmed.

Second Battle of Adobe Walls

In December, the government decided to deal harshly with the Kiowa and Comanches to end the raids in Texas. The agent at Fort Sill was ordered to limit food and stop giving out ammunition. Panic set in, and by May, several Comanche and Kiowa groups had left the reservation. They decided to attack the buffalo hunters on the Staked Plains. In June 1874, a large Comanche-Cheyenne war party attacked twenty-three buffalo hunters at Adobe Walls. The Second Battle of Adobe Walls started the Buffalo War (or Red River War) (1874–75), the last major Indian war on the southern plains. After the first attack failed, the Comanches faced fire from the hunters' long-range buffalo guns and had to retreat. The uprising spread as more warriors left the agencies and joined the hostile groups. To stop this, soldiers began to disarm the Comanches and Kiowa who had stayed at the agencies.

By September, only 500 Kiowa and Comanche were still on the reservation. The others were on the Staked Plains. That same month, the army began to move. Three groups of soldiers moved into the heart of the Staked Plains. Trapped between them, the Comanches, Kiowa, and Cheyenne had little rest. Colonel Nelson A. Miles' group made the first contact and defeated some Cheyenne. For the Comanches, Cheyenne, and Kiowa, the biggest blow happened when Mackenzie found a mixed camp hidden in Palo Duro Canyon in September. After driving off the warriors, he burned the camp and killed 2,000 captured horses.

There were few other battles, but the constant pressure and pursuit throughout the fall and winter had an effect. Starving, the remaining Comanches, Kiowa, and Cheyenne began to return to the agencies, mostly on foot because they had eaten their horses. By December, there were 900 on the Fort Sill reservation. In April, 200 Kwahada, who had never given up, surrendered at Fort Sill. In June, the last 400 Kwahada, including Isatai'i and Quanah Parker, surrendered. The war was over. Mackenzie sold many of the Comanche and Kiowa horses. He used the money to buy sheep and goats for his former enemies.

By 1879, the buffalo were gone. That year, the Kiowa-Comanche and Wichita agencies were combined. The Comanches adapted, but in their own way. Quanah Parker, using his Texas background, became an important Comanche leader. He collected fees from cattle herds that crossed the reservation and sold grazing rights to nearby Texas ranchers. Few argued with him about prices. With his five wives, he moved into a large, comfortable house called the "Star House." It had eight large stars painted on the roof, to show he had more stars than any U.S. army general. He was elected a sheriff and served as a tribal judge. By the time he rode in Theodore Roosevelt's parade in 1905, Quanah had many horses, cattle, and cultivated farmland.

|

| Leon Lynch |

| Milton P. Webster |

| Ferdinand Smith |