Dale Abbey (ruin) facts for kids

Inside view of the east window, Dale Abbey, Derbyshire.

|

|

| Monastery information | |

|---|---|

| Full name | Church of the blessed Mary of Stanley Park - Ecclesia beatae Mariae de Parco Stanleye |

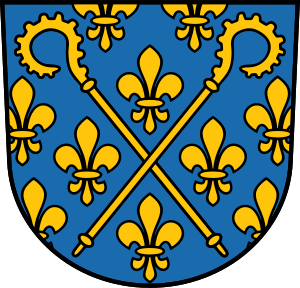

| Order | Premonstratensian |

| Established | 15 August 1204 (probably consecration of the church) |

| Disestablished | 24 October 1538 |

| Mother house | Newsham Abbey |

| Dedicated to | Mary, mother of Jesus |

| Diocese | Diocese of Coventry and Lichfield |

| Controlled churches |

|

| People | |

| Founder(s) |

|

| Site | |

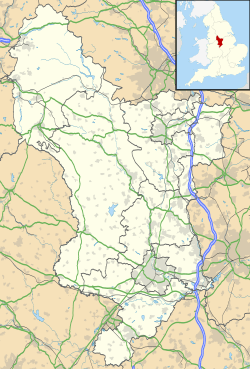

| Location | Dale Abbey, near Ilkeston, Borough of Erewash, Derbyshire, DE7 4PN |

| Coordinates | 52°56′39″N 1°21′01″W / 52.9443°N 1.3502°W |

| Visible remains | Arch of church east window, wall footings. |

|

Listed Building – Grade I

|

|

| Official name: Abbey Ruins | |

| Designated: | 10 November 1967 |

| Reference #: | 1140435 |

|

Listed Building – Grade I

|

|

| Official name: Church of All Saints and Vergers Farmhouse | |

| Designated: | 10 November 1967 |

| Reference #: | 1140436 |

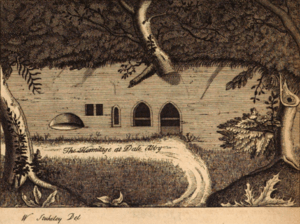

| Official name: Hermitage 170m south east of All Saints Church | |

| Designated: | 12 April 1972 |

| Reference #: | 1019632 |

| Public access | East window visible from nearby footpath. Permission to vew footings and museum: contact Abbey House. Church still in use: contact parish office for visiting details. Hermitage open at all times. |

Dale Abbey, also known as the Abbey of Stanley Park, was a religious house near Ilkeston in Derbyshire, England. Today, you can find its ruins in the village of Dale Abbey, which is named after it. The abbey's story began with a hermitage (a quiet place for a religious person to live alone) in the early 12th century. After a few attempts, it officially became an abbey in 1204.

The abbey belonged to the Premonstratensians, also called Norbertines or White Canons. This was an order of canons regular (priests who live in a community under a religious rule). Dale Abbey grew to own many small properties, especially in the East Midlands. It also developed a network of granges (farm estates run by the monks) and took control of several churches. Over time, its strictness and reputation changed, especially in the 15th century. By 1536, its income was too low to avoid being closed down by the king. Even though there were some serious accusations, the abbey was allowed to pay a fine to keep going until 1538, when it was finally closed.

Contents

How Dale Abbey Started

The official start of Dale Abbey, from the Premonstratensian point of view, was in 1204. It was founded from Newsham Abbey in Lincolnshire. However, a special book called the abbey's chronicle (a historical record) tells a much longer story about how it began. This chronicle was written in the mid-13th century by a man named Thomas de Muskham. He wanted everyone to know his name, so he hid it in the first letters of different parts of the story!

The Baker Who Became a Hermit

The chronicle says the first part of the story came from Matilda de Salicosa Mara. She was a local landowner and was seen as a founder of the community at Dale. Matilda told the story to Thomas Muskham when he was a canon (a type of priest) at Dale.

Her story begins with a baker from Derby. This baker was very kind and used his money to buy food and clothes for the poor. He would take these gifts to his church to be given out. One autumn afternoon, the Blessed Virgin Mary appeared to him in a dream. She told him to "go to Depedale and there you will serve my son and myself in a solitary life." She promised him a wonderful afterlife if he did this.

The baker kept his dream a secret. He gave away everything he owned and set off eastward. He didn't know where Depedale was, so he listened to people talking. As he passed through Stanley, he heard a woman tell her daughter to take calves to Deepdale. The baker took this as a sign from God. He asked the woman for directions and soon arrived at his destination.

The place was described as "a marshy place, extremely frightening, and far from human habitation." Deepdale was about 2.5 kilometers (1.5 miles) southeast of Stanley. It was a wet, grassy area with the Sow Brook flowing through it. The baker found a hillside and dug out a small rock house. He then settled down to live a simple, religious life there.

The local landowner, Ralph Fitz Geremund, noticed smoke from the hermit's new home. He thought someone was illegally clearing land. But when he investigated, he was so impressed by the hermit's simple life that he gave him a share of the profits from his mill. This was important because the mill's profits were still valuable to Dale Abbey much later.

The rest of the hermit's story came from an old canon named Humfrid. The hermit faced many spiritual struggles in his later years. To find peace and water, he looked for a new home. He built a small hut and a chapel by a spring in the valley below. He dedicated this chapel to God and the Blessed Mary. He lived there serving God until he died.

A Vision of Future Glory

Thomas Muskham then tells another story about a man named Uthlagus. This man was near Deepdale because it was on a common route between Nottingham and Derby. Uthlagus means "outlaw," so he was likely a highway robber. One summer day, he fell asleep on a hill and had a dream.

In his dream, he saw a golden cross where the abbey church would later stand. The top of the cross touched the sky, and its arms reached to the ends of the earth. The whole world shone brightly from its light. He also saw people from many different nations coming to worship this cross.

When he woke up, Uthlagus told his companions about his dream. He said that the valley below was a holy place and that God was there. He believed that future generations would tell stories of the great things God would do in that valley. He said the valley would be "white with the flowers of virtues" and full of happiness. People from different nations would come to worship God there forever.

After sharing his dream, Uthlagus left his group. He was never seen again, but people rumored he became a hermit at Deepdale. These stories show how the abbey's beginnings were seen as special and even miraculous.

Early Attempts to Build the Abbey

The story of Dale Abbey's early days is full of attempts to build a religious community. Members of local noble families tried to set up a religious house at Deepdale. While there are no exact dates, the chronicle gives clues about when these events happened in the 12th century.

The Grendon Family's Role

Serlo de Grendon was an important figure in these early attempts. He married Margery, the daughter of Ralph de Geremund, who had helped the first hermit. Serlo received part of Ockbrook as Margery's dowry (property a bride brings to her marriage).

Serlo was very close to his aunt, who was also his godmother. She became known as the Gomme (godmother) of the Dale. Serlo gave her the land at Deepdale for her lifetime. She built a house there and made her son, Richard, the chaplain (a priest who serves a private chapel). This chapel was probably on the site of the hermit's old prayer place.

Augustinian Canons Try and Fail

At the Gomme's request, Serlo de Grendon gave Deepdale to the Augustinians from Calke Priory. Richard the chaplain joined their order. A group of six Augustinian canons came to Deepdale. They built a church, which cost a lot of money.

One of the canons, Humfrid, traveled to Rome. He managed to get special rights for the priory, like being able to bury people and being protected from interdict (a church punishment). However, the canons started to lose their discipline and began hunting in the nearby forest. The king found out and made them leave because they were a threat to his game. Humfrid went back to being a hermit, and the others returned to Calke. This Augustinian community at Deepdale lasted from about 1149 to 1158.

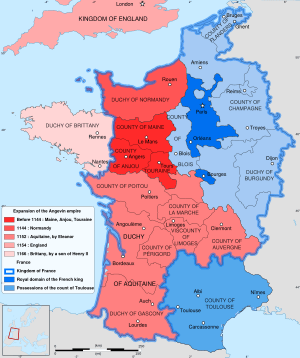

More Attempts by Premonstratensians

Next, a group of six canons from Tupholme Abbey in Lincolnshire tried to settle at Deepdale. Tupholme was a "daughter house" of Newsham Abbey, the first Premonstratensian house in England. The canons from Tupholme were given Stanley Park. They even built a mill there. But they found there wasn't enough good farmland to support them. After seven years, they were called back to Tupholme. Before they left, they cut down the oak trees in the park to sell for money.

Another attempt was made by William de Grendon, Serlo's son. He brought five Premonstratensian canons from Welbeck Abbey in Nottinghamshire. This was around 1194-1196. These canons also struggled with poverty. They even had an accident where all their lamps fell down during a service. The abbot of Welbeck visited them and saw they didn't even have enough food or drink. So, he called them back to Welbeck.

The Abbey is Finally Established

The successful founding of Dale Abbey happened almost by chance. During these failed attempts, William FitzRalph, Margery's brother, was an important person in the region. He was the sheriff of Nottingham and Derby from 1168 to 1180.

William was buying properties for his daughter Matilda, who had married Geoffrey de Salicosa. Geoffrey and Matilda, who had been married for seven years without children, asked William to give Stanley to the Premonstratensians. They wanted to found a religious house in Stanley Park. William talked to his nephew, William de Grendon, and invited him to donate the Grendons' site at Deepdale. The Deepdale site was added later, as the main problem with previous attempts there had been poverty.

So, Stanley Park was given to the Premonstratensians for the new community. This is why it was called the Abbey of Stanley Park for a long time. William de Grendon then donated the Deepdale site, along with some rents, to the Stanley Park church of St Mary. He did this for the good of his own soul and his brother's. He also wanted a daily gift of bread and beer to be given to the poor at the new abbey.

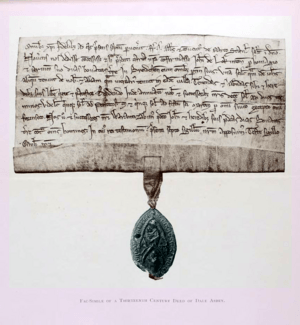

A definite date for the founding at Stanley is April 1, 1196. Later, in 1331, the abbey showed a charter from King Richard I from that date. It gave the Premonstratensian Abbey of Stanley "all the liberties and free rights which the other abbeys of the Premonstratensian Order have in England."

William FitzRalph left his daughter and her husband to sort out the details. They met with Abbot Lambert of Newsham Abbey and got nine canons to start a community at Deepdale. The official date for the abbey's foundation is August 15, 1204, which is the Feast of the Assumption. This date probably marks the opening or blessing of the new abbey church.

Abbey Lands and Supporters

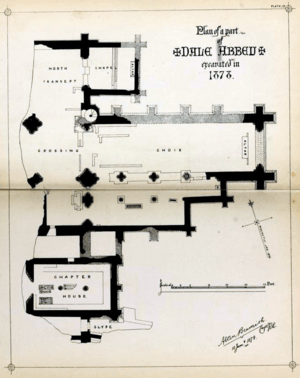

The Cartulary of Dale Abbey is a large book with records of all the land and gifts given to the abbey over many centuries. It has about 530 copies of deeds (legal documents). Most of these are from the 13th century.

Founding Families and Their Gifts

In the early days, valuable gifts kept coming from the families of William FitzRalph and Serlo de Grendon. The family tree below shows how they were related.

| Family tree of founders and related benefactors | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

William de Grendon, who supported the abbey, gave land from his family's estates at Ockbrook. He also wanted to be buried there, along with his brother Bertram, who became a canon at Dale Abbey.

Geoffrey de Salicosa and Matilda also gave many gifts to Dale Abbey. Geoffrey gave all his lands in Sandiacre. Matilda gave her manor (a large estate) of Alvaston, with meadows and pastures. She also gave half of a mill at Borrowash. It seems they left all their lands in Nottinghamshire to the abbey. They were rewarded for their generosity by having two sons and two daughters.

The families of William and Matilda continued to support the abbey. Their children and other relatives made many more donations, especially in areas like Alvaston and Stanton by Dale. The de Muskham family, to which the chronicler Thomas likely belonged, also gave many lands to the abbey.

Growing the Abbey's Lands

Most of the gifts to Dale Abbey were small plots of land. These lands were often mixed in with properties owned by other people. The abbey often had to defend its lands in court. However, the abbey also used its extra money to buy land, especially from landowners who were in debt.

For example, at Stanley, many local farmers and craftsmen gave small pieces of land to the abbey. The very first donor mentioned was Walter Laundri, a stonemason. He gave five acres and a small plot of land. Some donations were even smaller, like half an acre given for a burial. The abbey's expansion around Stanley led to a disagreement with the Earl of Derby. In 1229, a survey was ordered to mark the boundary with the earl's estates.

The abbey also acquired land by helping people pay off their debts, especially to Jewish lenders. In the 13th century, Jewish lenders were a main source of credit for landowners. Monasteries like Dale Abbey would pay off these debts. In return, the landowners would give their land to the abbey, or agree to pay rent to the abbey for it. This was a way for the abbey to expand its holdings at a good price. The original landowners were freed from their debts, and the abbey gained more land.

Later Land Acquisitions

In the 14th century, it became harder and more expensive for religious houses to acquire land due to new laws called the Statutes of Mortmain. These laws required special permission from the king. For example, in 1323, King Edward II gave Dale Abbey permission to acquire land worth up to £5. But the abbey had to pay for this permission, and there was an expensive investigation to see if it would harm royal interests. It took almost 20 years to complete this group of acquisitions.

Later, in 1363, King Edward III allowed the abbey to acquire land worth up to £20 a year. In return, the canons had to mention him daily in their prayers and meetings. However, the abbey often ended up paying for the right to acquire more land than they actually managed to get. The kings would often count the value of the land as higher than it actually was.

Churches Controlled by the Abbey

The abbey also gained control over several churches. This meant they could choose the priest for that church and often received the tithes (a portion of income, usually 10%, paid to the church).

The abbey acquired the right to choose the priest for Egginton church early on. However, they later lost half of this right. In 1345, the Bishop of Coventry and Lichfield gave the abbey the tithes from half of the church, perhaps as a way to make up for the loss.

Kirk Hallam church was another early acquisition. Richard of Sandiacre gave the abbey the right to choose the priest, along with some land. By 1298, the abbey had taken full control of the church. This meant the main tithes went to the abbey, and the church became a vicarage (a church where the priest is paid a salary by the abbey).

The church at nearby Stanton by Dale might have been built entirely by Dale Abbey. So, the abbey always owned the right to choose the priest and received all the tithes. Dale Abbey also received half the right to choose the priest for Trowell church in the mid-13th century.

In 1337, Nicholas de Cantilupe gave the abbey the right to choose the priest for Greasley church in Nottinghamshire. He also gave them rents. In return, the canons of Dale had to set up a special service for Nicholas and his family in Ilkeston church.

Later, in 1385, King Richard II allowed Dale Abbey to take control of Ilkeston church. The actual donor was William la Zouche, a noble who had inherited the church. He wanted special prayers and masses at Dale Abbey for himself and his family. However, the abbey only held Ilkeston church for less than ten years. In 1394, Pope Boniface IX appointed a new priest, which went against the abbey's rights. This led to legal problems and even the priest being put in prison for a time.

The church at Heanor was transferred to Dale Abbey later, during the reign of Edward IV. The right to choose the priest was held by Henry Grey, a powerful local noble. In 1475, the king allowed the transfer. But in return, the abbot of Dale had to give the king some land near Nottingham. The king wanted this land for a new hunting park near Nottingham Castle. The agreement also said the abbey had to pay for a permanent priest and give money to the local poor.

| Location of church | Name/Dedication | Dates | Donor | Approximate coordinates |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Egginton | St Wilfrid | Half the rectory appropriated 1345. | Roger Northburgh | 52°50′51″N 1°36′15″W / 52.8475°N 1.6042°W |

| Kirk Hallam | All Saints | Advowson acquired early 13th century. Appropriated by 1298. | Richard of Sandiacre | 52°57′37″N 1°19′08″W / 52.9604°N 1.3189°W |

| Stanton by Dale | St Michael and All Angels | Probably founded by Dale Abbey during the 13th century. | 52°56′19″N 1°18′36″W / 52.9386°N 1.31°W | |

| Trowell | St Helen | Half of advowson acquired mid-13th century. | William de Trowell | 52°57′10″N 1°16′53″W / 52.9528°N 1.2815°W |

| Greasley | St Mary | Advowson acquired under a licence of 11 March 1337. | Nicholas de Cantilupe | 53°01′11″N 1°16′19″W / 53.0197°N 1.2719°W |

| Ilkeston | St Mary | Licence of 12 July 1385 provided for transfer of advowson and appropriation. | William la Zouche, 3rd Baron Zouche | 52°58′15″N 1°18′33″W / 52.9707°N 1.3091°W |

| Heanor | St Lawrence | Licence issued 10 February 1475 permitted transfer of advowson and appropriation. | Henry Grey, 4th Baron Grey of Codnor | 53°00′49″N 1°21′06″W / 53.0135°N 1.3518°W |

Abbey Economy

The lands given to Dale Abbey allowed it to set up several granges. These were farming centers directly managed by the abbey.

List of Granges

The table below lists the granges that belonged to Dale Abbey.

| Name/location of grange | Notes | Approximate coordinates |

|---|---|---|

| Stanley grange | This grange was key to the abbey's founding. Many early land gifts were at Stanley. Excavations in 1997 found eight iron smelting furnaces here, used between 1220 and 1315. Abbot John Stanley retired here in 1491. | 52°57′38″N 1°22′04″W / 52.9606°N 1.3679°W |

| Boyah grange | Serlo de Grendon I gave all his land at Boyah to the canons around 1160. The first mention of it as a grange was between 1289 and 1298. | 52°56′18″N 1°20′30″W / 52.9383°N 1.3418°W |

| Ockbrook or Littlehay Grange | This grange is mentioned during the abbey's closing, with rye, barley, peas, and hay in its barns. It was later called Little Hall Grange. | 52°55′49″N 1°21′31″W / 52.9304°N 1.3587°W |

| Ambaston Grange | Dale Abbey had lands scattered around Alvaston. The ′′Taxatio′′ (a tax record) confirms Dale had a grange in Alvaston, and Ambaston was likely it. | 52°52′56″N 1°21′22″W / 52.8823°N 1.3561°W |

| Gosewonge or Bathley Grange | The abbey had many small landholdings in Bathley and nearby areas. This grange likely dates from the 13th century. | 53°07′24″N 0°50′13″W / 53.1233°N 0.8370°W |

| Griffe Grange | Griffe was listed among the abbey's lands in a charter from Edward I in 1294. Today, Griffe Grange is a place name on maps. | 53°06′14″N 1°37′28″W / 53.1040°N 1.6244°W |

| Southome Grange | The exact location of this grange is unknown, but it was in Dale Abbey village. It was one of the properties given to Francis Pole in 1540. | Position unknown. Presumed at the southern end of Dale village. 52°56′38″N 1°21′04″W / 52.9438°N 1.3512°W |

Mills and Their Importance

Watermills were a very important part of the abbey's economy. They were strongly protected when threatened. The mill built at Stanley by the second priory continued for centuries. It was known as Parke Mill and later Baldock Mill. Records from 1291 show two mills at Stanley.

Richard of Sandiacre gave the abbey a mill at Kirk Hallam. The abbey also had a share of a mill at Bathley. Mills provided many benefits: tenants had to use the mill, paying a fee for grinding their grain. Villagers also provided labor to maintain the mills and their ponds. The ponds also offered valuable fishing rights, which could feed the canons or provide income.

Abbot Simon built nine new mills on the River Derwent at Borrowash. This led to legal problems with Sir Thomas Bardulph. In 1269, Sir Thomas gave up his rights to the mills for a payment of 45 marks.

The Borrowash mills also caused problems with the merchants of Derby. They complained in 1276 that the abbot's weirs (dams) at Borrowash were blocking the river. This made it impossible for ships to trade at Derby. In 1283, there was even violence. A military order called the Order of Saint Lazarus attacked one of the abbey's mills. Abbot Laurence, along with over a hundred armed men, fought back. The king ordered an investigation, but the result is unknown.

Abbots of Dale

The abbots of Dale Abbey were important figures. They had a big impact on the Premonstratensian order in England and were also significant political leaders.

How Abbots Were Chosen

There is only one detailed record of an abbot's election at Dale. Since Newsham Abbey was Dale Abbey's "mother house," elections were overseen by Newsham's abbot and his deputies. In 1332, an election was held at Dale. The current abbot, John of Horsley, had resigned. His replacement, John Woodhouse, had resigned after only 15 weeks.

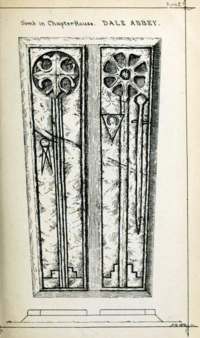

After a special Mass, the abbots from Newsham and the canons of Dale went to the chapter house (a meeting room). A warning was read that anyone who was excommunicated (kicked out of the church) should leave. Then, five canons were chosen to pick the new abbot. They could choose from among themselves, other canons, or any other Premonstratensian house.

They chose William of Horsley. He was described as "a provident man, and as one most circumspect in things spiritual and temporal." The canons then sang a special hymn and led William to the abbey church. There, he was officially installed as abbot. Back in the chapter house, he received the abbot's seal, and all the canons promised to obey him.

Abbots' Roles in the Order

Dale's abbots had an important role within the Premonstratensian order. They were subject to visits and corrections from the abbot of their mother house, Newsham. However, abbots of Dale were sometimes asked to help other abbots. For example, in 1450, Abbot John Spondon of Dale helped supervise an election at Welbeck Abbey.

Dale's abbots also represented their abbey at important meetings of the order in England and even in France. They sometimes served on special committees that did the main work of these meetings.

Some abbots of Dale had an even wider impact. Abbot William, who served at Dale for two and a half years, was elected head of the entire order in 1233. He was known as a strict reformer. He tried to change things too quickly and was forced to retire.

Abbot John of Horsley was very active in the English Premonstratensian order. Around 1309, he was asked to help with a problem at Egglestone Abbey. The canons there were refusing to support their retired abbot. John tried to find a solution, but it was a long and difficult process.

John of Horsley also became involved in a conflict between the head of the order in France and King Edward II. The king had forbidden English abbeys from sending money overseas. John was one of the leading English abbots who had to deal with this difficult situation.

William of Horsley, likely a relative of John, also represented Dale well. In 1336, as the Hundred Years' War was beginning, he was chosen to lead the Premonstratensian houses in the Midlands. He had to excuse himself from attending a general meeting in France because of the war and the king's orders. In 1344, William was given the right to visit and inspect all Premonstratensian houses in England. This made him effectively the head of the order's deputies in England.

Abbots in Politics

Abbots were important feudal lords and the main link between the abbey and the king. They were also major landowners, involved in local and regional politics.

In 1264, King Henry III took the abbot of Dale under his protection. However, a powerful local rebel, Robert de Ferrers, also claimed to protect the abbey. It's unclear if the abbey had to pay for his protection.

As the English Parliament grew in importance, abbots were often summoned to attend. This was because the king needed more money. Abbots of Dale were summoned to Parliament many times by Edward I and Edward II. Their actual attendance is not always certain.

Kings sometimes asked abbots to do tasks for them. Abbot William de Boney, for example, was twice asked to investigate and reform a corrupt hospital in Derby. Abbots also helped with legal investigations after someone died.

Their status and wealth also drew abbots into local politics. In 1381, Abbot William de Boney complained that Thomas Foljambe and other armed men had attacked him in Derby. Foljambe was a lawyer and part of a powerful family. The case involved important judges and political figures, showing how connected the abbot was. The case eventually faded, but it showed Foljambe's ability to use violence.

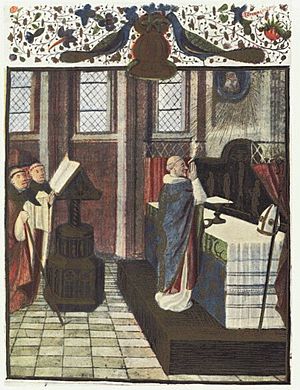

Canons of Dale Abbey

Numbers and Backgrounds

In 1345, Dale Abbey had 24 canons (priests living in the community). In the late 15th century, their numbers were well recorded. In 1475, there were 15 canons plus the abbot. The number stayed around 13-16 canons until 1500. In 1500, there were 16 canons, but four were novices (new members in training). Low numbers were sometimes blamed on the plague. Fifteen canons signed the surrender document when the abbey closed in 1538.

Historians have found over a hundred names of canons and some lay brothers. Many of their last names show they came from nearby towns and villages in the East Midlands. For example, names like Stanley, Stanton, Ilkeston, Derby, and Nottingham were common. There were also names from Lincolnshire, where other Premonstratensian houses were located. The canons seem to have been mostly English-born.

Roles and Daily Life

Premonstratensian canons followed the Rule of St. Augustine, which guided their daily life. This rule was short and focused on daily prayers, study, and moderate work. Canons were usually required to travel and eat in pairs or larger groups.

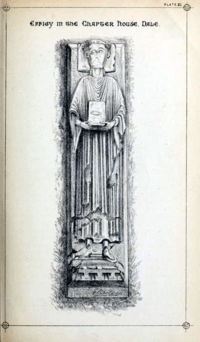

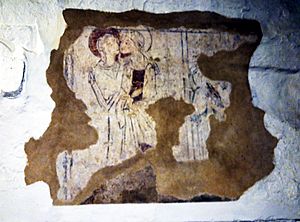

The Premonstratensians were influenced by the Cistercians in how they organized their lives. Their prayer life had a strong focus on Mary, the mother of Jesus. Key events in her life and death were very important to them. The abbey itself was founded on the Feast of the Assumption (August 15), a major celebration for Mary. A 13th-century wall painting in All Saints' Church shows the Visitation, when Mary met her cousin Elizabeth.

Unlike monks, Premonstratensian canons usually became priests. This allowed them to lead services at their own church or other churches the abbey controlled. Visitation records often called them sacerdotes (doers of the holy). Some canons served as vicars or chaplains in nearby parish churches like Ilkeston, Heanor, Kirk Hallam, and Stanton by Dale. These duties sometimes meant they lived away from the abbey.

The main work of all priests was to celebrate the Eucharist (Mass). This was done not just for regular church services, but also for special prayers called chantries. These chantries were for the souls of people who had given land or money to the abbey, including the royal family. Donors, from wealthy founders to humble farmers, expected prayers and masses for their souls and their loved ones.

The responsibilities at Dale Abbey varied. In 1488, Abbot John Stanley had a prior and a subprior to help him. He also had a private chaplain. Besides the parish priests, there was a cantor (who led singing), a cellarer (who managed supplies), and a sacristan (who cared for the church and its items). Sometimes, new members called novices were also given roles like under-sacristan. The position of sacristan was often seen as good training for canons who were not yet priests.

Decline and Closing

The Last Abbot

In 1500, a church inspection found nothing wrong at Dale Abbey. The inspector noted that the number of canons was low due to the plague, but he believed it would recover. After Abbot Richard Nottingham died in 1510, the identity of the abbot becomes less clear. Records sometimes name him John, or John Stanton, and later John Bebe. It's possible it was the same person, John Bebe of Stanton, who served as abbot from 1510 until the abbey closed in 1538.

The Abbey's Final Years

In 1535, an official survey called the Valor Ecclesiasticus was done at Dale Abbey. It found the abbey's income was £144 12 shillings. This amount was below the £200 threshold set by King Henry VIII for smaller monasteries to continue. This meant Dale Abbey was expected to be closed down.

In 1536, two royal officials, Thomas Legh and Richard Layton, visited many monasteries, including Dale. They were looking for bad behavior and false religious practices. Their report, called the "Black Book," made some accusations against the abbot and a canon. It also mentioned that the abbey had relics (holy objects) like a piece of Mary's girdle and milk, and a silver wheel of Saint Catherine. These relics are not mentioned anywhere else. It's possible the accusations were old or even made up.

A Short Delay

Even though its income was low, Dale Abbey was allowed to continue for a short time. On January 30, 1537, it was one of 33 smaller monasteries permitted to stay open. Dale Abbey paid a large fine of £166 13s. 4d. for this exemption, which was more than its annual income. It's interesting that none of the canons asked to leave or transfer to other houses. This suggests they all wanted the community to continue. However, by 1538, even large monasteries were being closed by the king.

The Abbey is Closed

Dale Abbey and all its lands were officially surrendered to the Crown on October 24, 1538. William Cavendish, the king's commissioner, handled the closing. He brought masons and carpenters to remove the roofs of the buildings. This made them unusable.

The surrender document was signed by Abbot John Bebe and 16 other canons. Some of them signed with marks, meaning they couldn't write. The abbot and canons were each given money when they left. The abbot received a large sum of £6 13s. 4d. The other canons received smaller amounts.

On the day of the surrender, a group of local people helped the commissioners make a list of everything in the abbey. This included valuable church items, like two organs, and reusable materials like lead roofing and glass. They also listed items in the kitchen, brewery, and bakery, as well as feather beds. There were large stores of food and livestock at the abbey and its granges. The total value of these items was £77 12s 2d.

The monastic buildings themselves, with their valuable roofing and paving, were not sold. The roofs were taken apart, often by simply knocking out the main stones, causing them to collapse. The six bells of the abbey were also unsold.

Later, a list of pensions for the former canons was made. The abbot received the largest pension, £26 13s. 4d. Other canons received smaller amounts. One canon, Roger Page, did not get a pension because he chose to continue his work as the vicar of Kirk Hallam.

There were some questions about whether the commissioners, Cavendish and Legh, were honest during the dissolution. It was claimed that Cavendish added sums of money to the records without anyone else knowing. However, the investigation didn't stop Cavendish's career.

After the Abbey Closed

The Former Canons

The former canons and abbot continued to receive their pensions, some for many years. In 1552, a commission was set up to check on these pensions. This was because some people were buying and selling pensions as investments.

The report from this commission showed that many of the former canons' pensions were delayed. For example, former prior Richard Wheatley said that ex-abbot John Bebe had died in 1540. Other canons had also died in the years after the abbey closed. Some canons did not appear before the commission. Those who were interviewed in 1552 were still alive in 1555-1556, but after that, their fate is unknown.

The Abbey's Lands After Closing

The abbey's lands were taken over by Francis Pole of Radbourne, Derbyshire on October 23, 1538. Records from 1540 mention the granges of Ockbrook and South-house, a coal mine, a water mill, and a tannery.

Pole later bought the land from the Crown in 1544 for £489 0s. 10d. He then sold most of the Derbyshire estates to his uncle, John Porte. Porte left his vast estates to his three daughters. These daughters and their husbands later sold parts of the manor of Dale to each other.

Over time, through marriages, inheritances, and purchases, the manor of Dale was reunited in 1778 in the hands of Philip Stanhope, 2nd Earl Stanhope. Although the Stanhope family now owned the site and a large estate, most of the original lands bought by Francis Pole had been sold off to many different landowners.

The Lay Bishop

Since Premonstratensian abbeys were independent of the local bishop, their abbots had some church authority in their own parish. When the abbey closed, the lay (non-religious) owner of the manor inherited these powers. This person was called the "lay bishop."

The lay bishop handled church matters like marriage licenses and proving wills through a special court called a Peculiar Court. In the 17th century, many couples chose to marry at Dale because the fees were low. The parish clerk could even lead the ceremony if the minister wasn't available. These fees helped the poor in the village. Later laws changed this, requiring an Anglican minister for marriages. The Peculiar Court continued to handle local will matters until 1857.

The Earls Stanhope took their role as lay bishops seriously. Philip Henry Stanhope, 4th Earl Stanhope, for example, had his status as lay bishop mentioned on his memorial tablet in All Saints' Church. A special "lay bishop's throne" from his time is also in the church.

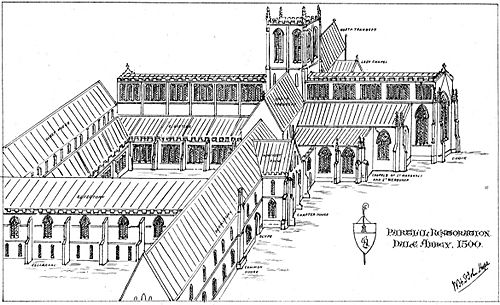

The Abbey Buildings Today

The abbey buildings were intentionally ruined after the closing. The roofs were removed to make them uninhabitable. Dale Abbey was also used as a quarry for new buildings. Sir Henry Sacheverell, the steward, moved parts of the cloister (a covered walkway) to Morley church. Sir Henry Willoughby used a lot of stone from Dale to build a wall around Risley Hall. People found old mason's marks from the abbey on local buildings, showing the stone was reused.

Some houses in Dale still have stone from the abbey. For example, the ground floor of Friar House is built of dressed stone. Abbey House has a large section of abbey masonry, including a chimney and fireplaces, thought to be from the abbey kitchen.

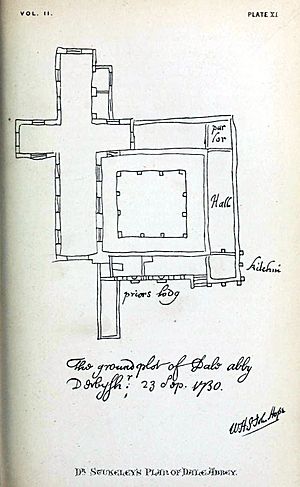

In the early 1700s, much of the abbey was still standing. Drawings from that time show the great east window, the south wall of the nave, and parts of the cloister. In 1730, William Stukeley found the kitchen, hall, abbot's parlor, and gatehouse in good condition. He even made a rough plan of the surviving buildings.

However, the abbey's decay happened very quickly in the mid-1700s. A painting from the 1780s by Joseph Wright of Derby shows that the east window was the most striking feature. By 1789, almost nothing remained except the tall arch of the east window. Today, the abbey looks much as it did then: mostly reduced to its east window and a few other traces, like the kitchen chimney at Abbey House. Only the footings (foundations) show its former size. There was a local belief that if the arch collapsed, the village would have to pay tithes again.

Images for kids

| Claudette Colvin |

| Myrlie Evers-Williams |

| Alberta Odell Jones |