Economy of South Carolina facts for kids

|

|

| Statistics | |

|---|---|

| GDP | $292.9 billion (2022) |

|

GDP growth

|

5.9% (2022) |

|

GDP per capita

|

$48,401 (2022) |

|

Population below poverty line

|

13.8% (2020) |

| Unemployment | 4.2% (November 2020) |

The economy of South Carolina is a big part of the United States economy. In 2022, it was the 25th largest state economy. The biggest industry in South Carolina is tourism. This includes popular places like Myrtle Beach, Charleston, and Hilton Head Island. Another very important part of the state's economy is advanced manufacturing. You can find these factories mostly in the Upstate and the Lowcountry areas.

For most of its history, South Carolina's economy was based on farming. This changed quickly in the 1950s when more factories were built. Before the American Civil War, the state's economy relied almost completely on growing cotton and rice. This work was done by enslaved African people. By the time of the American Revolution, selling rice to Europe made the Lowcountry the richest area in North America. However, South Carolina's economic power started to go down after 1819. This was when cotton farming grew in other parts of the South.

The high profits from cotton made the state rely even more on slavery. Plantation owners invested in more land and enslaved workers. This stopped the economy from becoming more diverse. To try and keep slavery, South Carolina was the first state to leave the Union after Abraham Lincoln was elected. The American Civil War that followed freed enslaved people. But it also caused a lot of damage and ruined the state's economy.

By 1922, South Carolina could no longer depend on growing rice and cotton. This was due to natural disasters and a bug called the boll weevil. Like many other states, South Carolina got help from World War II defense contracts. Also, New Deal building projects during President Franklin D. Roosevelt's time helped the state industrialize. Starting in the 1960s, South Carolina was one of the first states to ask for money from foreign companies. This helped the state move away from farming and the textile industry.

Contents

South Carolina's Early Economy

Colonial Times

Like most early American colonies, South Carolina traded a lot with the West Indies. English settlers first came to the area for crops like tobacco and sugar cane. By 1660, settlers aimed to send timber and food to people in Barbados. The colonists, who grew to 4,000 by 1690, traded with Barbados for "slaves, sugar, and European goods."

By the 1690s, South Carolina started growing rice. Rice became as important to South Carolina as tobacco was to Virginia. The demand for rice kept growing. By 1740, rice made up almost 60 percent of all exports from the southern colonies. It was also nearly 10 percent of all goods shipped from British America.

In the early 1700s, South Carolina's economy was quite varied and wealthy. Settlers sent rice and naval stores (like tar and pitch for ships) to Great Britain. They traded with Native American tribes for deer skins and enslaved people. They also continued trading with the West Indies. During this time, Charleston was the fourth largest city in North America.

But rice farming changed South Carolina into a "rice-only" economy. This led to a huge demand for enslaved workers. Large farms with many enslaved people replaced smaller, mixed farms. This created more wealth, but also a bigger gap between rich and poor. It also led to more trade with Great Britain and less with the Caribbean. It's thought that between 1700 and 1775, about 40 percent of all Africans brought to the United States came through Charleston's harbor.

The rice plantations in the lowcountry made it the wealthiest area on the continent. South Carolina benefited from its ties to the British Empire. However, British rules to control the colonies and fears of slave uprisings led South Carolinians to declare independence.

Slavery and the Economy

The use of enslaved people from Africa was central to South Carolina's economy before the Civil War. The need for enslaved workers first grew in the 1790s. This was because of a short tobacco boom, new settlements in the state's backcountry, and more demand for cotton.

After a rumored slave rebellion led by Denmark Vesey in 1822, attitudes toward slavery changed. South Carolinians saw it as a "positive good" rather than just a necessary evil. By the 1830s, South Carolina was the only state where most white citizens owned enslaved people.

Charleston's once active intellectual life began to fade. The state's thinkers spent their time defending slavery instead of writing about other topics. Owning enslaved people also became a sign of respect and status.

Historians explain that slavery was important because of property rights. Owning enslaved Black workers allowed owners to use labor in places white workers would not go. It also allowed owners to move to new land better for growing cotton. For most white slave owners in South Carolina, the value of their enslaved people increased over time. This constant rise in value made slavery even more deeply rooted in the state.

Important Farm Crops

Tobacco

Tobacco was a major crop in South Carolina during three main periods. It was first planted near Charles Town in the 1670s. It was important for 20 years before the lowcountry switched to rice. Tobacco came back in the 1780s in the state's backcountry. This second period peaked in 1799, when South Carolina exported about ten million pounds of tobacco. The last big period of tobacco farming started in the Pee Dee region in the 1880s.

The second tobacco boom led to big improvements in roads and canals. After South Carolina produced 2.6 million pounds of tobacco in 1783, Governor William Moultrie called for new laws. These laws led to better roads, bridges, and canals to help transport the tobacco.

The tobacco farming in the Pee Dee region was the largest and most important. By 1880, this area was very poor. Land prices had dropped by half, and farming was in a bad state after the Civil War. But, new types of bright leaf tobacco for cigarettes greatly increased demand. Farmers started planting it again. In 1880, South Carolina grew very little tobacco. But from 1890 to 1899, its tobacco production jumped from 200,000 pounds a year to 20 million. This tobacco boom brought more trade, banking, and higher land prices. It also made railroad companies extend their lines into the region.

Cotton

Indigo was once a main crop in South Carolina. But it became unprofitable after the Revolutionary War. It was slowly replaced in the lowcountry sea islands by sea cotton. This special, long-fiber cotton could only be grown in South Carolina. It became the main crop for a century and tied the region even more to slavery. By the early 1800s, sea cotton, mostly sent to Britain, made up 20% of the country's cotton exports.

From 1800 to 1820, new farming methods improved the quality and amount of cotton. Cotton grown in the upcountry had times of too much production. But the high-quality sea cotton had its own market and was not affected by this.

Cotton farming was only profitable near the coast until the 1790s. Then, demand for cotton grew because of new machines in Britain and the Haitian Revolution. This led to growing short-fiber cotton in the upcountry. This type of cotton was not as good as sea cotton. However, it could be grown easily in the Savannah River Valley. It used similar farming methods as tobacco, which was the region's first cash crop. By 1811, 30 million pounds of short-fiber cotton were exported from the state. By 1860, that number had doubled to 60 million.

Cotton prices went up and down throughout the 1800s. After an economic downturn in 1819, the upcountry of South Carolina faced a depression for most of the 1820s. The state never got back its economic power compared to other states. Good times returned from 1833 to 1836. But the Panic of 1837 hit the cotton market hard. It did not recover until the late 1840s.

After Mississippi and Alabama became the main cotton areas, South Carolina's upcountry produced only 5% of the nation's cotton. The economic problems of the 1840s caused many people to leave the upcountry. This also led to a movement to diversify the economy. During the transportation boom of the 1850s, the cotton market became strong again. More banks opened, and towns grew. As more profit was made from cotton, and its farming wore out the soil, the idea of diversifying the economy stopped. The price for enslaved workers almost tripled.

Trade and Government Before the War

Merchants and Trade

Before the Civil War, trade in South Carolina was seen as less important than farming. Towns relied on nearby farms for business. Farmers could often grow their own food and make their own clothes. But in many areas, merchants were still needed to give farmers credit. This was important in a region where cash was scarce.

Inland merchants were rare compared to farmers until the mid-1800s. They gave credit to farmers to buy goods like coffee, sugar, and salt. The most common item sold was alcohol, and sales were usually small. Later in this period, merchants in the southwestern part of the state pushed for and received help from the government. This included allowing towns to form, tax breaks, and new roads to connect markets. These benefits often caused disagreements between town merchants and rural farmers. By the 1850s, trade was no longer just centered in Charleston. It began to grow in the upcountry too.

Before the economic downturn of 1819, Charleston was second only to New York in the value of its imports. Charleston's plantation owners relied on imports for building materials and food. The steamboat revolution of the 1820s weakened South Carolina's wagon trade. It allowed merchants in East Bay to control trade. Charleston's (and thus the state's) trading power began to decline in the 1820s. This was compared to ports in New York, New Orleans, and Mobile. But by the late 1830s, people who lived permanently in the state managed Charleston's trade for the first time.

Building Roads and Canals

Soon after the American Revolution, South Carolina was one of the first states to try big building projects. However, these plans mostly failed due to geography. First, the state's fast-flowing rivers made water transport difficult. Second, the mountains in the northwest stopped trade with Georgia. Also, the state's merchants already traded easily with Europe. So there was little demand for connecting the two states.

In 1818, the state created the Board of Internal Improvements. It set aside $1 million to build roads and canals. These would connect upcountry towns to Charleston. The board was closed in 1822. This was because the projects were behind schedule and over budget. Under a new leader, the projects still got money from the state for six more years. But the fast waters of the upcountry rivers were too strong for the canals. By 1840, most of the canals were ruined.

Charleston businessmen were sad to see cotton bales go to markets in Augusta and Savannah. So, they got permission to create the South Carolina Canal & Railroad Company (SCC&RR) in 1827. The company grew slowly. It also faced problems with getting land from citizens. The state allowed the company to force citizens to sell their land if they couldn't agree on a price. The price would be set by a group. This was a new idea in South Carolina law. Before, citizens were not paid for land needed for public use.

By the 1840s, the railroad connected the inland port of Hamburg and Charleston to the upcountry. At that time, it was the longest railroad line in the world under one management. It was the first successful big building project in the state, besides the Santee Canal. But success was limited, and money problems led the SCC&RR to merge. It joined with another company to form the South Carolina Railroad Company in 1843. The new company extended into the upcountry. This area had relied on river boats and wagons to move its cotton.

In the early 1850s, the state started giving money to railroad projects. By 1848, the South Carolina Railroad Company owned the only railroad line in the state, with 248 miles. But by 1860, South Carolina had eleven railroads with a total of 1000 miles of track.

One big failure during this time was the Blue Ridge Railroad. South Carolinians had long dreamed of connecting the port of Charleston to the northwest by train. In 1852, the Blue Ridge Railroad was created to make this dream real. Over six years, the state bought $2.5 million in company stock. But the Blue Ridge Railroad never got much private investment. The company failed to raise money without state help. Also, digging a one-mile-long tunnel through Stump House Mountain was very expensive. The company was closed in 1859.

Banking in Early SC

The first bank in South Carolina opened in Charleston in 1712. It operated until the Revolutionary War. Almost 20 years later, the new state government opened the Bank of South Carolina in 1792. Then in 1812, another bank was created, called the Bank of the State of South Carolina (BSSC). This was the state's own financial bank. The BSSC collected all taxes, arranged state loans, and paid state expenses. Any profits were used to pay off public debt. By 1820, there were five banks in Charleston, each with about $1 million in funds.

For most of the time before the Civil War, all private banks were in Charleston. This meant there was little money for trade outside Charleston. These areas used money from Georgia or North Carolina if it was available. Even though there was a growing need for banking in South Carolina's interior in the 1820s, the state government rarely allowed new banks to open. It also did not expand the BSSC, which only had branches in Charleston, Georgetown, Camden, and Columbia.

The BSSC's president, Stephen Elliot, wanted new banking ideas, like using paper money without tying it to gold. But in reality, his bank was very careful. Historian William Freehling called the BSSC "a restricted agricultural loan office." This was because its money was mostly tied up in long-term farm loans. In the end, the lack of short-term loans in the state's interior slowed down growth.

During the upcountry cotton boom of the 1830s, the area relied on money from the Bank of the United States and the Bank of England. This made it very sensitive to the economic crash of 1837. The area did not have its own bank until 1852. The BSSC also opened five offices in the region in the 1850s. Unlike the BSSC in the 1820s, these new banks and offices in the upcountry focused more on supporting trade than on farm loans.

Start of Factories

Early Manufacturing

Interest in factories in South Carolina depended on how well the cotton industry was doing. In decades with low cotton prices, like the 1840s, there was a lot of factory activity. But in good times, like the 1850s, manufacturing was not a main focus. While the state mainly produced rice and cotton before the Civil War, Charleston was still a manufacturing hub in the South.

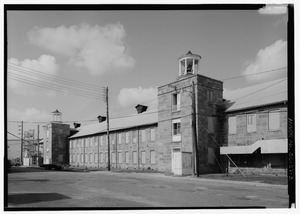

In Charleston, there were lumber and rice mills, railway car factories, and iron foundries. Manufacturing in Charleston was at its best in 1858, possibly worth $3 million. The city's foundries were very successful, selling products to almost every southern state. Also, no other state milled as much rice as South Carolina. By the 1860s, some industries in the city, like lumber mills and shipyards, were declining. Attempts at making textiles in the city had mostly failed.

The state's focus on farm crops meant it fell behind northern states in manufacturing. In 1860, Pennsylvania, a leading manufacturing state in the North, had $190 million in factory value. South Carolina had only $10.5 million. For most of the time before the Civil War, a lack of money stopped factories from being built. Also, these businesses rarely succeeded. The state simply could not build the skilled workforce needed to compete with the North.

Textile Industry

Because South Carolina had many cotton fields, textile mills appeared throughout the state. Most of these mills made low-quality cotton cloth. This was bought locally to clothe enslaved workers. Few of these mills lasted long until the Vaucluse Mill opened in 1833. At the start of the 1800s, state leaders believed that enslaved labor was more profitable for growing cotton than for weaving it.

William Gregg, a top manufacturer at the time, changed the industry. He opened the Graniteville Mill in 1847. By 1880, the mill had many machines and was selling good cotton products to the North. The company owned the houses where workers lived. This became common across the state. Gregg expected workers to live by his strict rules.

Until the 1840s, most mills used enslaved labor. From the 1850s to the early 1900s, the textile industry mostly hired white women and children. Between 1880 and 1920, textile makers from the Northeast moved to the Piedmont region. They were attracted by the state's anti-union views. The number of machines in the state grew 36 times, and the number of mills jumped from twelve to 184.

War and Recovery

South Carolina's economy was destroyed after the Civil War. Like other states in the Confederacy, South Carolina faced money problems. It could not sell cotton to Britain, its money lost value, and there were food shortages. Sherman's army burned Columbia, and Charleston was bombed for 587 days. Most importantly, the enslaved workers, in whom plantation owners had invested heavily, were freed.

In 1865, after the war, John Richard Dennett traveled through South Carolina. He wrote articles describing the state's condition. He found Columbia to be "ruins and silent desolation." In Beaufort County, large plantations were sold. Some went to Northerners, others were split into smaller plots and sold to freed people. This significant land ownership by freed people was unique but temporary.

Farming and Industry After the War

In the lowcountry, the first new industry after the Civil War was phosphate mining. Starting in the late 1860s, people mined phosphate to make fertilizer. They used labor from a program that leased inmates from the South Carolina Penitentiary, as well as freed people. As phosphate mining grew, the state's rice industry struggled. By 1868, fewer than 43 of the 52 rice plantations along the Cooper River were still working. In 1885, South Carolina supplied half of the world's phosphate. However, the 1886 Charleston earthquake and more phosphate from other Southern states ended this new industry. From 1893 to 1911, a series of hurricanes destroyed the rice industry. During this time, Charleston was one of the poorest towns in the region.

Soon after, the arrival of the boll weevil in 1917 ruined the state's cotton farms. By 1921, the sea cotton trade was almost gone. Charleston city officials tried to revive the city's economy. They tried to call the city the "Ellis Island of the South." They also opened the South Carolina Inter-State and West Indian Exposition. This event was meant to be like the World's Columbian Exposition. But it failed financially. The city's new Immigration Station received only one ship of immigrants.

Farming outside the lowcountry did better. World War I doubled the price and production of tobacco in South Carolina. This increased demand helped the Pee Dee region during the war. But the good times ended with the war. The state's tobacco industry struggled until new government policies in the 1930s made tobacco farming profitable again.

The New Deal

The Great Depression of the 1930s was terrible for South Carolina's already struggling economy. In 1933, the Federal Emergency Relief Administration helped a quarter of the state's citizens. That year, Charleston's unemployment reached 20 percent. The area lacked more than just jobs. A 1934 federal survey found "Charleston's housing facilities to be the worst in the nation." More than 100 buildings were constructed in the state from New Deal policies. These included Hunting Island State Park, the McKissick Museum, and a large part of the Citadel's campus.

The biggest project in the state was the Santee Cooper hydroelectric and flood-control project. It created both Lake Moultrie and Lake Marion. In 1930, only 3% of rural farms and homes in South Carolina had electricity. Santee Cooper provided many rural areas with electricity. It also helped the economy grow in South Carolina.

World War II and Defense

South Carolina received a contract for a naval yard in 1890. In 1901, construction began on the first dry dock north of Charleston. At first, the naval yard fixed and supplied ships. But in 1910, workers started building several cutters, gunboats, and submarine chasers. In 1917, before the country entered World War I, about 1,700 people worked at the naval yard. This number almost tripled to 5,600 during WWI.

Jobs at the yard dropped a lot after WWI. Throughout the 1920s and early 1930s, the Navy sometimes thought about closing the naval yard. But the naval yard was made a construction yard in 1933, which increased the workforce to 2,400. WWII had an even bigger effect. At its peak in 1944, the shipyard employed 26,000 people. This effectively created the city of North Charleston around it. The U.S. Army's training facility, Camp Croft, had a similar economic effect in Spartanburg.

Cold War Growth and Military Bases

After World War II, South Carolina's society was changing. The mill villages that had defined life for many were disappearing. Textile companies were combining. The civil rights movement challenged the state's culture of white supremacy. Also, the state saw a political shift led by Strom Thurmond and Olin D. Johnston. The long-standing conflict between urban and rural areas ended as factories became more important than farms.

The years after the war were good for the nation, especially for South Carolina. From 1945 to 1954, South Carolina's economy grew faster than the national average. The state's factories and people's incomes grew a lot in the 1950s. Money and skilled managers moved to the state, especially to the Piedmont region. From 1950 to 1955, the average income per person in the state increased by thirty percent. Even though the textile industry started to slow down in 1955, South Carolina's economy remained one of the fastest growing through the 1950s and early 1960s.

Thanks to U.S. Representative Mendal Rivers, military cuts after the war were smaller in South Carolina than in most other states. He helped get a new coast guard district in Charleston and a twelve-billion-dollar navy hospital in Beaufort. In 1945, the navy reorganized its activities in Charleston. It created the Charleston Naval Base. When it closed in 1996, the base was the largest employer of civilians in the state. It was responsible for a third of Charleston's economy. The base is now closed, but there are plans to make it a Coast Guard superbase.

In the early 1950s, the federal government built the Savannah River Plant (SRP). This plant made materials for hydrogen bombs. The plant, on 306 miles of land, was the largest building project in the country at the time. During construction, up to 40,000 workers were employed. This led to higher wages across the region. Civil rights groups fought for equal job opportunities at the plant. In the 1950s, most African Americans in the state worked in farming. This was because the textile industry was mostly white. The jobs created by the SRP in western South Carolina helped many white citizens there join the middle class. But African Americans, who made up 20% of the plant's workers, almost all worked as common laborers. In the 1990s, the plant was renamed the Savannah River Site (SRS). Today, the SRS manages nuclear materials, waste, and environmental cleanup. It has an annual budget of $2 billion and almost 11,000 workers.

South Carolina has eight military bases, including Joint Base Charleston and Fort Jackson. In 2017, the University of South Carolina estimated that these eight military bases had a total economic impact of $24.1 billion.

Modern Economy

As manufacturing, travel, and real estate grew, new people moved to South Carolina. This reversed a 150-year trend of people leaving the state. The manufacturing industry is growing especially fast. Between 2010 and 2018, jobs in advanced manufacturing doubled. This was largely thanks to many foreign car manufacturing companies in the upstate. Tourism, the state's largest industry, greatly affects real estate and finance. It is found almost entirely along South Carolina's coast. The poorest counties in the state are in the upper Pee Dee region and along the Savannah River near the Savannah River Site.

South Carolina State Ports

The South Carolina Port Authority (SCPA) was created in 1942. It owns and runs the state's public seaports. It also runs inland ports in Greer and Dillon. The ports in Charleston and Georgetown were open before the American Revolution. From the 1970s to the early 2000s, the port was one of the busiest on the East Coast. However, a failed expansion on Daniel Island slowed its growth. Still, between 2010 and 2020, the ports' cargo grew by 5.4 percent each year.

To better serve the state, SCPA opened two inland ports. Inland Port Greer opened in 2013. It supports the upstate's car industry. Inland Port Dillon opened in 2018. It connects the Pee Dee region to Charleston and the Southeast. The Port of Charleston is one of the busiest ports in North America. But the Port of Georgetown has been mostly closed. This is because it costs too much to keep its waters deep enough for ships.

The Port of Charleston was called a "small but busy regional operation" in the 1980s. It has grown with the booming population in the Southeast. Between 1976 and 1986, the ports in Charleston and Savannah grew 20%. Every other American port along the Atlantic Ocean declined. Because of Charleston's fast growth and the arrival of Panamax ships, the port started projects to increase its size. This included building a new terminal named after Hugh Leatherman. It cost $1 billion. There is also a new facility on the old navy yard. When fully built, the terminal is expected to double the port's capacity. The University of South Carolina Darla Moore School of Business estimated that the SCPA's yearly economic impact in the state was close to $63.4 billion in 2018.

In the next ten years, the SCPA plans to replace the Don Holt Bridge in North Charleston. This will allow large ships to dock at a renovated North Charleston Terminal. This terminal once handled a third of the port's containers. Now it handles about 200,000 containers a year, about 15 percent of the total. After being updated in the 2030s, the terminal is expected to handle up to 2 million containers a year. The Leatherman terminal is expected to reach its full capacity by 2040.

Upstate Car Manufacturing

The Upstate region is known as an industrial powerhouse. This is because many global companies are located there. At one point, the region had the "highest foreign investment per person in the United States." It also had one of the highest numbers of engineers in the country. The car manufacturing industry in the region has made South Carolina the top exporter of cars in the United States. In 1965, Hoechst was the first foreign company to move to South Carolina. It opened a plant in Spartanburg. At first, foreign investments were small. But that changed in 1970 when Michelin opened its first tire plant in the upstate.

Foreign investment grew across the country in the 1960s. This was due to President Nixon's new economic policies. But South Carolina had some special advantages that made it attractive to businesses. The state's well-known technical schools program, started by Governor Fritz Hollings in the 1960s, provided skilled workers. Also, transportation was good because of the Port of Charleston. South Carolina was also one of the first states to actively invite European business people. This made the state more known. From 1977 to 1987, the number of jobs provided by foreign companies in South Carolina rose from 35,000 to 75,700. These jobs replaced those lost from the textile industry, which began to decline in 1975.

The area along Interstate 85 in the upstate is known as "the Autobahn." This is because of the many German companies located there. In the early 1990s, BMW announced it would open its first manufacturing plant outside of Germany. It chose an area between Greenville and Spartanburg. This was because of the Upstate's access to Charlotte and Atlanta via the interstate. Also, the state had a nationally recognized technical school program. South Carolina beat out 250 other locations in ten countries to get BMW. To do this, the state offered a package of benefits. This included needed infrastructure and a $1-a-year lease for 1000 acres of land. The state bought this land from private owners. The plant was finished in 1995. It brought 2000 jobs to the area and many more from BMW suppliers. Historians say that the opening of this plant was the most important event for modern economic development. By 2006, the plant produced its millionth car. The next year, the plant had over 5,400 employees. BMW has invested almost $11 billion into the plant, making it the largest BMW plant in the world. A 2014 study estimated the plant's yearly economic impact in the state to be $16.6 billion. In 2018, South Carolina exported $3.7 billion worth of products to Germany. German companies made up one-third of all foreign investments in the state.

Aerospace Manufacturing

In October 2009, Boeing announced it would open a large assembly plant in North Charleston. It cost $2 billion to build. Earlier that year, Boeing had bought a Vought Aircraft facility in North Charleston. This was because Vought could not supply Boeing with parts on time. Boeing decided to expand in South Carolina instead of opening a second assembly line for the 787 Dreamliner in Washington state. A 2014 study found that since Boeing arrived, the aerospace manufacturing industry in the state has created almost as many jobs per year as the BMW plant did from 1990 to 2007. The study also estimated that the aerospace industry's economic impact was $8 billion a year from private businesses. It was $17 billion a year when including the state's military aviation facilities.

Lowcountry Car Manufacturing

2015 was a big year for the Lowcountry's economy. In March, Daimler announced plans to build a $500 million Mercedes Sprinter plant in North Charleston. Seven months later, Volvo Cars of North America also announced a $500 million car plant in Berkeley County. For Daimler, the plant was an expansion of an older facility. An expert from the College of Charleston estimated that the Volvo plant would have a yearly economic impact of $4.8 billion. In 2018, the Volvo plant invested another $600 million to expand production. In early 2023, the plant will start making a new all-electric version of the XC90. To do this, Volvo announced a battery plant in Fall 2020 on its North Charleston campus. The company expects the new XC90 production to quadruple the plant's workforce.

Lowcountry Tourism

South Carolina is a popular travel spot because of its beaches and historic cities. In 2018, travelers spent $14.4 billion on trips in South Carolina. Horry County (Myrtle Beach) accounted for $4.5 billion. Charleston County accounted for $2.6 billion. Beaufort County (Hilton Head) accounted for $1.4 billion.

Between 1924 and 1930, road mileage grew six times. This led to more car traffic and easier access. Better roads led to more development along the northern coast. Travel magazines also made the South seem more appealing. After World War II, tourism grew very fast in the United States. South Carolina started investing small amounts in advertising in the late 1940s. However, the state's tourism industry remained undeveloped for almost two decades. Only North Dakota and Rhode Island made less money from tourism than South Carolina in the 1950s. It was not until the South Carolina Department of Parks, Recreation, and Tourism was formed in 1967 that the state truly invested in tourism.

By 1977, the state's role in promoting tourism was seen as a national example. The next year, tourists spent $1.7 billion in South Carolina. The state ranked twentieth in the U.S. for number of tourists. In the 1980s, South Carolina competed with Florida for tourists. It started advertising itself as an international destination. Hurricane Hugo hit the state in 1989 and badly damaged the coast. But, strangely, the damage led to growth. This was because small beach buildings were destroyed, making space for larger condominiums. The Gullah/Geechee Heritage Corridor was created in 2006. It helps preserve the unique cultures of the lowcountry in South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida.

Tourism in Charleston

Charleston became a global tourist spot. This was largely due to its historic downtown, food scene, and the leadership of Joe Riley. He was the city's mayor for almost 40 years. First elected in 1975, Riley revitalized the city's downtown. He also made sure Charleston became the home for Spoleto Festival USA, a big arts festival. In the last three decades, the number of tourists and residents in Charleston grew a lot. From 1985 to 2018, the number of tourists almost quadrupled from 2 million to 7.3 million. Tourism brought in $8 billion in 2018. The population of the Charleston, Berkeley, and Dorchester counties grew from almost 507,000 residents in 1990 to 787,643 residents in 2018.

Growth in Charleston has had its problems. More people mean more traffic. The Lowcountry Corridor Plan is a $2 billion project to expand highways and fix traffic. The city also deals with gentrification. As the city developed, African American families moved out of downtown. For example, from 1950 to 2010, the number of Black residents in Charleston's East Side neighborhood dropped by 74%. At the same time, the number of white residents moving there rose by 83%.

Charleston's tourism industry took a while to fully develop. After a tourism boom in the 1880s, visitors often passed by Charleston on their way to Florida. Those who did visit Charleston were drawn to the city's old ruins and overgrown gardens, like Magnolia Plantation and Gardens. Between the World Wars, Charleston's many old homes began to be seen as something to protect. The best-selling novel Porgy (1925) helped make Charleston a tourist attraction. White visitors, about 47,000 from 1929 to 1930, saw the city's African American population as a sight to see. For most of the 1900s, Charleston tourism promoters offered a false and gentle idea of what Charleston was like before the Civil War.

Statistics and Inequality

In 2019, South Carolina's GDP (total value of goods and services) grew by 3.0%. However, 15.4% of the state's citizens lived below the poverty line. This was one of the highest rates in the nation. That year, South Carolina's GDP was $249.9 billion. This made it the 26th largest state economy. It was half the size of neighboring Georgia and North Carolina. Also, while South Carolina's unemployment rate was 2.4%, its GDP per person was $41,457. This was among the lowest in the country.

The 2020 Census showed that South Carolina's population grew by almost 500,000 people since 2010. The counties with the highest growth rates were Horry County (30.4% increase), Berkeley County (29.2% increase), York County, and Lancaster County. In contrast, the rural counties of Allendale, Bamberg, and Lee each lost over 14% of their population.

The Great Recession in 2008 caused home values to drop nationwide. But houses in mostly African American neighborhoods were the least likely to recover. Land ownership by African Americans in the state declined throughout the 1900s. For the Gullah/Geechee community, this loss was often due to forced sales of shared land. Across the nation, the income gap between African Americans and Caucasians has not changed in 70 years. In Charleston, Black citizens earn 60% of what white citizens make. Also, in Charleston, Black applicants with high incomes were rejected for home loans 31% of the time between 2005 and 2014. White applicants with high incomes were rejected 10% of the time.

South Carolina has very few affordable homes. In 2016, it had the worst eviction rate in the country. It was almost twice as high as the next state.

Recent Economic Developments (2019–2023)

South Carolina did better economically than many states during the COVID-19 pandemic, especially in the upstate. By the end of 2020, the state's unemployment rate was 4.2%. However, experts expected South Carolina to return to its pre-pandemic job levels by February 2022. South Carolina's real GDP (total value of goods and services, adjusted for inflation) fell 4.1% from 2019 to 2020.

Still, investments were made in the state. Mark Anthony Brewing announced a $400 million facility in Richland County. It will make White Claw Hard Seltzer. This facility is expected to create 300 jobs. Also, E & J Gallo Winery announced plans to build a $400 million bottling facility in Fort Lawn. This is expected to create 500 jobs. The federal government also gave $25 million to help build a new rail line. This line will transport vehicles from Volvo's plant to distribution centers inland. The line will run near the new state-owned Camp Hall Commerce Park, a nearly 4,000-acre business park.

In 2021, the PGA Tour had what one person called "the South Carolina swing." The state hosted the RBC Heritage on Hilton Head Island in April. It hosted a PGA Championship at Kiawah Island in May. After the Canadian Open was canceled, the PGA announced South Carolina would host another tournament. This was the Palmetto Championship at Congaree in June. This last tournament was expected to bring in about $50 million in tourism money.

In 2022 and 2023, many large economic projects were announced. In 2022, over ten billion dollars in new investments were announced for South Carolina. This included a $3.5 billion car battery recycling and production facility in Berkeley County. There was also a new $1.7 billion BMW facility in the upstate. And a large car battery facility in Florence County costing almost $1 billion. In March 2023, Scout Motors announced it was opening a $2 billion electric vehicle manufacturing facility near Columbia. This is the first large car factory in South Carolina's midlands region. Governor Henry McMaster announced he would ask for $1.3 billion in state help, including money for roads, to secure Scout Motors' investment.

Images for kids