Edward S. Curtis facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

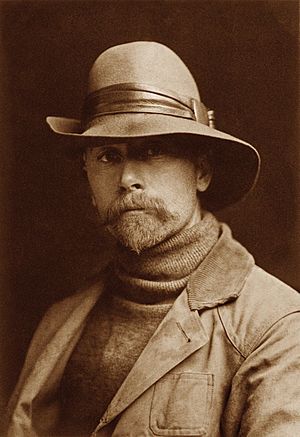

Edward S. Curtis

|

|

|---|---|

Self-portrait circa 1889

|

|

| Born |

Edward Sheriff Curtis

February 19, 1868 Whitewater, Wisconsin, United States

|

| Died | October 19, 1952 (aged 84) Los Angeles, California, United States

|

| Occupation | Photographer, ethnologist |

| Spouse(s) | Clara J. Phillips (1874–1932) |

| Children | Harold Curtis (1893–1988) Elizabeth M. Curtis (1896–1973) Florence Curtis Graybill (1899–1987) Katherine Curtis (1909–unknown) |

| Parent(s) | Ellen Sheriff (1844–1912) Johnson Asahel Curtis (1840–87) |

Edward Sheriff Curtis (born February 19, 1868 – died October 19, 1952) was a famous American photographer. He was also an ethnologist, which means he studied different cultures and peoples. Curtis is best known for his amazing photos of the American West and the many different Native American tribes. He spent a big part of his life documenting their traditions and ways of life.

Contents

Edward Curtis's Early Life and Photography Journey

Edward Curtis was born on February 19, 1868, on a farm in Whitewater, Wisconsin. His father, Johnson Asahel Curtis, was a minister and farmer who had been in the American Civil War. His mother was Ellen Sheriff. Edward had several brothers and sisters.

His family faced tough times and poverty. Around 1874, they moved to Minnesota. Edward left school after the sixth grade. Even at a young age, he was interested in photography and built his own camera.

Starting His Photography Career

In 1885, when he was 17, Curtis began working as a photographer's helper in Saint Paul, Minnesota. Two years later, his family moved to Seattle, Washington. There, he bought a new camera and became a partner in a photography studio.

He later started his own studio called Curtis and Guptill. This was the beginning of his long and important career.

First Photos of Native Americans

In 1895, Curtis met and photographed Princess Angeline (around 1820–1896). She was the daughter of Chief Seattle from the Duwamish tribe. This was the first time he took a portrait of a Native American person.

His work quickly gained attention. In 1898, three of his photos were shown in a big exhibition. Two of them were of Princess Angeline. One of his photos, "Homeward," won a grand prize and a gold medal.

That same year, while photographing Mount Rainier, Curtis met a group of scientists who were lost. One of them was George Bird Grinnell, an expert on Native Americans. This meeting changed Curtis's life.

Grinnell invited Curtis to join a trip to photograph the Blackfoot Confederacy in Montana in 1900. Curtis also became the official photographer for the Harriman Alaska Expedition in 1899. These experiences helped him learn a lot and deepened his interest in Native American cultures.

The North American Indian Project

In 1906, a wealthy man named J. P. Morgan gave Edward Curtis $75,000. This money was to help Curtis create a huge series of books about Native Americans. The plan was to make 20 books with 1,500 photographs.

Curtis worked on this project for more than 20 years. He didn't get a salary for himself. The money was only for his travels and research.

Working on the Project

With the funding, Curtis hired a team to help him. William E. Myers helped with writing and recording Native American languages. Bill Phillips helped with planning and fieldwork.

One of the most important people he hired was Frederick Webb Hodge. Hodge was an anthropologist from the Smithsonian Institution. He helped edit the entire series of books.

Curtis's main goal was not just to take pictures. He wanted to record as much as possible about Native American traditional life. He believed this way of life was disappearing quickly. He wrote in his first book in 1907 that this information "must be collected at once or the opportunity will be lost."

What Curtis Documented

Curtis made over 10,000 recordings of Native American languages and music. He took more than 40,000 photos of people from over 80 different tribes. He wrote down tribal stories and history.

He also described their traditional foods, homes, clothes, games, ceremonies, and funeral customs. For many tribes, his work is the only written record of their history and traditions.

In the Land of the Head Hunters Film

Since 1906, Curtis had been using motion picture cameras in his fieldwork. In 1912, he decided to make a full-length movie about Native American life. He wanted to show their culture and also improve his financial situation.

Curtis chose the Kwakiutl tribe from British Columbia, Canada, for his film. His movie, In the Land of the Head Hunters, was special. It was the first feature film where all the actors were Native North Americans.

The film first showed in New York and Seattle on December 7, 1914. It was a silent film with music. Critics liked it, but it didn't make much money. Some experts later said the film wasn't fully accurate because Curtis had some actors dress up in ways that weren't always traditional.

Later Years and Legacy

Around 1922, Curtis moved to Los Angeles. He opened a new photo studio there. He also worked as an assistant cameraman for famous director Cecil B. DeMille. He even helped film The Ten Commandments in 1923.

In 1924, Curtis sold the rights to his film In the Land of the Head-Hunters to the American Museum of Natural History. He sold it for $1,500, even though it cost him over $20,000 to make.

In 1928, Curtis sold the rights to his big The North American Indian project to J. P. Morgan Jr. The last book in the series was published in 1930. About 280 complete sets of his amazing work were sold.

Loss of His Work's Rights

In 1935, the rights to The North American Indian were sold again. This time, they went to a company in Boston for only $1,000. This sale included the remaining books, thousands of prints, the copper printing plates, and the original glass negatives.

Many of these materials were stored in a basement and forgotten until 1972. Sadly, some of his original glass negatives were destroyed or sold as junk during World War II.

Family Life

In 1892, Edward Curtis married Clara J. Phillips. They had four children: Harold, Elizabeth (Beth), Florence, and Katherine.

Curtis was often away from home for long periods while working on The North American Indian. This left Clara to take care of their children and the photo studio. They eventually divorced in 1919. As part of the divorce, Clara received his photo studio and all his original camera negatives.

To prevent his ex-wife from owning them, Curtis and his daughter Beth destroyed many of his original glass negatives.

Death and Rediscovery

Edward Curtis passed away on October 19, 1952, at the age of 84. He died from a heart attack at his daughter Beth's home in Los Angeles.

For a long time after his death, Curtis's work was largely forgotten. However, in the 1960s and 1970s, people became interested in his photographs again. His work was shown in major art exhibitions. Original sets of The North American Indian started selling for very high prices. This renewed interest was part of a larger focus on Native American issues during that time.

Collections of Edward Curtis's Work

Many places today keep and share Edward Curtis's important work.

Northwestern University

You can find all 20 volumes of The North American Indian online through Northwestern University. This includes all the text and photos.

Library of Congress

The Library of Congress has over 2,400 of Curtis's original photographic prints. These were made from his glass negatives. About two-thirds of these images were never published in The North American Indian. They offer a unique look at his work.

Peabody Essex Museum

The Peabody Essex Museum has 110 special prints that Curtis made for an exhibit in 1905–06. These prints are very rare and in perfect condition.

Indiana University

Indiana University has 276 of the wax cylinder recordings Curtis made between 1907 and 1913. These recordings capture the music and languages of many different Native American groups.

University of Wyoming

The Toppan Rare Books Library at the University of Wyoming has a complete set of all 20 volumes of The North American Indian.

Books by Edward Curtis

- The North American Indian. 20 volumes (1907–1930)

- Volume 1 (1907): The Apache. The Jicarillas. The Navaho.

- Volume 2 (1908): The Pima. The Papago. The Qahatika. The Mohave. The Yuma. The Maricopa. The Walapai. The Havasupai. The Apache-Mohave, or Yavapai.

- Volume 3 (1908): The Teton Sioux. The Yanktonai. The Assiniboin.

- Volume 4 (1909): The Apsaroke, or Crows. The Hidatsa.

- Volume 5 (1909): The Mandan. The Arikara. The Atsina.

- Volume 6 (1911): The Piegan. The Cheyenne. The Arapaho.

- Volume 7 (1911): The Yakima. The Klickitat. Salishan tribes of the interior. The Kutenai.

- Volume 8 (1911): The Nez Perces. Wallawalla. Umatilla. Cayuse. The Chinookan tribes.

- Volume 9 (1913): The Salishan tribes of the coast. The Chimakum and the Quilliute. The Willapa.

- Volume 10 (1915): The Kwakiutl.

- Volume 11 (1916): The Nootka. The Haida.

- Volume 12 (1922): The Hopi.

- Volume 13 (1924): The Hupa. The Yurok. The Karok. The Wiyot. Tolowa and Tututni. The Shasta. The Achomawi. The Klamath.

- Volume 14 (1924): The Kato. The Wailaki. The Yuki. The Pomo. The Wintun. The Maidu. The Miwok. The Yokuts.

- Volume 15 (1926): Southern California Shoshoneans. The Diegueños. Plateau Shoshoneans. The Washo.

- Volume 16 (1926): The Tiwa. The Keres.

- Volume 17 (1926): The Tewa. The Zuñi.

- Volume 18 (1928): The Chipewyan. The Western Woods Cree. The Sarsi.

- Volume 19 (1930): The Indians of Oklahoma. The Wichita. The Southern Cheyenne. The Oto. The Comanche. The Peyote Cult.

- Volume 20 (1930): The Alaskan Eskimo. The Nunivak. The Eskimo of Hooper Bay. The Eskimo of King Island. The Eskimo of Little Diomede Island. The Eskimo of Cape Prince of Wales. The Kotzebue Eskimo. The Noatak. The Kobuk. The Selawik.

Articles by Edward Curtis

- "The Rush to the Klondike Over the Mountain Pass". The Century Magazine, March 1898, pp. 692–697.

- "Vanishing Indian Types: The Tribes of the Southwest". Scribner's Magazine 39:5 (May 1906): 513–529.

- "Vanishing Indian Types: The Tribes of the Northwest Plains". Scribner's Magazine 39:6 (June 1906): 657–71.

- "Indians of the Stone Houses". Scribner's Magazine 45:2 (1909): 161–75.

- "Village Tribes of the Desert Land. Scribner's Magazine 45:3 (1909): 274–87.

Images for kids

-

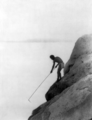

A smoky day at the Sugar Bowl—Hupa, c. 1923. Hupa man with spear, standing on rock midstream, in background, fog partially obscures trees on mountainsides.

-

Navajo medicine man – Nesjaja Hatali, c. 1907

-

White Man Runs Him, c. 1908. Crow scout serving with George Armstrong Custer's 1876 expeditions against the Sioux and Northern Cheyenne that culminated in the Battle of the Little Bighorn.

-

The old-time warrior: Nez Percé, c. 1910. Nez Percé man, wearing loin cloth and moccasins, on horseback.

-

Crow's Heart, Mandan, c. 1908

-

Mandan man overlooking the Missouri River, c. 1908

-

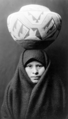

Zuni Girl with Jar, c. 1903. Head-and-shoulders portrait of a Zuni girl with a pottery jar on her head.

-

Cheyenne maiden, 1930

-

Hopi mother, 1922

-

Hopi girl, 1922

-

Canyon de Chelly – Navajo. Seven riders on horseback and dog trek against background of canyon cliffs, 1904

-

Mandan lodge, North Dakota, c. 1908

-

Food caches, Hooper Bay, Alaska, c. 1929

-

Boys in kayak, Nunivak, 1930

See also

In Spanish: Edward Sheriff Curtis para niños

In Spanish: Edward Sheriff Curtis para niños

| Leon Lynch |

| Milton P. Webster |

| Ferdinand Smith |