H. H. Asquith facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

The Earl of Oxford and Asquith

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Asquith c. 1910s

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister of the United Kingdom | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 5 April 1908 – 5 December 1916 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monarch | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Henry Campbell-Bannerman | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | David Lloyd George | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Leader of the Opposition | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 12 February 1920 – 21 November 1922 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monarch | George V | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Donald Maclean | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Ramsay MacDonald | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 6 December 1916 – 14 December 1918 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monarch | George V | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister | David Lloyd George | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Edward Carson | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Donald Maclean | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Leader of the Liberal Party | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 30 April 1908 – 14 October 1926 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Henry Campbell-Bannerman | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | David Lloyd George | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born |

Herbert Asquith

12 September 1852 Morley, West Riding of Yorkshire, England |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 15 February 1928 (aged 75) Sutton Courtenay, Berkshire, England |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Resting place | All Saints' Church, Sutton Courtenay | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Political party | Liberal | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spouses |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | 10, including Raymond, Herbert, Arthur, Violet, Cyril, Elizabeth and Anthony | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Education | City of London School | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alma mater |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Profession | Barrister | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Signature |  |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Herbert Henry Asquith, also known as H. H. Asquith, was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1908 to 1916. He was a member of the Liberal Party. Asquith was the last Liberal prime minister to lead a government with a clear majority in Parliament. He played a big part in creating new laws that helped people, like welfare reforms, and he reduced the power of the House of Lords. In August 1914, Asquith led Great Britain and the British Empire into World War I. His government faced challenges during the war, especially due to a shortage of supplies and the failure of the Gallipoli Campaign. He formed a government with other parties in 1915 but resigned in December 1916. He never became prime minister again.

After studying at Balliol College, Oxford, Asquith became a successful barrister (a type of lawyer). In 1886, he became a Member of Parliament (MP) for East Fife, a seat he held for over 30 years. He became Home Secretary in 1892 and Chancellor of the Exchequer in 1905. In 1908, he became Prime Minister. His government worked to pass many reforms. When the House of Lords rejected his budget in 1909, Asquith called an election. After another election in 1910, he passed the Parliament Act 1911, which limited the power of the House of Lords. He also faced big challenges with Irish Home Rule, which almost led to civil war.

When Britain declared war on Germany in 1914, conflicts over Ireland and women's voting rights were put on hold. Asquith focused on getting the country ready for war, sending troops to the Western Front, and making sure the country had enough supplies. However, as the war continued, people wanted stronger leadership. He formed a coalition government with other parties in 1915. But he was seen as slow to make decisions, especially about military strategy and how to pay for the war. David Lloyd George replaced him as prime minister in December 1916. Asquith's role in creating the modern British welfare state (1906–1911) is often praised. But historians have also pointed out his weaknesses as a war leader and as a party leader after 1914. He was the only Prime Minister between 1827 and 1979 to serve more than eight years in a row.

Contents

Early Life and Political Start: 1852–1908

Family Background and Childhood

Herbert Henry Asquith was born in Morley, England, on 12 September 1852. He was the younger son of Joseph Dixon Asquith and Emily Willans. The Asquith family had a long history in Yorkshire and were nonconformists (Protestants who were not part of the Church of England). Both of Asquith's parents came from families involved in the wool trade. His father's company was Gillroyd Mill, and his mother's father ran a successful wool-trading business. Both families were middle-class, Congregationalist, and politically radical.

Asquith's father died suddenly in 1860. His mother's brother, William Willans, took care of the family and arranged for the boys' schooling. After attending Huddersfield College, they went to Fulneck School, a boarding school near Leeds. In 1863, William Willans died, and the family was then looked after by another uncle, John Willans. The boys moved to London to live with him. When his uncle moved back to Yorkshire, Asquith stayed in London, living with different families. He later said he felt like an "orphan" during this time. He considered himself a "Londoner" after this, but his nonconformist background from the North still influenced him.

Education and University Life

Asquith and his brother attended the City of London School. The headmaster, E. A. Abbott, was a brilliant classical scholar. Asquith became an outstanding student, especially in classics and English. He loved reading and became very interested in public speaking. He often visited the House of Commons to watch debates and practiced his own speaking skills in the school's debating society. His teachers noticed how clear and logical his speeches were, a quality he was known for throughout his life.

In 1869, Asquith won a scholarship to Balliol College, Oxford. He started there in October 1870. The college was very respected, and Asquith did very well in his studies. He enjoyed debating and quickly became active in the Oxford Union, a famous debating society. He was elected Treasurer of the Union in 1872 and later became its President in 1874. He graduated with top honors in his studies.

Starting a Career in Law

After graduating in 1874, Asquith decided to become a barrister. He trained at Lincoln's Inn and was officially called to the bar in June 1876. The first few years were tough, and he didn't get many cases. He started a legal practice with two other young barristers. He was very honest and didn't like using tricky legal methods.

In 1877, he married Helen Kelsall Melland. They had five children: Raymond, Herbert, Arthur, Violet, and Cyril. Helen had some money of her own, so they lived comfortably in Hampstead.

To earn more money, Asquith wrote articles for The Spectator, a newspaper with Liberal views. He also wrote for The Economist and taught evening classes. His articles showed his strong radical political views. He supported the British Empire and, later, self-rule for Ireland. He was against women getting the right to vote for most of his career, believing it would mostly help the Conservative Party.

Asquith's legal career improved in 1883 when he joined the law firm of R. S. Wright. Wright was a government lawyer, and Asquith's work for him impressed important politicians like Prime Minister W. E. Gladstone. This helped raise Asquith's profile and brought him more legal work, especially from large businesses.

Becoming a Member of Parliament

In June 1886, a general election was called. Asquith became the Liberal candidate for East Fife in Scotland. He won the election and became a Member of Parliament. The Liberals lost the election overall, so Asquith started his parliamentary career as an opposition MP. His first speech in March 1887 was against a Conservative bill about Ireland. From the beginning, other MPs were impressed by his clear speaking style and authority.

His legal career continued to do well. He disliked arguing in front of juries but was excellent at arguing complex civil law cases before judges. In 1889, he gained a big boost when he was part of the legal team for the Parnell Commission of Enquiry. Within a year, he became a Queen's Counsel (QC), a senior rank for barristers.

Personal Changes and Cabinet Role

In September 1891, Asquith's first wife, Helen, died from typhoid fever. He bought a house in Surrey and hired staff to care for his children. He also kept a flat in London for work.

In July 1892, another general election brought Gladstone and the Liberals back to power. Asquith, at 39, was appointed Home Secretary, a very important position in the Cabinet. The government faced challenges because the Conservatives and their allies had more power in Parliament. Asquith tried to pass bills to separate the Church of Wales from the state and to protect workers, but they were defeated. Still, he gained a reputation as a fair and capable minister.

Gladstone retired in 1894, and Lord Rosebery became the new prime minister. Asquith stayed as Home Secretary until the government lost power in 1895.

On 10 May 1894, Asquith married Margot Tennant. Margot was very different from his first wife – outgoing and lively. Despite some worries from his friends, their marriage was successful. Margot got along with his children, and they had two children who survived infancy: Anthony and Elizabeth.

Out of Office and Return to Power

The general election of July 1895 was a big loss for the Liberals. Asquith was no longer in government, so he focused on his legal work. He earned a good income as a QC. The Liberal Party faced internal disagreements during this time. Asquith was pressured to become the party leader, but he couldn't afford to give up his legal income. So, Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman became the Liberal leader.

During the Boer War (1899–1902), Liberals were divided, but Asquith supported the British Empire. He strongly argued for traditional Liberal policies like free trade, which meant no taxes on imported goods. This became a major political issue, and Asquith's arguments helped unite the Liberals against the Conservatives' idea of tariffs (taxes on imports).

In December 1905, the Conservative Prime Minister, Arthur Balfour, resigned. King Edward VII asked Campbell-Bannerman to form a government. Asquith was appointed Chancellor of the Exchequer, responsible for the country's money.

A month later, in January 1906, Campbell-Bannerman called a general election, and the Liberals won by a huge margin. As Chancellor, Asquith laid the groundwork for new social welfare programs. He introduced a different income tax system, taxing higher incomes more and earned income less. He used this money to fund old-age pensions, which was the first time the British government provided such support.

Campbell-Bannerman's health declined, and he resigned on 3 April 1908. Asquith was the clear choice to succeed him. King Edward, who was in France, sent for Asquith. Asquith traveled to Biarritz, France, and officially became Prime Minister on 8 April.

Leading the Country: 1908–1914

New Government and Daily Life

When Asquith returned from France, his leadership of the Liberal Party was confirmed. He changed some of his Cabinet ministers. David Lloyd George became the new Chancellor, and Winston Churchill became President of the Board of Trade, joining the Cabinet at a young age. Asquith removed some ministers from the previous government, which caused some hard feelings. However, his new Cabinet was seen as a strong team, balancing different groups within the Liberal Party.

Asquith was known for working quickly, which gave him time for his hobbies. He loved reading classics, poetry, and English literature. He also enjoyed writing letters, as he disliked using the telephone. He often traveled to country houses and spent summers in Scotland, playing golf and attending events at Balmoral. In 1912, he and Margot bought a country house called The Wharf in Berkshire. He also enjoyed playing Contract bridge.

Asquith enjoyed company and conversation, especially with clever women. He had a group of close female friends. His love for comfort and luxury, even during times of crisis, sometimes made people feel he was out of touch.

Changing the House of Lords

Asquith wanted to guide his Cabinet as they passed new laws. But he soon faced a big challenge from the House of Lords. Even though the Liberals had a huge majority in the House of Commons, the Conservatives had strong control over the unelected House of Lords. The Lords had often blocked or changed bills passed by the Liberal government.

Asquith and Lloyd George believed that the Lords would not dare to block a finance bill (a bill about taxes and spending), as they hadn't done so since the 17th century. So, they decided to include their reform plans within the annual budget.

The People's Budget of 1909

In December 1908, Asquith announced that the upcoming budget would reflect the Liberals' goals. The People's Budget, presented by Lloyd George in 1909, greatly expanded social welfare programs. To pay for these, it increased taxes on land, high incomes, tobacco, beer, and spirits. It also introduced a tax on petrol. Some Liberals disagreed with the budget, calling it "Socialistic."

The budget caused a lot of debate throughout 1909. Newspapers like The Times urged the House of Lords to reject it. Many public meetings were held to protest the budget. Lloyd George famously criticized the wealthy, saying that "a fully-equipped duke costs as much to keep up as two Dreadnoughts." King Edward privately encouraged Conservative leaders to pass the Budget.

By July, it became clear that the Conservative-controlled House of Lords would reject the budget, hoping to force an election. The budget passed the Commons on 4 November 1909 but was rejected by the Lords on 30 November. Asquith then asked the King to dissolve Parliament for an election in January 1910.

Elections and Constitutional Crisis: 1910–1911

The January 1910 election was mainly about limiting the Lords' power. Asquith hinted that he might ask the King to create many new Liberal peers to force the bill through the Lords. However, the King had told Asquith he would only consider this after a second general election.

The election resulted in a "hung parliament," meaning no party had a clear majority. The Liberals lost many seats but still had more than the Conservatives. With support from Irish Nationalist and Labour MPs, Asquith's government had enough votes for most issues.

The Irish MPs wanted to remove the Lords' power to block Irish Home Rule. They threatened to vote against the budget unless their demands were met. Asquith had to find a way to limit the Lords' veto without upsetting the Irish and Labour parties.

The budget passed the Commons again and was approved by the Lords in April. The Cabinet decided on a plan: a bill passed by the Commons in three consecutive yearly sessions would become law even without the Lords' approval. They would resign if the King didn't promise to create enough Liberal peers to pass the bill. On 14 April 1910, the Commons passed resolutions that would become the basis of the Parliament Act 1911.

These plans were put on hold when King Edward VII died on 6 May 1910. Asquith and his ministers were hesitant to pressure the new king, George V. Asquith and Conservative leaders held talks throughout 1910, but they failed in November because the Conservatives insisted on the Lords keeping their veto over Irish Home Rule.

On 11 November, Asquith asked King George to dissolve Parliament for another general election in December. He also demanded that the King promise to create enough Liberal peers to pass the Parliament Bill. The King reluctantly agreed, writing in his diary that it was the only way to avoid the Cabinet resigning.

Asquith led the election campaign, focusing on the Lords' veto. The election results showed little change in party strengths. Asquith remained Prime Minister. The Parliament Bill passed the House of Commons again in April 1911. The Lords made many changes to it. Asquith told King George that new peers would be created, and the King agreed. After much debate, on 10 August 1911, the Lords narrowly voted not to insist on their changes, and the bill became law.

This period was a high point for Asquith's time as prime minister. He skillfully guided the country through a major constitutional crisis.

Social and Labor Reforms

Despite the focus on the House of Lords, Asquith's government passed many important reform laws. These included:

- Labor exchanges: Offices that helped people find jobs.

- Unemployment and health insurance: Early forms of social security to help people who lost their jobs or got sick.

- Old-age pensions: Providing money to elderly people, which started in 1908. This was a big step, though the amounts were small.

- Trade Union Act 1913: This law helped trade unions by reversing a previous court decision.

- Salaries for MPs: In 1911, MPs started receiving salaries, making it possible for working-class people to serve in Parliament.

Asquith was not a "New Liberal" himself, but he understood the need for the government to play a bigger role in helping people. He also wanted to keep the support of the Labour Party.

The government also faced a controversy in 1908 over a Catholic procession in London. An old law forbade such events. Asquith managed to get the organizers to change their plans, but it led to the resignation of his only Catholic minister.

The disestablishment of the Welsh Church (separating it from the state) was another Liberal goal. The bill was rejected twice by the Lords but finally passed in September 1914. Its provisions were put on hold until after the war.

Women's Voting Rights

Asquith had opposed votes for women since 1882 and remained against it as prime minister. He believed that voting rights should only be given if it improved government, not as a matter of rights. He didn't fully understand the strong feelings on both sides of the issue.

Militant suffragettes, who wanted women to vote, often targeted Asquith. They tried to meet him, confronted him at parties, and even ambushed him. These incidents did not change his mind, as he didn't believe they represented public opinion.

Many in his Cabinet, including Lloyd George and Churchill, supported women's suffrage. Asquith reluctantly agreed to allow a vote on an amendment to a reform bill that would give women the vote. However, the Speaker of the House ruled that the amendment changed the bill too much, so it was withdrawn. Asquith was privately relieved.

Asquith eventually supported women's suffrage in 1917, after he was no longer prime minister. Women over 30 were finally given the right to vote in 1918 by Lloyd George's government. Asquith's reforms to the House of Lords helped make this possible.

Irish Home Rule

After the 1910 elections, the Liberals needed the support of Irish MPs, led by John Redmond. To get their help with the budget and the Parliament Bill, Asquith promised that Irish Home Rule (self-government for Ireland) would be a top priority. This issue turned out to be very complicated.

The idea of self-government for Ireland had been a Liberal goal since 1886. However, Asquith had previously been cautious about relying on Irish Nationalist support. After 1910, their votes were essential for his government to stay in power. The goal was to keep Ireland part of the United Kingdom but give it more control over its own affairs. The Conservatives, especially those from Protestant Ulster, strongly opposed Home Rule.

The Third Home Rule Bill was introduced in April 1912. It did not include any special status for Protestant Ulster, which was mostly Catholic. Neither side was fully happy with the bill. Irish Nationalists supported it, expecting more self-government over time. Conservatives and Irish Unionists opposed it. Unionists in Ulster began preparing to resist Home Rule by force, even forming the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF).

Asquith remained calm despite the strong emotions. He believed that the issue of dividing County Tyrone, which had a mixed population, was "inconceivably small" to English eyes but "immeasurably big" to Irish eyes. He said in 1912 that "Ireland is a nation, not two nations but one nation."

In April 1914, the "Curragh incident" occurred. About 60 army officers, led by Brigadier-General Hubert Gough, said they would rather resign than force Home Rule on Ulster. Asquith acted to calm the situation, asking the Secretary of State for War, John Seely, and the head of the army, Sir John French, to resign. Asquith then took over the War Office himself until the war began.

Soon after, the UVF secretly landed a large shipment of guns and ammunition at Larne. Asquith decided not to arrest their leaders. He announced that the Home Rule bill would pass but would not take effect until after the war. A separate bill for Ulster's special status would be considered. This solution satisfied no one. The crisis was put on hold when World War I broke out.

Foreign Policy and Defence

Asquith led a Liberal Party that was divided on foreign policy and military spending. Britain and France had formed the Entente Cordiale, a friendly agreement. In 1906, there was a crisis between France and Germany over Morocco. The French asked for British help if there was a conflict. The Foreign Secretary, Sir Edward Grey, agreed to military talks with France, but the Cabinet was not fully aware of these until 1911. Asquith was concerned that France might assume Britain would help in a war, but Grey convinced him the talks were necessary.

Another major issue was the naval arms race with Germany. Britain and Germany were building more powerful battleships called "dreadnoughts." Asquith's First Lord of the Admiralty, Reginald McKenna, proposed building eight more British dreadnoughts. This caused arguments within the Cabinet between those who supported more spending and those who wanted to save money. Asquith found a compromise: four ships would be built immediately, and four more if needed.

The Agadir crisis in 1911, another dispute between France and Germany over Morocco, showed Britain's support for France. Lloyd George gave a speech that signaled Britain's friendly stance. The Cabinet agreed that no talks should commit Britain to war without their approval. However, by 1912, Britain and France had further naval agreements. Asquith assured MPs that Britain was not secretly committed to war.

July Crisis and World War I

The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria on 28 June 1914 led to a month of failed diplomatic efforts to prevent war. Britain's Foreign Secretary, Sir Edward Grey, proposed a conference, but Germany rejected it. Many in Asquith's Cabinet were against Britain getting involved in a war. Asquith himself was unsure if Britain needed to join. On 24 July, he wrote that Britain might just be "spectators."

However, as the situation worsened, Asquith realized war was unavoidable. He supported Grey's commitment to Anglo-French unity. On 2 August, he received confirmation of support from the Conservative leader, Bonar Law. Grey informed the Cabinet about the Anglo-French naval talks, and Asquith secured agreement to mobilize the British fleet.

On 3 August, Belgium rejected Germany's demand for free passage through its country. Grey spoke in the Commons, calling for British action against Germany's aggression. The next day, Asquith met the King, and Britain issued an ultimatum to Germany, demanding withdrawal from Belgium. When Germany did not respond by the deadline, Britain declared war on 4 August 1914.

First Year of World War I: 1914–1915

Asquith's Wartime Government

When war was declared, Asquith led an almost united Liberal Party. Only two ministers resigned from his Cabinet. With other parties promising to cooperate, Asquith's government led a united nation into war.

In the early months of the war, Asquith's popularity grew. People saw him as steady and reliable. However, his leadership style, which worked well in peacetime, was not suited for a total war. He would eventually lose his position, and his party would never again form a majority government.

Asquith made one important change to his Cabinet: he gave up the War Office and appointed Lord Kitchener, a well-known military figure, as Secretary of State for War. Kitchener's involvement strengthened the government's image. Lloyd George remained Chancellor, and Grey stayed as Foreign Secretary.

The German invasion of Belgium led to trench warfare on the Western Front. This stalemate caused growing frustration with the government and Asquith. People and the press blamed him for not being energetic enough in leading the war effort. This also created divisions within the Cabinet. Some, like Asquith, believed victory lay in sending more men and supplies to France and Belgium. Others, like Churchill and Lloyd George, thought the Western Front was stuck and wanted to focus on action in the East.

Dardanelles Campaign

The Dardanelles Campaign was an attempt by Churchill and others to break the stalemate on the Western Front. The plan was for British and French forces to land on Turkey's Gallipoli Peninsula and quickly advance to Constantinople, forcing Turkey out of the war. However, the plan was rejected by Admiral Fisher and Lord Kitchener. Asquith tried to mediate between them and Churchill, which led to delays.

The naval attack failed. Allied troops landed on Gallipoli but were delayed in getting reinforcements, allowing the Turks to regroup. This led to another stalemate. The Allies suffered from poor leadership, bad equipment, and a lack of planning. They faced strong Ottoman forces and suffered huge casualties. The campaign was a political disaster for Churchill and badly hurt Asquith's reputation.

Shell Crisis of May 1915

In early 1915, there were growing disagreements between Lloyd George and Kitchener over the supply of munitions (weapons and ammunition) for the army. Lloyd George believed a new department was needed to manage munitions, while Kitchener wanted to keep the current system. Asquith tried to find a compromise.

On 20 April, Asquith gave a speech in Newcastle, saying that reports of ammunition shortages crippling the army were untrue. The press reacted strongly. On 14 May, The Times published a letter claiming that the British failure at the Battle of Aubers Ridge was due to a shortage of high explosive shells. This started the "Shell Crisis."

Newspapers attacked the government and Asquith for being slow. The prime minister's wife, Margot Asquith, believed Lord Northcliffe, the owner of The Times, was behind the attacks. It was later revealed that Sir John French, the British commander, had leaked information about the shell shortage to the press.

Failures in the war and the Shell Crisis led Asquith to believe his Liberal government could not continue. On 15 May, Admiral Fisher resigned due to disagreements with Churchill and the Gallipoli failures. Asquith decided that his government needed to be reformed on a "broad and non-party basis."

First Coalition Government: 1915–1916

Forming a New Government

Asquith formed the First Coalition government, bringing in members from other parties. This meant sacrificing some of his old political friends, like Churchill, who was blamed for the Dardanelles failure, and Haldane, who was wrongly accused of being pro-German. The Conservatives, led by Bonar Law, made these removals a condition for joining the government. Asquith was sad to let Haldane go, calling him his "oldest personal and political friend."

Asquith handled the new appointments carefully. Law became Colonial Secretary, a less important role. Lloyd George took over a new Ministry of Munitions, responsible for war supplies. Arthur Balfour replaced Churchill at the Admiralty. The Liberals still held most of the important Cabinet positions. While many Liberals were upset, the formation of the coalition was seen as a victory for Asquith in keeping his government together.

War Reorganization and Challenges

Asquith reorganized how the war was managed. The most important change was creating the Ministry of Munitions under Lloyd George. This ministry took control of private companies supplying the armed forces. It helped increase the production of weapons and ammunition greatly.

However, criticism of Asquith's leadership continued. Some felt he was too slow and didn't control debates enough. Lloyd George believed the Prime Minister should "lead not follow." Crises and criticism continued to challenge Asquith.

Conscription Debate

The war required a huge number of soldiers. At first, Britain relied on volunteers. Asquith was hesitant to introduce conscription (forced military service) because many Liberals and their Irish and Labour allies were against it. However, volunteer numbers dropped, and more troops were needed for the Western Front.

In July 1915, the National Registration Act was passed, requiring all men aged 18 to 65 to register. This was seen as a step towards conscription. Asquith's slow approach angered his opponents. His wife, Margot Asquith, actively campaigned against conscription, which further hurt his reputation.

By the end of 1915, it was clear that conscription was necessary. Asquith introduced the Military Service Act 1916 in January 1916, which brought in conscription for single men and later for married men. His main opposition came from within his own party, with Sir John Simon resigning over the issue. Asquith managed to pass the bill without breaking up the government, but the long struggle damaged his reputation and party unity.

Easter Rising in Ireland

On Easter Monday 1916, a group of Irish Volunteers and the Irish Citizen Army launched an uprising in Dublin, seizing key buildings. Asquith and his government were slow to react. After quick military trials, many Irish leaders were executed, which caused more anger.

Asquith visited Dublin in May and realized that the system of governance in Ireland was broken. He asked Lloyd George to find a solution. Lloyd George proposed a settlement that would introduce Home Rule after the war, with Ulster excluded. However, Conservatives strongly opposed this plan, and it was abandoned. This episode damaged both Lloyd George's and Asquith's reputations.

War Progress and Personal Loss

Continued Allied failures and heavy losses at the Battle of Loos in late 1915 led to a loss of confidence in the British commander, Sir John French, and Lord Kitchener. Asquith replaced French with Sir Douglas Haig. He also appointed Sir William Robertson as Chief of the Imperial General Staff with more power.

The decision was made to evacuate troops from the Dardanelles in December. Churchill resigned from the Cabinet in protest. More setbacks occurred in the Balkans.

In early 1916, Germany launched a huge offensive at Verdun. In May, the only major naval battle of the war, The Battle of Jutland, took place. Although a strategic success, the British lost more ships, causing dismay. Lord Kitchener was killed when his ship sank on 5 June, which was a great shock.

Asquith offered the vacant War Office to Bonar Law, who declined, and it went to Lloyd George. This was a sign of growing cooperation between Law and Lloyd George, which worried Margot Asquith.

Asquith agreed to inquiries into the Dardanelles and Mesopotamian campaign failures. But these were overshadowed by the huge casualties and limited progress of the Battle of the Somme, which began on 1 July 1916. Then, Asquith suffered a devastating personal loss: his eldest son, Raymond, was killed on 15 September at the Battle of Flers–Courcelette. Asquith was deeply affected and withdrew from public life for a time.

Fall from Power: 1916

The events leading to the collapse of Asquith's coalition government have been studied closely. Many accounts differ, but the main point is that Asquith lost the support of Parliament.

Growing Opposition

A minor issue about the sale of German assets in Nigeria sparked the final crisis. The Conservative leader, Bonar Law, was attacked by Edward Carson, and Lloyd George did not support Law. Margot Asquith immediately sensed danger, believing that powerful figures like Lord Northcliffe, Bonar Law, Carson, and Lloyd George were taking over.

The situation worsened when Lord Lansdowne published a memo suggesting a negotiated peace with Germany. Asquith's critics thought this reflected his own views and that he was using Lansdowne to test the idea.

On 20 November 1916, Lloyd George, Carson, and Law met. They agreed that the government needed to be reorganized. They proposed a small War Council, led by Lloyd George, with full power to manage the war. Asquith would remain Prime Minister but would have only honorary oversight. This plan, with some changes, remained the basis for reforming the government until Asquith's fall.

Lord Northcliffe, a powerful newspaper owner, played a key role. His newspapers, especially The Times, strongly criticized Asquith and supported Lloyd George.

The Final Days

On 25 November, Law, Carson, and Lloyd George drafted a proposal for Asquith. It suggested a "Civilian General Staff" with Lloyd George as chairman and Asquith as president. Asquith rejected this, saying it would weaken his authority.

Lloyd George then proposed an alternative: a War Council of three members, with one as chairman (presumably Lloyd George). Asquith, as Prime Minister, would keep "supreme control." Asquith's reply did not reject it outright but insisted he remain chairman. This was unacceptable to Lloyd George, who told Law that "The life of the country depends on resolute action by you now."

On Sunday, 3 December, Conservative leaders met and demanded that Law tell Asquith the government could not continue. Law met Asquith, who decided that a compromise with Lloyd George was needed. They agreed on a plan where Asquith would have daily oversight and a veto over the War Council's work. They all felt a compromise had been reached.

However, on Monday, 4 December, newspapers, especially Northcliffe's The Times, published details of the compromise and ridiculed Asquith, saying he would be "Prime Minister in name only." Asquith was furious and felt he could not continue unless this impression was corrected. He believed Lloyd George was the source of the leak. Asquith decided to reject the compromise and confront Lloyd George. He offered his government's resignation to the King.

On Tuesday, 5 December, Lloyd George accepted the challenge and resigned. Asquith also received a letter from Arthur Balfour, who supported Lloyd George's plan for a smaller War Council. Asquith met with his senior Liberal colleagues, who were all against compromising with Lloyd George. He also met with Conservative ministers, who said they would not serve in a government without Law and Lloyd George. They also said they would serve under Lloyd George if he could form a stable government.

At 7:00 p.m., Asquith went to Buckingham Palace and resigned as Prime Minister after eight years. That evening, he dined with family and friends, seeming calm. He believed he would soon be back in power.

On Wednesday, 6 December, a conference was held at Buckingham Palace, but no compromise was reached. Asquith, after talking with his Liberal colleagues, refused to serve under Law. At 7:00 p.m., Lloyd George was invited to form a government. Within 24 hours, he had done so, forming a small War Cabinet. On 7 December, he officially became Prime Minister. Most senior Liberals sided with Asquith, but Balfour's acceptance of the Foreign Office made Lloyd George's government possible.

After the Premiership: 1916–1928

Wartime Opposition Leader: 1916–1918

The Asquith family left 10 Downing Street on 9 December. Asquith felt like the biblical character Job, but also noted that other governments were struggling. He was deeply upset by Balfour's actions, especially since he had argued to keep Balfour in the previous government.

Asquith's fall was celebrated by much of the British and Allied press. Attacks on him continued. However, Asquith still controlled the Liberal Party organization. Most Liberal MPs remained loyal to him. On 8 December, Liberal MPs gave Asquith a vote of confidence as party leader.

In Parliament, Asquith offered quiet support to the new government. He made it clear he would not act as an "opposition leader" in the usual sense. However, some of his supporters in the press became frustrated by his reluctance to criticize the government.

Money became a concern for Asquith without his prime ministerial salary. In March 1917, he was offered a high-paying legal position, but he declined. In December 1917, his third son, Arthur, was badly wounded fighting in France and lost a leg.

In May 1918, a letter from Major-General Sir Frederick Maurice appeared in newspapers, accusing Lloyd George and Law of misleading Parliament about army strength. Asquith called for a committee to investigate. Lloyd George offered a judicial inquiry, but Asquith declined. Asquith's speech on the matter was long and lacked force. Lloyd George's reply was powerful, and Asquith's motion was defeated by a large margin. This left Asquith politically weakened.

As the war turned in the Allies' favor in the summer of 1918, Asquith became less politically active.

Decline and Eclipse: 1918–1926

The "Coupon Election" of 1918

Even before the war ended, Lloyd George planned an immediate election. He offered a "Coupon" (a formal endorsement) to candidates who supported his coalition. Asquith called this a "wicked fraud."

Asquith led the Liberal Party into the 1918 election without much enthusiasm. He hoped for 100 Liberal MPs to be elected. He started by attacking the Conservatives but ended up criticizing the government's demands.

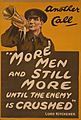

Asquith was one of five people given a free pass by the Coalition, but the local Unionist Association in East Fife put up a candidate against him. Asquith spent little time campaigning in his own seat, assuming it was safe. Posters during the campaign asked: "Asquith nearly lost you the War. Are you going to let him spoil the Peace?"

On 14 December, Lloyd George's coalition won by a landslide. Asquith and every other former Liberal Cabinet minister lost their seats. Margot Asquith was surprised but said, "Thank God!" Asquith saw it as a "crippling" personal humiliation.

Out of Parliament and Return to Paisley

Asquith remained leader of the Liberal Party, even though he was no longer in Parliament. He was very unpopular at first. Around 29 Liberals who did not support the coalition were elected, forming a "Free Liberal" group, also known as the "Wee Frees." They accepted Asquith's leadership but there was discontent.

In April 1919, Asquith gave his first public speech since the election. He was disappointed by the terms of the Treaty of Versailles but did not strongly oppose it. In late 1919, he received war medals, which the War Office had initially intended only for Lloyd George.

In January 1920, an opportunity arose for Asquith to return to Parliament in a by-election in Paisley, Scotland. He was chosen as the Liberal candidate after some debate. Asquith was hesitant but grew more confident during the campaign. He focused his campaign on criticizing the Coalition government and calling for a less harsh approach to Germany and the Irish War of Independence.

Asquith won the election by over 2,000 votes, a surprising victory. He was greeted by cheering crowds in Glasgow and London. However, he received a cold welcome in Parliament from Coalition politicians.

Leader of the Opposition: 1920–1922

Asquith's return to Parliament was a brief moment of hope for the Liberals. His political influence continued to decline. He faced increasing financial concerns due to Margot's spending and his lack of a prime ministerial salary. They moved to a smaller house in London.

Criticism of Asquith's weak leadership continued. He spoke more often in the House of Commons and around the country, but the quality of his contributions was questioned. He maintained friendly relations with Lloyd George, but Margot openly disliked him.

Asquith had previously accepted that the next government might be a Liberal-Labour coalition, but Labour distanced themselves due to his policies. By late 1921, Asquith's leadership was still under attack from within his own party. He fiercely opposed the "hellish policy of reprisals" in Ireland.

In October 1922, Lloyd George's government fell when his Conservative partners withdrew their support. Bonar Law formed a purely Conservative government. In the 1922 general election, Asquith ceased to be Leader of the Opposition because Labour elected more MPs than the two Liberal factions combined. Asquith narrowly won his seat in Paisley but was disappointed by the overall Liberal results.

Liberal Reunion and the 1923 Election

In March 1923, there were calls for reunion among Liberal MPs. However, senior Asquithian Liberals opposed it, mainly due to their dislike of Lloyd George. Asquith was superficially friendly with Lloyd George but did not include him in the Shadow Cabinet. He believed that Lloyd George's faction was weakening, so he could wait.

The political situation changed when the new Prime Minister, Stanley Baldwin, supported Protection (tariffs on imports). Lloyd George, who supported Free Trade, had to formally accept Asquith's leadership. Asquith and Lloyd George agreed to work together, and Lloyd George even campaigned for Asquith in Paisley.

Asquith led an energetic national campaign on free trade in 1923. He did not expect to win a majority but hoped to become Leader of the Opposition again. The election in December 1923 resulted in a hung Parliament. The Liberals gained seats but were still in third place.

Putting Labour in Power

The Liberals decided not to support a Conservative government. Asquith believed that if a Labour government was to be tried, it should be under safe conditions. He thought Labour would soon be discredited, and the Liberal Party would revive.

The Liberals supported Britain's first ever minority Labour government under Ramsay MacDonald. Asquith believed MacDonald's government was weak. However, relations with Labour soon became tense, as Liberal MPs were angered by Labour's hostility towards them.

Asquith played a significant role in forcing MacDonald out of power later that year over the Campbell Case (a controversy about withdrawing a prosecution against a newspaper). Asquith's motion for a select committee passed, leading MacDonald to call a General Election.

The 1924 Election and Peerage

The 1924 election was intended by MacDonald to weaken the Liberals, and it succeeded. Asquith was widely expected to lose his seat in Paisley and did so by over 2,000 votes. He received 46.5% of the vote in his final parliamentary election.

This was a political disaster for Asquith and the Liberal Party. Baldwin won a landslide victory, and Labour became the main opposition party. The Liberal vote collapsed.

The 1924 election was Asquith's last parliamentary campaign. The King offered him a peerage (a title that would make him a member of the House of Lords). Asquith accepted in January 1925, choosing the title "Earl of Oxford." However, the College of Heralds insisted he add "and Asquith" to the title after protests from the Harley family, who had previously held the title. He was known as "Lord Oxford" but never enjoyed the House of Lords.

In 1925, he stood for the Chancellorship of Oxford University. Despite being highly qualified, he lost the election. He was very disappointed. In May 1925, Baldwin awarded him the Order of the Garter, a high honor.

Resignation from Leadership

Difficulties continued with Lloyd George over the Liberal Party leadership and funds. Lloyd George began his own campaign for land ownership reform, ignoring Asquith. At a meeting in November 1925, several leading Liberals urged Asquith to confront Lloyd George about money. Asquith suffered a stroke in June 1926, which put him out of action for three months.

Asquith finally resigned as Liberal leader on 15 October 1926.

Final Years and Legacy: 1926–1928

Asquith spent his retirement reading, writing, playing golf, traveling, and meeting friends. He had developed an interest in modern art.

His health remained fair until near the end, but he faced increasing financial worries. He suffered a second stroke in January 1927, which affected his left leg and made him use a wheelchair for a while. His last visit was to see a friend in Norfolk. On his return home in autumn 1927, he could no longer get out of his car or go upstairs. He suffered a third stroke at the end of 1927. His last months were difficult, and he became increasingly confused.

Asquith died at his home, The Wharf, on 15 February 1928, at the age of 75. He was buried simply in the churchyard of All Saints' at Sutton Courtenay. A blue plaque marks his former home in London, and a memorial tablet was placed in Westminster Abbey.

Descendants

Asquith had five children with his first wife, Helen, and two surviving children with his second wife, Margot.

- His eldest son, Raymond, was killed in the Somme in 1916.

- His second son, Herbert (1881–1947), became a writer and poet.

- His third son, Arthur (1883–1939), was a soldier and businessman.

- His only daughter by his first wife, Violet (1887–1969), became a respected writer and a life peeress.

- His fourth son, Cyril (1890–1954), became a senior judge.

- His two children with Margot were Elizabeth (1897–1945), a writer, and Anthony Asquith (1902–1968), a film-maker.

Among his living descendants are his great-granddaughter, the actress Helena Bonham Carter (born 1966), and two great-grandsons, Dominic Asquith, a former British High Commissioner to India, and Raymond Asquith, 3rd Earl of Oxford and Asquith, who inherited Asquith's title. Another British actress, Anna Chancellor (born 1965), is Asquith's great-great-granddaughter.

How Asquith is Remembered

Asquith's reputation is greatly shaped by his fall from power during World War I. Many historians believe that David Lloyd George took over because people wanted a more energetic leader to win the war. Asquith's calm approach, his tendency to "wait and see," and his dislike of the press contributed to the feeling that he couldn't handle the demands of total war.

However, some historians argue that Asquith's achievements were significant. He led Britain into the war with very few Cabinet resignations, showing his skill in uniting the country. Lord Birkenhead, a contemporary, praised Asquith for bringing Britain united into the war.

Asquith's governments made many key decisions during the war:

- The decision to join the war.

- Sending the British Expeditionary Force.

- Raising a large volunteer army.

- Starting and ending the Gallipoli Campaign.

- Forming a coalition government.

- Mobilizing industry.

- Introducing conscription.

Asquith's fall also marked the end of the Liberal Party as one of Britain's two major political parties. After 1922, the Liberals rarely held power again. Some historians believe Asquith bears some responsibility for this decline.

Despite his weaknesses as a war leader, Asquith's achievements in peacetime are highly regarded. His government passed many important social and political reforms, laying the groundwork for the modern welfare state. He also worked hard to resolve the Irish question, and his efforts contributed to the later settlement.

Asquith was known for his powerful speaking skills in Parliament. He was praised for his clear arguments and authoritative presence. His ability to lead and manage a talented but diverse group of politicians for a long time is considered one of his major achievements. Historians conclude that based on his achievements from 1908 to 1914, Asquith ranks among the greatest British statesmen.

Images for kids

-

Campbell-Bannerman, Liberal leader from 1899

-

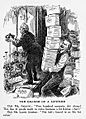

Asquith as Chancellor of the Exchequer, in the House of Commons

-

The British Empire in 1910

-

Asquith visits the front during the Battle of the Somme, 1916

-

Asquith's great-granddaughter, the actress Helena Bonham Carter

-

Memorial to Asquith, Westminster Abbey

-

Blue plaque, 20 Cavendish Square, London

See also

In Spanish: Herbert Henry Asquith para niños

In Spanish: Herbert Henry Asquith para niños