History of African Americans in Baltimore facts for kids

The history of African Americans in Baltimore goes back to the 1600s. This was when the first African slaves were brought to Maryland. For most of its history, Baltimore had more white people. But in the 1970s, it became a city with more Black residents.

By the 2010 Census, African Americans made up 63% of Baltimore's population. Baltimore has been a majority-Black city for many years. It has the 5th largest Black population of any city in the United States. Because of this, African Americans have greatly shaped the city's culture, way of speaking, history, politics, and music.

Unlike many Northern cities where Black populations grew mostly during the Great Migration, Baltimore has a long history with its Black community. It was home to the largest group of free Black people about 50 years before the Emancipation Proclamation. Between 1910 and 1970, thousands of African Americans moved to Baltimore from the South and Appalachian areas. This made Baltimore the second northernmost city with a Black majority, after Detroit.

The African-American community in Baltimore is mostly found in West Baltimore and East Baltimore. This pattern is sometimes called "The Black Butterfly." White Americans in Central and Southeast Baltimore are sometimes called "The White L."

Contents

How Baltimore's Population Changed

| African-American population in Baltimore | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Percentage | |

| 1790 | 11.7% | |

| 1800 | 21.2% | |

| 1810 | 22.2% | |

| 1820 | 23.4% | |

| 1830 | 23.5% | |

| 1840 | 20.7% | |

| 1850 | 16.8% | |

| 1860 | 13.1% | |

| 1870 | 14.8% | |

| 1880 | 16.2% | |

| 1890 | 15.4% | |

| 1900 | 15.6% | |

| 1910 | 15.2% | |

| 1920 | 14.8% | |

| 1930 | 17.7% | |

| 1940 | 19.3% | |

| 1950 | 23.8% | |

| 1960 | 34.7% | |

| 1970 | 46.4% | |

| 1980 | 54.8% | |

| 1990 | 59.2% | |

| 2000 | 64.3% | |

| 2010 | 63.7% | |

In 1790, African Americans made up 11.7% of Baltimore's population. This was the first census in U.S. history. From 1800 to 1840, about one-fifth to one-quarter of Baltimore's people were African American. The percentage dropped in the 1850s and was lowest in 1860 at 13%.

Between the 1860s and 1920s, Baltimore's African-American population stayed between 13-16%. It started to grow again in the 1930s and 1940s during the Great Migration. During this time, thousands of African Americans moved to Baltimore from the Southern United States looking for better lives and jobs. They also sought freedom from unfair laws and racism. Many came from states like Alabama, Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, and North Carolina.

By 1960, Baltimore had 325,589 African-American residents, making up 34.7% of the city. By 1970, this number grew to 46.4%, almost half of the population. In 1980, African Americans became the majority for the first time, with 431,151 residents, or 54.8% of the population. By 1990, this increased to 59.2%.

In 2010, there were 395,781 African Americans in Baltimore, making up 63.7% of the population. In 2017, this was estimated to be 389,222, or 62.8%. Baltimore's African-American population has been decreasing since 1993.

Key Moments in History

Early Days: 1600s to 1800s

The first Black people came to what is now Baltimore in 1634. They arrived with English settlers. These included two mixed-race servants, Mathias de Sousa and Francisco, and another servant named John Prince.

From the late 1700s into the 1820s, Baltimore was a fast-growing city. Many former slaves moved there from nearby areas. Slavery in Maryland slowly decreased after the 1810s. This was because the state's economy changed from large farms. Also, new religious ideas and laws made it easier for slave owners to free enslaved people.

Baltimore had a growing number of free Black people. They often worked alongside enslaved people who were close to being free. Jobs were available in shipyards, and there was little conflict with white workers. Even though many free Black people were poor, Baltimore was seen as a "city of refuge." Both enslaved and free Black people found more freedom there than in other cities.

Churches, schools, and community groups helped Black people. However, after 1840, many German and Irish immigrants came to Baltimore. This made it harder for free Black people to find jobs, and many became poorer.

Slave owners in Baltimore sometimes promised freedom after a certain number of years. This was to encourage enslaved people to work hard. The number of enslaved people in the city dropped a lot between 1850 and 1860. This showed that slavery was no longer very profitable in Baltimore.

Civil War and Beyond: 1860s

On the eve of the Civil War, Baltimore had the largest community of free Black people in the United States. About 15 schools for Black children were open. These included Sunday schools run by Methodists, Presbyterians, and Quakers, plus private academies. All Black schools paid for themselves. They did not get money from the state or local government. White people in Baltimore generally did not want Black people to be educated. They still taxed Black property owners to support schools that Black children could not attend.

The new Maryland state constitution of 1864 ended slavery. It also said that all children, including Black children, should be educated. The Baltimore Association for the Moral and Educational Improvement of the Colored People started schools for Black people. The public school system later took these over. But then, in 1867, when Democrats took control of the city, they limited education for Black people.

This created an unfair system. White students were prepared for full citizenship, while education for Black students was used to keep them in a lower position. Black leaders pushed for "colored schools" to be staffed only by Black teachers. From 1867 to 1900, Black schools grew from 10 to 27. Enrollment went from 901 to 9,383 students.

20th Century Changes

In 1910, Baltimore lawyer Milton Dashiell pushed for a law to stop African Americans from moving into certain neighborhoods. This law would recognize blocks as mostly white or mostly Black. It would prevent people from moving into homes where they would be a minority. The Baltimore Council passed this law, and it became official on December 20, 1910. This Baltimore segregation law was the first of its kind in the United States. Many other Southern cities later passed similar laws. However, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled against these laws in 1917.

By 1968, Baltimore had a local chapter of the Black Panther Party. The Black Panther Party faced challenges in Baltimore in the late 1960s and early 1970s. This was due to monitoring and pressure from the FBI and the Baltimore City Police Department. Between 1968 and 1972, the Baltimore Black Panthers used different buildings for meetings and activities. They organized community programs like free breakfast and lunch. They also held many protests.

21st Century Events

On April 12, 2015, there was great anger over the Death of Freddie Gray. He died while in the care of Baltimore Police Department officers. This led to the 2015 Baltimore protests. Freddie Gray, a West Baltimore resident, died on April 19, 2015, after being in a coma for a week. He had been taken into custody after running from police. Gray suffered spinal injuries while with the police. Some people said his injuries were accidental, while others said they were due to police brutality.

Protests were peaceful at first, with thousands gathering at City Hall. But after Gray's funeral on April 27, protests turned violent. People burned police cars and buildings and damaged stores. The Governor of Maryland, Larry Hogan, sent in the National Guard and set a curfew. Six police officers were charged with crimes related to Gray's death.

Culture and Community

Baltimore's Unique Way of Speaking

Linguists say that the accent of African Americans in Baltimore is different from the "hon" accent. The "hon" accent is often shown in media as being spoken by white working-class Baltimoreans. White working-class families who moved out of Baltimore city created local ways of speaking that became known as the "Baltimore accent."

However, Black Baltimoreans have their own special accent. For example, many Black speakers say Baltimore more like "Baldamore," instead of "Bawlmer." Other features include saying words like "carry" and "parents" more like "curry" or "purrents." Also, "dog" is often pronounced like "dug," and "frog" like "frug." The accent of African-American Baltimoreans also shares features with African American English.

LGBT Community in Baltimore

In 2001, The Portal was created as a community center for LGBT African Americans. This center, which is now closed, was meant to be a safe place for LGBT people of color. It offered health and safety information, including AIDS awareness. The Portal aimed to help "stronger, more effective same gender loving communities of color."

The Unity Fellowship Church of Baltimore serves LGBT African-American Christians and other LGBT Christians of color. It is part of a national movement for LGBT Christians of color. Baltimore's Unity Fellowship Church has about 150 members. While some homophobia exists in the African-American community, most African Americans in Maryland support same-sex marriage.

Club Bunns, a gay club near Lexington Market that attracted gay Black men, closed in February 2019 after 30 years.

Books and Publishing

In the 1930s and 1940s, the Communist Party of Maryland ran a bookstore called the Frederick Douglass Bookshop. The FBI often watched this store. The FBI called it a "Communist Party literature distribution point in the Negro section of [West] Baltimore." For ten years, this Black communist bookstore was a main meeting place for Baltimore's Communist Party.

William Paul Coates (father of Ta-Nehisi Coates) started Black Classic Press in 1978 in Baltimore. He began working from his basement. This company is one of the oldest independently owned Black publishers in the United States. Black Classic Press has published books by famous authors. It has also reissued important works by writers like W. E. B. Du Bois.

News and Media

The Baltimore Afro-American, also known as The Afro, is a weekly newspaper in Baltimore. It is the main newspaper of the Afro-American chain. It is the longest-running African-American family-owned newspaper in the United States. John H. Murphy Sr. started it in 1892.

Museums to Visit

The Reginald F. Lewis Museum of Maryland African American History & Culture is a top place to learn about the lives of African American Marylanders. The museum collects, saves, explains, and shows the many contributions of African American Marylanders. It has over 11,000 documents and objects. The museum is 82,000 square feet and is a short walk from Baltimore's Inner Harbor. It opened in 2005 and is connected to the Smithsonian Institution. It was named after Reginald F. Lewis, the first African American to build a company worth a billion dollars.

The National Great Blacks In Wax Museum is a wax museum in the Oliver neighborhood. It features important African-American historical figures. It started in 1983 in a downtown storefront. The museum is now in a renovated firehouse and other buildings. It has almost 30,000 square feet of space. The exhibits include over 100 wax figures. There is also a full model slave ship exhibit that shows the 400-year history of the Atlantic Slave Trade. Another exhibit shows the role of young people in history. A Maryland room highlights contributions by notable Marylanders.

Theater and Movies

The Royal Theatre, located on Pennsylvania Avenue, first opened in 1922 as the Black-owned Douglass Theatre. It was the most famous theater along West Baltimore's Pennsylvania Avenue. It was one of five such theaters for Black entertainment in big cities. Its sister theaters included the Apollo in Harlem and the Howard Theatre in Washington, D.C.. As white families moved out of Old West Baltimore in the 1960s and 1970s, the area declined. In 1971, the Royal Theater was torn down.

The topic of young African-American dirt bike riders in Baltimore has been featured in two documentaries and one fictional film. 12 O'Clock Boyz (2001) was the first film to show the dirt bike scene. In 2013, another documentary called 12 O'Clock Boys focused on the same topic. The movie Charm City Kings, starring Teyonah Parris and Meek Mill, is a fictional film based on the 2013 documentary.

Religious Life

Most African Americans in Baltimore are Christians. They are usually either Protestant or Catholic. Smaller numbers belong to other Christian groups like Mormonism or Jehovah's Witnesses. Some African Americans follow other religions such as Islam, Judaism, or Buddhism. Some are atheist or agnostic. A growing number of young Black people, especially young Black women, are exploring spiritual practices rooted in traditional African religions.

Christian Faiths

Protestant Churches

The Orchard Street United Methodist Church is the oldest building in Baltimore built by African Americans. Truman Le Pratt, a former slave from the West Indies, founded the church in 1825. The building now holds offices for the National Urban League.

Catholic Churches

Baltimore has a strong and well-known African-American Roman Catholic community. St. Francis Xavier Church in the Oliver neighborhood says it was the "first Catholic church in the United States for an all-colored congregation." It was started in 1863. The church attracted the Black elite of Baltimore. Its founders were Black Haitian refugees and the Sulpician Fathers. The second Black parish in Baltimore was St. Monica's, started in 1883. By the early 1900s, Baltimore had two more Black Catholic parishes: St. Peter Claver and St. Barnabas.

Jewish Faith

Baltimore has a small group of African-American Jews. Historically, there were strong ties between African-American and Jewish-American communities in Baltimore. Many white Jewish Baltimoreans supported the civil rights movement. However, there have been tensions. For example, in 2010, a Black teenager was beaten by white members of an Orthodox Jewish community patrol group. In mostly white Jewish spaces, white Jews are sometimes accepted easily. But Black Jews and other Jews of color may face questions about their identity.

Congregation Beth HaShem on Collington Avenue was started as a synagogue for African-American Jews. Rabbi George McDaniel, who founded Beth HaShem, says that white Ashkenazi Jews are not questioned about being Jewish because they are white. But "If you're black and you say I'm Jewish, now you have to prove your Jewishness." Black Jews in Baltimore can face racism for being Black and antisemitism for being Jewish. Some Black Jewish Baltimoreans have reported being called slurs by non-Black Jews. They have also been bothered by non-Jews for wearing a kippah (a small cap).

Neighborhoods with Many African Americans

- Ashburton

- Barclay

- Belair-Edison

- Berea

- Better Waverly

- Broadway East

- Brooklyn

- Cedonia

- Cherry Hill

- Coldstream-Homestead-Montebello

- Coppin Heights

- East Baltimore Midway

- Edmondson Village

- Ednor Gardens-Lakeside

- Ellwood Park

- Glen, Baltimore

- Govans, Baltimore

- Greenmount West

- Gwynn's Falls

- Hillen, Baltimore

- Lakeland

- Langston Hughes

- Liberty Square

- Loch Raven

- Johnston Square

- Jonestown

- McElderry Park

- Middle East

- Mid-Govans

- Mondawmin

- Mosher

- Northwood

- Oliver

- Pen Lucy

- Pimlico

- Ramblewood

- Rosemont

- Sandtown-Winchester

- Stonewood-Pentwood-Winston

- Upton

- Washington Hill

- Waverly

- Westgate

- West Hills

- Westport

- Wilson Park

- Woodbourne Heights

Famous African Americans from Baltimore

Gallery

- Victorine Q. Adams, the first African-American woman to serve on the Baltimore City Council.

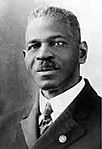

- Clarence H. Burns, a Democratic politician and the first African American mayor of Baltimore in 1987.

- Cab Calloway, a jazz singer, dancer, and bandleader.

- Kevin Clash, a puppeteer, director, and producer. He created characters like Elmo.

- Carl Dix, a founding member of the Revolutionary Communist Party, USA (RCP).

- Sheila Dixon, served as the 48th mayor of Baltimore.

- Bea Gaddy, a Baltimore City Council member and a leader for the poor and homeless. She was known as the "Mother Teresa of Baltimore."

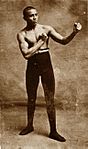

- Joe Gans, a professional boxer known as the "Old Master." He was the first African-American world boxing champion of the 1900s.

- L. S. Alexander Gumby, an archivist and historian. His collection of 300 scrapbooks about African-American history is at Columbia University.

- Ken Harris, a Democratic politician who served on the Baltimore City Council.

- William Ashbie Hawkins, one of Baltimore's first African American lawyers.

- Billie Holiday, a jazz singer whose career lasted almost 30 years. She greatly influenced jazz and pop singing.

- Yaphet Kotto, an actor known for many film and TV roles, including Lieutenant Al Giardello on Homicide: Life on the Street.

- Reginald Lewis, a businessman who was one of the richest African-American men in the 1980s. He was the first African American to build a billion-dollar company.

- Lillie Mae Carroll Jackson, a civil rights activist who helped organize the Baltimore branch of the NAACP.

- Angel McCoughtry, a professional basketball player for the Atlanta Dream (WNBA).

- DeRay Mckesson, a Black Lives Matter activist, podcaster, and former school administrator.

- Enolia McMillan, an African American educator, civil rights activist, and community leader. She was the first female national president of the NAACP.

- Sharon Green Middleton, a Democratic politician who served as the acting President of the Baltimore City Council.

- Abbie Mitchell, a soprano opera singer known for singing "Clara" in the first production of George Gershwin's Porgy and Bess.

- Clarence Mitchell Jr., a civil rights activist who was the main lobbyist for the NAACP for almost 30 years.

- Clarence Mitchell III, a politician who served in the Maryland Senate and the Maryland House of Delegates.

- Keiffer Mitchell Jr., a politician who served in the Maryland House of Delegates and the Baltimore City Council.

- Parren Mitchell, the first African American elected to Congress from Maryland.

- Nick J. Mosby, a politician who served in the Maryland House of Delegates and the Baltimore City Council.

- John H. Murphy Sr., an African-American newspaper publisher, born into slavery. He is best known for starting the Baltimore Afro-American newspaper.

- Pauli Murray, a civil rights activist who became a lawyer, women's rights activist, author, and the first African-American woman to be ordained as an Episcopal priest.

- Felicia "Snoop" Pearson, an actress and author who played "Snoop" on The Wire.

- Catherine Pugh, a Democratic politician, who served as the 50th mayor of Baltimore.

- Stephanie Rawlings-Blake, a politician and attorney who served as the 49th Mayor of Baltimore from 2010 to 2016.

- Oscar Requer, a former detective of the Baltimore Police Department.

- Gloria Richardson, the leader of the Cambridge Movement, a civil rights struggle in the early 1960s in Cambridge, Maryland.

- April Ryan, a journalist and author who has been a White House correspondent since 1997.

- Kurt Schmoke, a politician and lawyer who served as the 46th mayor of Baltimore. He was the first African American to be elected mayor.

- Brandon Scott, the current president of the Baltimore City Council.

- Serpentwithfeet, an experimental musician from Baltimore.

- Tupac Shakur, a rapper, writer, and actor. Many consider him one of the greatest rappers of all time.

- André De Shields, an actor, singer, director, dancer, and professor.

- Breanna Sinclairé, a transgender singer. She was the first transgender woman to sing the American national anthem at a professional sporting event.

- Jada Pinkett Smith, an actress, singer-songwriter, and businesswoman. She is married to Will Smith.

- Rain Pryor, an actress and comedian. She is the daughter of the late comedian Richard Pryor.

- Sonja Sohn, an actress and director best known for her role as Detective Kima Greggs on the HBO drama The Wire.

- Carl Stokes, a politician who represents the 12th district on the Baltimore City Council.

- Melvin L. Stukes, a politician who represented the 44th legislative district in the Maryland House of Delegates.

- Mary L. Washington, a Democratic politician elected in 2018 to the Maryland Senate.

- William A. White, an American-born Nova Scotian who was the first Black officer in the British army.

- Deniece Williams, a Grammy-winning singer, songwriter, and producer.

- William Llewellyn Wilson, a conductor, musician, and educator. He was the first conductor of the first African American symphony in Baltimore.

- Y-Love, a Jewish hip-hop artist whose lyrics cover social, political, and religious themes.

- Jack Young, a Democratic politician and the current mayor of Baltimore.

| Aurelia Browder |

| Nannie Helen Burroughs |

| Michelle Alexander |