History of China–United States relations facts for kids

The history of how the United States and China have gotten along is a long and interesting story. This article looks at their relationship from the time of China's Qing dynasty (an old empire) and the early Republic of China (a new country). For how the two countries have gotten along since 1949, when the People's Republic of China was formed, see China–United States relations.

Historians have described how American feelings toward China changed over time. In the 18th century, there was "respect." From 1840 to 1905, it was more like "contempt." Then, from 1905 to 1937, it became "benevolence," followed by "admiration" from 1937 to 1944. After that, from 1944 to 1949, feelings shifted to "disenchantment," and after 1949, it was "hostility." Later, in the 1970s, there was "reawakened curiosity" and "guileless fascination," but by the 1980s, it became "renewed skepticism."

Contents

The Qing Dynasty and the United States

China |

United States |

|---|---|

The United States, which had just become independent, sent its first representatives to Guangzhou (Canton) as early as 1784. However, Chinese officials did not officially recognize them as government representatives. The first time the two countries formally recognized each other under international law was in 1844. This happened when they negotiated and signed the Treaty of Wanghia.

Early Trade Between Nations

Early trade involved silver, gold, ginseng, and furs going to China. From China, the U.S. imported tea, cotton, silk, lacquerware, porcelain, and fancy furniture. The very first American ship to trade with China was the Empress of China in 1784.

American merchants, many from Salem, Massachusetts, became very rich from this trade. They were some of America's first millionaires. Chinese artists and craftspeople noticed what Americans liked. They started making goods especially for export, often adding American or European designs.

American Missionaries in China

The first American missionary in China was Elijah Coleman Bridgman. He arrived in 1830. He learned the Chinese language and wrote a history of the United States in Chinese. In 1832, he started an English newspaper called The Chinese Repository. This paper became a main source of information about Chinese culture and politics.

American missionaries were very important for China's growth. They taught Chinese people Western science, how to think critically, sports, and law. They also started China's first universities and hospitals. Many of these places are still top institutions in China today.

Women missionaries also played a special role. They used physical education and sports to promote healthy living. They showed how poor people could do well and helped expand what women could do.

During the Boxer Rebellion (1899–1901), many Christian missions were burned. Thousands of Chinese Christians were killed, and American missionaries barely escaped with their lives.

Caleb Cushing and Treaties

After Britain won the First Opium War in 1842, the Treaty of Nanking opened five Chinese ports to British trade. In 1843, U.S. President John Tyler sent Caleb Cushing as a special representative. Cushing arrived in Macau in 1844 with four Navy warships and many gifts. These gifts included revolvers, telescopes, and an encyclopedia.

Cushing wanted to impress the Chinese court and gain access to the five ports. He warned that not receiving an envoy was an insult. He even threatened to go directly to the Emperor. The Emperor eventually sent someone to negotiate. This led to the signing of the Treaty of Wanghia on July 3, 1844.

This treaty gave the U.S. "most favored nation" status. This meant Americans received the same trading benefits as other countries. Cushing also made sure Americans had extraterritoriality. This meant that if Americans committed crimes in China, they would be tried by Western judges, not Chinese ones.

After this, American trade with China grew fast. High-speed clipper ships carried valuable goods like ginseng and silk. American Protestant missionaries also began to arrive. Many Chinese people did not like foreigners, but some supported the missionaries and businessmen. Foreign trade suffered during the Taiping Rebellion (1850–1864), which caused millions of Chinese deaths.

During the Second Opium War, American and Chinese forces fought briefly in 1856. This was the Battle of the Barrier Forts. After China's defeat in 1860, the Treaty of Tientsin was signed. This treaty allowed the U.S., Britain, France, and Russia to have offices in Beijing.

Taiwan and American Interest

Some Americans thought the U.S. should take Taiwan from China, but Washington did not support this idea. Sometimes, local people in Taiwan attacked Western sailors whose ships had crashed. In 1867, during the Rover incident, Taiwanese natives killed shipwrecked American sailors. They also defeated an American military group sent to get revenge.

Chinese Immigration and Exclusion

In 1868, the Chinese government sent an American, Anson Burlingame, as their representative to the U.S. Burlingame traveled the U.S. to gain support for fair treatment of China and Chinese immigrants. The Burlingame Treaty of 1868 supported these ideas. In 1871, the Chinese Educational Mission brought 120 Chinese boys to study in the U.S. They were led by Yung Wing, the first Chinese student to graduate from an American college.

In the 1850s and 1860s, many Chinese people came to the U.S. because of the California Gold Rush and to build the transcontinental railroad. This caused some Americans to dislike them. Chinese people were often forced out of the mines. Most then created Chinatowns in cities like San Francisco. They often worked in laundries and cleaning.

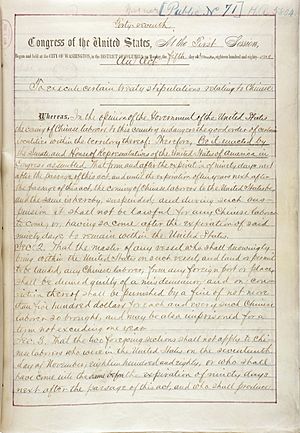

Anti-Chinese feelings grew strong. In 1882, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act. This law stopped Chinese skilled and unskilled workers from entering the U.S. for ten years. It was the first major limit on free immigration in U.S. history. The ban was renewed many times and lasted for over 60 years.

The Search for the China Market

The American China Development Company was started in 1895 by rich businessmen like J. P. Morgan and Andrew Carnegie. They wanted to help China industrialize quickly. They began building a railroad to connect central and southern China. However, they only finished 30 miles of track. Americans soon became disappointed and sold their shares. Overall, the American dream of getting rich by investing in China or selling to millions of Chinese people often failed. Only a few companies, like Standard Oil selling kerosene for lamps, made a profit.

The Boxer Rebellion

In 1899, a group of Chinese nationalists called the Society of Right and Harmonious Fists started a violent revolt. Westerners called it the Boxer Rebellion. This uprising was against foreign influence in China's trade, politics, religion, and technology. It lasted from November 1899 to September 1901, during the last years of the Qing dynasty.

The rebellion began as an anti-foreign movement by peasants in northern China. They were angry because Westerners were taking land, gaining special rights, and protecting criminals who became Catholic. The Boxers attacked foreigners who were building railroads and Christians. In June 1900, the Boxers entered Beijing and attacked the area around the foreign offices. On June 21, the Empress Dowager Cixi declared war on all Western powers.

Diplomats, foreign civilians, soldiers, and Chinese Christians were trapped for 55 days. Eight countries—Austria-Hungary, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Russia, Britain, and the United States—formed an alliance. They sent troops to help. The first group of 2,000 troops, including 116 Americans, was pushed back by the Boxers. A larger Allied force then succeeded.

The United States played a smaller but important role in stopping the Boxer Rebellion. This was because they had warships in the Philippines. In 1900-1901, American forces were part of the Allied occupation of Beijing. American commander Colonel Adna Chaffee worked with Chinese officials to improve public health and police services.

The foreign powers made China pay them for the damages through the Boxer Protocol. In 1908, U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt used America's share of these funds for educational exchanges with China. This led to thousands of Chinese students studying in the United States over the next 40 years. These funds also helped establish schools in China, like Tsinghua College in Beijing.

With national attention on the Boxers, American Protestants made missions to China a high priority. They supported many missionaries and opened universities, medical schools, and other schools in China. While not many Chinese converted to Christianity, the educational impact was huge.

The Open Door Policy

In the 1890s, major world powers like France, Britain, Germany, Japan, and Russia started claiming special areas of influence in China. China was then ruled by the Qing dynasty. The United States wanted these ideas to be dropped so that all nations could trade equally.

In 1899, U.S. Secretary of State John Hay sent letters to these nations. He asked them to promise that China's land and government would remain whole. He also asked them not to stop free trade in their claimed areas. The other powers did not fully agree but said they would if others did. Hay took this as acceptance of his idea, which became known as the Open Door Policy.

While respected by many, Russia and Japan ignored the Open Door Policy when they moved into Manchuria. The U.S. protested Russia's actions. Japan and Russia then fought the Russo-Japanese War in 1904. The U.S. helped to arrange a peace agreement.

Other Exchanges

In 1872, the Qing dynasty sent 120 students to the U.S. This was China's first official educational mission.

The Republic of China and the United States

China |

United States |

|---|---|

From 1911 to 1937

After the Xinhai Revolution in 1911, Washington recognized the new Government of the Chinese Republic as China's only legal government. However, in reality, many powerful regional warlords controlled different parts of China. The central government mostly handled foreign policy.

In 1915, Japan made a set of secret demands to Yuan Shikai, China's president. These "Twenty-One Demands" would greatly increase Japan's control over China. Japan wanted to keep German lands it had taken in World War I. It also wanted more power in Manchuria and South Mongolia. The most extreme demands would have made China a protectorate of Japan. This would have reduced Western influence.

Japan was in a strong position because Western powers were busy fighting Germany. Beijing made the demands public and asked Washington and London for help. They pressured Tokyo, and in 1916, Japan dropped its most extreme demands. Japan gained a little in China but lost a lot of trust from the U.S. and Britain.

The U.S. State Department believed that a "strong and independent China" was important for American interests in Asia. They felt China deserved sympathy and that ignoring it could lead to losing influence in the Far East.

In 1922, the Nine-Power Treaty was signed by Washington, Beijing, Tokyo, London, and others. This treaty clearly protected China.

Frank Kellogg, the U.S. Secretary of State (1925–1929), favored China. He worked to protect China from threats from Japan. A key goal for China was to control its own tariff rates, which Western powers had set very low. Another goal was to end extraterritoriality, where Westerners controlled cities like Shanghai. Kellogg successfully negotiated tariff reform with China. This helped the Kuomintang (KMT) government gain more power and get rid of the unequal treaties. China was reunified under the KMT government in 1928. With American help, China achieved some of its diplomatic goals between 1928 and 1931.

Starting in the 1870s, American missionaries began building schools in China. They found that Chinese people wanted Western education much more than Christianity. Programs were set up to help Chinese students study in American colleges. Pearl S. Buck, an American who grew up in China, wrote popular books and gave lectures. Her work helped Americans support Chinese peasants. President Woodrow Wilson, who had former students who were missionaries in China, strongly supported their work.

World War II and China

When the Second Sino-Japanese War began in 1937, the United States, led by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, started sending a lot of military and economic aid to the Republic of China (ROC). American laws called Neutrality Acts usually stopped aid to countries at war. However, because Japan had not officially declared war on China, Roosevelt said that a state of war did not exist. This allowed him to send aid to Chiang Kai-shek.

American public sympathy for China grew. Missionaries, writers like Pearl S. Buck, and Time Magazine reported on Japan's harsh actions in China. Relations between Japan and the U.S. worsened after the USS Panay incident. During the bombing of Nanjing, a U.S. Navy gunboat was accidentally sunk by Japanese planes. Roosevelt demanded an apology and payment, which he received, but relations continued to get worse. Most Americans strongly supported China and criticized Japan.

The United States strongly supported China starting in 1937. It warned Japan to leave China. American money and military help began to flow. Claire Lee Chennault led the 1st American Volunteer Group, known as the Flying Tigers. These American pilots flew American planes painted with the Chinese flag to attack the Japanese.

In 1941, the United States cut off Japan's main oil supplies to try and force Japan to make peace with China. Instead, Japan attacked American, British, and Dutch lands in the Pacific.

Relations between the U.S. and Chiang Kai-shek's Nationalist government during World War II were sometimes difficult. One big problem was that the Nationalist government insisted on an exchange rate that made their money seem worth much more than it was. Chiang also kept asking for financial help, which led American officials to joke about his name being "Cash-My-Check." Even though the U.S. was stronger, Chiang was sensitive about China being seen as a weaker power. He would be very firm if he felt the U.S. was not treating China with enough respect.

Plans to Bomb Japan

In 1940, before Pearl Harbor, Washington planned a surprise attack on Japanese bases. American pilots and planes, wearing Chinese uniforms, would bomb Japan. These were the Flying Tigers. The U.S. Army was against this plan. They doubted that the Chinese army could build and protect airfields close enough to Japan.

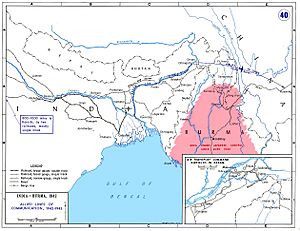

Despite the Army's advice, American civilian leaders liked the idea of China attacking Japan by air. Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau Jr. and President Franklin D. Roosevelt strongly approved. However, the attack never happened. The Chinese had not built or secured any runways close enough to Japan, just as the Army had warned. The American bombers and crews arrived shortly after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. The bombers were then used for the war in Burma against Japan, as they could not reach Japan from secure bases in China.

U.S. Declares War

The United States officially declared war on Japan in December 1941. The Roosevelt government sent huge amounts of aid to Chiang's government, which was then in Chongqing. Soong Mei-ling (Madame Chiang Kai-shek), Chiang's American-educated wife, spoke to the U.S. Congress. She also traveled the country to gather support for China.

Congress changed the Chinese Exclusion Act. Roosevelt also worked to end the unequal treaties by signing the Sino-American New Equal Treaty. However, people began to feel that Chiang's government could not effectively fight the Japanese. Some thought he cared more about defeating the Communists.

Some American officials, like Joseph Stilwell, who spoke fluent Chinese, believed the U.S. should talk to the Communists. This would help prepare for a land invasion of Japan. The Dixie Mission, which started in 1943, was the first official American contact with the Communists. Other Americans, like Claire Lee Chennault, supported using air power and backed Chiang's position.

In November 1943, Roosevelt hosted a meeting with representatives from 44 countries. They discussed rebuilding Allied countries damaged by the war. This effort became the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration. The United States provided most of the money, and China received the most funds. Mistrust grew between the Nationalist government and the U.S. Chiang wanted to control how the money was used in China. He wanted to make sure relief funds did not go to Communist-controlled areas.

In 1944, Chennault successfully demanded that Stilwell be removed. General Albert Coady Wedemeyer replaced Stilwell, and Patrick J. Hurley became the ambassador.

Civil War in Mainland China

After World War II ended in 1945, the fighting between the Nationalists and the Communists exploded into the Chinese Civil War. During World War II, American officials became suspicious about how grants and loans were being spent. Chiang saw efforts to limit funds as an insult to his and China's dignity. This problem got worse during the Civil War.

In November 1946, China and the United States signed a new trade treaty. Chinese newspapers, especially liberal and leftist ones, were doubtful about the treaty. China's legislature worried that the treaty would let American companies control Chinese markets. American businesses were also unhappy, feeling the treaty violated the Open Door Policy.

President Truman sent General George Marshall to China to try and stop the Civil War. However, the Marshall Mission was not successful. In 1948, Marshall, who was then Secretary of State, told Congress in secret that he knew the Nationalists could never defeat the Communists. He said a peace agreement was needed, or the U.S. would have to fight the war itself.

He warned that a large U.S. effort to help the Chinese government fight the Communists would likely become a direct U.S. responsibility. This would involve many forces and resources for a long time. Such a use of U.S. resources would help the Russians or cause a reaction that could lead to another war. He felt the cost of a full effort to stop the Communists would be too high for the results gained.

When it became clear that the KMT would lose control of mainland China in 1949, Secretary of State Dean Acheson published the China White Paper. This paper explained American policy and defended against critics who asked, "Who Lost China?" He announced that the United States would "wait for the dust to settle" before recognizing the new government.

Chinese military forces under Chiang Kai-shek had gone to the island of Taiwan to accept the surrender of Japanese troops. They then withdrew to the island from 1948 to 1949. Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Mao Zedong established the People's Republic of China on mainland China. Taiwan and other islands are still under the control of the Republic of China.

The People's Republic of China and the U.S.

On October 1, 1949, the People's Republic of China was founded. However, the United States continued to recognize the Republic of China (on Taiwan) as the true representative of China. This changed in 1979. The United States signed the Joint Communiqué on the Establishment of Diplomatic Relations. This recognized the People's Republic of China as the only legal government of China. However, the U.S. continued to have relations with the Republic of China by signing the Taiwan Relations Act.

See also

- Republic of China–United States relations for relations since 1948

- Stilwell and the American Experience in China, 1911–45, book by Barbara W. Tuchman

- East Asia–United States relations

- Foreign relations of the Republic of China

- Economic history of China (1912–1949)

- History of China