History of Le Havre facts for kids

Le Havre was founded on October 8, 1517, as a new port by order of King François I. It was built to replace the older harbors of Harfleur and Honfleur, which were becoming too shallow due to silt. The city was first called Franciscopolis after the king. Later, it was renamed Le Havre-de-Grâce ("Harbour of Grace") after a local chapel called Notre-Dame-de-Grâce. The American city of Havre de Grace, Maryland, got its name from this French city.

Contents

Early History of Le Havre

People have lived in the area of Le Havre since Prehistory, about 400,000 years ago.

Many ancient tools and remains from the Neolithic period (New Stone Age) have been found in the lower city and the Montgeon Forest. During this time, the population grew and people started living in small villages. Later, during the Iron Age, Celtic people from the Caletes tribe settled in the region.

In ancient times, river travel on the Seine River helped connect the Gallo-Roman cities near the river's mouth. A Roman road also linked Lillebonne (Juliobona) to the area where Le Havre is today.

The first mention of Graville Abbey was in the 9th century. The village of Leure and its trading port appeared in the 11th century. This port was a safe place for ships waiting for the right tide to enter the port of Harfleur further upstream. Around this time, William Malet, a friend of William the Conqueror, built a castle at Graville and a small fort in Aplemont.

Several small villages of fishermen and farmers, which became the first parishes, grew during the High Middle Ages. During the Hundred Years War, the fortified ports of Leure and Harfleur were destroyed. By the early 1500s, trade was growing, Harfleur's port was silting up, and there was a fear of an English attack. These reasons led King François I to decide to build the port and town of Le Havre.

Founding the Port City

On October 8, 1517, King François I signed the official document to start building the port. Vice Admiral Guyon le Roy was in charge of the first plans. A "big tower" was built to protect the entrance. Even with problems like marshland and storms, the port of Le Havre welcomed its first ship in October 1518.

The king himself visited in 1520. He gave Le Havre special rights forever and gave the city his own symbol, a salamander. The city also became an important meeting point for the French navy during wars. Ships from Le Havre also sailed to Newfoundland to fish for cod.

In 1525, a storm killed about a hundred people and destroyed 28 fishing boats and the Chapel of Notre Dame. In 1536, the chapel was rebuilt with wood and stone. A tall, pointed tower was added in 1540. That same year, Francis I asked Italian architect Girolamo Bellarmato to plan and fortify the city. Bellarmato had full power and designed the Saint-François area with straight streets and rules for house heights. The first school and a grain storage building were built.

By the 1550s, several city organizations were created: the town hall, the Amirauté (a court of justice), a hospital, and local government offices.

The New World attracted many adventurers. Some left from Le Havre, like Villegagnon, who started a colony in Brazil in 1555. By the end of the 1500s, trade grew quickly. Le Havre began receiving products from America like leather, sugar, and tobacco. A famous explorer and mapmaker named Guillaume Le Testu (1509–1573) was a key player in this trade. A dock in Le Havre is still named after him.

On April 20, 1564, Le Havre was the starting point for a French trip to the New World led by René Goulaine de Laudonnière. He created the first French colony at Fort Caroline near where Jacksonville, Florida, is today. The famous artist Jacques le Moyne de Morgues joined this trip. He created the first known drawings by a European of Native Americans in the New World, specifically the Timucua tribes in Florida and Georgia.

Religious Conflicts

The Protestant Reformation gained some followers in Normandy. From 1557, John Venable, a book seller from Dieppe, spread the writings of Martin Luther and John Calvin in the region. The first Protestant church in Le Havre was built in 1600. It was destroyed in 1685 when King Louis XIV removed the rights of Protestants. Le Havre did not have another Protestant place of worship until 1787.

Le Havre was affected by the Wars of Religion. On May 8, 1562, Protestants took over the city, robbed churches, and forced Catholics out. Fearing an attack by the king's army, they asked the English for help, and English troops arrived. The English built defenses under a treaty.

However, King Charles IX's troops, led by Anne de Montmorency, attacked Le Havre. The English were finally forced out on July 29, 1563. The fort built by the English was destroyed, and the tower of the Cathedral of Notre-Dame was made shorter by the king's order. He then ordered a new citadel to be built, which was finished in 1574. New defenses were added between 1594 and 1610. In 1581, work began on a canal between Harfleur and the Seine River.

The 17th and 18th Centuries

Le Havre's role as a defense point was strengthened. The port began to be modernized in the 16th century under orders from Cardinal Richelieu, who was the city's governor. The arsenal (a place for making and storing weapons) and the Roy Basin were developed. The city walls were made stronger, and a fortress was built. It was in this fortress that Cardinal Mazarin imprisoned important princes.

At the start of King Louis XIV's rule, Colbert decided to improve the port and military structures. This work lasted 14 years. In 1669, Colbert opened the canal from Le Havre to Harfleur, also called the "canal Vauban."

Le Havre became more important for sea trade in the 17th century. The Company of the Orient set up operations there in 1643. Exotic products like sugar, cotton, tobacco, coffee, and spices were imported from America. The slave trade made local traders rich, especially in the 18th century. Le Havre was the third largest French port involved in the slave trade, after Nantes and La Rochelle, with 399 slave trade trips in the 17th and 18th centuries. However, sea trade was affected by international relations and European wars. The wars of Louis XIV and Louis XV temporarily stopped Le Havre's growth. The English and Dutch attacked the city several times, in 1694 and 1696.

In 1707, Michel Dubocage, a captain from Le Havre, explored the Pacific Ocean and reached Clipperton Island. When he returned, he became rich by starting a trading business. He bought a large house in the Saint-François area, which is now a museum. Another captain from Le Havre, Jean-Baptiste d'Après de Mannevillette (1707–1780), worked for the East India Company and mapped the coasts of India and China.

From the mid-18th century, wealthy traders built homes along the coast. In 1749, Madame de Pompadour wanted to see the sea, and Louis XV chose Le Havre for her visit. This visit was very expensive for the city.

In 1759, the city was a gathering point for a planned French invasion of Britain. Thousands of troops, horses, and ships were brought together there. However, many of the boats were destroyed in an attack on Le Havre, and the invasion was stopped after a naval defeat.

Le Havre's economic growth led to its population increasing to 18,000 people by 1787. It also led to changes in the port and city. A Tobacco Factory was built, shipyards expanded, a new arsenal was added, and a place for trading goods was created. During a visit in 1786, Louis XVI approved a plan to make the city four times bigger. François Laurent Lamandé was chosen to lead this project.

The French Revolution Era (1789–1815)

Between 1789 and 1793, the port of Le Havre was the second largest in France. The Triangular trade (which included the slave trade) continued until the war and its end. The port remained important because of the grain trade (supplying Paris) and its closeness to the British enemy.

The events of the French Revolution also affected Le Havre. Delegates were chosen in March 1789 to write down complaints. Public protests happened in July, and the National Guard was formed. A mayor was elected in 1790. The year 1793 was difficult for France and Le Havre due to war, local uprisings, and a slow economy. The religious Terror turned Notre Dame Cathedral into a "Temple of Reason." The city became a sub-prefecture in 1799–1800.

Under the Empire, Napoleon I visited Le Havre and ordered new forts to be built. A Chamber of Commerce was started in 1800. However, because of the war against Britain and a trade blockade, port activity decreased, and pirate activity increased. Le Havre's population dropped to 16,231 people by 1815.

Growth in the 19th Century

After the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars ended, trade returned to normal as the British threat lessened. This new peace and economic growth led to many people moving to Le Havre. The city quickly grew beyond its old walls, and new neighborhoods appeared. Many poor people still lived in crowded conditions in the Saint Francis area. Diseases like cholera and typhoid fever caused hundreds of deaths in the 1830s to 1850s.

Throughout the 19th century, the city became more diverse. When sea trade was good, workers from the Pays de Caux moved to Le Havre because of problems in the weaving industry. A large community of Bretons (10% of the population by the late 1800s) changed the city's culture. Italians, Poles, and North Africans also worked on the docks and in factories. The city's economic success attracted business owners from Anglo-Saxon, Nordic, and Alsatian regions.

The city and its port were changed by major development projects throughout the 19th century. These projects were sometimes stopped by political and economic problems. A new stock exchange and a commercial basin were built in the first half of the century. Gas lighting was installed in 1835, trash collection started in 1844, and sewerage systems were built, showing a focus on modernizing the city. By the mid-century, the old city walls were torn down, and nearby communities were added to the city, causing the population to grow sharply.

The period from 1850 to 1914 was a great time for Le Havre. Except for a few years of economic slowdown (during the American Civil War and the Franco-Prussian War), trade boomed. The city became more beautiful with elegant new buildings like wide boulevards, a city hall, a courthouse, and a new stock exchange.

The effects of the industrial revolution became more visible in Le Havre. The first steam dredge (a machine to clear waterways) was used in 1831. Shipyards grew with Augustin Normand. Frederic Sauvage developed his first propeller in Le Havre in 1833. The railway arrived in 1848, connecting Le Havre to other places. Docks and warehouses were also built around this time. However, the industrial sector was still small in the 19th century. Factories were mostly related to port traffic, like shipyards, sugar refineries, and rope factories. The banking sector grew but still relied on outside support. The city had few professionals and government workers. There were also not enough schools, even in the 1870s.

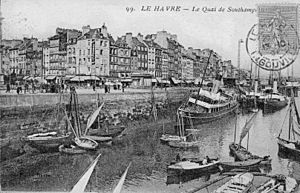

Before the First World War, Le Havre was Europe's main port for coffee. It imported about 250,000 tons of cotton and 100,000 tons of oil. European coastal shipping brought wood, coal, wheat from Northern Europe, and wine and oil from the Mediterranean. The end of the slave trade slowly changed the types of goods traded. Le Havre became not only a place for American goods to enter but also a transit point for people moving to the USA. Transatlantic steamer travel grew in the 1830s.

Under the July Monarchy, Le Havre became a popular Seaside resort for people from Paris. Marine baths were created around this time. In 1889, the maritime boulevard was built, with the Villa Maritime overlooking it. The casino Marie-Christine (1910) and the Palace of Regattas (1906) attracted wealthy people, and the first Beach huts were set up on the beach. However, the late 19th century and the Belle Époque also brought social problems due to rising prices and unemployment. From 1886, worker protests shook the city, and Socialists became more influential.

Wartime (1914–1945)

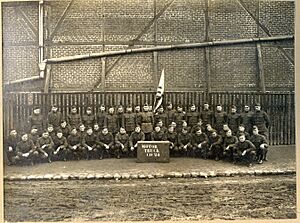

The First World War caused many deaths in Le Havre. About 6,000 people from the city died, mostly soldiers. The city itself was not heavily destroyed because the war front was far to the north. However, several ships were sunk by German submarines near the harbor. A notable event was the Belgian government moving to Sainte-Adresse, just outside Le Havre, after being forced to flee German occupation. The city served as a base for the Triple Entente (Allied powers), especially for British warships. About 1.9 million British soldiers passed through the port of Le Havre.

The period between the two World Wars saw a stop in population growth, social unrest, and economic problems. After the conflict, rising prices ruined many people on pensions. Le Havre became mostly a working-class city. Shortages and high prices led to a big strike in 1922, which caused a state of emergency to be declared. In 1936, the Breguet factory in Le Havre was occupied by striking workers. This marked the beginning of the labor movement under the Popular Front government.

Economically, the strong growth of the late 19th century seemed to be over. Ports in northern Europe competed strongly with Le Havre, and major port development slowed down. However, oil imports continued to grow, and refineries appeared east of Le Havre. The global economic crisis of 1929 and trade protection policies hindered trade growth. Only the travel industry did relatively well, with 500,000 passengers in 1930. The famous liner Normandie began sailing to New York in 1935.

In the Second World War, German forces occupied Le Havre from spring 1940, causing many people to leave. The Germans made it a naval base to prepare for an invasion of the United Kingdom. They also built the Festung Le Havre, a fortified area with bunkers, pillboxes, and artillery batteries, as part of the Atlantic Wall. For the people of Le Havre, daily life was hard due to shortages, censorship, and bombings.

Many people chose to leave the city at dusk by foot, bike, or wagon, returning during the day after the Allied air bombings were over.

Le Havre was bombed 132 times by the Allies during the war. The Nazis also destroyed port structures and sank ships before leaving the city. However, the worst destruction happened on September 5 and 6, 1944, when the British Royal Air Force bombed the city center and port to weaken the German occupiers. This event is often called the "storm of iron and fire."

The results of the bombing were terrible: 5,000 deaths (including 1,770 in 1944), 75,000 to 80,000 injured, 150 hectares (about 370 acres) of land flattened, and 12,500 buildings destroyed. The port was also ruined, with about 350 shipwrecks at the bottom of the sea. Le Havre was freed by Allied troops on September 12, 1944.

Despite the huge damage, Le Havre became the site of some of the biggest supply depots for American troops in World War II. Thousands of American soldiers arrived at "Cigarette Camps" (like Philip Morris, Herbert Tareyton, Wings, and Pall Mall Camps) near the town before being sent to fight. The port also became key for the U.S. Army's supply operations.

Le Havre After 1945

General Charles de Gaulle visited Le Havre on October 7, 1944. The city received the Legion of Honour award on July 18, 1949, for its "heroism in facing its destruction."

In spring 1945, Raoul Dautry, from the Ministry of Reconstruction, gave the project to rebuild Le Havre to Auguste Perret. The city council asked Brunau to join the planning team, but he left soon after due to disagreements with Perret. Perret wanted to clear away the old structures and use modern ideas of structural classicism. The main building material was concrete, and the general plan was a grid of straight lines. Officially, the reconstruction was finished in the mid-1960s.

The main streets, Boulevard François I, Avenue Foch, and Rue de Paris, guided travelers north, south, east, and west of the city center. The shopping area of Rue de Paris, which existed before the war, was redesigned with wide sidewalks. A surrounding grid of streets allowed for open shopping areas, unlike the crowded old parts of the city.

The Place de l’Hotel de Ville, the central square, was lined with 330 apartments of different sizes, designed to hold 1,000 people. Government funds also allowed for the building of tall apartment blocks in residential areas. These new apartments had modern features like central heating. Avenue Foch was 80 meters (about 260 feet) wide, a bit wider than the Champs-Élysées in Paris. The best apartments were built here, facing the northern sunlight.

Beyond the concrete buildings of the inner city, the Saint-François neighborhood was rebuilt with red-brick homes and slate roofs. Aplemont's three-square-kilometer (about 1.16 square miles) rebuild included detached houses, two-story row houses, and small apartment buildings. A church, community center, and shops were also part of the new design. The city also added 7.7 square kilometers (about 3 square miles) of green spaces, including parks, gardens, and woodlands. This meant an average of 41 square meters (about 441 square feet) of green space per person, which was a lot for a European city at that time.

The Museum of Modern Art and the first House of Culture in the region were opened in 1961 by André Malraux. The city grew by adding the areas of Bleville, Sanvic, and Rouelles.

In the 1970s, economic problems due to industries closing down changed the port's trade. For example, the Ateliers et chantiers du Havre (ACH) shipyard closed in 1999. 1974 also saw the end of the ocean liner service to New York by the France. The Energy crisis caused an industry slump. Since then, the city has focused on restructuring its economy, mainly towards the tertiary sector (services). This included opening the University of Le Havre in the 1980s, developing tourism, and modernizing the port with the Port 2000 project.

UNESCO declared the city center of Le Havre a World Heritage Site on July 15, 2005. This recognized its "innovative use of concrete's potential." The 133-hectare (about 328-acre) area was seen by UNESCO as "an exceptional example of architecture and town planning of the post-war era," making it one of the few modern World Heritage Sites in Europe.

Images for kids

See also

- Timeline of Le Havre

| Mary Eliza Mahoney |

| Susie King Taylor |

| Ida Gray |

| Eliza Ann Grier |