History of Tuvalu facts for kids

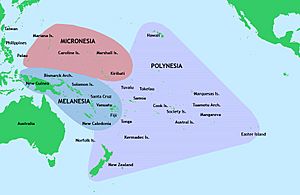

The first people to live in Tuvalu were Polynesians. Their ancestors came from Southeast Asia, specifically from Taiwan, and traveled through Melanesia and across the Pacific islands of Polynesia.

European ships started visiting the islands and giving them new names. In 1819, the island of Funafuti was named Ellice's Island. Soon, the name Ellice was used for all nine islands, honoring English mapmaker Alexander George Findlay.

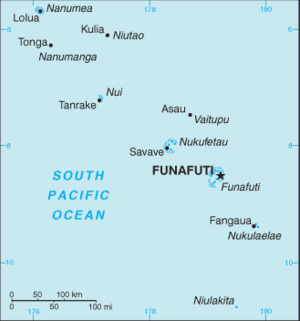

The United States claimed Funafuti, Nukufetau, Nukulaelae, and Niulakita in 1856 under the Guano Islands Act. This claim was later given up in a friendship treaty between Tuvalu and the United States in 1983.

Great Britain took control of the Ellice Islands in the late 1800s. Captain Herbert William Sumner Gibson officially declared each island a British Protectorate between October 9 and 16, 1892. The islands were managed by Britain from 1892 to 1916 as part of the British Western Pacific Territories. Then, they became part of the Gilbert and Ellice Islands Colony until 1976.

In 1974, the people of the Ellice Islands voted to become a separate British territory called Tuvalu. This led to the Gilbert Islands becoming Kiribati when they gained independence. Tuvalu officially became a separate colony on October 1, 1975. Tuvalu then gained full independence within the Commonwealth on October 1, 1978. On September 5, 2000, Tuvalu became the 189th member of the United Nations.

The Tuvalu National Library and Archives keeps important documents about Tuvalu's culture, society, and politics. This includes old records from the time it was a colony and current government archives.

Contents

- Tuvalu's Early History

- European Explorers in the Pacific

- Trading and Traders

- Scientific Expeditions and Visitors

- Traditional Beliefs

- Arrival of Christianity

- British Rule

- World War II and Operation Galvanic

- Becoming Self-Governing

- Island Government: Falekaupule and Kaupule

- Broadcasting and News

- Health Services

- Education in Tuvalu

- Heritage and Culture

- Land Ownership

- Tsunamis and Cyclones

- Tuvalu and Climate Change

- See also

Tuvalu's Early History

Tuvaluans are a Polynesian people. Their history goes back about 3,000 years, when people started migrating across the Pacific. Scientists believe Pacific Islanders have a mixed background from Asia and Melanesia. Fiji played a key role in how Polynesians spread from west to east.

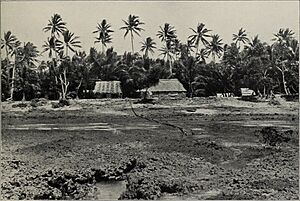

Before Europeans arrived, people often traveled between the islands by canoe. Polynesians were skilled navigators, using double-hulled sailing canoes or outrigger canoes for long journeys. Eight of Tuvalu's nine islands were inhabited. This is why the name Tuvalu means "eight standing together" in the Tuvaluan language.

Some evidence of fire in the Caves of Nanumanga suggests people might have lived there thousands of years ago. It's thought that Polynesians spread from the Samoan Islands to the Tuvaluan atolls. Tuvalu then became a stepping stone for migration to other Polynesian communities in Melanesia and Micronesia.

An important creation story in Tuvalu is about te Pusi mo te Ali (the Eel and the Flounder). They are said to have created the islands. Te Ali (the flounder) is believed to be the origin of Tuvalu's flat atolls. Te Pusi (the eel) is the model for the coconut palms, which are very important to Tuvaluans.

Stories about the ancestors of Tuvaluans differ from island to island. On Niutao, people believe their ancestors came from Samoa in the 12th or 13th century. On Funafuti and Vaitupu, the first ancestor is also said to be from Samoa. But on Nanumea, the founding ancestor is described as being from Tonga.

These stories connect to the Tu'i Manu'a Confederacy, based in Samoa. This group, led by the Tu'i Manú'a chiefs, likely controlled much of Western Polynesia around the 10th and 11th centuries.

Tuvalu was also visited by Tongans in the mid-13th century and was influenced by Tonga. Captain James Cook saw the Tuʻi Tonga kings during his visits to Tonga. The influence of the Tuʻi Tonga line of Tongan kings, which started in the 10th century, was very strong in Polynesia and parts of Micronesia.

The oral history of Niutao says that in the 15th century, Tongan warriors were defeated in a battle on the reef of Niutao. Tongan warriors invaded Niutao again later in the 15th century and were pushed back. They tried a third and fourth invasion in the late 16th century, but were defeated again.

Tuvalu is on the western edge of the Polynesian Triangle. This means the northern islands of Tuvalu, especially Nui, have connections to Micronesians from Kiribati. Niutao's oral history also mentions that in the 17th century, warriors from Kiribati invaded twice and were defeated in battles on the reef.

European Explorers in the Pacific

Europeans first saw Tuvalu on January 16, 1568. This was during the journey of Álvaro de Mendaña de Neira, a Spanish explorer. He sailed past the island of Nui and named it Isla de Jesús ("Island of Jesus"). Mendaña met the islanders but could not land. On his second trip, he passed Niulakita on August 29, 1595, naming it La Solitaria.

Captain John Byron sailed through the islands of Tuvalu in 1764. He was circling the globe as captain of the Dolphin (1751). Byron mapped the atolls as Lagoon Islands.

The first recorded sighting of Nanumea by Europeans was by Spanish naval officer Francisco Antonio Mourelle de la Rúa. He sailed past it on May 5, 1781, as captain of the frigate La Princesa. He named Nanumea San Augustin. Experts believe he also sailed past Niutao that same day, solving "The Mystery of Gran Cocal." Mourelle's map called it El Gran Cocal ('The Great Coconut Plantation'). The people of Niutao came out in canoes, bringing coconuts.

In 1809, Captain Patterson on the ship Elizabeth saw Nanumea while trading from Sydney, Australia, to China.

In May 1819, Arent Schuyler de Peyster, captain of the ship Rebecca, saw Funafuti. He named it Ellice's Island after Edward Ellice, an English politician. The next morning, de Peyster saw another group of islands, which he named "De Peyster's Islands." This atoll is now known as Nukufetau.

In 1820, Russian explorer Mikhail Lazarev visited Nukufetau. In May 1824, Louis Isidore Duperrey, captain of La Coquille, sailed past Nanumanga. A Dutch expedition found Nui on June 14, 1825, and named its main island Nederlandsch Eiland.

Whalers started coming to the Pacific, but they rarely visited Tuvalu because landing on the atolls was difficult. Captain George Barrett was the first whaler known to hunt near Tuvalu in November 1821. He traded coconuts with the people of Nukulaelae and also visited Niulakita. A camp was set up on Sakalua islet of Nukufetau to melt whale blubber.

Between 1862 and 1863, Peruvian ships engaged in "blackbirding" (forced labor trade). They took people from smaller Polynesian islands, including Tuvalu, to work in Peru. On Funafuti and Nukulaelae, local traders helped the "blackbirders" find islanders. Reverend Archibald Wright Murray reported that about 180 people were taken from Funafuti and 200 from Nukulaelae in 1863.

Trading and Traders

John O'Brien was the first European to live in Tuvalu, becoming a trader on Funafuti in the 1850s. He married Salai, the daughter of Funafuti's chief. Trading companies from Sydney and Germany began the coconut-oil trade in Tuvalu. The German company J.C. Godeffroy und Sohn dominated the copra (dried coconut meat) trade by the 1870s.

These trading companies hired European traders, called palagi, to live on the islands. Some islands had competing traders, while drier islands only had one. Louis Becke, who later became a writer, was a trader on Nanumanga and then Nukufetau. George Westbrook and Alfred Restieaux had stores on Funafuti that were destroyed by a cyclone in 1883.

A German trading firm, H. M. Ruge and Company, caused problems when it threatened to take over Vaitupu island if a large debt was not paid back. The people of Vaitupu still celebrate Te Aso Fiafia (Happy Day) on November 25 each year. This day remembers November 25, 1887, when the last payment of the debt was made.

By the late 1880s, steamships started replacing sailing ships. The number of trading companies in Tuvalu decreased. In 1892, Captain Edward H. M. Davis of HMS Royalist reported on the traders on each island. The 1880s had the most European traders living on the atolls.

After 1900, new companies like Burns Philp and Levers Pacific Plantations started trading in the Ellice Islands. However, the number of European traders living in Tuvalu continued to decline. By 1909, there were no resident European traders representing the big firms. Tuvaluans then took over running the trading stores on each island.

In 1926, Donald Gilbert Kennedy, a headmaster on Vaitupu, helped set up the first co-operative store. This became a model for other co-op stores in the Gilbert and Ellice Islands Colony, replacing the stores run by European traders.

Scientific Expeditions and Visitors

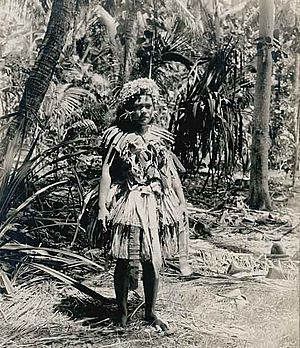

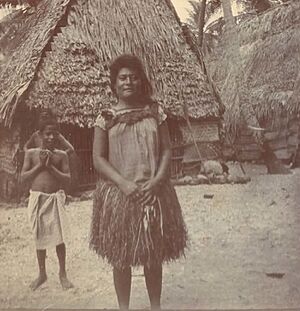

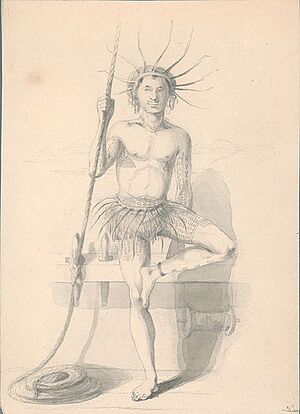

The United States Exploring Expedition, led by Charles Wilkes, visited Funafuti, Nukufetau, and Vaitupu in 1841. During this visit, Alfred Thomas Agate recorded the clothing and tattoo patterns of men from Nukufetau.

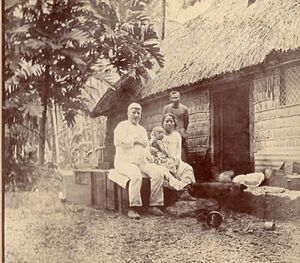

In 1890, writer Robert Louis Stevenson, his wife Fanny Vandegrift Stevenson, and her son Lloyd Osbourne sailed through the central Pacific. They visited three of the Ellice Islands. Fanny wrote about their journey in The Cruise of the Janet Nichol, which included photos taken by Robert Louis Stevenson and Lloyd Osbourne.

In 1894, Count Rudolf Festetics de Tolna and his family visited Funafuti. The Count took photos of people on the island.

The `Darwin's Drill` site on Funafuti is where the Royal Society of London drilled into the coral reef. They wanted to study how coral reefs form and if shallow water organisms could be found deep within the coral. This research followed Charles Darwin's work on coral reefs. Drilling happened in 1896, 1897, and 1911. The results supported Darwin's theory that atolls form as islands slowly sink.

Harry Clifford Fassett, a photographer, recorded people and scenes at Funafuti in 1900 during a visit by the USFC Albatross.

Traditional Beliefs

Before Christianity arrived, the objects of worship varied from island to island. However, ancestor worship was common, as noted by Reverend Samuel James Whitmee in 1870.

In 1896, Professor William Johnson Sollas recorded an oral history of Funafuti from Erivara, the chief of Funafuti. Erivara described the spiritual beliefs before Christianity. People first worshipped nature, like thunder and lightning, and also birds and fish. Later, they worshipped spirits. Eventually, the belief system focused on priests or spirit-masters (vaka-atua), who connected people to spirits and special objects like a red stone called Teo. Daily activities like fishing were linked to ceremonies involving these objects and spirits. The vaka-atua were also healers.

Arrival of Christianity

Some traders, like Tom Rose and Robert Waters, actively spread Christianity. Rose held Sunday services. However, some traders also wanted to destroy old religions so islanders would focus more on trade.

The first Christian missionary arrived in Tuvalu in 1861. Elekana, a deacon from the Cook Islands, drifted for 8 weeks in a storm before landing at Nukulaelae. He began teaching Christianity there. He was trained at Malua Theological College in Samoa, a school run by the London Missionary Society.

In 1865, Reverend Archibald Wright Murray of the London Missionary Society arrived as the first European missionary. By 1878, Protestantism was well established, with preachers on each island. In the late 1800s, the ministers of what became the Church of Tuvalu were mostly Samoans. They influenced the development of the Tuvaluan language and music.

British Rule

In 1876, Britain and Germany agreed to divide the western and central Pacific into "spheres of influence." In 1877, the Governor of Fiji also became the High Commissioner for the Western Pacific.

German ships visited Funafuti and Vaitupu in 1878 and 1883. They made trade agreements with the islanders.

Ships of the Royal Navy also visited the islands in the 1800s. Captain Edward H. M. Davis of HMS Royalist visited all the Ellice Islands in 1892. He reported that the islanders wanted him to raise the British flag. Captain Herbert Gibson of HMS Curacoa was sent to the islands and formally declared them a British protectorate between October 9 and 16, 1892.

From 1892 to 1916, the Ellice Islands were governed as a British protectorate. The first Resident Commissioner, Charles Richard Swayne, wrote down the laws of each island. These became the Native Laws of the Ellice Islands in 1894. These laws set up an administrative structure for each island and included criminal laws. They also made school attendance compulsory for children. On each island, the High Chief (Tupu) was in charge of keeping order, helped by a magistrate and police. The High Chief was also assisted by councillors (Falekaupule). The Falekaupule is the traditional assembly of elders on each island.

In 1916, the Gilbert and Ellice Islands Colony was formed, lasting until 1974. New laws in 1917 changed the role of the High Chief and limited the number of members in the Kaupule (the executive part of the Falekaupule). The magistrate became the most important official.

In 1930, Resident Commissioner Arthur Grimble issued new strict laws. Islanders tried to get these laws changed, but they were ignored until a government officer sent a copy to a member of the English Parliament.

Donald Gilbert Kennedy arrived in 1923 and became headmaster of a new government school on Funafuti. He moved the school to Vaitupu in 1924 because there was more food there. He later became the District Officer on Funafuti from 1932 to 1939.

World War II and Operation Galvanic

During World War II, the Ellice Islands, as a British colony, sided with the Allies. The Japanese had invaded islands in what is now Kiribati.

The United States Marine Corps landed on Funafuti on October 2, 1942, and on Nanumea and Nukufetau in August 1943. The Ellice Islands were used as a base to prepare for attacks on the Gilbert Islands, which were held by Japanese forces.

Coastwatchers were placed on some islands to spot Japanese activity. Islanders helped American forces build airfields on Funafuti, Nanumea, and Nukufetau. On Funafuti, islanders moved to smaller islets so Americans could build the airfield, a hospital, and a naval base.

Building the airfields meant losing coconut trees and gardens. However, islanders received food and goods from the American forces. Many coconut, breadfruit, and pandanus trees were destroyed. Building the runway on Funafuti also meant losing land used for growing pulaka and taro.

A detachment of the 2nd Naval Construction Battalion (the Seabees) built a seaplane ramp on Funafuti. A compacted coral runway was also built on Fongafale. On December 15, 1942, float planes arrived at Funafuti for anti-submarine patrols. PBY Catalina flying boats were also stationed there.

In April 1943, a detachment built a gasoline tank farm. In August 1943, the 16th Battalion arrived to build Nanumea Airfield and Nukufetau Airfield. These atolls were like "unsinkable aircraft carriers" for the Battle of Tarawa and the Battle of Makin, which started on November 20, 1943.

USS LST-203 was grounded on the reef at Nanumea on October 2, 1943, to unload equipment. Its rusting hull is still there. The Seabees also blasted an opening in the reef at Nanumea, now called the 'American Passage'.

The 5th and 7th Defense Battalions were stationed in the Ellice Islands to defend naval bases.

The first attack from Funafuti airfield happened on April 20, 1943. Bombers from the 371 and 372 Bombardment Squadrons attacked Nauru. The next day, the Japanese raided Funafuti, destroying one bomber. On April 22, 12 bombers attacked Tarawa. Funafuti airfield became the headquarters for the United States Army Air Forces VII Bomber Command in November 1943.

Funafuti was attacked by air several times in 1943. On April 23, 1943, a bomb hit a church shortly after people were persuaded to move to dugouts. Two American soldiers and an elderly Tuvaluan man were killed. Japanese planes continued to raid Funafuti in November 1943.

USN Patrol Torpedo Boats (PTs) were based at Funafuti from November 1942 to May 1944. They operated against Japanese ships and were involved in patrol and rescue duties. A float plane rescued Captain Eddie Rickenbacker near Nukufetau.

By mid-1944, as the war moved north, American forces left Tuvalu. After the war, the military airfield on Funafuti became Funafuti International Airport.

Becoming Self-Governing

After World War II, the United Nations Organisation started a process of decolonization. British colonies in the Pacific began moving towards self-determination. The focus was first on developing the administration of the Gilbert and Ellice Islands. In 1947, Tarawa in the Gilbert Islands became the administrative capital.

Conferences were held every two years from 1956 to 1962, with officials and representatives from each island. In 1963, an Advisory Council was created. In 1964, an Executive Council was established. The Resident Commissioner now had to consult this council when making laws and decisions for the colony.

Local government on each island continued until 1965, when Island Councils were formed. Islanders elected councillors who then chose the council's President.

A constitution in 1967 created a House of Representatives for the Gilbert and Ellice Islands Colony. It had 7 appointed officials and 23 elected members. Tuvalu elected 4 members. However, Tuvaluans were concerned about being a minority and wanted equal representation with the I-Kiribati (people from the Gilbert Islands). A new constitution in 1971 gave each Tuvaluan island (except Niulakita) one representative. But this did not stop the movement for Tuvaluan independence.

In 1974, a general election was held, and a referendum asked if the Gilbert Islands and Ellice Islands should have separate governments. The result was that 3,799 Elliceans voted for separation, and 293 voted to stay together.

As a result, separation happened in two steps. On October 1, 1975, Tuvalu became a separate British territory with its own government. On January 1, 1976, separate administrations were created from the civil service.

Elections for the House of Assembly of the British Colony of Tuvalu were held on August 27, 1977. Toaripi Lauti became Chief Minister on October 1, 1977.

Toaripi Lauti became the first Prime Minister of the Parliament of Tuvalu on October 1, 1978, when Tuvalu became an independent nation. The parliament meets at the Vaiaku maneapa.

Island Government: Falekaupule and Kaupule

The Falekaupule on each of the Islands of Tuvalu is the traditional assembly of elders. Its name means "grey-hairs of the land" in the Tuvaluan language. The Falekaupule Act (1997) says the Falekaupule is the "traditional assembly in each island ... composed in accordance with the Aganu of each island." Aganu means traditional customs and culture.

Today, the powers of the Falekaupule are shared with the Kaupule on each island. The Kaupule is the executive part of the Falekaupule, and its members are elected. The Kaupule has an elected president and an appointed treasurer.

The maneapa on each island is traditionally an open meeting place where chiefs and elders discuss important matters. Today, a maneapa is a building for community meetings or celebrations. The maneapa system refers to the rule of traditional chiefs and elders.

Broadcasting and News

After independence, the only newspaper publisher and public radio organization in Tuvalu was the Broadcasting and Information Office (BIO). The Tuvalu Media Corporation (TMC) was created in 1999 to take over the BIO's radio and print publications. However, in 2008, it was decided that operating as a corporation was not profitable. So, the Tuvalu Media Corporation became the Tuvalu Media Department (TMD) under the Prime Minister's Office.

Health Services

A hospital was built on Funafuti in 1913. Tuvaluans provided medical services after being trained as doctors or nurses at the Suva Medical School in Fiji. Women's committees also played an important role in health and hygiene from about 1930.

During World War II, the hospital on Fongafale atoll was taken apart because American forces built an airfield there. The hospital moved to Funafala atoll. After the war, the hospital returned to Fongafale.

In 1974, the Gilbert and Ellice Islands Colony was dissolved, and the Colony of Tuvalu was established. Tuvalu became independent in 1978. A new 38-bed central hospital was built at Fakaifou on Fongafale atoll with aid from New Zealand. It opened in 1975 and was named Princess Margaret Hospital. The current hospital building was finished in 2003 with Japanese funding.

Non-government organizations also provide health services, such as the Tuvalu Red Cross Society and the Tuvalu Diabetics Association.

Tuvaluans have always consulted, and still consult, traditional herbal medicine practitioners (Tufuga). They use these treatments alongside or in addition to modern medical care.

Education in Tuvalu

Developing the Education System

The London Missionary Society (LMS) started a mission school on Funafuti. The LMS also opened a primary school at Motufoua on Vaitupu in 1905. This school aimed to prepare young men for the LMS seminary in Samoa. It later became the Motufoua Secondary School. Another school, Elisefou (New Ellice), was on Vaitupu from 1924 to 1953.

From 1953 to 1975, Tuvaluan students could take tests to enter the King George V Secondary School for boys and the Elaine Bernacchi Secondary School for girls. These schools were on Tarawa in the Gilbert Islands.

The Church of Tuvalu took over the LMS's education activities. From 1905 to 1963, Motufoua only accepted students from LMS church schools. In 1963, the LMS and the government started working together. In 1970, a secondary school for girls opened at Motufoua. After Tuvalu separated from the Gilbert Islands in 1974, students from Tarawa transferred to Motufoua. The Church and government jointly managed the school until the Department of Education took full responsibility.

Fetuvalu Secondary School, a day school run by the Church of Tuvalu, is on Funafuti. It reopened in 2003 after being closed for five years.

In 2011, the Fusi Alofa Association Tuvalu (FAA – Tuvalu) opened a school for children with special needs.

Community Training Centres (CTCs) have been set up in primary schools on each atoll. These centers offer vocational training in carpentry, gardening, farming, sewing, and cooking for students who don't go on to secondary school. Adults can also attend courses at CTCs.

Education in the 21st Century

The University of the South Pacific (USP) has an Extension Centre in Funafuti. The government of Tuvalu, with help from the Asian Development Bank, has created plans to improve education.

The Education Department's priorities for 2012–2015 included providing equipment for e-learning at Motufoua Secondary School. They also planned to set up a multimedia unit to create educational content.

In 2010, there were 1,918 students taught by 109 teachers. Nauti School on Funafuti is the largest primary school, with over 900 students.

Four higher education institutions offer technical and vocational courses: Tuvalu Maritime Training Institute (TMTI), Tuvalu Atoll Science Technology Training Institute (TASTII), Australian Pacific Training Coalition (APTC), and the University of the South Pacific (USP) Extension Centre.

Education and National Strategy Plans

Tuvalu's education strategy is part of its national development plans, like Te Kakeega III (National Strategy for Sustainable Development 2016–2020). These plans aim to give people the knowledge and skills they need to be self-reliant. They focus on improving teaching quality, school facilities, and vocational training.

The national strategy plan for 2021–2030 is called “Te Kete.” This name refers to a traditional basket made from coconut leaves. Symbolically, “Te Kete” also has a religious meaning for Tuvaluan Christian traditions, referring to the basket that saved Moses.

Heritage and Culture

Architecture

Traditional Tuvaluan buildings were made from plants and trees found on the islands. These included timber from pouka, ngia, miro, tonga, and fau. Fibers from coconuts, ferra, and fala (pandanus) were also used. Buildings were constructed without nails, instead tied together with plaited rope made from dried coconut fiber.

After Europeans arrived, iron products like nails and corrugated roofing were used. Modern buildings in Tuvalu are made from imported materials like timber and concrete.

Church and community buildings (maneapa) are often painted with a white coating called lase. This is made by burning dead coral with firewood, then mixing the white powder with water.

Art of Tuvalu

Tuvaluan women use cowrie and other shells in traditional handicrafts. Their artistic traditions are seen in clothing designs and decorations on mats and fans. Crochet (kolose) is another art form practiced by Tuvaluan women. Traditional designs are also used in everyday items like canoes and fish hooks made from natural materials.

Traditional Uses of Plants

Plants and trees from the native forests were used for many things:

- Food: Coconut and Ferra (native fig).

- Fiber: Coconut, Ferra, Fala (Screw Pine), and Fau (woman's fiber tree).

- Timber: Fau, Pouka, Ngia, Miro, and Tonga.

- Dye: Valla valla, Tonga, and Nonou.

- Scent: Fetau, Jiali, Boua, Valla valla, and Crinum.

- Medicine: Tulla tulla, Nonou, Tausoun, Valla valla, Talla talla gemoa, Lou, and Lakoumonong.

These plants are still used in the Art of Tuvalu to make traditional artwork and crafts. Tuvaluan women continue to make Te titi tao, a traditional skirt made of dried pandanus leaves dyed with Tongo and Nonu. This art is passed down from older women to younger women.

Traditional Fishing Canoes (paopao)

Tuvaluans build traditional outrigger canoes. A 1996 survey on Nanumea found about 80 canoes. In 2020, there were about 50, with some families still practicing traditional canoe building. However, finding mature fetau trees for building is becoming harder.

A skilled woodworker (tofuga or tufunga) from a family would build a canoe using a suitable tree on their land. Other tufunga would help. The ideal canoe shape was like a whale (tafola) or a bonito (atu). Before steel tools, tufunga used shell and stone adzes, which needed constant sharpening. With steel tools, fewer tufunga were needed. Each morning, the tufunga would perform a religious ceremony over the adzes before starting work.

Donald Gilbert Kennedy described the building of traditional outrigger canoes (paopao) and their variations on Vaitupu and Nanumea. These were reef-type canoes, designed to be carried over the reef and paddled. The traditional outrigger canoes from Nui were built to be sailed over the Nui lagoon. Their outrigger booms were longer, making them more stable for sailing.

Dance and Music

The traditional music of Tuvalu includes several dances, such as fakaseasea, fakanau, and fatele.

Heritage

The aliki were the leaders of traditional Tuvaluan society. They had tao aliki, or assistant chiefs, who helped manage daily activities like fishing and communal work. The sisters and daughters of the aliki made sure women were doing traditional tasks like weaving baskets, mats, and clothing. The elders of the community were the male heads of each family (sologa). Each family had a specific task (pologa) for the community, such as being skilled builders, fishermen, farmers, or warriors. These skills were passed down through families.

An important building is the falekaupule or maneapa, the traditional island meeting hall. Important matters are discussed here, and it's used for weddings and community activities like a fatele (music, singing, and dancing). Falekaupule is also the name for the council of elders, the traditional decision-making body on each island.

Tuvalu does not have any museums yet, but creating a Tuvalu National Cultural Centre and Museum is part of the government's plan.

Land Ownership

Donald Gilbert Kennedy described how Pulaka pits (for growing a root crop) were usually shared among different families. Land ownership evolved from a system called Kaitasi ("eat-as-one"), where land was held by family groups. Over time, it changed to Vaevae ("to divide"), where land was held by individual owners. In the Vaevae system, a pit might have many small individual plots marked by stones or imaginary lines. The elders of each island traditionally decided land inheritance and resolved disputes.

Tsunamis and Cyclones

Tuvalu's low-lying islands are very vulnerable to tsunamis and cyclones. Nui was hit by a giant wave on February 16, 1882, possibly caused by earthquakes or volcanic eruptions in the Pacific. Tuvalu experienced about three tropical cyclones per decade between the 1940s and 1970s, but eight occurred in the 1980s. The impact of cyclones depends on wind strength and whether they happen during high tides.

George Westbrook recorded a cyclone that hit Funafuti in 1883. Another cyclone struck Nukulaelae on March 17–18, 1886. Captain Edward H. M. Davis noted in 1892 that a severe cyclone devastated the Ellice Group in February 1891. A cyclone caused severe damage in 1894. In 1972, Cyclone Bebe severely damaged Funafuti. Cyclone Ofa had a major impact in early 1990. During the 1996–97 cyclone season, Cyclone Gavin, Hina, and Keli passed through Tuvalu.

Cyclone Bebe 1972

In 1972, Funafuti was hit by Cyclone Bebe. This cyclone caused sea water to bubble through the coral on the airfield, reaching a height of 4–5 feet. Waves broke over the atoll. Five people died, including two adults and a baby swept away by waves. Cyclone Bebe destroyed 95% of houses and trees. The storm surge created a wall of coral rubble about 10 miles long on the ocean side of Funafuti and Funafala. The cyclone submerged Funafuti, contaminating drinking water.

Cyclone Pam 2015

Before Cyclone Pam formed, high tides in February 2015 caused significant road damage in Tuvalu. Between March 10 and 11, tidal surges of 3–5 meters (10–16 feet) from the cyclone swept across Tuvalu's low-lying islands. The atolls of Nanumea, Nanumanga, Niutao, Nui, Nukufetau, Nukulaelae, and Vaitupu were affected. There was major damage to farms and buildings. The outer islands were hit hardest, with one island completely flooded. A state of emergency was declared on March 13. Water supplies on Nui were contaminated. About 45% of Tuvalu's nearly 10,000 people were displaced.

New Zealand began providing aid on March 14. The Red Cross started an emergency plan to help 3,000 people with essential items and shelter. Flights carrying supplies from Fiji began on March 17. Tuvalu's Prime Minister, Enele Sopoaga, said Tuvalu could handle the disaster and urged international relief to focus on Vanuatu. Taiwan, UNICEF, and Australia also sent aid.

By March 22, 71 families on Nui were displaced, living in evacuation centers or with other families. On Nukufetau, 76 people were displaced. Nui suffered the most damage, with 90% of crops lost on both Nui and Nukufetau. Nanumanga also had significant damage, with many houses flooded.

Tuvalu and Climate Change

Tuvalu became the 189th member of the United Nations in September 2000. Tuvalu's main priority at the UN is to highlight "climate change and the unique vulnerabilities of Tuvalu to its adverse impacts."

In 2002, Governor-General Tomasi Puapua told the United Nations General Assembly that efforts for sustainable development mean nothing to Tuvalu without serious action on global warming. He said Tuvalu is very exposed to these effects, being only three meters (10 feet) above sea level. He mentioned that people are already leaving Tuvalu because of rising seas. He urged industrialized countries to ratify the Kyoto Protocol and help Tuvalu adapt to climate change.

In 2007, Ambassador Pita told the United Nations Security Council that ocean warming is changing Tuvalu, killing coral reefs, affecting fish stocks, and increasing the threat of severe cyclones. He said that if people have to migrate, it would threaten Tuvalu's nationhood and fundamental rights.

In 2008, Prime Minister Apisai Ielemia told the UN General Assembly that climate change is the most serious threat to global security. He stressed that human actions are needed to address it. He said that without urgent action to reduce greenhouse gases and adapt, the impact of climate change will be "catastrophic."

In November 2011, Tuvalu was a founding member of the Polynesian Leaders Group. This group works together on issues like culture, education, climate change, and trade. Tuvalu is also part of the Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS), which focuses on climate change concerns. The Sopoaga Ministry promised to use 100% renewable energy by 2020.

In September 2013, Prime Minister Enele Sopoaga said that moving Tuvaluans to avoid sea level rise "should never be an option." He urged people to talk to their lawmakers about their moral obligation to do the right thing.

At the 2015 United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP21), Prime Minister Sopoaga said the goal should be to limit global temperature rise to below 1.5 degrees Celsius. He said that Tuvalu's future is already difficult with current warming, and any further increase would mean its "total demise." He concluded with a plea: "Let's do it for Tuvalu. For if we save Tuvalu we save the world."

In November 2022, Simon Kofe, Tuvalu's Minister for Justice, Communication & Foreign Affairs, announced that Tuvalu would upload itself to the metaverse. This is an effort to preserve the country and allow it to function even if it goes underwater due to rising sea levels.

On November 10, 2023, Tuvalu signed the Falepili Union with Australia. Under this agreement, Australia will allow Tuvaluans to migrate there, helping with climate-related mobility.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Tuvalu para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Tuvalu para niños

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |