History of the Huns facts for kids

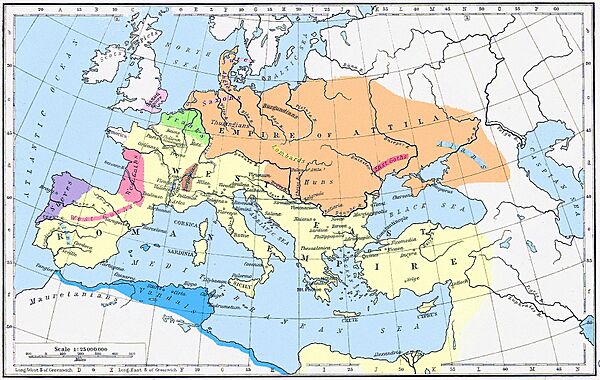

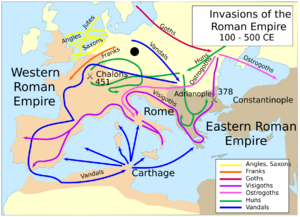

The Huns were a powerful group of nomadic warriors who arrived in Europe around 370 AD. They came from Central Asia and quickly became famous for their fierce fighting style. When they first appeared, they conquered tribes like the Goths and Alans. This forced many of these tribes to seek safety inside the Roman Empire.

Over the next few years, the Huns took control of most Germanic and Scythian tribes living outside the Roman Empire's borders. They also attacked Roman lands in Asia and the Sasanian Empire (ancient Persia) in 375.

Under their first known leader, Uldin, the Huns launched a big attack on the Eastern Roman Empire in Europe in 408, but it wasn't successful. Later, in the 420s, the Huns were led by brothers Octar and Ruga. They sometimes worked with the Romans and sometimes threatened them.

After Ruga died in 435, his nephews Bleda and Attila became the new Hunnic rulers. They successfully attacked the Eastern Roman Empire. They then made peace, getting a yearly payment and trading rights under the Treaty of Margus. Attila later killed his brother Bleda and became the sole ruler of the Huns in 445.

Attila ruled for eight more years. He launched a huge attack on the Eastern Roman Empire in 447, then invaded Gaul (modern France) in 451. People often say Attila was defeated in Gaul at the Battle of the Catalaunian Fields. However, some historians think it was a tie or even a Hunnic victory. The next year, the Huns invaded Italy and faced little resistance before turning back.

The Huns' control over Europe's barbarian tribes is thought to have ended suddenly after Attila's death, which happened the year after the Italy invasion. The Huns themselves are usually believed to have disappeared after his son Dengizich died in 469. Some historians, though, believe that the Bulgars might have been connected to the Huns. The Huns might have also played a role in the fall of the Western Roman Empire.

Contents

Where Did the Huns Come From?

Some historians believe the Huns came from an ancient group called the Xiongnu, who lived in China. However, there's no full agreement on this. There's a gap of about 200 years between when the Xiongnu disappeared from Chinese records and when the Huns showed up in European writings.

Archaeology hasn't found many clear links between the Huns' tools and items and those from Eastern Central Asia. Recent studies of ancient DNA from the Hunnic period in Europe show that some people had European connections, while others had Northeast Asian connections, similar to groups like the Xiongnu.

An ancient mapmaker named Ptolemy mentioned a group called the Khounoi in the 2nd century AD. They lived in the western part of the Eurasian steppe. Some scholars think this might be a very early mention of the Huns. But others believe the name similarity is just a coincidence.

The Huns' Early Adventures

First Big Victories

The Huns appeared suddenly in history. This suggests they crossed the Volga River from the east not long before. We don't know exactly why they attacked their neighbors so suddenly. One idea is that climate change dried up their grazing lands further east. Another idea is that a different nomadic group pushed them westward. A third idea is that they wanted to get closer to the rich Roman Empire to gain wealth.

The Romans first learned about the Huns when thousands of Goths moved to the Lower Danube in 376. These Goths were fleeing the Huns' invasion of the Pontic steppes. There are also signs that the Huns were raiding areas near the Caucasus Mountains in the 360s and 370s. These raids eventually made the Eastern Roman Empire and the Sasanian Empire work together to defend the mountain passes.

The Huns first attacked the land of the Alans, located east of the Don River. They defeated the Alans, forcing the survivors to join them or flee. Some historians believe the Huns didn't directly conquer them but instead formed alliances with some Alan groups. An old historian named Jordanes said the Huns also conquered other tribes near the Maeotian Swamp. These were likely Turkic-speaking nomadic tribes who later lived under the Huns along the Danube.

Jordanes claimed the Huns were led by a king named Balamber at this time. Some historians doubt he existed, but agree the Huns were a very large force.

After taking control of the Alans, the Huns and their Alan allies began to raid the rich settlements of the Greuthungi (eastern Goths) west of the Don. The Greuthungic king, Ermanaric, fought back for a while but eventually took his own life. His great-nephew, Vithimiris, took over. Vithimiris hired Huns to fight Alans who invaded his land, but he was killed in battle. Some historians think the Huns then turned on the weakened Goths and conquered them too.

After Vithimiris died, most Greuthungi joined the Huns. They kept their own king, Hunimund, whose name means "protected by the Huns." Those who resisted moved to the Dniester River, the border between the Greuthungi and the Thervingi (western Goths). They were led by Alatheus and Saphrax. Athanaric, the Thervingi leader, met the refugees at the Dniester. However, a Hun army went around the Goths and attacked them from behind, forcing Athanaric to retreat. Hun raids continued.

Most Thervingi realized they couldn't fight the Huns. They went to the Lower Danube and asked the Roman Empire for safety. The resisting Greuthingi also marched to the river. Most Roman soldiers were fighting in Armenia. Emperor Valens allowed the Thervingi to cross the Lower Danube and settle in the Roman Empire in autumn 376. The Greuthingi, Taifali, and other tribes followed. Food shortages and mistreatment led the Goths to revolt in early 377. The war between the Goths and Romans lasted over five years.

First Meetings with Rome

During the Gothic War, the Goths seemed to team up with some Huns and Alans. This group crossed the Danube and made the Romans let the Goths move deeper into Thrace. The Huns are mentioned as allies until 380, when they likely returned beyond the Danube. Also, in 381, the Sciri and Carpi, with some Huns, attacked Pannonia but failed.

Once Eastern Roman Emperor Theodosius I made peace with the Goths in 382, a historian named Eunapius said he gave them land and cattle. This was to create a "strong defense against the Huns." After this, the Huns reportedly raided Scythia Minor in 384 or 385. Soon after, in 386, a group of Greuthungi fled the Huns into Thrace. This was the last major migration into Roman land until after the Huns' rule ended. This suggests the Huns were firmly in control of the tribes outside Rome at this time.

Some historians believe the Huns already controlled large parts of Pannonia (modern Hungary) as early as 384. Others suggest they might have settled there as Roman allies, not invaders, around 380. In 384, a Roman general named Flavius Bauto used Hunnic soldiers to defeat the Juthungi tribe. However, the Huns then rode into Gaul instead of going home. Bauto had to pay them to turn back. They then attacked the Alamanni.

A writer named Pacatus Drepanius reported that the Huns fought with Theodosius against a rebel leader in 388. But in 392, the Huns were again raiding the Balkans with other tribes. Some Huns seemed to have settled in Thrace. Theodosius used these Huns as helpers in 394. Some think the Romans hoped to use the Huns against the Goths. These Huns were eventually wiped out by the Romans in 401 after they started stealing from Roman lands.

Big Attacks on Rome and Persia

In 395, the Huns began their first large-scale attacks on the Romans. In the summer, they crossed the Caucasus Mountains. In the winter of 395, another Hunnic force crossed the frozen Danube, robbed Thrace, and threatened Dalmatia. These two attacks were probably not planned together.

The Hun forces in Asia invaded Armenia, Persia, and Roman provinces in Asia. One group crossed the Euphrates River but was defeated by a Roman army. Two other armies, led by Basich and Kursich, rode down the Euphrates and threatened the Persian capital, Ctesiphon. One of these armies was defeated by the Persians, while the other successfully retreated. A final group of Huns destroyed parts of Asia Minor. The Huns caused great damage in Syria and Cappadocia, even threatening Antioch. The damage was worse because most Roman soldiers had been moved to the West due to Roman power struggles. In 398, a Roman official named Eutropius finally gathered an army and brought order back. It seems the Huns left on their own, without Eutropius defeating them in battle.

These larger attacks on Asia Minor and Persia suggest that most Huns stayed on the Pontic steppes at this time, rather than moving into Europe. It's clear the Huns didn't want to conquer or settle these lands. They wanted to steal goods, including cattle. A later writer, Priscus, heard from Huns that the raid was caused by a famine on the steppes. This might also explain the raids into Thrace.

Hunnic attacks on Armenia continued after this raid. Armenian sources mention a Hunnic tribe called the Xailandur as the attackers.

Uldin, a Hunnic Leader

Uldin was the first Hun leader known by name in Roman records. He was identified as the leader of Huns in Muntenia (modern Romania) in 400. We don't know how much land or how many Hun tribes Uldin controlled, but he clearly had power in parts of Hungary and Muntenia. The Romans called him a "sub-king," and he boasted of his great power.

In 400, a rebellious Roman general named Gainas fled into Uldin's territory with an army of Goths. Uldin defeated and killed him, sending Gainas's head to Constantinople. Some historians think Uldin wanted to work with the Romans while he expanded his control over Germanic tribes in the West. In 406, pressure from the Huns seems to have caused groups of Vandals, Suebi, and Alans to cross the Rhine into Gaul. Uldin's Huns raided Thrace in 404–405.

Also in 405, a group of Goths under Radagaisus invaded Italy. Some historians believe these Goths came from Uldin's territory, likely fleeing from him. Stilicho, a Roman general, asked Uldin for help. Uldin's Huns then destroyed Radagaisus's army in Tuscany in 406. Uldin may have done this to show he could destroy any barbarian groups trying to escape Hunnic rule. An army of 1,000 of Uldin's Huns also helped the Eastern Roman Empire fight against the Goths under Alaric. However, after Stilicho died in 408, Uldin switched sides and began helping Alaric.

Also in 408, the Huns, led by Uldin, crossed the Danube and captured an important fort called Castra Martis. The Roman commander in Thrace tried to make peace, but Uldin refused and demanded a very high payment. However, many of Uldin's commanders then left him and joined the Romans, who had bribed them. It seems most of his army was actually made up of Sciri and Germanic tribes, whom the Romans later sold into slavery. Uldin himself escaped back across the Danube and is not mentioned again. The Romans responded by strengthening their border defenses and the walls of Constantinople.

During this time, probably between 405 and 408, Flavius Aetius, who would later become a famous Roman general and Attila's opponent, lived among the Huns as a hostage.

The 410s

Information about the Huns after Uldin is scarce. In 412 or 413, a Roman statesman named Olympiodorus of Thebes was sent on a mission to "the first of the kings" of the Huns, Charaton. Olympiodorus wrote about this event, but only parts of his writing survive. Olympiodorus was sent to make peace with Charaton after a person named Donatus was "unlawfully put to death." Historians have thought Donatus was a Hunnic king. However, some argue that because his name was Roman, Donatus was likely a Roman who lived among the Huns. We don't know where Olympiodorus met Charaton. In 412, the Huns also launched a new raid into Thrace.

The Huns' United Rule

Ruga and Octar

The Huns raided again in 422, seemingly led by a chief named Ruga. They reached as far as the walls of Constantinople. They seem to have forced the Eastern Roman Empire to pay them a yearly tribute. In 424, they were noted fighting for the Romans in North Africa, showing they had friendly relations with the Western Roman Empire. In 425, the Roman general Aetius marched into Italy with a large Hunnic army to fight against forces from the Eastern Empire. The conflict ended peacefully, and the Huns received gold before returning home. In 427, however, the Romans broke their alliance with the Huns and attacked Pannonia, perhaps taking back some land.

It's not clear when Ruga and his brother Octar became the top rulers of the Huns. Ruga seems to have ruled the land east of the Carpathians, while Octar ruled the area to the north and west of the Carpathians. Some historians believe Octar was a "deputy" king under Ruga, who was the supreme king. Octar died around 430 while fighting the Burgundians, who lived near the Rhine River at the time. Some historians think his nephew Attila likely took his place as ruler of the eastern part of the Hunnic empire that year.

In 432, Ruga helped Aetius, who had lost favor, get his important general's office back. Ruga either sent or threatened to send an army into Italy. In 433, Aetius gave a region called Pannonia Prima to Ruga, perhaps as a reward for the Huns' help. In 434, Ruga sent a messenger to Constantinople, saying he planned to attack some tribes who had fled into Roman territory. However, he died after this campaign began, and the Huns left Roman land.

Attila and Bleda Take Over

After Ruga's death, his nephews Attila and Bleda became the rulers of the Huns. Bleda seems to have ruled the eastern part of the empire, while Attila ruled the west. Some historians believe Bleda was the main king of the two. In 435, Bleda and Attila forced the Eastern Roman Empire to sign the Treaty of Margus. This treaty gave the Huns trading rights and increased the yearly payment from the Romans. The Romans also agreed to hand over Hunnic refugees and runaway tribes.

Ruga had promised to help Aetius in Gaul before he died, and Attila and Bleda kept this promise. In 437, Huns, guided by Aetius and possibly with Attila's involvement, destroyed the Burgundian kingdom on the Rhine. This event is remembered in old Germanic stories. It's possible the Huns destroyed the Burgundians to get revenge for Octar's death in 430. Also in 437, the Huns helped Aetius capture Tibatto, the leader of the Bagaudae, a group of rebellious peasants and slaves. In 438, a Hun army helped the Roman general Litorius in an unsuccessful attack on the Visigothic capital of Toulouse.

In 440, the Huns attacked the Romans during one of the yearly trading fairs agreed upon in the Treaty of Margus. The Huns said they did this because the bishop of Margus had entered Hunnic land and robbed Hunnic royal tombs. They also claimed the Romans broke the treaty by protecting refugees from the Hunnic empire. When the Romans didn't hand over the bishop or the refugees by 441, the Huns attacked many towns and captured the city of Viminacium, burning it to the ground. The bishop of Margus, scared he would be given to the Huns, made a deal to betray the city to them, and it was also burned. The Huns also captured a fort on the Danube and destroyed the cities of Singidunum and Sirmium. After this, the Huns agreed to a truce.

In 444, tensions grew between the Huns and the Western Roman Empire. The Romans prepared for war. However, the problems seemed to be solved the next year through diplomacy. The Romans likely gave some land to the Huns near the Sava River. Attila might have also been made a Roman general to receive a salary.

Attila Rules Alone

Bleda died sometime between 442 and 447, most likely in 444 or 445. It seems Attila murdered him. After Bleda's death, a tribe called the Akatziri either rebelled against Attila or had never been under his rule. Some historians suggest they rebelled because of Bleda's death, as they were probably more loyal to him. The Romans encouraged this rebellion by sending gifts to the Akatziri. However, the Romans offended the Akatziri's main chief by giving him gifts second instead of first. He then asked Attila for help against the other rebellious leaders. Attila's forces defeated the tribe after several battles. The chief was allowed to rule his own tribe, but Attila put his own son Ellac in charge of the rest of the Akatziri.

Sometime after Bleda's death, while the Huns were busy with their own issues, the Roman Emperor Theodosius stopped paying the agreed tribute to the Huns. In 447, Attila sent a message to complain, threatening war. He said his people were unhappy and some had even started raiding Roman territory. The Romans refused to restart the payments or hand over any refugees. So, Attila began a full-scale attack by capturing the forts along the Danube. His forces included not only Huns, but also tribes he controlled, like the Gepids (led by King Ardaric) and the Goths (led by King Valamer), among others.

After clearing the Danube of Roman defenses, the Huns marched westward. They defeated a large Roman army at the Battle of the Utus. The Huns then robbed and burned Marcianople. The Huns then headed for Constantinople itself. Its walls had been partly destroyed by an earthquake earlier that year. The people of Constantinople managed to rebuild the walls before Attila's army arrived. However, the Romans suffered another major defeat. The Huns continued to raid as far south as Thermopylae and captured most of the major towns in the Balkans, except for Hadrianople. Theodosius was forced to ask for peace. Besides the tribute the Romans had failed to pay before, the yearly payment was increased. The Romans also had to give up a large area of land south of the Danube to the Huns, leaving the border unprotected.

In 450, Attila made a new treaty with the Romans and agreed to leave Roman lands. Some historians believe this was so he could plan an invasion of the Western Roman Empire. According to Priscus, Attila also thought about invading Persia at this time. The new emperor, Marcian, soon broke the treaty with Constantinople. However, Attila was already busy with his plans for the Western Empire and didn't react.

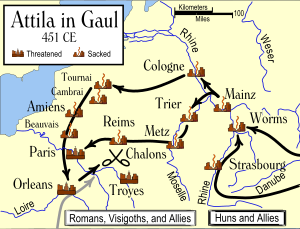

Invasion of Gaul

In the spring of 451, Attila invaded Gaul. Relations with the Western Roman Empire had already gotten worse by 449. One of the leaders of the Bagaudae, Eudoxius, had also fled to the Huns in 448. Aetius and Attila had also supported different people to be king of the Ripuarian Franks in 450. Attila told the East Roman messengers in 450 that he planned to attack the Visigoths as an ally of the Western Emperor Valentinian III.

According to one story, Honoria, the sister of Valentinian III, sent Attila a ring and asked for his help to escape being held captive by her brother. Attila then demanded half of Western Roman territory as her dowry and invaded. Many historians doubt this story, calling it "ridiculous." Another historian claims that Geiseric, king of the Vandals in North Africa, encouraged Attila to attack. Some think Attila wanted to remove Aetius and take his honorary Roman general title. Others believe Attila didn't really want to conquer Gaul, but rather to secure his control over Germanic tribes living near the Rhine.

The Hunnic army left the Hungarian Plain and likely crossed the Rhine near Koblenz. The Hunnic army included Huns, Gepids, Rugii, Sciri, Thuringi, and Ostrogoths. They captured Metz and Trier, then went to attack Orléans. Another group unsuccessfully attacked Paris. The arrival of Aetius' army, which included Romans and allies like the Visigoths (led by King Theodoric I), Burgundians, Alans, and some Franks, forced the Huns to stop their attack on Orléans.

Near Troyes, the two armies met and fought in the Battle of the Catalaunian Fields. Most historians believe that despite the death of Theodoric, Attila's army was defeated and forced to leave Gaul. However, some argue that the battle was actually a Hunnic victory. They say the Huns were already leaving Gaul after a successful campaign and simply continued to do so after the battle.

Invasion of Italy

After returning to Pannonia, Attila ordered raids into Illyricum to make the Eastern Roman Empire start paying tribute again. However, instead of attacking the Eastern Empire, in 452 he invaded Italy. The exact reasons are unclear. One old record says it was because he was angry about his defeat in Gaul the year before.

The Huns crossed the Julian Alps and then attacked the heavily defended city of Aquileia. They eventually captured and burned it after a long siege. They then entered the Po Valley, robbing Padua, Mantua, Vicentia, Verona, Brescia, and Bergamo. Then they attacked and captured Milan. The Huns did not try to capture Ravenna, and they either stopped or did not try to take Rome. Aetius could not offer much resistance, and his power was greatly weakened. The Huns met with a peace group led by Pope Leo I and eventually turned back.

Some historians believe that a combination of disease and an attack by Eastern Roman troops on the Hunnic homeland in Pannonia led to the Huns' withdrawal. Others argue that the Eastern Roman attacks are made up, as the Eastern Empire was in a worse state than the West. They believe the campaign was a success and the Huns simply left after getting enough loot.

After Attila's Death

The Hunnic Empire Falls Apart

In 453, Attila was reportedly planning a major campaign against the Eastern Romans to force them to pay tribute again. However, he died unexpectedly, supposedly from bleeding during his wedding to a new bride. He might also have been planning an invasion of the Sasanian Empire.

According to Jordanes, Attila's death led to a power struggle among his sons. We don't know how many there were, but old sources name three: Ellac, Dengizich, and Ernak. The brothers started fighting each other, which caused the Gepids under Ardaric to rebel. The Huns under Ellac then fought the Gepids and were defeated, leading to Ellac's death. This happened at the Battle of Nedao in 454. Some historians think there might have been more than one battle. Some tribes, like the Sciri, fought on the Huns' side against the Gepids. The end of Hunnic rule was a slow process, as the Huns gradually lost control over the tribes they had conquered.

The Huns continued to exist under Attila's sons Dengizich and Ernak. Some historians believe Dengizich successfully rebuilt Hunnic rule over the western part of their empire by 464. In 466, Dengizich demanded that Constantinople start paying tribute to the Huns again and restore their trading rights with the Romans. The Romans refused. Dengizich then decided to invade the Roman empire. Ernak chose not to join him, focusing on other wars. Without his brother, Dengizich had to rely on the recently conquered Ostrogoths and the "unreliable" Bittigur tribe. His forces also included other Hunnic tribes. The Romans managed to make the Goths in his army revolt, forcing Dengizich to retreat. He died in 469. Some believe he was murdered, and his head was sent to the Romans. This marked the end of Hunnic rule in the West.

Germanic Tribes After the Huns

Some historians argue that the most important barbarian leaders in Europe after Attila were actually Huns themselves or were closely linked to Attila's empire. For example, Ardaric, the Gepid leader who rebelled, is sometimes thought to have been a Hun. His grandson, Mundo, is called both a Hun and a Gepid in old writings. This idea suggests that Gepid rule in the Carpathian Basin was similar to that of the Huns.

The Sciri also came out of Attila's empire with a possibly Hunnic king. Edeco is first mentioned as Attila's messenger. His sons, Hunoulph and Odoacer, who later conquered Italy, might also have been Huns, even though the armies they led were mostly Germanic.

The Goths led by the Amali dynasty also became independent sometime after 454. However, some Goths continued to fight with the Huns as late as 468. Some historians argue that even the Amali-led Goths remained loyal to the Huns until later, when their leader made an alliance with the Romans.

Huns in the East

It's unclear what happened to Attila's youngest son, Ernak. Some historians say Ernak and a group of Huns settled in northern Dobruja with Roman permission. The rulers of the Bulgars, a Turkic nomadic people who first appeared around 480, might have claimed to be descended from Attila through Ernak. Some historians believe Ernak combined the remaining Huns with new Turkic tribes to form the Bulgars.

Old sources seem to show that not all Hunnic peoples joined Ernak's Bulgar state. Huns continued to appear as soldiers for hire and allies of both the Persians and Romans in the 6th century. The Hunnic Altziagiri tribes continued to live in the Crimea.

A final possible group of Huns are the North Caucasian Huns, who lived in what is now Dagestan. It's not clear if these Huns were ever under Attila's rule. They raided Persia in 503 and are recorded raiding Armenia and other areas in 515. The Romans hired soldiers from this group. At some point, the North Caucasian Huns became a vassal state of the Khazar Khaganate. They are recorded to have become Christian in 681. The North Caucasian Huns are last mentioned in the 7th century, but they might have continued to exist within the Khazar empire.

What Was the Huns' Impact?

The Huns, and the movements of people linked to them, changed the Western Eurasian steppe. It went from being mainly home to Iranian-speaking nomads to Turkic-speaking ones, as Turkic speakers moved west from modern Mongolia.

In Europe, the Huns are often seen as the start of the Migration period. During this time, mostly Germanic tribes moved more and more into the late Roman Empire. Some historians argue that the Huns were responsible for the eventual fall of the Western Roman Empire. Others believe the Huns sped up Germanic attacks both before and after their own presence on the Roman border. One historian notes that "what the Huns had achieved was a massive transfer of resources from the Roman empire to the barbarian lands."

Some scholars see the Huns as less important in the end of Rome. One described the Huns under Attila as "for a few years more than a nuisance to the Romans, though at no time a real danger." Other scholars have even argued that the Huns held back the Germanic tribes and thus gave the Roman Empire a few more years of life.

|