Markhor facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Markhor |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Markhor in Tierpark Berlin, Germany | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Subfamily: | |

| Genus: | |

| Binomial name | |

| Capra falconeri |

|

The markhor (Capra falconeri), also known as the screw horn goat, is a large type of wild goat. You can find it in mountainous areas of northeastern Afghanistan, northern and central Pakistan, Northern India, southern Tajikistan, southern Uzbekistan, and the Himalayas.

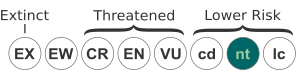

The markhor was once considered an endangered animal. But since 2015, its numbers have grown by about 20% over the last ten years. Because of this, it is now listed as "Near Threatened". The markhor is also the national animal of Pakistan.

Contents

What's in a Name?

Why is it Called Markhor?

Some people think the name markhor comes from two Persian words: mar, meaning "snake", and khor, meaning "eater". This might mean the markhor can kill snakes. Or it could be because its twisted horns look a bit like coiling snakes.

There's a folk tale that says the markhor can kill a snake. After it chews its food, a foamy substance comes out of its mouth. Local people collect this foam when it dries. They believe it can help remove poison from snakebites.

Local Names for the Markhor

The markhor has many different names depending on the local language:

- Balti: Reedakh

- Persian, Urdu, Punjabi, and Kashmiri: مارخور markhor

- Pashto: مرغومی marǧūmay

- Ladaki: rache, rapoche (male) and rawache (female)

- Burushaski: boom (Markhor), boom haldin (male), giri haldin (female)

- Shina: boom mayaro, (male) and boom mayari (female)

- Brahui: rezkuh, matt (male) and hit, harat (female)

- Baluchi: pachin, sara (male) and buzkuhi (female)

- Wakhi: youksh, ghashh (male) and moch (female)

- Khowar/Chitrali: sara (male) and maxhegh (female)

Appearance and Features

Markhor are quite large. They stand about 65 to 115 centimeters (25 to 45 inches) tall at the shoulder. They can be 132 to 186 cm (52 to 73 in) long and weigh from 32 to 110 kilograms (70 to 240 pounds). They are the tallest wild goats in their group, but the Siberian ibex can be longer and heavier.

Their fur is a mix of light brown and black, giving them a grizzled look. In summer, their coat is short and smooth. In winter, it grows longer and thicker to keep them warm. Their lower legs have black and white fur.

Male and female markhor look different, which is called sexual dimorphism. Males have longer hair on their chin, throat, chest, and legs. Females are more reddish in color, with shorter hair and a small black beard. Both male and female markhor have unique, corkscrew-like horns. These horns start close together at the head and then twist upwards. Male horns can grow very long, up to 160 cm (63 in), while female horns are shorter, up to 25 cm (9.8 in). Male markhor also have a strong, distinct smell.

Markhor Behavior

Markhor are well-suited for life in the mountains. They live at high elevations, from 600 to 3,600 meters (2,000 to 11,800 feet). They usually live in forests with oaks, pines, and juniper trees.

They are active during the day, mostly in the early morning and late afternoon. Their diet changes with the seasons. In spring and summer, they mostly eat grass. In winter, they eat leaves and twigs from trees, sometimes standing on their back legs to reach higher branches.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

The mating season for markhor is in winter. During this time, male markhor fight by lunging at each other, locking horns, and trying to push their opponent off balance. A female markhor is pregnant for about 135 to 170 days. She usually gives birth to one or two young, called kids, but sometimes three.

Markhor live in groups, usually with about nine animals. These groups are made up of adult females and their young. Adult males mostly live alone. Females and their kids make up the largest part of the markhor population. When markhor sense danger, their alarm call sounds a lot like a domestic goat's bleating.

Early in the season, males and females might be seen together in open grassy areas. But in summer, males tend to stay in the forest, while females usually climb to the highest rocky ridges.

Types of Markhor

Over the last 150 years, different types of markhor have been identified. These types were often based on the shape of their horns. However, we now know that horn shapes can vary a lot, even among markhor living in the same mountain range.

Here are some of the recognized types of markhor:

- Astor or Astore markhor (Capra falconeri falconeri)

- Bukharan markhor (Capra falconeri heptneri)

- Kabul markhor (Capra falconeri megaceros)

- Kashmir markhor (Capra falconeri cashmiriensis)

- Suleiman markhor (Capra falconeri jerdoni)

It's important to know that the Chiltan ibex (Capra aegagrus chialtanensis) is not a markhor. It's actually a type of Bezoar ibex.

Astor Markhor

The Astor markhor has large, flat horns that spread out wide and then go almost straight up with a half-twist. This type is also known as the Pir Panjal markhor, which has heavy, flat horns twisted like a corkscrew.

In Afghanistan, you can find the Astor markhor in the high, mountainous forests of Laghman and Nuristan. In India, this markhor lives in parts of the Pir Panjal Range in southwestern Jammu and Kashmir. In Pakistan, the Astor markhor lives along the Indus River and its smaller rivers, as well as the Kunar River and its branches. The biggest group of Astor markhor is currently found in Chitral National Park in Pakistan.

Bukharan Markhor

The Bukharan markhor used to live in many mountains from Turkmenistan to Tajikistan. Now, only a few scattered groups remain. They are found in Tajikistan near Kulyab and in the Kugitangtau Range in Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan. This type might also exist in northern Afghanistan, near the border with Tajikistan.

Kabul Markhor

The Kabul markhor has horns with a slight corkscrew twist.

In Afghanistan, the Kabul markhor used to live in the Kabul Gorge and the Kohe Safi area. Now, due to a lot of illegal hunting, they only live in the hardest-to-reach parts of the mountains in Kapissa and Kabul Provinces. In Pakistan, they are found in small, separate areas in Baluchistan, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK) province, and Dera Ghazi Khan District in Punjab Province. About 100 of these animals are thought to live on the Pakistani side of the Safed Koh mountain range.

Markhor and Domestic Goats

Some scientists believe that the markhor is an ancestor of certain types of domestic goats. For example, the Angora goat is thought by some to be directly related to the Central Asian markhor. Charles Darwin even suggested that modern goats came from markhor crossbreeding with wild goats. There is evidence that markhor can crossbreed with domestic goats.

Some studies have shown that some markhor in zoos have DNA from domestic goats. Other scientists think markhor might be ancestors of some Egyptian goat breeds because their horns look similar. The Changthangi domestic goat from Ladakh and Tibet might also come from the markhor. The Girgentana goat from Sicily and the Bilberry goat from Ireland are also thought to have markhor ancestors. There's even a group of about 200 feral goats on the Great Orme in Wales that came from a herd kept by Queen Victoria at Windsor Great Park.

Studies of markhor and domestic goat droppings show that these two species compete a lot for food. This competition for food between plant-eating animals is believed to have greatly reduced the amount of food available in the Himalaya-Karkoram-Hindukush mountains. Domestic animals often have an advantage because their large herds can push wild animals out of the best grazing areas. Less food can also negatively affect how many young female markhor can have.

Who Hunts Markhor?

Humans are the main hunters of markhor. Because markhor live in very steep and hard-to-reach mountains, some groups of markhor have rarely been seen by people. Golden eagles have been seen hunting young markhor.

Wild animals that hunt markhor include Himalayan lynx, leopard cats, snow leopards, wolves, and Asian black bears. Because of these dangers, markhor have excellent eyesight and a strong sense of smell to spot predators nearby. They are very aware of their surroundings and are always on the lookout for danger. In open areas, they quickly spot predators and run away.

Threats to Markhor

Besides natural predators, markhor face other serious threats. Hunting for meat or for selling animal parts is a big problem in many countries. Poaching, which is illegal hunting, is the most important threat to markhor survival. Poaching also disturbs the markhor and makes them flee, reducing the size of their safe habitat. The main poachers seem to be local people, border guards, and Afghans crossing the border illegally. Poaching breaks up markhor groups into small, isolated populations, which are more likely to die out.

The markhor's unique spiral horns are highly valued as a hunting trophy. This has also become a threat to their species. The continued decline of markhor populations eventually caught the attention of the international community.

Hunting Regulations

In British India, hunting markhor was considered one of the most difficult sports because of the dangerous mountain terrain.

It is illegal to hunt markhor in Afghanistan. However, they have been traditionally hunted in Nuristan and Laghman Provinces. This hunting might have increased during the War in Afghanistan. In Pakistan, hunting markhor is legal as part of a conservation plan. Expensive hunting licenses are sold by the Pakistani government. These licenses allow hunters to target older markhor that are no longer able to breed. In India, it is illegal to hunt markhor. However, they are still poached for food and for their horns, which some people believe have medicinal properties.

Markhor have also been brought to private game ranches in Texas, USA. However, unlike some other animals like the aoudad or blackbuck, markhor have not escaped in large enough numbers to create wild populations there.

Protecting the Markhor

The International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) currently lists the markhor as a "Near Threatened" species. This is because their population is relatively small (estimated at about 5,800 individuals in 2013). However, their numbers are not expected to decline overall, thanks to ongoing conservation efforts.

In Tajikistan, there are two protected areas for markhor. The Dashtijum Strict Reserve, established in 1973, protects markhor across 20,000 hectares (49,000 acres). The Dashtijum Reserve covers 53,000 hectares (130,000 acres). Even though these reserves exist, the rules are often not strictly followed, leading to common poaching and habitat destruction.

Despite these challenges, recent studies show that conservation efforts have been very successful. This approach started in the 1900s when a local hunter was convinced by a tourist to stop poaching markhor. This hunter then started a conservation group, which inspired two other local organizations called Morkhur and Muhofiz. These groups hope to not only protect the markhor but also use the species in a sustainable way. This local approach has been more effective than protected lands where rules are not enforced. In India, the markhor is a fully protected species under Jammu and Kashmir’s Wildlife (Protection) Act of 1978.

Markhor in Culture

The markhor is the national animal of Pakistan. In 1976, it was one of 72 animals featured on the WWF Conservation Coin Collection. Markhor puppets are used in Afghan puppet shows called buz-baz. The markhor was also mentioned in a Pakistani computer-animated film called Allahyar and the Legend of Markhor.

In 2018, Pakistan's main airline, Pakistan International Airlines, put the markhor on its new airplane design. The Markhor is also part of the logo for the Inter-Services Intelligence, which is Pakistan's main intelligence agency.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Marjor para niños

In Spanish: Marjor para niños

| Frances Mary Albrier |

| Whitney Young |

| Muhammad Ali |