Maryland in the American Revolution facts for kids

Maryland started as a British colony in 1632. It was founded by Sir George Calvert as a safe place for English Catholics. His son, Cecilius Calvert, sent the first settlers to the Chesapeake Bay in 1634.

The first signs of trouble with Britain appeared in 1765. A tax collector named Zachariah Hood was hurt in Annapolis. This was one of the first violent protests against British taxes in the colonies. After many arguments, Maryland declared itself an independent state in 1776. It was one of the Thirteen Colonies to break away from Great Britain. Maryland signed the Declaration of Independence in Philadelphia. Important Marylanders who signed were Samuel Chase, William Paca, Thomas Stone, and Charles Carroll of Carrollton.

Even though no major battles of the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783) happened in Maryland, its soldiers were very brave. General George Washington praised the "Maryland Line" regiment. They fought in the Continental Army, especially the famous "Maryland 400" at the Battle of Brooklyn in 1776. Maryland is still known as "The Old Line State" because of them.

During the war, Baltimore was the temporary capital of the colonies. The Second Continental Congress met there from December 1776 to February 1777. This happened because Philadelphia was in danger from the British. Later, from November 1783 to June 1784, Annapolis became the capital of the new United States of America. It was in the Maryland State House in Annapolis that General George Washington famously gave up his role as commander-in-chief on December 23, 1783. Also, the Treaty of Paris, which ended the war, was approved there on January 14, 1784.

Maryland was divided during the war. Many Loyalists (people loyal to Britain) lost their lands. The powerful Barons Baltimore also lost their influence. A new group of leaders, loyal to the new American government, took their place.

Contents

Maryland's Early Days

Maryland began as the Province of Maryland, an English settlement in North America. It was founded in 1632 by George Calvert, 1st Baron Baltimore. He wanted to create a safe place for English Catholics in the New World. After he died in 1632, the land grant went to his son, Cecil Calvert, 2nd Baron Baltimore.

Cecil Calvert sent two ships, The Ark and The Dove, which landed on March 25, 1634, at St. Clement's Island. The settlers, led by Father Andrew White, held a religious service and set up a cross. In April 1634, Lord Baltimore's younger brother, Leonard Calvert, started a settlement called ""St. Mary's City"."

Religious Differences

Maryland was one of the first colonies to allow different religions. However, there were often conflicts between Anglicans, Puritans, Roman Catholics, and Quakers. In 1644, Puritan rebels even took control of the province for a short time.

In 1688, King James II was replaced by his Protestant daughter Mary and her husband William of Orange. In Maryland, John Coode led a rebellion. This rebellion removed the Catholic Lords Baltimore from power and stopped public Catholic worship. In 1692, the King appointed a new governor for Maryland.

How Maryland Made Money

Maryland's economy grew much like Virginia's. Early towns were built near rivers and waterways leading to the Chesapeake Bay. Like Virginia, Maryland's main crop was tobacco, which was sold in Europe. Growing tobacco needed many workers. This led to a quick increase in indentured servitude (people working to pay off debts) and, sadly, the forced enslavement of Africans.

Later, in the southern and eastern parts of Maryland, tobacco farming with slave labor continued. But in northern and central Maryland, farmers started growing more wheat. This helped towns like Frederick and the port city of Baltimore grow.

Money Troubles with Britain

One big problem between Maryland and Britain was about money. It was mainly about selling tobacco. A few merchants from Glasgow, Scotland, controlled most of the tobacco trade. They set prices and caused many problems for farmers in Maryland and Virginia. By the time the war started, these farmers owed huge amounts of money to British merchants. These debts made colonists very angry, even more than the taxes Britain imposed.

Before 1740, Glasgow merchants handled less than 10% of America's tobacco. But by the 1750s, they controlled more than all other British ports combined. These merchants were very rich and took big risks. They made huge fortunes by using fast ships and clever deals. They offered easy credit to Maryland farmers. This allowed farmers to buy European goods before they sold their crops. But when it was time to sell, the farmers had to accept low prices to avoid going bankrupt.

Farmers in Virginia faced similar issues. George Washington, who would become the first U.S. President, owed nearly £2000 by the late 1760s. Thomas Jefferson said British merchants unfairly lowered tobacco prices. He felt they forced farmers into debt they could never pay off.

Many Marylanders wanted to use the war as a chance to get rid of their debts. After the war, very few of these large debts were ever repaid.

There were also disagreements about land. In 1763, Britain decided to protect Native American land rights. This angered many colonists, including George Washington. He felt this decision was only temporary and would change once Native Americans agreed to give up their lands.

Protests Against Taxes

In 1764, Britain put a tax on sugar. This was one of many attempts to make the American colonies pay for the recent French and Indian War. The first signs of revolution in Maryland appeared in 1765. The Maryland Assembly received letters from Massachusetts. These letters suggested a meeting of all colonies to protest British taxes. They argued that Marylanders should only pay taxes they agreed to.

Around the same time, Zachariah Hood, an Annapolis merchant, was tasked with collecting the new stamp tax. When he returned to Maryland, an angry crowd attacked him at the dock. This was called the "first successful, forceful resistance in America to King George's authority." Hood was scared and fled to New York. The governor, Sharpe, reported that he feared the stamp paper would be burned if it arrived.

Charles Carroll of Carrollton

One important person who spoke up for independence in Maryland was Charles Carroll of Carrollton. He was a wealthy Roman Catholic farmer. In 1772, he debated in newspapers, arguing that the colonies should control their own taxes. As a Catholic, he couldn't hold political office, practice law, or even vote.

By the early 1770s, Carroll began to believe that only fighting could solve the problems with Britain. He once told Samuel Chase that arguments would only make people angry enough for war to be the answer.

Writing under the name "First Citizen" in the Maryland Gazette, Carroll spoke out against the governor's decision to raise legal fees. He also served on various Committees of Correspondence, which helped spread ideas about independence.

From 1774 to 1776, Carroll was part of the Annapolis Convention. In 1774, he was sent with Benjamin Franklin and others to seek help from Canada. He was also on Annapolis' first Committee of Safety in 1775. In 1776, he was elected to the Continental Congress. He arrived too late to vote for the Declaration of Independence, but he was able to sign it.

Some people believe the First Amendment to the United States Constitution, which guarantees freedom of religion, was created partly because of Carroll's financial support during the war. He was the only Roman Catholic to sign the Declaration of Independence, and he was the last signer alive when he died in 1832.

Samuel Chase

Samuel Chase (1741–1811) was a strong supporter of states' rights and a revolutionary. He signed the United States Declaration of Independence for Maryland. He helped start the Sons of Liberty group in Anne Arundel County with his friend William Paca. He also led protests against the 1765 Stamp Act. Later, he became a judge on the Supreme Court of the United States.

People Loyal to Britain

Before the war, people in Maryland had very different opinions. Many Marylanders supported the British King or did not want to use violence. In 1766, Samuel Chase argued with several Loyalist leaders in Annapolis. Chase called them "busy, reckless incendiaries" and "disturbers of the public peace." These arguments became more heated as the war got closer.

One important Loyalist was Daniel Dulaney the Younger. He was the Mayor of Annapolis and a respected lawyer. Dulany was against the Stamp Act 1765. He wrote a famous pamphlet called Considerations on the Propriety of Imposing Taxes in the British Colonies. In it, he argued against "taxation without representation." He believed that protests and legal discussions, not force, should solve America's problems. As war became certain, Dulany, like many others, had to choose a side. He could not rebel against the King he had served for so long.

The Revolution Begins

In 1774, committees of correspondence formed across the colonies. They offered support to Boston after Britain closed its port and sent more soldiers. Massachusetts asked for a general meeting, a Continental Congress, to plan joint action. To stop this, Maryland's royal governor, Sir Robert Eden, closed the Maryland colonial assembly on April 19, 1774. This was the last time the colonial assembly met in Maryland.

Annapolis Tea Party

On October 19, 1774, an angry crowd in Annapolis burned the Peggy Stewart, a Maryland cargo ship. They were punishing the ship's captain for breaking the boycott on tea imports. This event was similar to the more famous Boston Tea Party in December 1773, and it became known as the "Annapolis Tea Party."

Local stories also say that the Chestertown Tea Party happened in Chestertown, Maryland, in May 1774. Patriots supposedly threw tea from a ship into the Chester River to protest British taxes. This event is still celebrated today with a festival and re-enactment.

Governor Eden returned to Maryland after the Peggy Stewart was burned. In December 1774, he wrote that the desire to resist the Tea Act was "as strong and universal here as ever." He believed Marylanders would suffer any hardship rather than accept Britain's right to tax them.

Despite these protests, Maryland was still hesitant to declare full independence. It instructed its delegates to the First Continental Congress in September 1774 to hold back.

Assembly of Freemen

During the early part of the Revolution, Maryland was governed by the Assembly of Freemen. This was an assembly of representatives from the state's counties. The first meeting was from June 22 to June 25, 1774, with 92 members from all sixteen counties.

The Assembly decided that this temporary government was not enough. They needed a more permanent and organized government. So, on July 3, 1776, they decided to elect a new convention. This new convention would write Maryland's first state constitution. This constitution would not mention the King or Parliament. It would be a government "of the people only." On August 1, all property owners elected delegates for this final convention. This ninth convention, also called the Constitutional Convention of 1776, wrote the constitution. When they finished on November 11, they did not meet again. The new state government, created by the Maryland Constitution of 1776, took over. Thomas Johnson became Maryland's first elected governor.

Declaring Independence

Maryland declared independence from Britain in 1776. Samuel Chase, William Paca, Thomas Stone, and Charles Carroll of Carrollton signed the Declaration of Independence for Maryland.

In 1777, all Maryland voters had to take the Oath of Fidelity and Support. This oath meant swearing loyalty to Maryland and rejecting loyalty to Great Britain. It was signed by thousands of residents in Montgomery and Washington counties.

On March 1, 1781, the Articles of Confederation became law after Maryland approved them. The Articles were the first constitution of the United States. They had been proposed in 1777, but it took years to get all states to agree. Maryland was the last state to ratify. It refused until Virginia and New York gave up their claims to western lands.

Maryland later approved the United States Constitution more easily, ratifying it on April 28, 1788.

Maryland in the Revolutionary War

Even though no major battles happened in Maryland, its soldiers were very brave. General George Washington was very impressed with the Maryland soldiers, known as the "Maryland Line." They fought in the Continental Army. This is why Maryland is sometimes called "The Old Line State."

Maryland also played other important roles during the war. For example, the Continental Congress met in Baltimore from December 20, 1776, to March 4, 1777. Baltimore became the temporary capital when Philadelphia was threatened by the British. They met at the "Henry Fite House," a large brick building.

Marylander John Hanson served as President of the Continental Congress from 1781 to 1782. He was the first person to serve a full term as President under the Articles of Confederation.

From November 26, 1783, to June 3, 1784, Annapolis was the capital of the United States. The Confederation Congress met in the Maryland State House. It was in the old senate chamber that George Washington resigned his role as commander-in-chief on December 23, 1783. Also, the Treaty of Paris, which ended the Revolutionary War, was approved by Congress there on January 14, 1784.

Loyalists During the War

During the war, many Marylanders, like Benedict Swingate Calvert, stayed loyal to the British Crown. Calvert was the illegitimate son of the ruling Calvert family. He lost his political power when the old Maryland leaders were overthrown. Men like Calvert, Governor Eden, and George Steuart lost their power, and sometimes their land and wealth.

On May 13, 1777, Benedict Swingate Calvert had to give up his job as a judge. He worried about his family's safety and wanted to move them somewhere safe.

Calvert did not leave Maryland or fight in the war. He sometimes supplied the Continental Army with food. After the war, he had to pay triple taxes, like other Loyalists. But he was never forced to sign a loyalty oath, and his land was not taken away.

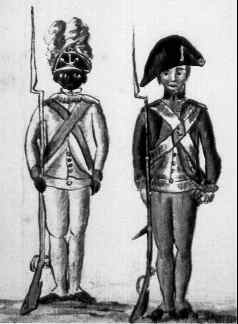

African Americans and the War

The main reason for the American Revolution was freedom, but this freedom was mostly for white men, not for enslaved people. The British needed more soldiers. They offered freedom to African American soldiers who would fight for the King. In 1775, the Royal Governor of Virginia, Lord Dunmore, promised freedom to servants and slaves who would join his Loyalist army.

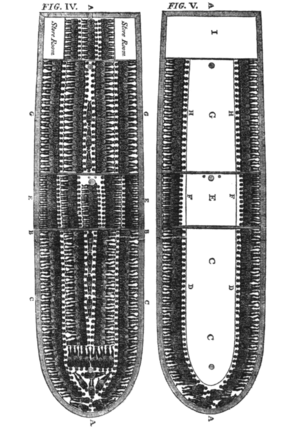

About 800 men joined. Some helped fight in battles, wearing the motto "Liberty to Slaves." However, many became sick with smallpox. The survivors joined other British units and fought throughout the war. Many Black people volunteered to fight for the British. This forced the American rebels to also offer freedom to those who would serve in the Continental Army. However, promises of freedom were often broken by both sides.

Overall, the war did not change slavery much in Maryland. The wealthy life of Maryland planters continued.

After the War

In 1783, Henry Harford, the last governor of Maryland appointed by the Calvert family, tried to get his lands back. These lands had been taken during the American Revolution. He was in Annapolis when George Washington resigned his command. However, he could not get his land back, even though Charles Carroll of Carrollton and Samuel Chase supported him. In 1786, the Maryland General Assembly decided the case. They rejected his claim because he was absent during the war and his father had angered the colonists.

Henry Harford returned to Britain and was given £100,000 as compensation.

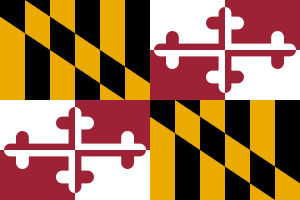

Some parts of the Calvert family's rule in Maryland still exist today. Frederick County, Maryland, is named after the last Baron Baltimore. Other counties like Calvert, Cecil, Baltimore, Charles, Caroline, and Anne Arundel are also named after family members. The official flag of Maryland, unlike other states, still shows their family symbols.

After the Maryland State Convention of 1788, Maryland became the seventh state to approve the United States Constitution.

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |