Māori people facts for kids

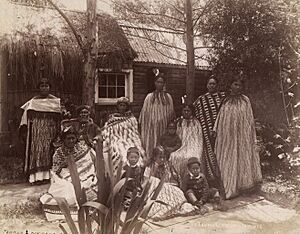

The Māori are the native Polynesian people of New Zealand. Their ancestors came from eastern Polynesia in large canoes, arriving in New Zealand sometime before the year 1300 CE. For many centuries, they lived in isolation and developed a unique culture. This culture included their own language, a rich collection of myths, special crafts, and performing arts. Early Māori lived in tribal groups, following Polynesian customs. They grew plants they brought with them, and over time, a strong warrior culture grew.

When Europeans started arriving in New Zealand in the 1600s, the Māori way of life changed a lot. Māori people slowly began to adopt parts of Western society and culture. At first, relations between Māori and Europeans were mostly friendly. After the Treaty of Waitangi was signed in 1840, both cultures lived together as part of a new British colony. However, disagreements over land sales led to conflicts in the 1860s. These conflicts, along with new diseases brought by Europeans, caused a huge drop in the Māori population.

By the early 1900s, the Māori population started to grow again. Efforts were made to improve their place in New Zealand society. Traditional Māori culture has seen a comeback, and a protest movement began in the 1960s to support Māori rights.

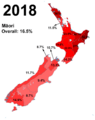

In the 2006 census, about 644,000 Māori lived in New Zealand, making up about 15% of the country's population. They are the second-largest ethnic group in New Zealand, after European New Zealanders (called "Pākehā"). More than 120,000 Māori also live in Australia. The Māori language (called te reo Māori) is spoken by about a quarter of all Māori and 4% of the total population. Many New Zealanders use Māori words like "kia ora" (hello) in everyday talk. Māori people are active in all parts of New Zealand culture and society, including media, politics, and sports.

Contents

What the Name "Māori" Means

In the Māori language, the word māori means "normal," "natural," or "ordinary." In old stories and traditions, the word was used to tell apart regular people (tāngata māori) from gods and spirits (wairua). Similarly, wai māori meant "fresh water" as opposed to salt water. Similar words exist in most Polynesian languages, all coming from an older word that meant "true, real, genuine."

How Māori People Name Themselves

Early European visitors to New Zealand often called the people "New Zealanders" or "natives." But Māori became the term Māori people used to describe themselves as a whole group.

Māori people often use the term tangata whenua (which means "people of the land"). This term shows their special connection to a certain area of land. A tribe might be the tangata whenua in one area but not in another. The term can also refer to all Māori people in relation to New Zealand (Aotearoa) as a whole country.

In 1947, a law called the Maori Purposes Act made it official to use "Maori" instead of "Native" in government documents. The Department of Native Affairs became the Department of Māori Affairs, and is now called Te Puni Kōkiri, or the Ministry for Māori Development.

Before 1974, how much Māori ancestry a person had decided if they were legally "a Māori person." For example, it affected whether someone could vote in the general elections or in the special Māori seats. In 1974, the Māori Affairs Amendment Act changed this. It said that a person's cultural self-identification would define them as Māori. For things like scholarships or Waitangi Tribunal settlements, some proof of ancestry or cultural connection is usually needed, but there's no minimum "blood" requirement.

History of the Māori People

Where Māori Came From

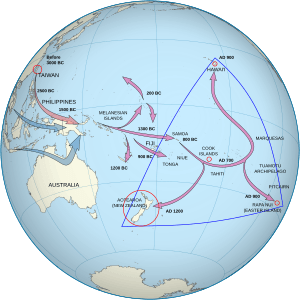

The best evidence we have suggests that people first settled in New Zealand around 1280 CE. Māori oral history tells of ancestors arriving from Hawaiki, a mythical homeland in tropical Polynesia. They came in large ocean-going canoes called waka. Different tribes (iwi) have their own stories about which waka their ancestors arrived on. There is little evidence of them returning to their original homelands.

There is no strong evidence that people lived in New Zealand before these Polynesian voyagers. Evidence from archaeology, language studies, and human remains shows that the first settlers came from eastern Polynesia and became the Māori. Studies of language and DNA suggest that most Pacific populations came from Taiwanese aborigines about 5,200 years ago, moving through Southeast Asia and Indonesia.

Early Māori Life (1280-1500)

The earliest time of Māori settlement is called the "Archaic" or "Moahunter" period. The Polynesian ancestors of the Māori arrived in a land covered in forests with many birds. These included several types of moa, which were large birds that are now extinct. Other extinct birds included a swan, a goose, and the huge Haast's eagle, which hunted the moa. Many seals lived along the coasts, much further north than they do today.

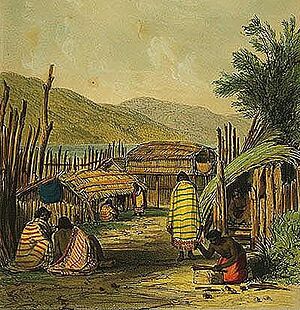

Archaeology shows that the Otago Region was a key place for Māori culture to develop during this time. Most early settlements were on or near the coast. These settlements ranged in size from about 40 people to 300–400 people. The most famous early site is Wairau Bar in the South Island, which was used from about 1288 to 1300.

During this early period, there were few weapons or forts, which were common later on. About 32 bird species became extinct, likely due to hunting by humans and the rats and dogs they brought, repeated burning of grasslands, or a cooler climate that started around 1400–1450. Early Māori ate a rich diet of birds, fish, seals, and shellfish. Moa were also an important food source and were likely hunted to extinction within 100 years.

Māori used about 36 different food plants, though many needed special preparation to remove toxins or long cooking times. Studies on early Māori fertility found that women had their first child around age 20, and the number of births was low. This might be because the average life expectancy was only about 31–32 years. Skeletons from Wairau Bar showed signs of a hard life, with many healed broken bones, suggesting a good diet and a community that helped injured members.

Classic Māori Period (1500-1642)

A sudden and long-lasting cooler climate period began around 1500. This happened at the same time as large earthquakes and tsunamis that destroyed many coastal settlements. The moa and other food species also became extinct. These changes likely led to big shifts in Māori culture, creating the "Classic" period that Europeans first saw.

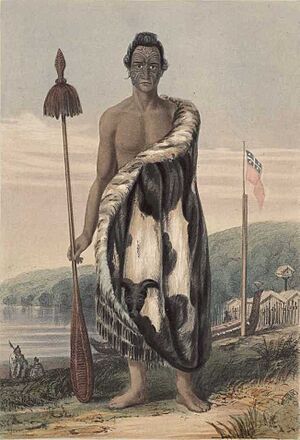

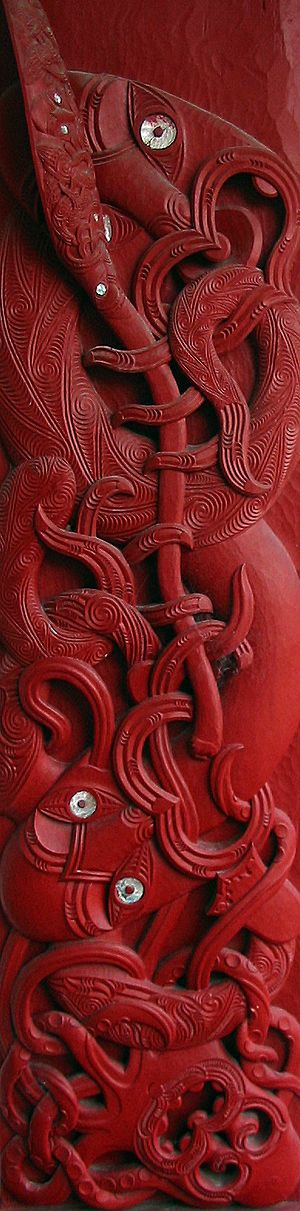

This period is known for beautiful pounamu (greenstone) weapons and ornaments. Canoes were carved with great detail, a tradition that later extended to meeting houses (wharenui). A fierce warrior culture developed, with strong forts called pā built on hills. Some of the largest war canoes ever made were built during this time.

Around 1500 CE, a group of Māori moved east to the Chatham Islands. There, they adapted to the local climate and resources, developing a culture called the "Moriori." This culture was related to Māori but had a strong focus on pacifism (peace). This proved to be a problem when a group of invading Taranaki Māori arrived in 1835. Few of the estimated 2,000 Moriori survived.

The biggest battle ever fought in New Zealand, the Battle of Hingakaka, happened around 1780–90. It was fought between about 7,000 warriors from a Taranaki-led group and a smaller Waikato group.

Early European Contact (1642-1840)

Europeans arrived in New Zealand quite recently in history. Historian Michael King described the Māori as "the last major human community on earth untouched and unaffected by the wider world." Early European explorers, like Abel Tasman (1642) and Captain James Cook (1769), wrote about their experiences with Māori. Initial meetings between Māori and Europeans were sometimes difficult and even deadly.

From the 1780s, Māori met European and American sealers and whalers. Some Māori even worked on these foreign ships. A few escaped convicts from Australia and sailors who left their ships also came to New Zealand. Early Christian missionaries also introduced new ideas. In the Boyd Massacre in 1809, Māori took and killed 66 crew members and passengers. This was likely revenge for the captain whipping the son of a Māori chief. This event made shipping companies and missionaries careful, reducing contact for several years.

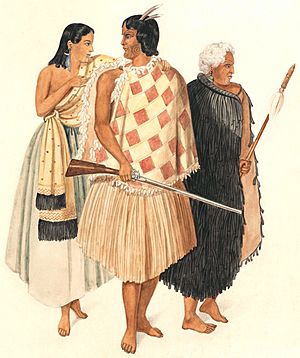

By 1830, about 2,000 Europeans lived among the Māori. These newcomers had different roles in Māori society, from slaves to important advisors. Some were like prisoners, while others left European culture and became Māori. These Europeans were called Pākehā Māori. Many Māori valued them for bringing European knowledge and technology, especially firearms. When Pomare led a war-party in 1838, he had 131 Europeans fighting with him.

From 1805 to 1840, Māori tribes who had close contact with Europeans got muskets. This changed the balance of power among Māori tribes, leading to a period of bloody inter-tribal fighting called the Musket Wars. These wars caused many tribes to be greatly reduced in number or driven from their lands.

European diseases like influenza and measles killed many Māori. Estimates suggest between ten and fifty percent of the population died. An epidemic called rewharewha by Māori "decimated" populations in the early 1800s. Other diseases like typhoid and whooping cough also took a heavy toll. Economic changes also caused problems. Moving to unhealthy swamp areas to grow and export flax led to more deaths.

British Rule in New Zealand

With more Christian missionaries and European settlers arriving in the 1830s, and concerns about lawlessness, the British Crown felt pressure to get involved. In January 1840, Queen Victoria officially took control of New Zealand.

In February 1840, William Hobson arrived and negotiated the Treaty of Waitangi with northern Māori chiefs (rangatira). Other rangatira later signed the treaty. In total, 500 rangatira out of 1500 sub-tribes signed it. Some important rangatira, like Pōtatau Te Wherowhero in Waikato, refused to sign. The Treaty gave Māori the rights of British citizens and promised to protect Māori property and tribal independence. In return, Māori accepted British government or sovereignty.

There is still debate about whether the Treaty of Waitangi truly gave away Māori sovereignty. Most rangatira signed a Māori version of the Treaty that did not fully match the English version. It seems unlikely that the Māori version gave away sovereignty. The British Crown and missionaries probably did not fully explain the meaning of the English version.

Despite these different understandings, relations between Māori and Europeans were mostly peaceful in the early colonial period. Many Māori groups started successful businesses, selling food and other products. George Grey, Governor of New Zealand from 1845–1855 and 1861–1868, learned the Māori language and wrote down many Māori myths.

However, growing tensions over land sales and attempts by Māori in the Waikato to create their own system of royalty led to the New Zealand wars in the 1860s. These conflicts were fought between British troops (helped by settlers and some allied Māori called kupapa) and Māori groups who opposed the land sales.

Even though relatively few Māori or Europeans died, the government took large areas of tribal land as punishment for what they called rebellion. In some cases, land was taken from tribes who had not even been involved in the war. Some of the taken land was given back, but other land was used for colonial expansion. Smaller conflicts also happened after the wars.

The Native Land Acts of 1862 and 1865 created the Native Land Court. Its goal was to change Māori land from being owned by the community to being owned by individuals. This made Māori land available to be sold to the government or to settlers. Between 1840 and 1890, Māori lost 95% of their land. Only 4% of this was confiscated, and about a quarter of that was returned. While individual Māori landowners received money from these sales, disputes later arose about whether promised payments were fully made. The selling of their land and a lack of new skills made it hard for Māori to join the growing New Zealand economy. This eventually weakened many iwi (tribes) and hapū (subtribes) from supporting themselves.

Decline and Revival

By the late 1800s, many Pākehā and Māori believed that the Māori population would disappear as a separate group and become part of the European population. In 1840, New Zealand had about 100,000 Māori and only about 2,000 Europeans. By 1860, the Māori population was estimated at 50,000. It dropped to 37,520 in the 1871 census. By 1896, the number was 42,113, while Europeans numbered over 700,000.

However, the Māori population did not continue to decline; it recovered. By 1936, the Māori population was 82,326. Despite many Māori and Europeans marrying each other, many Māori kept their cultural identity. Different ideas developed about what "Māori" meant and who counted as Māori.

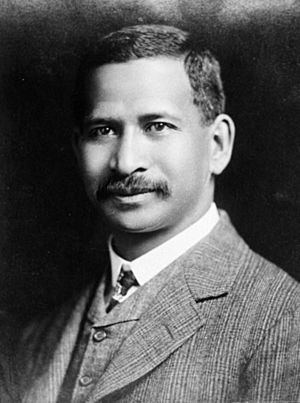

From the late 1800s, successful Māori politicians like James Carroll, Āpirana Ngata, Te Rangi Hīroa, and Maui Pomare showed great skill in Pākehā politics. At one point, Carroll even became Acting Prime Minister. This group, known as the Young Māori Party, aimed to bring new life to the Māori people after the hard times of the previous century. For them, this meant Māori adopting European ways of life like Western medicine and education. However, Ngata especially wanted to keep traditional Māori culture alive, particularly the arts. Ngata was a major force behind the revival of arts like kapa haka and carving. He also started a land development program that helped many iwi keep and develop their land.

The government decided not to make Māori join the army during World War II, but many Māori volunteered. They formed the 28th or Māori Battalion, which fought bravely in places like Crete, North Africa, and Italy. In total, 17,000 Māori took part in the war.

Many Māori moved to larger towns and cities during the Great Depression and after World War II to find jobs. This left rural communities with fewer people and disconnected many urban Māori from their traditional ways of life. While living standards improved for Māori during this time, they still lagged behind Pākehā in areas like health, income, skilled jobs, and higher education. Māori leaders and government officials struggled to deal with social problems from increased urban migration, such as not enough housing or jobs, and a rise in urban crime, poverty, and health issues.

Recent History

Since the 1960s, Māori culture has seen a revival, along with a protest movement. The government has recognized the growing political power of Māori and their activism. This has led to some solutions for the taking of land and other property rights violations. The Crown set up the Waitangi Tribunal, a group that investigates these issues and makes recommendations. However, it cannot make binding decisions, and the government does not have to accept its findings.

During the 1990s and 2000s, the government negotiated with Māori to provide solutions for the Crown's breaking of the Treaty of Waitangi promises from 1840. By 2006, the government had provided over NZ$900 million in settlements, much of it in land deals. The largest settlement, signed in 2008, gave nine large areas of forested land to Māori control. Because of these settlements, many iwi now have significant interests in the fishing and forestry industries. There is a growing group of Māori leaders who see these treaty settlements as a way to build economic development.

Even with growing acceptance of Māori culture in New Zealand, the settlements have caused some debate. Some Māori have complained that the settlements are too small compared to the value of the confiscated lands. On the other hand, some non-Māori say that the settlements and social programs are unfair special treatment based on race. Both of these feelings were seen during the New Zealand foreshore and seabed controversy in 2004.

Māori Culture

Traditional Māori Culture

The ancestors of the Māori arrived from eastern Polynesia in the 1200s, bringing their cultural customs and beliefs. Early European researchers sometimes misunderstood archaeological findings. However, the archaeological record shows a slow development of a culture that changed depending on local resources. Over a few centuries, the growing population led to competition for resources and more fighting. The archaeological record shows more fortified pā (forts), though there is still debate about how much conflict there was. Systems were created to save resources. Most of these, like tapu (sacred) and rāhui (restrictions), used religious threats to stop people from taking species at certain times or from specific areas.

Fighting between tribes was common, usually over land or to restore mana (prestige). Battles were fought between subtribes (hapū). Although not done during peaceful times, Māori would sometimes eat their defeated enemies. As Māori lived in isolation, performing arts like the haka developed from their Polynesian roots, as did carving and weaving. Regional dialects of the language appeared, with small differences in words and pronunciation. The language is still very similar to other Eastern Polynesian languages. A Tahitian chief on James Cook's first voyage could even act as an interpreter between Māori and Cook's crew.

Beliefs and Religion

Traditional Māori beliefs came from Polynesian culture. Many stories in Māori mythology are similar to stories found across the Pacific Ocean. Polynesian ideas like tapu (sacred), noa (non-sacred), mana (authority/prestige), and wairua (spirit) guided daily Māori life. These practices continued until Europeans arrived, when much of Māori religion was replaced by Christianity. Today, Māori often follow Presbyterianism, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Mormons), or Māori Christian groups like Rātana and Ringatū. There are also Catholic, Anglican, and Methodist groups, and a very small community of Māori Muslims.

Performing Arts

Kapa haka (meaning "haka team") is a traditional Māori performance art that is still popular today. It includes haka (a posture dance), poi (a dance with singing and rhythmic movements of a light ball on a string), waiata-ā-ringa (action songs), and waiata koroua (traditional chants). From the early 1900s, kapa haka groups began to tour overseas.

Since 1972, there has been a regular competition called the Te Matatini National Festival. Māori from different regions send groups to compete every two years. There are also kapa haka groups in schools, colleges, and workplaces. It is also performed at tourist places across the country.

Stories and Media

Before Europeans arrived, Māori did not have a written language. They kept their stories and beliefs alive through oral folklore, passing them down through generations. European missionaries taught Māori how to read and write. From the 1800s, Māori began to write down these histories in books and novels, and later on television. The use of the Māori language started to decline in the 1900s, and English became the language for much Māori literature.

Important Māori novelists include Patricia Grace, Witi Ihimaera, and Alan Duff. Once Were Warriors, a 1994 film based on Alan Duff's 1990 novel, showed the struggles of some urban Māori to a wide audience. It was the highest-grossing film in New Zealand until 2006 and won several international film awards. While some Māori worried that viewers might think the violent male characters were an accurate picture of Māori men, most critics praised it for showing the harsh reality of domestic violence. Some Māori, especially feminists, welcomed the discussion about domestic violence that the film started.

Māori actors and actresses are in many Hollywood movies because they can play characters who look like they are from Asia, Latin America, or the Middle East. They have been in films like Whale Rider, Star Wars, Revenge of the Sith, The Matrix, King Kong, The River Queen, The Lord of the Rings, and others. They have also been in famous TV series like Xena, Hercules: The Legendary Journeys, and Spartacus Blood and Sand. Famous Māori actors include Temuera Morrison, Cliff Curtis, Lawrence Makoare, Manu Bennett, and Keisha Castle-Hughes.

Sports

Māori fully take part in New Zealand's sports culture. The national rugby union, rugby league, and netball teams have had many Māori players. There are also Māori rugby union, rugby league, and cricket teams that play in international competitions. Ki-o-rahi and tapawai are two sports that came from Māori culture. Ki-o-rahi got a boost when McDonald's chose it to represent New Zealand. Waka ama (outrigger canoeing) is also popular with Māori.

Māori Language

The Māori language, also known as te reo Māori or simply te reo ("the language"), is an official language in New Zealand. Experts say it is closely related to Cook Islands Māori, Tuamotuan, and Tahitian. It is less closely related to Hawaiian and Marquesan, and more distantly to languages like Samoan and Tongan. Before Europeans arrived, Māori did not have a written language. Important information like whakapapa (genealogy) was memorized and passed down verbally through generations.

In many parts of New Zealand, Māori stopped being a common community language after World War II. But since the 1970s, along with calls for Māori rights, many New Zealand schools now teach Māori culture and language. Pre-school kohanga reo ("language-nests") have started, where young children (tamariki) are taught only in Māori. These programs now continue through secondary schools (kura tuarua).

In 2004, Māori Television, a government-funded channel that mainly broadcasts in te reo, began. Māori is an official language by law, but English is the main language used in the country. In the 2006 Census, Māori was the second most spoken language after English. Four percent of New Zealanders could speak Māori at least well enough for conversation.

Māori Society

How Māori Society Developed

Polynesian settlers in New Zealand developed a unique society over several hundred years. Social groups were tribal, and there was no single Māori identity until Europeans arrived. However, all Māori groups in pre-European New Zealand shared common things. These included a shared Polynesian background, a basic common language, family connections, traditions of warfare, and similar myths and religious beliefs.

Most Māori lived in villages. These villages were home to several whānau (extended families) who together formed a hapū (clan or subtribe). Members of a hapū worked together to produce food, gather resources, raise families, and defend themselves. Māori society across New Zealand generally had three classes: rangatira (chiefs and ruling families), tūtūā (commoners), and mōkai (slaves). Tohunga also held special respect in their communities as experts in important arts, skills, and knowledge.

Shared ancestry, intermarriage, and trade strengthened relationships between different groups. Many hapū with shared ancestry formed iwi, or tribes. These were the largest social units in Māori society. Hapū and iwi often joined together for food-gathering trips or during conflicts. On the other hand, warfare became a key part of traditional life as different groups competed for food and resources, settled personal arguments, and tried to increase their prestige and authority.

Europeans started arriving in New Zealand in the 1600s, but it was not until James Cook's trips over a hundred years later that significant interactions happened. For Māori, the new arrivals brought chances for trade, which many groups eagerly accepted. Early European settlers introduced tools, weapons, clothing, and foods to Māori across New Zealand. In return, they received resources, land, and labor. Māori began to choose parts of Western society to adopt during the 1800s, including European clothing and food, and later Western education, religion, and architecture.

But as the 1800s went on, relations between European settlers and different Māori groups became more difficult. Tensions led to conflicts in the 1860s, and the confiscation of millions of acres of Māori land. Large amounts of land were also bought by the government and later through the Native Land Court. The widespread selling of land and a lack of experience in managing money, along with low population growth and social disruption, greatly reduced the ability of many hapū and iwi to support themselves and maintain their social structure. The 1800s also saw a huge drop in the Māori population across New Zealand, mostly due to outbreaks of new diseases and worse living conditions.

1900s Changes

By the early 1900s, Māori had a stronger sense of being a single group, especially compared to Pākehā, who now greatly outnumbered them. Māori and Pākehā societies remained mostly separate – socially, culturally, economically, and geographically – for much of the 1800s and early 1900s. A key reason was that Māori mostly lived in rural areas, while Europeans increasingly lived in cities after 1900. Still, Māori groups continued to work with the government and use legal processes to improve their standing in New Zealand society. The main way they connected with the government was through the four Māori Members of Parliament.

Many Māori moved to larger rural towns and cities during the Great Depression and after World War II to find jobs. This left rural communities with fewer people and disconnected many urban Māori from their traditional social controls and tribal homelands. While living standards improved for Māori, they still lagged behind Pākehā in areas like health, income, skilled jobs, and higher education. Māori leaders and government officials struggled to deal with social issues from increased urban migration, such as not enough housing or jobs, and a rise in urban crime, poverty, and health problems.

A 1961 census showed big differences in living conditions between Māori and Europeans. For example, 96.8% of non-Māori homes had a bath or shower, compared to 76.8% of Māori homes. Similarly, 88.7% of non-Māori homes had a flush toilet, compared to 54.1% of Māori homes.

While the arrival of Europeans greatly changed the Māori way of life, many parts of traditional society have continued into the 2000s. Māori fully participate in all parts of New Zealand culture and society. They mostly live Western lifestyles while also keeping their own cultural and social customs. The old social classes of rangatira, tūtūā, and mōkai have mostly disappeared from Māori society. However, the roles of tohunga (experts) and kaumātua (elders) are still present. Traditional family ties are also actively kept up, and the whānau (extended family) remains a very important part of Māori life.

Marae, Hapū, and Iwi

Māori society at a local level is especially seen at the marae. In the past, these were the main meeting places in traditional villages. Today, marae usually have a group of buildings around an open space. They often host events like weddings, funerals, church services, and other large gatherings, usually following traditional rules and customs. They also serve as the base for one or more hapū (subtribes).

Most Māori belong to one or more iwi (tribes) and hapū, based on their family history (whakapapa). Iwi vary in size, from a few hundred members to over 100,000, like Ngāpuhi. Many people do not live in their traditional tribal regions anymore due to moving to cities.

Iwi are usually led by rūnanga – governing councils or trust boards. These groups represent the iwi in discussions and negotiations with the New Zealand government. Rūnanga also manage tribal assets and lead health, education, economic, and social programs to help iwi members.

Māori Population

In the 2006 Census, 565,000 people said they were part of the Māori ethnic group, which was 14.6% of the New Zealand population. However, 644,000 people (17.7%) said they had Māori ancestry. As of December 1, 2011, the estimated Māori population in New Zealand was 672,400. Many Māori also have some Pākehā ancestry because of a high rate of intermarriage between the two cultures.

According to the 2006 Census, the largest iwi by population is Ngāpuhi (122,000), followed by Ngāti Porou (72,000), Ngāti Kahungunu (60,000), and Ngāi Tahu (49,000). However, 102,000 Māori in the 2006 Census could not identify their iwi. Outside of New Zealand, a large Māori population lives in Australia, estimated at 126,000 in 2006. Smaller communities also exist in the United Kingdom (about 8,000), the United States (up to 3,500), and Canada (about 1,000).

Challenges for Māori

Māori generally have fewer assets than the rest of the population. They also face higher risks of negative economic and social outcomes. Over 50% of Māori live in areas with the highest levels of poverty, compared to 24% of the rest of the population. Although Māori make up only 14% of the population, they make up almost 50% of the prison population.

Māori also have higher unemployment rates than other groups living in New Zealand. Only 47% of Māori students finish school with qualifications higher than NCEA Level One. This compares to 74% for Europeans and 87% for Asians.

Race Relations

The special status of Māori as the native people of New Zealand is recognized in New Zealand law by the term tangata whenua (meaning "people of the land"). This term shows the traditional connection between Māori and a specific area of land. All Māori can be seen as tangata whenua of New Zealand. Individual iwi are recognized as tangata whenua for areas where they traditionally lived, and hapū are tangata whenua within their marae. New Zealand law sometimes requires the government to talk with tangata whenua. For example, during large land development projects. This usually means negotiations between local or national government and the rūnanga (councils) of one or more relevant iwi.

Māori issues are a big part of race relations in New Zealand. In the past, many Pākehā thought race relations in their country were the "best in the world." This view was common until Māori moved to cities in the mid-1900s, which brought cultural and socioeconomic differences to wider attention.

Māori protest movements grew a lot in the 1960s and 1970s. They sought solutions for past problems, especially regarding land rights. Governments have responded by creating programs to help Māori, funding cultural revival projects, and negotiating tribal settlements for past breaches of the Treaty of Waitangi. Further efforts have focused on preserving culture and reducing differences in wealth and social standing.

However, race relations remain a debated topic in New Zealand society. Māori advocates continue to push for more solutions, saying their concerns are not being heard. On the other hand, critics say that the help given to Māori is unfair preferential treatment based on race. Both of these feelings were highlighted during the foreshore and seabed controversy in 2004. In this event, the New Zealand government claimed sole ownership of the foreshore and seabed, against the wishes of Māori groups who wanted customary title.

Māori Business

The New Zealand Law Commission has started a project to create a legal system for Māori who want to manage shared resources and responsibilities. This voluntary system suggests an alternative to existing companies, corporations, and trusts. It would allow tribes, hapū, and other groups to work with the legal system. The proposed law, called the "Waka Umanga (Māori Corporations) Act," would offer a model that can be adapted to fit the needs of individual iwi.

More business exposure has made the public more aware of Māori culture. But it has also led to several notable legal disputes. Between 1998 and 2006, Ngāti Toa tried to trademark the haka "Ka Mate" to stop businesses from using it without their permission. In 2001, Danish toy maker Lego faced legal action from several Māori tribal groups. This was because Lego trademarked Māori words used in naming its Bionicle product range.

Māori in Politics

Māori have been involved in New Zealand politics since the Declaration of the Independence of New Zealand, even before the Treaty of Waitangi was signed in 1840. Māori have had special seats in the New Zealand Parliament since 1868. Currently, these account for seven of the 122 seats in New Zealand's parliament. Voting for these seats was the first chance for many Māori to take part in New Zealand elections. However, the elected Māori representatives at first struggled to have much influence. Māori received the right to vote for everyone, just like other New Zealand citizens, in 1893.

Since Māori are traditionally a tribal people, no single organization officially speaks for all Māori nationwide. The Māori King Movement started in the 1860s as an attempt by several iwi to unite under one leader. Today, it mostly serves a ceremonial role. Another attempt at political unity was the Kotahitanga Movement. It set up a separate Māori Parliament that met every year from 1892 until 1902.

There are seven special Māori seats in the New Zealand Parliament. Māori can also run for and win general seats. Talking with and considering Māori views has become a regular requirement for councils and government organizations. There is often debate about how relevant and fair the Māori electoral roll is. The National Party announced in 2008 that it would get rid of these seats once all historical Treaty settlements are completed, which they aimed to do by 2014. Several Māori political parties have formed over the years to improve the position of Māori in New Zealand society. The current Māori Party, formed in 2004, won 1.43% of the party vote in the 2011 general election and holds three seats in the 50th New Zealand Parliament. Two of their Members of Parliament serve as Ministers outside the Cabinet.

- Māori has similar words in other Polynesian languages like Hawaiian 'Maoli,' Tahitian 'Mā'ohi,' and Cook Islands Maori 'Māori,' all with similar meanings.

- The Māori Language Commission suggests using the macron (ā ē ī ō ū) to show long vowels. In modern English in New Zealand, people usually avoid adding an "s" to make "Māori" plural. Māori usually show plurals by changing the article before the word, for example: te waka (the canoe); ngā waka (the canoes).

- In 2003, Christian Cullen became a member of the Māori rugby team even though his father said he had only about 1/64 Māori ancestry.

Images for kids

-

Early Archaic period objects from the Wairau Bar archaeological site, on display at the Canterbury Museum in Christchurch

-

Depiction of the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi in 1840, bringing New Zealand and the Māori into the British Empire

-

Members of the 28th (Māori) Battalion performing a haka, Egypt (July 1941)

-

Wharenui (meeting house) at Ōhinemutu village, Rotorua (tekoteko on the top)

-

Māori woman with a representation of the Waikato Ancestress "Te Iringa"

-

A haka performed by the national rugby union team before a game

See also

In Spanish: Maorí para niños

In Spanish: Maorí para niños

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |