Gioachino Rossini facts for kids

Gioachino Antonio Rossini (born February 29, 1792 – died November 13, 1868) was a famous Italian composer. He became well-known for his 39 operas. An opera is a play where the story is told mostly through singing, with music played by an orchestra. Rossini also wrote many songs, some chamber music (music for a small group of instruments), piano pieces, and sacred music (music for religious services). He set new standards for both funny (comic) and serious operas. He stopped writing large operas when he was in his thirties, even though he was very popular.

Rossini was born in Pesaro, Italy. Both his parents were musicians; his father played the trumpet, and his mother was a singer. Rossini started composing music by age 12 and studied at a music school in Bologna. His first opera was performed in Venice in 1810 when he was 18. From 1810 to 1823, he wrote 34 operas for Italian stages in cities like Venice, Milan, and Naples. During this time, he created his most popular works. These include the funny operas L'italiana in Algeri, Il barbiere di Siviglia (known as The Barber of Seville), and La Cenerentola (the Cinderella story). These operas perfected the opera buffa (comic opera) style. He also wrote serious operas like Otello, Tancredi, and Semiramide. People admired his music for its new melodies, interesting sounds, and dramatic forms. In 1824, he moved to Paris to work for the Opéra. There, he wrote Il viaggio a Reims for a king's celebration and revised two of his Italian operas. In 1829, he wrote his last opera, Guillaume Tell.

Rossini stopped writing operas for the last 40 years of his life. No one knows exactly why, but it might have been because of his health, the money he had earned, or the rise of new opera styles. From the 1830s to 1855, he wrote very little music. When he returned to Paris in 1855, he became famous for his Saturday music parties, called "salons." Many famous musicians and artists attended these parties. For these gatherings, he wrote fun pieces called Péchés de vieillesse (Sins of Old Age). His last major work was his Petite messe solennelle (Little Solemn Mass) in 1863. He passed away in Paris in 1868.

Life and Career

Early Years

Gioachino Rossini was born in 1792 in Pesaro, a town on the Adriatic coast of Italy. He was the only child of Giuseppe Rossini, who played the trumpet and horn, and Anna, a seamstress and singer. His father was a bit wild, so his mother mostly supported the family and raised Gioachino.

In 1798, when Rossini was six, his mother started a successful career as a professional singer in comic operas. She performed in cities like Trieste and Bologna. In 1802, the family moved to Lugo. There, Rossini got a good basic education in Italian, Latin, and math, as well as music. He learned the horn from his father and studied other music with a priest, Giuseppe Malerbe. This priest had a large library with music by Haydn and Mozart, who were not well-known in Italy then. These composers greatly inspired young Rossini.

He learned quickly. By age twelve, he had written six sonatas for four stringed instruments. These were performed in 1804. Two years later, he joined the Liceo Musicale in Bologna. He first studied singing, cello, and piano, then joined the composition class. He wrote important pieces as a student, including a mass. After two years, he was asked to continue his studies, but he said no. He felt he had learned enough and wanted to gain experience in the real world of music.

While at the Liceo, Rossini sang in public and worked in theaters. He was a répétiteur (someone who helps singers learn their parts) and a keyboard player. In 1810, a famous singer named Domenico Mombelli asked him to write his first opera, Demetrio e Polibio. It was performed in 1812, after Rossini had already found success with other works. Rossini and his parents decided that his future was in writing operas. The main opera center in northern Italy was Venice. Rossini moved there in late 1810, at age eighteen, with help from a family friend, the composer Giovanni Morandi.

Early Operas: 1810–1815

Rossini's first opera to be performed was La cambiale di matrimonio, a short comedy. It opened at the small Teatro San Moisè in November 1810. The opera was a big hit, and Rossini earned a good amount of money. He later said the San Moisè was perfect for a young composer. It had no chorus and a small group of main singers. Its main shows were short comic operas, performed with simple sets and little rehearsal. After this success, Rossini wrote three more short comedies for the theater: L'inganno felice (1812), La scala di seta (1812), and Il signor Bruschino (1813).

Rossini also worked in Bologna, where he successfully directed Haydn's The Seasons in 1811. He also worked for opera houses in Ferrara and Rome. In mid-1812, he got a job from La Scala, a famous opera house in Milan. His two-act comedy La pietra del paragone was performed 53 times, which was a lot for that time. This success brought him money and freed him from military service. It also gave him the title of maestro di cartello, meaning his name on posters guaranteed a full house.

The next year, his first serious opera, Tancredi, did well in Venice and even better in Ferrara, with a new, sad ending. The success of Tancredi made Rossini famous around the world. Productions of the opera were staged in London (1820) and New York (1825). Just weeks after Tancredi, Rossini had another hit with his comedy L'italiana in Algeri, which he wrote very quickly and premiered in May 1813.

The year 1814 was less successful for Rossini. His operas Il turco in Italia and Sigismondo did not please audiences in Milan or Venice. But 1815 was an important year for his career. In May, he moved to Naples to become the music director for the royal theaters. These included the Teatro di San Carlo, the city's main opera house. Its manager, Domenico Barbaia, was very important for Rossini's career there.

Naples and The Barber of Seville: 1815–1820

At first, the musicians in Naples were not happy about Rossini, seeing him as an outsider. Naples had been a major opera city, and composers like Cimarosa and Paisiello were highly respected. But Rossini quickly won over the public and critics. His first work for the San Carlo, Elisabetta, regina d'Inghilterra, was a serious opera. In it, he reused parts of his older works, which were new to the Naples audience. This opera was a huge success, as was the Naples premiere of L'italiana in Algeri. Rossini's place in Naples was secure.

For the first time, Rossini could write regularly for a group of top singers and a great orchestra. He had enough rehearsal time and didn't have to rush. Between 1815 and 1822, he wrote eighteen more operas: nine for Naples and nine for other cities. In 1816, for the Teatro Argentina in Rome, he composed the opera that would become his most famous: Il barbiere di Siviglia (The Barber of Seville). There was already a popular opera with that title by Paisiello. Rossini's version was first called Almaviva, after its hero. Despite a difficult opening night with stage problems and many people supporting Paisiello, the opera quickly became a hit. A few months later, it was called by its current Italian title and soon became more popular than Paisiello's version.

Rossini's operas for the Teatro San Carlo were mostly serious and important works. His Otello (1816) was very popular and was performed often. Other works for the San Carlo included Mosè in Egitto, based on the biblical story of Moses and the Exodus from Egypt (1818), and La donna del lago, based on Sir Walter Scott's poem The Lady of the Lake (1819). For La Scala, he wrote the semi-serious opera La gazza ladra (1817). For Rome, he wrote his version of the Cinderella story, La Cenerentola (1817). In 1817, one of his operas, L'Italiana, was performed for the first time in Paris. Its success led to more of his operas being staged there, and eventually to his contract in Paris from 1824 to 1830.

Rossini liked to keep his private life secret, but he was known to be interested in the singers he worked with. The most important relationship was with Isabella Colbran, the main singer at the Teatro San Carlo. Rossini had heard her sing in Bologna in 1807. When he moved to Naples, he wrote many important roles for her in his serious operas.

Vienna and London: 1820–1824

By the early 1820s, Rossini was getting tired of Naples. His serious opera Ermione had failed the year before, and he felt he and the Naples audiences had had enough of each other. A rebellion in Naples against the king, though quickly stopped, made Rossini uneasy. When Barbaia signed a contract to take the opera company to Vienna, Rossini was happy to go. He traveled with Colbran in March 1822. They stopped in Bologna, where they got married in a small church near the city. She was 37, and he was 30.

In Vienna, Rossini was welcomed like a hero. People were incredibly excited, calling it "Rossini fever." The leader of the Austrian Empire, Metternich, liked Rossini's music and thought it was safe from any revolutionary ideas. So, he allowed the San Carlo company to perform six of Rossini's operas during a three-month season.

While in Vienna, Rossini heard Beethoven's Eroica symphony. He was so moved that he decided to meet the reclusive composer. He finally did, and later told many people about the meeting. He remembered that even though it was hard to talk because Beethoven was deaf and Rossini didn't speak German, Beethoven made it clear that he thought Rossini's talent was not for serious opera. Beethoven told him he should "do more Barbiere" (more *Barbers*).

After the Vienna season, Rossini went back to Castenaso to work on Semiramide with his writer, Gaetano Rossi. This opera was for La Fenice in Venice. It premiered in February 1823 and was his last work for the Italian theater. Colbran was the star, but it was clear her voice was declining, and Semiramide ended her career in Italy. Despite this, the opera became popular worldwide and remained so throughout the 1800s. It brought Rossini's "Italian career to a spectacular close."

In November 1823, Rossini and Colbran went to London for a good contract. They stopped for four weeks in Paris. Parisians were very welcoming, though not as wildly excited as the Viennese. When he attended a performance of Il barbiere, he was cheered, brought onto the stage, and serenaded by the musicians. A big dinner was held for him and his wife, attended by leading French composers and artists. He found the cultural scene in Paris very enjoyable.

At the end of the year, Rossini arrived in London. He was welcomed by King George IV, though Rossini was not easily impressed by royalty anymore. Rossini and Colbran had signed contracts for an opera season at the King's Theatre. Her voice problems were a big issue, and she sadly stopped performing. The public was also unhappy because Rossini did not provide a new opera as promised. The theater manager failed to keep his contract with Rossini, but the public blamed Rossini.

A writer named Gaia Servadio said in 2003 that Rossini and England were not a good match. He felt sick after crossing the English Channel, and he probably didn't like the English weather or food. Even though his time in London earned him a lot of money (over £30,000, which the British press complained about), he was happy to sign a contract to return to Paris, where he felt much more at home.

Paris and Final Operas: 1824–1829

Rossini's new, well-paying contract with the French government was made under King Louis XVIII, who died in September 1824, soon after Rossini arrived in Paris. The agreement was that Rossini would write one grand opera for the Académie Royale de Musique and one comic or semi-serious opera for the Théâtre-Italien. He was also to help manage the latter theater and update one of his older works. The king's death and the new king, Charles X, changed Rossini's plans. His first new work for Paris was Il viaggio a Reims, an opera written in June 1825 to celebrate Charles's coronation. This was his last opera with an Italian story. He allowed only four performances, planning to use the best music in a more lasting opera. About half of the music for Le comte Ory (1828) came from this earlier work.

Colbran's forced retirement put a strain on the Rossinis' marriage. She had nothing to do, while he was still the center of musical attention. She found comfort in shopping. For Rossini, Paris offered endless delicious food, which showed in his growing size.

The first two operas Rossini wrote with French stories were Le siège de Corinthe (1826) and Moïse et Pharaon (1827). Both were major changes of operas he wrote for Naples: Maometto II and Mosè in Egitto. Rossini took great care before starting. He learned to speak French and understood how French opera traditionally used the language. He removed some of the old, fancy music that was out of style in Paris. He also added dances, hymn-like songs, and gave the chorus a bigger role to fit local tastes.

Rossini's mother, Anna, died in 1827. He loved her very much and felt her loss deeply. She and Colbran had never gotten along well. Some suggest that after Anna died, Rossini started to resent Colbran.

In 1828, Rossini wrote Le comte Ory, his only French comic opera. His decision to reuse music from Il viaggio a Reims caused problems for his writers. They had to change their original plot and write French words to fit existing Italian music. But the opera was a success. It was performed in London within six months and in New York in 1831. The next year, Rossini wrote his long-awaited French grand opera, Guillaume Tell. It was based on Friedrich Schiller's 1804 play about the William Tell legend.

Early Retirement: 1830–1855

Guillaume Tell was well-received. After the premiere, the orchestra and singers gathered outside Rossini's house and played the exciting ending of the second act for him. The newspaper Le Globe said that a new era of music had begun. Gaetano Donizetti joked that the first and last acts were by Rossini, but the middle act was by God. The work was a clear success, though not an instant smash hit. It took time for the public to fully appreciate it, and some singers found it very challenging. Still, it was performed abroad within months, and no one thought it would be his last opera.

Guillaume Tell is Rossini's longest opera, lasting nearly four hours. Writing it left him very tired. Although he planned an opera about the Faust story within a year, other events and his poor health stopped him. After Guillaume Tell opened, the Rossinis left Paris and stayed in Castenaso. Within a year, events in Paris made Rossini hurry back. King Charles X was overthrown in a revolution in July 1830. The new government, led by Louis Philippe I, announced big cuts in spending. One of these cuts was Rossini's lifetime payment, which he had worked hard to get from the previous government. Trying to get this payment back was one reason Rossini returned. The other was to be with his new partner, Olympe Pélissier. He left Colbran in Castenaso; she never returned to Paris, and they never lived together again.

People have always wondered why Rossini stopped writing operas. Some thought that at 37, with some health issues, a good payment from the French government, and 39 operas written, he simply decided to retire. The poet Heine compared Rossini's retirement to Shakespeare's, saying both geniuses knew when they had done their best work. Others thought Rossini retired because he was upset by the success of other composers like Giacomo Meyerbeer. However, modern experts believe Rossini did not plan to stop writing operas. They think circumstances, especially his health, made Guillaume Tell his last. From about this time, Rossini had health problems, both physical and mental. He suffered from periods of deep sadness, which some link to a mood disorder or his mother's death.

For 25 years after Guillaume Tell, Rossini composed little. However, experts say his few works from the 1830s and 1840s still show great musical ideas. These include the Soirées musicales (1830–1835), a set of twelve songs for voices and piano, and his Stabat Mater (started in 1831, finished in 1841). After winning his fight with the government over his payment in 1835, Rossini left Paris and settled in Bologna. His return to Paris in 1843 for medical treatment made people hope he would write a new grand opera. There were rumors he was working on a story about Joan of Arc. The Opéra presented a French version of Otello in 1844, which included music from his earlier operas. It's unclear how much Rossini was involved, but the show was not well-received. More controversial was the opera Robert Bruce (1846). For this, Rossini, back in Bologna, helped choose music from his past operas that hadn't been performed in Paris, like La donna del lago. The Opéra tried to present Robert as a new Rossini opera. But critics said it was "fake goods" and from an old style.

After 1835, Rossini formally separated from his wife, Isabella, who stayed in Castenaso (1837). His father died in 1839 at age 80. In 1845, Colbran became very ill, and Rossini visited her a month before she died. The next year, Rossini and Pélissier got married in Bologna. The revolutions of 1848 made Rossini move away from Bologna, where he felt unsafe. He made Florence his home until 1855.

By the early 1850s, Rossini's health, both mental and physical, had gotten so bad that his wife and friends worried about him. By the middle of the decade, it was clear he needed to return to Paris for the best medical care. In April 1855, the Rossinis left Italy for France for the last time. Rossini returned to Paris at age 63 and lived there for the rest of his life.

"Sins of Old Age": 1855–1868

When Rossini returned to Paris, he got his health and joy for life back. He had two homes: a flat in a fancy central area and a villa in Passy, which was then a quiet, semi-rural town. He and his wife started a famous social gathering called a salon. Their first Saturday evening gathering, the samedi soirs, was in December 1858. The last was two months before he died in 1868.

Rossini started composing again. His music from his last ten years was not usually meant for public performance. He often didn't put dates on his music, so it's hard for music experts to know exactly when he wrote them. One of the first was a song cycle called Musique anodine, dedicated to his wife in April 1857. For his weekly salons, he wrote over 150 pieces. These included songs, piano solos, and chamber music for different instruments. He called them his Péchés de vieillesse – "sins of old age." The salons were held at his villa and, in winter, at his Paris flat. These gatherings were common in Paris, but the Rossinis' samedi soirs quickly became the most desired invitation in the city. Rossini carefully chose the music, playing his own works and pieces by composers like Pergolesi, Haydn, Mozart, and some of his guests.

Among the composers who attended and sometimes performed were Auber, Gounod, Liszt, Rubinstein, Meyerbeer, and Verdi. Rossini liked to call himself a "fourth-class pianist," but many famous pianists at the salons were amazed by his playing. Violinists like Pablo Sarasate and Joseph Joachim were regular guests. In 1860, Richard Wagner visited Rossini.

One of Rossini's few later works meant for public performance was his Petite messe solennelle (Little Solemn Mass), first performed in 1864. In the same year, Napoleon III made Rossini a grand officer of the Legion of Honour, a very important French award.

After a short illness and an unsuccessful operation for cancer, Rossini died in Passy on November 13, 1868, at age 76. He left his wife, Olympe, the right to use his estate during her lifetime. After her death ten years later, the money went to the city of Pesaro to start a music school and fund a home for retired opera singers in Paris. More than 4,000 people attended his funeral service at the church of Sainte-Trinité in Paris. Rossini's body was buried at the Père Lachaise Cemetery. In 1887, his remains were moved to the church of Santa Croce in Florence.

Music

Rossini's Musical Style

A writer named Julian Budden called Rossini's musical methods "the Code Rossini." This refers to the way Rossini used certain formulas for his overtures (the music played before an opera begins), arias (songs for one singer), and other parts. This allowed him to compose many operas quickly. Rossini's music was also influenced by French rule in Italy, which brought "new military qualities of attack, noise and speed." Rossini had to adapt his style to changing tastes and audience demands. Old-fashioned opera stories were replaced by more romantic ones, which needed stronger characters and faster action. Rossini's methods helped him meet these demands.

It was very important for Rossini to use a formulaic approach, especially early in his career. In seven years (1812–1819), he wrote 27 operas, often with very little time. For La Cenerentola (1817), for example, he had just over three weeks to write all the music before the first performance.

This pressure also led Rossini to reuse music. He often took a successful overture and used it in later operas. For example, the overture to La pietra del paragone was later used for the serious opera Tancredi (1813). The overture to Aureliano in Palmira (1813) is now best known as the overture to the comedy Il barbiere di Siviglia. He also freely reused songs and other musical parts in new works. One writer noted that out of 26 pieces in Eduardo e Cristina (1817), 19 were taken from earlier works. Rossini was annoyed when a publisher released a complete collection of his works in the 1850s. He said, "The same pieces will be found several times, for I thought I had the right to remove from my failures those pieces which seemed best, to rescue them from shipwreck."

Overtures

Philip Gossett, a music expert, says Rossini "was from the outset a consummate composer of overtures." His basic formula for these stayed the same throughout his career. They were like sonata movements (a common musical structure) but without a middle development section. They usually started with a slow introduction and had clear melodies, lively rhythms, and simple harmonies. They often built to a loud climax using a crescendo (gradually getting louder). Another expert, Richard Taruskin, points out that the second main tune in Rossini's overtures is always played by a woodwind instrument (like a flute or clarinet). This tune is so catchy that it sticks in your mind. Rossini's rich and creative use of the orchestra, even in his early works, helped start the "great nineteenth-century flowering of orchestration" (the art of arranging music for an orchestra).

Arias

Rossini's way of writing arias (songs for one singer) and duets (songs for two singers) in a style called cavatina was a new development. In the past, operas often stopped the action for long recitative (spoken-like singing) and aria sections. Rossini made the aria "an engine for releasing emotion." His typical aria structure had a lyrical, flowing introduction (the "cantabile") and a more intense, brilliant ending (the "cabaletta"). This structure could be changed to move the story forward. For example, other characters could make comments during the aria, or the chorus could sing between the cantabile and cabaletta to excite the soloist. While Rossini didn't invent all these ideas, he mastered them.

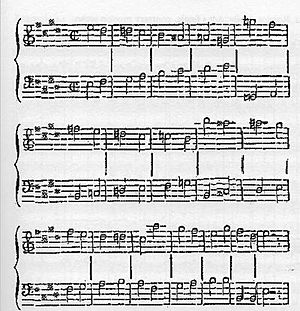

A very important example is the cavatina "Di tanti palpiti" from Tancredi. Experts call it "the most famous aria Rossini ever wrote." It has a melody that captures the beauty and innocence of Italian opera. Rossini often added a clever touch by avoiding an expected ending in the aria, suddenly changing keys. This musical shift happens as the words talk about returning, but the music goes in a new direction. Rossini's cabaletta style continued to influence Italian opera even as late as Giuseppe Verdi's Aida (1871).

Structure

Rossini's way of connecting the singing parts with the opera's story was a big change. In his works, solo arias became a smaller part of the operas. Instead, he used more duets (which also often followed the cantabile-caballetta format) and ensembles (songs for many singers).

In the late 1700s, composers of comic operas had started to make the finales (endings) of each act more dramatic. Finales grew longer, becoming a continuous chain of music with different speeds and styles, building to a loud and exciting final scene. In his comic operas, Rossini brought this technique to its peak. For example, the finale of the first act of L'italiana in Algeri is very concentrated and exciting.

Even more important for opera history was Rossini's ability to use this technique in serious operas. In his analysis of the first-act finale of Tancredi, Philip Gossett points out several elements Rossini used. These include contrasting "kinetic" action scenes (often with orchestral tunes) with "static" expressions of emotion. The final "static" part was a cabaletta, with all the characters joining in the final chords. Gossett says that from Tancredi onwards, the cabaletta became the required ending for each musical section in operas by Rossini and his peers.

Early Works

With very few exceptions, all of Rossini's compositions before his retirement involved singing. His very first surviving work (besides one song) is a set of string sonatas for two violins, cello, and double-bass. He wrote these at age 12, when he had just started learning composition. These pieces are tuneful and engaging. They show that the talented young Rossini was not yet influenced by the new musical forms developed by Mozart, Haydn, and Beethoven. Instead, his focus was on flowing melodies, musical color, variations, and impressive playing, rather than complex musical development. These qualities are also clear in Rossini's early operas, especially his farse (one-act farces), more than his serious operas.

Experts note that these early works were written when the styles of older composers like Cimarosa and Paisiello were no longer dominant. Rossini was stepping in to fill that gap. The Teatro San Moisè in Venice, where his farse were first performed, and the La Scala Theatre of Milan, which premiered his two-act opera La pietra del paragone (1812), were looking for works in that tradition. In these operas, "Rossini's musical personality began to take shape... many elements emerge that remain throughout his career," including "a love of pure sound, of sharp and effective rhythms." An example of his clever originality is the unusual effect in the overture of Il signor Bruschino (1813), where violin bows tap rhythms on music stands.

Italy, 1813–1823

The great success in Venice of both Tancredi and the comic opera L'italiana in Algeri within a few weeks of each other (February 6, 1813, and May 22, 1813) confirmed Rossini's reputation as the most promising opera composer of his time. From late 1813 to mid-1814, he was in Milan creating two new operas for La Scala, Aureliano in Palmira and Il Turco in Italia. The role of Arsace in Aureliano was sung by Giambattista Velluti. Some rumored that Rossini was unhappy with Velluti's ornamentation (extra musical decorations) of his music. However, throughout his Italian period, up to Semiramide (1823), Rossini's written vocal lines became more and more elaborate, which was part of his own changing style.

Rossini's work in Naples helped this style develop. The city, which was known for the operas of Cimarosa and Paisiello, had been slow to accept Rossini. But Domenico Barbaia invited him in 1815 for a seven-year contract to manage his theaters and compose operas. For the first time, Rossini could work for a long time with a group of musicians and singers. These included Isabella Colbran, Andrea Nozzari, and Giovanni David, who "all specialized in florid singing" (singing with many fast notes and decorations). Their talents had a big impact on Rossini's style. Rossini's first operas for Naples, Elisabetta, regina d'Inghilterra and La gazzetta, mostly reused parts from earlier works. But Otello (1816) is known not only for its impressive singing parts but also for its wonderfully put-together last act. The drama is highlighted by the melody, orchestration, and musical color. In the opinion of music expert Gossett, this is where "Rossini came of age as a dramatic artist."

By now, Rossini's career was gaining attention across Europe. Other composers came to Italy to study the revival of Italian opera. Among them was Giacomo Meyerbeer from Berlin, who arrived in Italy in 1816 and lived and worked there until he followed Rossini to Paris in 1825. Meyerbeer used one of Rossini's writers, Gaetano Rossi, for five of his seven Italian operas. In a letter from September 1818, Meyerbeer gave a detailed review of Otello. He criticized Rossini for reusing music in the first two acts. But he admitted that the third act "so firmly established Rossini's reputation in Venice that even a thousand follies could not rob him of it. But this act is divinely beautiful."

Rossini's contract did not stop him from taking other jobs. Before Otello, Il barbiere di Siviglia, a great example of the comic opera tradition, had premiered in Rome (February 1816).

Besides La Cenerentola (Rome, 1817) and the short comic opera Adina (1818, performed in 1826), Rossini's other works during his Naples contract were all serious operas. Among the most notable, all with challenging singing roles, were Mosè in Egitto (1818), La donna del lago (1819), Maometto II (1820) – all staged in Naples – and Semiramide, his last opera written for Italy, staged in Venice in 1823. The three versions of the semi-serious opera Matilde di Shabran were written in 1821/1822. Both Mosè and Maometto II were later greatly changed for Paris.

France, 1824–1829

As early as 1818, Meyerbeer heard rumors that Rossini was looking for a good job at the Paris Opéra. About six years later, this came true.

In 1824, Rossini, under a contract with the French government, became director of the Théâtre-Italien in Paris. There, he introduced Meyerbeer's opera Il crociato in Egitto. For his own work, he wrote Il viaggio a Reims to celebrate the crowning of Charles X (1825). This was his last opera with an Italian story. He later used parts of it to create his first French opera, Le comte Ory (1828). A new contract in 1826 meant he could focus on productions at the Opéra. For this, he greatly revised Maometto II as Le siège de Corinthe (1826) and Mosé as Moïse et Pharaon (1827). To fit French tastes, these works were made longer (each by one act). The singing parts were less elaborate, and the dramatic structure was improved, with fewer arias. One striking addition was the chorus at the end of Act III of Moïse. It had a crescendo (getting louder) repetition of a rising bass line, which greatly excited audiences.

Rossini's government contract required him to create at least one new "grand opera." Rossini chose the story of William Tell. He worked closely with the writer Étienne de Jouy. This story allowed him to explore his interest in folk music and picturesque scenes. This is clear from the overture, which describes weather, scenery, and action. It also includes a version of the ranz des vaches, the Swiss cowherd's call, which appears throughout the opera. This gives it a "leitmotif" (a recurring musical theme). According to music historian Benjamin Walton, Rossini filled the work with so much local flavor that there was little room for anything else. The roles for solo singers were much smaller compared to other Rossini operas. The hero didn't even have his own aria, while the chorus of the Swiss people was always important in the music and drama.

Guillaume Tell premiered in August 1829. Rossini also made a shorter, three-act version for the Opéra. It was first performed in 1831 and became the basis for future productions. Tell was very successful from the start and was often performed. In 1868, Rossini attended its 500th performance at the Opéra. The Globe newspaper enthusiastically reported that "a new epoch has opened not only for French opera, but for dramatic music elsewhere." This was an era, it turned out, in which Rossini would no longer actively participate.

Withdrawal, 1830–1868

Rossini's contract required him to provide five new works for the Opéra over 10 years. After Tell premiered, he considered other opera ideas, including Goethe's Faust. But the only major works he finished before leaving Paris in 1836 were the Stabat Mater, written for a private request in 1831 (finished and published in 1841), and the collection of salon songs Soirées musicales, published in 1835. Living in Bologna, he taught singing at the Liceo Musicale. He also created a pasticcio (an opera made from existing music) of Tell, called Rodolfo di Sterlinga. For this, Giuseppe Verdi wrote some new songs.

Because of continued demand in Paris, a "new" French version of Otello was produced in 1844 (Rossini was not involved). Also, a "new" opera Robert Bruce was created. For this, Rossini worked with Louis Niedermeyer and others to adapt music from La donna del lago and other works that were not well-known in Paris, to fit a new story. The success of both these operas was limited.

It wasn't until Rossini returned to Paris in 1855 that his musical spirit seemed to revive. He wrote many pieces for voices, choir, piano, and small groups of instruments for his evening parties. These pieces, called Péchés de vieillesse (Sins of Old Age), were published in thirteen volumes from 1857 to 1868. Volumes 4 to 8 contain "56 semi-comical piano pieces... dedicated to pianists of the fourth class, to which I have the honor of belonging." These include a playful funeral march, Marche et reminiscences pour mon dernier voyage (March and reminiscences for my last journey). Music expert Gossett says of the Péchés: "Their historical position remains to be assessed but it seems likely that their effect, direct or indirect, on composers like Camille Saint-Saëns and Erik Satie was significant."

The most important work of Rossini's last ten years was the Petite messe solennelle (Little Solemn Mass) (1863). It was written for a small group of performers (originally voices, two pianos, and a harmonium). Because of this, it wasn't suitable for large concert halls. Also, since it included women's voices, it wasn't allowed in churches at the time. For these reasons, this piece has been somewhat overlooked among Rossini's compositions. It is not especially "little" nor entirely "solemn," but it is known for its grace, counterpoint (combining melodies), and beautiful tunes.

Influence and Legacy

Rossini's popular melodies led many skilled musicians of his time to create piano versions or fantasies based on them. Examples include Sigismond Thalberg's fantasy on themes from Moïse, and variations on "Non più mesta" from La Cenerentola by composers like Frédéric Chopin and Franz Liszt. Liszt also transcribed the William Tell overture (1838) and the Soirées musicales.

Even though his comic operas remained popular, and Italian opera forms continued to be influenced by his new ideas, Rossini's place in music history became less clear. This was partly because the singing and staging styles of his time changed. Also, the idea of a composer as a "creative artist" rather than a craftsman became more common. Rossini's importance among his Italian composer friends is shown by the Messa per Rossini, a project started by Verdi just days after Rossini's death. Verdi and a dozen other composers worked together to create this mass.

Rossini's main legacy for Italian opera was in vocal forms and dramatic structure for serious opera. For French opera, he helped bridge the gap from comic opera to the development of opéra comique (and later to operetta). Comic operas influenced by Rossini's style include François-Adrien Boieldieu's La dame blanche (1825) and Daniel Auber's Fra Diavolo (1830). However, Hector Berlioz criticized Rossini's style, calling it "melodic cynicism" and complaining about his "endless repetition of a single form of cadence."

It was perhaps expected that Rossini's huge fame during his lifetime would fade later. In 1886, less than 20 years after his death, Bernard Shaw wrote that Rossini, whose Semiramide once seemed amazing, was no longer seen as a serious musician.

In the early 1900s, Rossini received tributes from Ottorino Respighi, who arranged parts of the Péchés de viellesse for his ballet la boutique fantasque (1918) and his 1925 suite Rossiniana. Benjamin Britten also adapted Rossini's music for two suites, Soirées musicales (1937) and Matinées musicales (1941). A three-volume biography of Rossini by Giuseppe Radiciotti (1927–1929) was an important turning point towards a more positive view of his work.

A strong re-evaluation of Rossini's importance began later in the 20th century, thanks to new studies and critical editions of his works. A key organization in this was the "Fondazione G. Rossini," created by the city of Pesaro in 1940 with funds left by the composer. Since 1980, the "Fondazione" has supported the annual Rossini Opera Festival in Pesaro.

In the 21st century, opera houses worldwide still mostly perform Il barbiere. La Cenerentola is the second most popular. Several other operas are regularly produced, including Le comte Ory, La donna del lago, La gazza ladra, Guillaume Tell, L'italiana in Algeri, La scala di seta, Il turco in Italia, and Il viaggio a Reims. Other Rossini pieces performed from time to time include Adina, Armida, Elisabetta regina d'Inghilterra, Ermione, Mosé in Egitto, and Tancredi. The Rossini in Wildbad festival specializes in performing his rarer works. All of Rossini's operas have been recorded.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Gioachino Rossini para niños

In Spanish: Gioachino Rossini para niños