Russian Armenia facts for kids

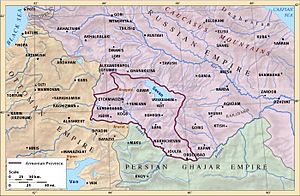

Russian Armenia refers to the time when parts of Armenia were under Russian rule. This period began in 1828. Before that, Eastern Armenia was part of the Persian Empire. After losing a war with Russia (the Russo-Persian War (1826–1828)), Persia had to give up these lands. This was agreed in the Treaty of Turkmenchay in 1828.

Eastern Armenia remained part of the Russian Empire until it fell apart in 1917.

Contents

- A Look Back in Time

- Russia Takes Over Armenian Lands

- How Russia Ruled Armenia

- Armenians in the Russian Empire

- Russian Rule Until 1877

- The Russo-Turkish War

- The Reign of Alexander III (1881–1894)

- The Reign of Nicholas II (1894–1917)

- World War I and Independence (1914–1918)

- Soviet Rule

- Images for kids

- See also

A Look Back in Time

For many centuries, people in Eastern Armenia lived under different Iranian empires. From the early 1500s until 1828, Eastern Armenia was ruled by the Safavid, Afsharid, and Qajar families of Iran. Wars between the Ottoman and Safavid empires often destroyed Armenian towns. This made life very hard for Armenians. Also, Christian Armenians were non-Muslim subjects under Muslim rulers. They had certain rules to follow.

In 1678, Armenian leaders secretly met in Echmiadzin. They decided Armenia needed to be free from foreign control. They couldn't fight two empires at once, so they looked for help from other countries. Israel Ori, an Armenian prince from Karabagh, traveled to many European capitals seeking support. He died in 1711, before his dream for Armenia came true.

In 1722, Peter the Great, the Tsar of Russia, declared war on the Safavid Iranians. The Safavid Empire was very weak at this time. Georgians and Armenians from Karabagh helped the Russians. They rebelled against Safavid rule. David Bek led this rebellion for six years until he died in battle.

Russia Takes Over Armenian Lands

A big change happened in 1801. Russia took over the Georgian Kingdom of Kartli-Kakheti. This gave Russia a strong position in the Transcaucasia region. Over the next 30 years, Russia wanted to expand its land in the Caucasus. They aimed to take land from Ottoman Turkey and Qajar Iran. Armenians were very supportive of Russia's campaigns. Bishop Nerses Ashtaraketsi from Tbilisi even joined the fighting himself.

The Russo-Persian War (1804–1813) saw Russia gain some land in Eastern Armenia. But they gave most of it back in the Treaty of Gulistan.

In 1826, Russia took parts of Iran's Erivan Khanate. This started the last war between the two empires: the Russo-Persian War (1826–1828). Iran suffered a huge defeat. Russia even occupied Tabriz in Iran. The war ended in 1828 with the Treaty of Turkmenchay. Iran was forced to give up its lands, including the Erivan Khanate (which is modern-day Armenia) and the Nakhichevan Khanate. By 1828, Iran's rule over Eastern Armenia officially ended.

Population Changes

Until the late 1400s, Armenians were the main group in Eastern Armenia. But by the end of the 1400s, Islam became the main religion. Armenians then became a smaller group in Eastern Armenia.

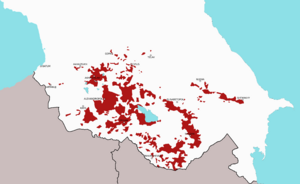

About 80% of the people in Iranian Armenia were Muslims (Persians, Turkic people, and Kurds). Christian Armenians made up only about 20%. This was mainly because of wars with the Ottomans in the 1500s. Also, in the early 1600s, Shah Abbas I forced many Armenians to leave the region.

After Russia took control of Iranian Armenia, the population mix changed. For the first time in 300 years, ethnic Armenians started to become the majority again in this part of historic Armenia. The new Russian government encouraged Armenians to return from Iran and Anatolia. By 1832, the number of Armenians was similar to the number of Muslims.

After the Crimean War and the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878), even more Turkish Armenians moved to the area. This helped Armenians become a strong majority in Eastern Armenia. However, the city of Erivan still had more Muslims than Armenians until the 1900s.

How Russia Ruled Armenia

Armenian leaders like Bishop Nerses hoped for Armenia to be a self-governing region within the Russian Empire. But they were disappointed. Tsar Nicholas and his governor, Ivan Paskevich, wanted Russia to be a strong, central state. When Nerses complained, he was sent far away to Bessarabia.

In 1836, the Russian government passed a rule called the Polozhenie (charter). This rule greatly reduced the political power of Armenian religious leaders, including the Catholicos. However, it did keep the Armenian Church somewhat independent. After 1836, the Catholicos of Echmiadzin was chosen in meetings where both religious and non-religious leaders took part. But the Tsar had the final say in who became Catholicos.

Armenians benefited because the Catholicosate kept the power to open schools. Famous ones include the Lazarian School in Moscow and the Nersessian school in Tiflis. The Catholicosate also opened printing houses and encouraged Armenian newspapers.

Armenians in the Russian Empire

Many Armenians already lived in the Russian Empire before the 1820s. After the last independent Armenian states fell in the Middle Ages, the Armenian noble families disappeared. Armenian society then mostly consisted of farmers and a middle class of craftsmen or merchants. These Armenians lived in most towns in Transcaucasia. In the early 1800s, they were even the majority in cities like Tbilisi.

Armenian merchants traded all over the world. Many had set up businesses in Russia. In 1778, Catherine the Great invited Armenian merchants from the Crimea to Russia. They started a settlement called Nor Nakhichevan near Rostov-on-Don. Russian rulers liked the Armenians' business skills because it helped the economy. But they also watched them with some suspicion. Armenians were sometimes seen as "clever merchants."

However, middle-class Armenians did well under Russian rule. They were quick to use new chances to become wealthy when capitalism and factories came to Transcaucasia in the late 1800s. Armenians were better at adapting to these new economic times than their neighbors, the Georgians and Azeris. They became very powerful in the city life of Tbilisi, which Georgians considered their capital. In the late 1800s, Armenians started buying land from Georgian nobles, who were losing their wealth.

Armenian business owners quickly used the oil boom that began in Transcaucasia in the 1870s. They invested a lot in oil fields in Baku (Azerbaijan) and oil refineries in Batumi on the Black Sea coast. This meant that tensions between Armenians, Georgians, and Azeris in Russian Transcaucasia were not just about ethnicity or religion. They were also about social and economic differences. Still, even with the image of Armenians as successful business people, 80% of Russian Armenians were still farmers at the end of the 1800s.

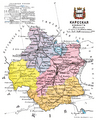

Russian Rule Until 1877

Relations between Russian authorities and their new Armenian subjects were not easy at first. Armenia was on Russia's border with the Ottoman and Persian empires. So, it was treated like a military zone. Until 1840, Russian Armenia was a separate area called the Armenian Oblast. But then it was combined with other Transcaucasian provinces. This was done without caring about its Armenian identity.

Things got better when Nerses Ashtaraketsi was brought back from Bessarabia. He became the Catholicos of the Armenian Church in 1843. Also, Mikhail Vorontsov, who was the Viceroy of the Caucasus from 1845 to 1854, was very friendly towards Armenians.

Because of this, by the mid-1800s, most Armenian thinkers and educated people became very pro-Russian. Armenian culture grew during these years. Being part of the Russian Empire gave Armenians a sense of shared identity again. It also turned Armenia's focus away from the Middle East and towards Europe. New ideas like the Enlightenment and Romanticism became popular. Many Armenian newspapers were published. There was a literary rebirth led by Mikael Nalbandian, who wanted to modernize the Armenian language. The poet and writer Raffi was also important. Armenian thinkers continued to support Russia under Tsar Alexander II, who was praised for his reforms.

The Russo-Turkish War

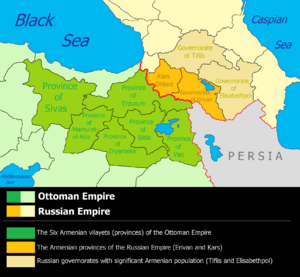

The Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878) changed the relationship between Russian authorities and Armenians. Armenians still living in western Armenia under the Ottoman Empire were increasingly unhappy. They hoped Russia would free them from Turkish rule.

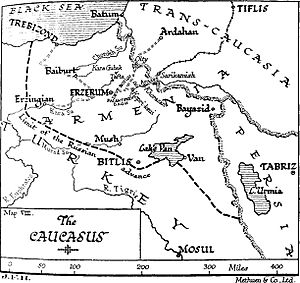

In 1877, war broke out between Russia and the Ottomans. The war was about how Christians were treated in the Balkans. Russia wanted to use Armenian patriotism when they attacked the Turks in the Caucasus. Many of the Russian commanders were of Armenian descent. Russia gained a lot of land in western Armenia before a ceasefire in January 1878.

The Treaty of San Stefano, signed in March 1878, did not give Russia all of western Armenia. But it had a special rule, Article 16. This rule said Russia would protect the rights of Armenians still under Ottoman rule. However, other powerful countries like Great Britain and Austria were worried about Russia's gains. They pushed for changes to the treaty. At the Congress of Berlin, Russia had to give up most of its Armenian gains. Only the regions of Kars and Ardahan remained Russian. Article 16 was replaced by Article 61. This new rule said that reforms in Ottoman Armenian provinces would only happen after the Russian army left.

The Reign of Alexander III (1881–1894)

After Tsar Alexander II was killed in 1881, the Russian government's attitude towards the empire's minority groups changed a lot.

The new tsar, Alexander III, was very traditional. He wanted to create a strong, central state where he had all the power. He saw any desire for more freedom from his subjects as a sign of rebellion.

Russification

The late 1800s also saw a rise in Russian nationalism. Non-Russians were often described in negative ways. Armenians faced particular unfair treatment, similar to anti-Jewish feelings. The first sign of this was the new government firing Alexander II's main minister, the Armenian Count Loris-Melikov. He was seen as too liberal. He was also called "a wild Asian" and "not a true Russian patriot."

Russian authorities also started to suspect Armenian economic power in Transcaucasia. This was ironic because Armenians were among the most pro-Russian subjects. But these suspicions led Russia to create policies that caused the very thing they wanted to prevent. Armenians started to turn more and more towards new nationalist movements.

Russification truly began in 1885. The Viceroy of the Caucasus, Dondukov-Korsakov, ordered all Armenian church schools to close. They were to be replaced by Russian schools. Although Armenian schools reopened the next year, they were now strictly controlled by the Tsar. The use of the Armenian language was discouraged in favor of Russian. Russians also began to treat the Armenian Church badly. The Armenian Church had been separate from the Orthodox Church since 451 AD.

Russia's view of the Ottoman Empire also changed. By the 1890s, Russia and Britain had switched roles. Now Russia supported the existing situation in western Armenia. Britain was the one urging better conditions for Christians there. Russian authorities were worried about Armenian nationalist groups in the Ottoman Empire. They feared these groups would connect with Eastern Armenians and cause trouble in Russian Transcaucasia. The Tsar's government stopped any attempts by Russian Armenians to act across the border. A key example was the Gugunian Expedition of 1890.

The Rise of Armenian Nationalism

Armenians played a small role in Russian revolutionary movements until the 1880s. Before that, the ideas of Grigor Artsruni were very popular among Armenian thinkers. Artsruni was the editor of the Tbilisi newspaper Mshak ("The Cultivator"). He believed that living under the Russian Empire was the "lesser evil" for his people.

Russian Armenians were very concerned about their fellow Armenians under the Persian and Ottoman Empires. Especially the farmers in western Armenia, who were often ignored by Armenian intellectuals in Istanbul and Smyrna. Tbilisi and Yerevan were much better places to start revolutionary activities among Armenians in the eastern Ottoman Empire. The idea of uniting Armenia, which was split between three empires, meant that Armenian political groups would be different from other Russian Empire movements.

The growth of Armenian nationalism was boosted by Russia's anti-Armenian actions in the 1880s. In 1889, Christapor Mikaelian started the "Young Armenia" movement in Tbilisi. Its goals were to punish Kurds who were believed to be harming Armenians in the Ottoman Empire. They also smuggled weapons and encouraged guerrilla fighting. They connected with a new Ottoman Armenian nationalist party, the Hunchaks.

In 1890, Mikaelian and Simon Zavarian replaced Young Armenia with a new party: the Armenian Revolutionary Federation, also known as the "Dashnaks." The Dashnaks tried to get the Hunchaks to join them, but they split in 1891. Rivalry between these parties would be a big part of Armenian nationalism later on. Both parties had socialist economic plans. However, the Dashnaks' main focus was nationalism. Their biggest concern was the fate of the Ottoman Armenians. They soon had branches in Russia, Persia, and Turkey. After the Hunchaks split in the mid-1890s, the Dashnaks became the main nationalist group in Russian Armenia.

The Reign of Nicholas II (1894–1917)

Tsar Nicholas II, who became ruler in 1894, continued his father's policy of Russification. Anti-Armenian feelings also grew among Georgians and Azeris in Transcaucasia. This was made worse by V.L. Velichko, the editor of the official newspaper Kavkaz ("Caucasus"), who was a strong Russian nationalist.

Church Property Confiscation (1903–1904)

In 1897, Tsar Nicholas appointed Grigory Sergeyevich Golitsin as governor of Transcaucasia. Golitsin disliked Armenians. Armenian schools, cultural groups, newspapers, and libraries were closed. Armenian nationalism, especially the Dashnaks' use of violence and socialist ideas, had not appealed much to wealthy Armenians at first. But Russian cultural repression made them more sympathetic. Wealthy Armenians who had adopted Russian ways started changing their names back to Armenian forms. They hired private teachers to teach their children Armenian.

The Tsar's Russification plan reached its peak on June 12, 1903. He ordered the government to take over the properties of the Armenian Church. The Catholicos of Armenia asked the Russians to cancel the order. When they refused, he turned to the Dashnaks. The Armenian clergy had been very careful around the Dashnaks before. They had said the Dashnaks' socialism was against the church. But now, they saw the Dashnaks as their protectors.

The Dashnaks formed a Central Committee for Self-Defence in the Caucasus. They organized many protests among Armenians. In Gandzak, the Russian army fired into the crowd, killing ten people. More protests led to more bloodshed. The Dashnaks and Hunchaks began to kill Russian officials in Transcaucasia. They even managed to wound Prince Golitsin. In 1904, the Dashnak meeting decided to also protect the rights of Armenians within the Russian Empire, not just Ottoman Turkey.

The 1905 Revolution

Trouble in Transcaucasia, including big strikes, reached its highest point during the Russian Revolution of 1905. This year saw many rebellions, strikes, and farmer uprisings across the Russian Empire. Events in Transcaucasia were especially violent. In Baku, a center for Russia's oil industry, class tensions mixed with ethnic rivalries. The city was almost entirely made up of Azeris and Armenians. But the Armenian middle class often owned more of the oil companies. Armenian workers generally had better pay and working conditions than Azeris.

In December 1904, after a major strike in Baku, the two groups started fighting each other in the streets. The violence spread to the countryside. By the time it ended, about 1,500 Armenians and 700 Azeris had died. The events of 1905 convinced Tsar Nicholas that he needed to change his policies. He replaced Golitsin with Count Illarion Ivanovich Vorontsov-Dashkov, who was friendly to Armenians. He also returned the Armenian Church's property. Slowly, order was restored. The wealthy Armenians again started to distance themselves from the revolutionary nationalists.

Tribune of People, 1912

In January 1912, 159 Armenians were accused of being part of an anti-government group. During the revolution, Armenian revolutionaries were split. Some were "Old Dashnaks" who sided with the Kadets. Others were "Young Dashnaks" who sided with the SRs. All Armenian national groups were put on trial. This included Armenian writers, doctors, lawyers, bankers, and even merchants. When the trials finished, 64 charges were dropped. The rest of the accused were either jailed or sent away for different periods.

World War I and Independence (1914–1918)

The years between the 1905 Revolution and World War I saw most Armenians and Russian authorities become friends again. Russia became worried when its enemy, Germany, grew closer to the Ottoman Empire. This made Russia take a new interest in the well-being of Ottoman Armenians.

When World War I started in August 1914, Russia tried to use Armenian patriotism. Most Armenian soldiers were sent to fight on the Eastern Front in Europe. The Ottoman Empire did not join the war for several months. As the possibility of a Caucasus Campaign grew closer in the summer of 1914, Count Illarion Ivanovich Vorontsov-Dashkov talked with the Mayor of Tbilisi, Alexandre Khatsian, Bishop Mesrop, and civic leader Dr. Hakob Zavriev. They discussed creating Armenian volunteer groups. These groups would be made of Armenians who were not Russian citizens or not required to serve in the army. These units would fight in the Caucasus Campaign. Many Armenians in the Caucasus were eager to fight to free their homeland. During the war, 150,000 Armenians fought in the Russian Army.

Occupation of Turkish Armenia

The Ottoman authorities began the killing of their Armenian subjects as early as April 1915. This followed the quick Russian advance in the Caucasus Campaign and the Siege of Van. An Armenian temporary government was first set up around Lake Van. This Armenian government in the war zone was briefly called "Free Vaspurakan." After an Ottoman advance in June 1915, 250,000 Armenians from Van and the nearby region of Alashkerd fled to the Russian border. Russian Transcaucasia was filled with refugees from the massacres.

While Russia had military successes against the Turks, its war effort began to fall apart on the front against Germany. In February 1917, the Tsar's government was overthrown by a revolution in Saint Petersburg.

Russian Armenians welcomed the new government. They hoped it would secure Ottoman Armenia for them. The question of continuing the war was very debated among Russia's new political parties. Most wanted a "democratic peace." But since parts of Ottoman Armenia were under Russian military control during the revolution, Armenians believed the government would defend them. To help, the new government started replacing Russian troops, who were losing their will to fight, with Armenian ones on the Caucasian front. But as 1917 went on, the new government lost support among Russian soldiers and workers. Much of the army left Transcaucasia.

Armenian Congress of Eastern Armenians

The Bolshevik Revolution in October 1917 forced the issue of independence for the people of Transcaucasia. This was because the Bolsheviks had little support in the region. In February 1918, Armenians, Georgians, and Azeris formed their own Transcaucasian parliament. Armenians united under the Armenian Congress of Eastern Armenians. On April 22, 1918, it voted for independence. It declared itself the Democratic Federative Republic of Transcaucasia. This federation broke up when Georgia declared its independence on May 26. The Armenian Congress of Eastern Armenians followed on May 28.

The Armenian Congress of Eastern Armenians made plans to guide the war efforts. They also worked on helping and returning refugees. The council passed a law to organize the defense of the Caucasus against the Ottoman Empire. They used the large amount of supplies and weapons left behind by the Russian army. The congress specifically created a local control and administrative system for Transcaucasia. Even if the Congress didn't make specific plans for soldiers in Baku, Tbilisi, Kars, and other militias under the Occupation of Turkish Armenia, they did not stop these soldiers from serving other forces. The Congress also chose a 15-member permanent committee, called the "Armenian National Council." Its leader was Avetis Aharonyan. This committee's first job was to prepare for the declaration of the First Republic of Armenia.

First Republic of Armenia

The biggest problem for the new state was the advancing Ottoman army. This army had already taken back much of western Armenia. But the interests of the three peoples were very different. For Armenians, defending against the invading army was most important. Muslim Azeris were sympathetic to the Turks. Georgians felt they could best protect themselves by making a deal with the Germans rather than the Turks. So, on May 26, 1918, with German encouragement, Georgia declared its independence from the Transcaucasian Republic. Azerbaijan followed two days later. Reluctantly, the Dashnak leaders, who were the most powerful Armenian politicians, declared the formation of a new independent state. This was the First Republic of Armenia, declared on May 28, 1918.

Republic of Mountainous Armenia

The Treaty of Batum was signed between the First Republic of Armenia and the Ottoman Empire. This happened after the last battles of the Caucasus Campaign. The Ottoman Empire first gained a large part of the South Caucasus with the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk signed with Russia. Then they gained more with the Treaty of Batum with Armenia.

Andranik Ozanian did not accept these new borders. He declared a new state. His activities were focused on the area connecting the Ottoman Empire to the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic. This area included Karabakh, Zanghezur, and Nakhichevan. In January 1919, as Armenian troops advanced, British forces ordered Andranik back to Zangezur. They promised him that this conflict could be solved at the Paris Peace Conference of 1919. The Paris Peace Conference declared the First Republic of Armenia an internationally recognized state. The Republic of Mountainous Armenia then ended.

Centrocaspian Dictatorship

The Centrocaspian Dictatorship was a government supported by the British. It was founded in Baku on August 1, 1918, and was against the Soviets. The government was made up of the Socialist-Revolutionary Party and the Armenian national movement. Most of the Armenians were from the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (Dashnaks). British forces occupied the city and helped the mainly Dashnak-Armenian forces defend the capital during the Battle of Baku. However, Baku fell on September 15, 1918. An Azeri-Ottoman army entered the capital, causing British forces and many Armenians to flee. The Ottoman Empire signed the Armistice of Mudros on November 30, 1918. The British forces then re-entered Baku.

Soviet Rule

Eventually, the USSR took over Eastern Armenia. It became known as the Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Armenia rusa para niños

In Spanish: Armenia rusa para niños

- History of Armenia

- Timeline of Armenian history

- Armenian Oblast

- Erivan Governorate

- Elisabethpol Governorate

- Kars Oblast (since 1878)

| Lonnie Johnson |

| Granville Woods |

| Lewis Howard Latimer |

| James West |