Spanish conquest of Nicaragua facts for kids

The Spanish conquest of Nicaragua was a time when Spanish explorers and soldiers, called conquistadores, came to the land we now know as Nicaragua. They met the native people who already lived there. This happened in the early 1500s, during the time when Spain was exploring and settling many parts of the Americas.

Before the Spanish arrived, different groups of native people lived in Nicaragua. In the west, there were groups like the Chorotega, the Nicarao, and the Subtiaba. Other groups included the Matagalpa.

The first Spanish explorer to reach Nicaragua was Gil González Dávila in 1522. He had permission from the governor of a nearby Spanish area, but the Chorotega people made him go back to his ships. In 1524, another Spanish leader, Francisco Hernández de Córdoba, started the Spanish towns of León and Granada. For about 30 years, most of the Spanish activity was in western Nicaragua, near the Pacific Ocean. Sadly, within 100 years, most of the native people were gone. This was due to fighting, diseases brought by the Europeans, and being taken away as slaves.

Contents

- Nicaragua's Land and Weather

- Native Peoples Before the Spanish Arrived

- Why the Spanish Came to Nicaragua

- The Conquistadors and Their Tools

- Early Explorations of Nicaragua (1519–1523)

- Rival Plans for Nicaragua (1523)

- Hernández de Córdoba in Western Nicaragua (1523–1525)

- Pedrarias Dávila Takes Control (1526–1529)

- Central Highlands (1530–1603)

- Eastern Nicaragua: Beyond Spanish Control

- What Happened After the Conquest

- How We Know About the Conquest

Nicaragua's Land and Weather

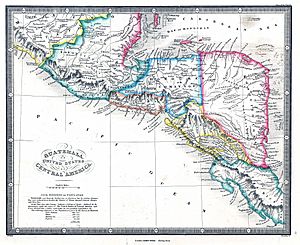

Nicaragua is the biggest country in Central America. It covers about 129,494 square kilometers (49,998 square miles). It shares borders with Honduras to the north and Costa Rica to the south. The Pacific Ocean is to its west, and the Caribbean Sea is to its east.

Nicaragua has three main areas:

- The Pacific Lowlands in the west.

- The Central Highlands in the middle.

- The Caribbean Lowlands in the east.

The Pacific lowlands are mostly flat land along the coast, stretching about 75 kilometers (47 miles) inland. A line of volcanoes runs through this area, many of them still active. These volcanoes are along the edge of a rift valley that goes all the way to the San Juan River. This river forms part of the border with Costa Rica.

Two large lakes are in this rift valley: Lake Managua and Lake Nicaragua. Lake Managua is about 56 by 24 kilometers (35 by 15 miles). Lake Nicaragua is much larger, about 160 by 75 kilometers (99 by 47 miles). The Tipitapa River connects Lake Managua to Lake Nicaragua. From Lake Nicaragua, the San Juan River flows into the Caribbean Sea.

The Central Highlands have mountains that can reach up to 2,000 meters (6,600 feet) high. This area has several mountain ranges.

Nicaragua's Climate

In central Nicaragua, the temperature is usually between 20 and 25 degrees Celsius (68 and 77 degrees Fahrenheit). It rains about 1,000 to 2,000 millimeters (39 to 79 inches) each year. There is a dry season for four months, and then it rains for the rest of the year.

Before the Spanish arrived, the Central Highlands were covered in pine forests. The Pacific coast had tropical dry forests with rich volcanic soil. The Atlantic lowlands get more rain. The soil there is not as rich, and it has tropical moist forests.

Native Peoples Before the Spanish Arrived

When the Spanish first came to Nicaragua, three main native groups lived in the western part of the country: the Chorotega, the Nicarao, and the Matagalpa.

The Nicarao people spoke a language called Nawat. They had moved south from central Mexico starting in the 700s AD. They settled along the Pacific Coast of western Nicaragua, especially in the Rivas area. The Chorotega people also came from Mexico and spoke the Mangue language. The Subtiaba were another group from Mexico, speaking the Subtiaba language.

The Matagalpa people were different. They lived in the Central Highlands. They spoke a Misumalpan language and were part of the Chibchoidean culture. They lived in areas that are now the departments of Boaco, Chontales, Estelí, Jinotega, Matagalpa, and parts of Nueva Segovia. The Matagalpa were organized into tribes and chiefdoms. They often fought with other tribes. When the Spanish arrived, they were fighting the Nicarao.

Eastern Nicaragua was home to other groups, like the Rama (Chibchoidean) and the Mayangna and Miskito (Misumalpa). These groups were culturally linked to South American peoples.

Historians believe about 825,000 native people lived in Nicaragua when the Spanish arrived. In the first 100 years after the Spanish came, the native population dropped very sharply. This was mainly because of diseases brought from Europe and because many were taken as slaves. Fighting and harsh treatment also played a part. Some experts say that 99% of the native people in western Nicaragua died within 60 years.

Native Weapons and Fighting Styles

The Spanish described the Matagalpa people as well-organized in battle. The Nicarao people fought with the Matagalpa, possibly to capture people to be used as slaves or for religious ceremonies.

Why the Spanish Came to Nicaragua

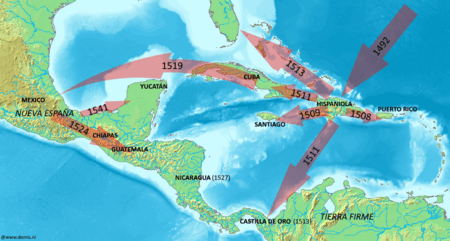

Christopher Columbus found the "New World" for Spain in 1492. After this, Spanish adventurers made deals with the King and Queen of Spain. They would conquer new lands in exchange for a share of the wealth and the power to rule. The Spanish built their first main town, Santo Domingo, on the island of Hispaniola in the 1490s. In the early 1500s, they took control of the Caribbean Sea islands, using Cuba as a base.

From these islands, the Spanish launched expeditions to the mainland. They reached Puerto Rico in 1508, Jamaica in 1509, Cuba in 1511, and Florida in 1513.

In the south, the Spanish settled in Castilla de Oro (which is now Panama). Vasco Núñez de Balboa founded a town there in 1511. In 1513, Balboa discovered the Pacific Ocean. Later, in 1519, Pedrarias Dávila founded Panama City on the Pacific coast. From Panama, the Spanish began exploring north along the Pacific coast.

The Spanish heard stories of the rich Aztec Empire in Mexico. In 1519, Hernán Cortés sailed to Mexico. By 1521, the Aztec capital, Tenochtitlan, had fallen to the Spanish. Within three years, the Spanish had conquered a large part of Mexico. This new land became New Spain, ruled by a viceroy who reported to the Spanish Crown.

The discovery of the Aztec Empire and its riches made the Spanish in Panama look north. Several expeditions were sent, led by important conquistadors like Pedrarias Dávila, Gil González Dávila, and Francisco Hernández de Córdoba.

The Conquistadors and Their Tools

The conquistadors were volunteers. Most did not get a regular salary. Instead, they received a share of what they conquered, like gold, land, and native workers. Many of these Spanish soldiers had fought in wars in Europe before.

Pedrarias Dávila was a nobleman from a powerful family. Gabriel de Rojas was one of Dávila's officers. He had fought in other Spanish conquests. Not much is known about Francisco Hernández de Córdoba. He was probably a commoner who became important because of his actions in the New World. Gil González Dávila was a professional soldier. Hernando de Soto was a nobleman who later explored Florida.

Spanish Weapons and Armor

Spanish conquistadors in the 1500s used broadswords, rapiers, crossbows, and early guns called matchlocks. They also had light artillery (cannons). Soldiers on horseback used long lances. Other weapons included halberds and bills.

Metal armor was heavy and rusted easily in the hot, wet climate. It also got very hot in the sun. So, conquistadors often wore quilted cotton armor, similar to what the native people used. They often wore a simple metal war hat for protection. Shields were very important for both foot soldiers and cavalry. These were usually round shields made of iron or wood.

The Church's Role

The Spanish said their reason for conquering new lands was to convert the native people to Christianity. The Spanish Crown and the Church believed that native people had souls and deserved rights. However, the colonists often treated them as less than human and forced them to work. This led to disagreements between Spain and the colonists.

Religious figures were part of the conquest from the start. Father Diego de Agüero went with Gil González in 1519 and returned with Francisco Hernández de Córdoba in 1524. One of the first things the Spanish did in a native village was to place a cross on top of the local shrine. This showed that the Church's authority was replacing the native religion.

Early Explorations of Nicaragua (1519–1523)

Spanish explorers first saw the Pacific coast of Nicaragua in 1519. They were sailing north from Panama. That year, Pedrarias Dávila took control of ships belonging to another explorer. He sent two ships, San Cristóbal and Santa María de la Buena Esperanza, to explore west. The ships reached the Gulf of Nicoya in October 1519. This gulf later became an important way for expeditions to enter Nicaragua.

This first trip did not set up a Spanish settlement. Native warriors in canoes and on shore showed they were ready to fight. So, the ships turned back to Panama. The Spanish did manage to capture a few native people. They took them back to Panama to learn Spanish and become interpreters.

Gil González Dávila's Journey

In 1518, the Spanish Crown gave Gil González Dávila and Andrés Niño permission to explore the Pacific coast. They left Spain in 1519. They built their own ships in Panama. On January 21, 1522, they traveled northwest through Costa Rica and into southwestern Nicaragua.

Their journey was slow. Their ships were damaged, and their water went bad. They decided to split up. Andrés Niño repaired the ships and explored the coast. Gil González went inland with 100 Spaniards and 400 native helpers. They met up again at the Gulf of Nicoya. Here, they noticed that the native people had customs similar to those in the Yucatán Peninsula.

González was sick, but his men wanted to keep going by land. They used one ship to cross to the western side of the Gulf of Nicoya. The native people there welcomed them. González continued inland with 100 Spaniards and 4 horses.

Exploring the Pacific Coast

While Gil González Dávila marched inland, Andrés Niño sailed with two ships. On February 27, 1523, Niño landed at El Realejo. A Spanish captain officially claimed the land for Spain. This was the first Spanish act in what is now Nicaragua. They faced no resistance. To remember this, they named the place Posesión.

Niño continued sailing and landed on an island in the Gulf of Fonseca on March 5. He named the gulf after a Spanish bishop. Niño sailed as far north as the Isthmus of Tehuantepec in Mexico.

Journey Inland and First Encounters

Meanwhile, on his march inland, Gil González heard about a powerful native leader named Nicarao. Nicarao ruled many warriors. González decided to keep going until he met him. Nicarao met Gil González outside his capital city, Quauhcapolca, and welcomed him peacefully. The two leaders exchanged gifts. González said he received a lot of gold. The Spanish captain gave Nicarao silk clothes and other items from Spain.

For several days, the Spanish taught the native people about Christianity. González claimed that over 9,000 people, including adults and children, were baptized in one day. After this, González learned about Lake Nicaragua. He sent soldiers to check if it was real, then went there himself. On April 12, 1523, they claimed the lake for Spain, calling it Mar Dulce ("sweet sea"). They thought the lake might connect to the Caribbean Sea, which would be a new route across Central America. Many native people came to see the Europeans, curious about their strange appearance, clothes, and horses, which they had never seen before.

Native Resistance and Spanish Retreat

From Quauhcapolca, Gil González Dávila went to another native village near the Mombacho volcano. Here, he met another powerful leader, Diriangén, who led the Chorotega people. Diriangén came with many richly dressed followers. He said he wanted to see the bearded strangers and their animals.

Diriangén returned three days later, on April 17, ready for battle. The Spanish were warned by a local native. Even so, a fierce fight began, and several Spanish soldiers were hurt. Their few horses helped them, as they scared the enemy. The Chorotega attack was pushed back. González immediately called back a group of soldiers who had gone ahead.

The strong resistance from the Chorotega convinced González and his officers to turn back with the gold they had collected. They marched back south through Nicarao territory, now wary of all native activity. They marched in a defensive formation. The wounded soldiers and supplies were in the middle, protected by the fittest soldiers. They met passive resistance from natives they passed, until they met some Nicarao nobles who apologized for the hostility. González accepted the apology because his forces were vulnerable. They spent the night on a hilltop, ready for attack. The next day, they continued their retreat through empty lands until they reached their ships on the Pacific coast.

Andrés Niño had returned to the ships a few days earlier. However, all the ships were in bad shape. The Spanish expedition had to make the difficult journey back to Panama in canoes. They arrived in Panama on June 23, 1523.

Gil González Dávila had discovered Lake Nicaragua, met Nicarao, and claimed to have converted thousands of native people to the Roman Catholic religion. He said a total of 32,000 natives were baptized. The expedition had also collected a large amount of gold, over 112,525 gold pesos.

Rival Plans for Nicaragua (1523)

Gil González Dávila wanted to return to Nicaragua quickly. But he faced problems from Pedrarias Dávila, the governor of Panama. Pedrarias Dávila had heard about the gold and quickly prepared a new expedition in late 1523. While González and Niño claimed the new lands for themselves, Pedrarias planned to take control before the Crown could approve their claims.

This new expedition was a private venture approved by the king. The participants signed a two-year contract in September 1523. Pedrarias Dávila would get one-third of the spoils. Francisco Hernández de Córdoba was put in charge. Pedrarias sent someone to Spain to get more men and horses. In Panama, he bought Andrés Niño's ships and supplies.

Meanwhile, González planned to return to Nicaragua by finding a river route from the Caribbean Sea to Lake Nicaragua. This would avoid Pedrarias Dávila's control. However, he ended up landing further west and starting the Spanish conquest of Honduras. Although González was the first to set foot in Nicaragua, Pedrarias Dávila based his claim on an earlier discovery of the territory by his men, Juan de Castañeda and Hernán Ponce de León.

Hernández de Córdoba in Western Nicaragua (1523–1525)

Francisco Hernández de Córdoba, following orders from Pedrarias Dávila, left Panama for Nicaragua in mid-October 1523. His expedition had over 200 men, including soldiers, cavalry, and about 16 African slaves.

In 1524, Hernández founded the Spanish towns of León and Granada. He founded Granada near the native town of Jalteba, and León in the middle of the native area of Imabite. We don't have direct stories about how these first towns were founded. It is known that the native people resisted, but we don't know how many battles were fought or who led the native resistance. Hernández likely followed Gil González Dávila's route from the Gulf of Nicoya to the Nicarao territory.

The expedition brought parts for a small ship called a brigantine. The Spanish put it together on the shores of Lake Nicaragua. The brigantine explored the lake and found that it did flow out to the Caribbean Sea through a river. However, the river was too rocky and had waterfalls, making it impossible to sail through. Still, the explorers confirmed the river's path and saw that the land was full of native groups and forests.

Hernández divided his forces into three groups. By May 1524, Hernández had reached Tezoatega (now El Viejo). Around this time, native people from the mountains, about 5 leagues (13 miles) from León, fought the Spanish but were defeated. León was likely founded after this, but before April 1525, when Hernández wrote to Pedrarias Dávila, saying he had already founded León and Granada. Spanish records from 1524 show that war prisoners were being sent to Panama as slaves, which suggests there was undocumented native resistance.

Disputes with Honduras (1524–1525)

While setting up Spanish control in Nicaragua, Hernández de Córdoba heard about a new Spanish presence to the north. Gil González Dávila had arrived in the Olancho Valley in Honduras. The borders of Nicaragua were not yet clear, and Gil González believed he was the rightful governor of that area.

Hernández sent Gabriel de Rojas to investigate. González told Rojas that neither Pedrarias Dávila nor Hernández de Córdoba had any rights over Honduras. Rojas reported this back to Hernández de Córdoba, who immediately sent soldiers under Hernando de Soto to capture González. However, González surprised de Soto with a night attack. Some of de Soto's men were killed, and González captured de Soto and a lot of gold.

Even though he won, González knew Hernández de Córdoba would not give up. He also heard that a new Spanish expedition had arrived on the north coast of Honduras. Not wanting to be surrounded by rivals, González freed de Soto and hurried north. Some of González's men left him and joined Hernández de Córdoba in Nicaragua.

Gabriel de Rojas stayed in Olancho into 1525, trying to extend Nicaragua's control there. He heard about new Spanish arrivals in Honduras, where Hernan Cortés, the conqueror of Mexico, had arrived to take charge. Rojas sent a letter and gifts to Cortés. Cortés at first seemed friendly. But when Rojas's men started stealing from the native people and enslaving them, Cortés sent his captain, Gonzalo de Sandoval, to order Rojas out of the area. Sandoval was told to capture Rojas or make him leave Honduras.

While the two groups were together, Rojas received orders from Hernández de Córdoba to return to Nicaragua. Hernández needed help against some of his own captains who were rebelling.

Hernández sent a second expedition into Honduras. This group was captured by Sandoval, who sent some of them to Cortés. They told Cortés that Hernández de Córdoba planned to rule Nicaragua independently from Pedrarias Dávila in Panama. Cortés was polite and offered supplies, but he sent letters telling Hernández de Córdoba to stay loyal to Pedrarias Dávila.

Hernández collected a lot of gold in Nicaragua, over 100,000 pesos in one trip. This gold was later taken by Pedrarias Dávila. By 1525, Spanish power was strong in western Nicaragua. More soldiers had arrived from Natá in Panama, which was an important port for ships between Nicaragua and Panama.

Problems in Nicaragua (late 1525)

The friendly talks between Hernán Cortés and Francisco Hernández de Córdoba made those loyal to Pedrarias Dávila in León very suspicious. These officers, like Hernando de Soto, thought Hernández de Córdoba was betraying Pedrarias Dávila. Hernández de Córdoba had founded three towns, which strengthened his claim over the area. This might have made Pedrarias Dávila see Hernández's contact with Cortés as a threat.

Rumors, spread by Hernández de Córdoba's enemies, quickly went around the colony that he was plotting with Cortés. About a dozen supporters of Hernando de Soto secretly planned against Hernández de Córdoba. Hernández responded by capturing de Soto and putting him in prison in Granada. De Soto and his friends escaped Nicaragua and went to Pedrarias Dávila in Panama, arriving in January 1526.

Pedrarias Dávila Takes Control (1526–1529)

Pedrarias Dávila sailed from Nata with soldiers and cannons. He landed on Chira Island in the Gulf of Nicoya. From there, he learned that Hernández de Córdoba had left the nearby Spanish settlement of Bruselas a few days earlier. Dávila waited on Chira for more soldiers led by Hernando de Soto. Dávila then arrested Hernández de Córdoba and ordered him to be executed.

In 1526, Pedrarias Dávila was replaced as governor of Castilla del Oro. Diego López de Salcedo, the governor of Honduras, tried to take control of Nicaragua. He marched to Nicaragua with 150 men and arrived in León in spring 1527. Pedrarias Dávila's officer there accepted him as governor. However, López de Salcedo's bad leadership made the colonists unhappy and caused the native people in northern Nicaragua to rebel.

Pedro de los Ríos, the new governor in Panama, also tried to take control of Nicaragua. But the colonists rejected him. Meanwhile, Dávila strongly protested to the Spanish king about losing his governorship. As a result, he was given the governorship of Nicaragua. López de Salcedo prepared to go back to Honduras, but the colonists in Nicaragua stopped him. They now supported Pedrarias Dávila. López de Salcedo's officials were arrested.

León became the capital of the Nicaraguan colony. Dávila moved there as governor in 1527. He arrived in León in March 1528 and was accepted as the rightful governor everywhere. He immediately imprisoned López de Salcedo for almost a year. Eventually, López de Salcedo was released and agreed to give up all claims to land beyond a certain line. This agreement settled the border disputes between Nicaragua and Honduras.

Pedrarias Dávila brought European farming methods to Nicaragua. He was known for his harsh treatment of the native people. From 1528 to 1529, a friar named Francisco de Bobadilla was very active. He baptized over 50,000 native people, including the Subtiaba and Nicarao.

Central Highlands (1530–1603)

In 1530, different Matagalpa tribes joined together to attack the Spanish. They wanted to burn the Spanish settlements. In 1533, Pedrarias Dávila asked for more soldiers to fight the Matagalpa and stop their rebellion. This was to prevent other native groups from joining them against the Spanish.

By 1543, Francisco de Castañeda founded Nueva Segovia in north-central Nicaragua, about 30 leagues (80 miles) from León. By 1603, the Spanish had control over seventeen native settlements in this north-central region, which they called Segovia. The Spanish forced warriors from these settlements to help them fight ongoing native resistance in Olancho, Honduras.

Eastern Nicaragua: Beyond Spanish Control

Soon after Europeans arrived, the Atlantic coast of Nicaragua came under the influence of the English. This region was home to native people who remained free from Spanish control. The Spanish called this area Tologalpa.

Tologalpa and Taguzgalpa together made up a large area along the Caribbean coast. It stretched from Trujillo to the San Juan River. Taguzgalpa was the part in modern Honduras, and Tologalpa was the part in modern Nicaragua. However, they were considered one province. From the mid-1600s, both regions were called Mosquitia. We know little about the original people of Mosquitia, but they included the Jicaque, Miskito, and Paya.

In 1508, Diego de Nicuesa was made governor of a region along the Caribbean coast. In 1534, another Spanish leader was given permission to conquer this area, but he gave up his plans. In 1545, the governor of Guatemala wrote to the king of Spain, explaining that Taguzgalpa was still outside Spanish control and that its people were a threat.

In 1641 or 1652, a slave ship was wrecked. The surviving Africans mixed with the native coastal groups, creating the Miskito Sambu. The Miskito Sambu formed strong ties with English colonists who settled in Jamaica from 1655 onwards. They became the most powerful group on the coast, making alliances or taking control of other groups.

When the Kingdom of Guatemala declared independence from Spain in 1821, most of Mosquitia was still not under Spanish control.

What Happened After the Conquest

Within 100 years of the conquest, the Nicarao people were almost completely gone. This was due to the slave trade, diseases, and warfare. It's thought that as many as half a million people were taken as slaves from Nicaragua before 1550. Some of these people had originally come from other parts of Central America.

Although Gil González Dávila found a good amount of gold at first, the Spanish hopes of finding huge amounts of gold in Nicaragua did not come true. Even when gold was found, the sharp drop in the native population meant there were not enough people to work in the mines. In 1533, the Spanish noted that a measles sickness had killed so many native people that there was no one left to dig for gold. By the end of the 1500s, Nicaragua had only about 500 Spanish colonists.

How We Know About the Conquest

Gil González Dávila wrote letters in 1524 describing his discovery of Nicaragua. One letter to the writer Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés gave a full account of his actions. Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés wrote a whole section about Nicaragua in his book General History of the Indies, published in 1535. He lived in Nicaragua himself for a year and a half.

Another writer, Antonio de Herrera y Tordesillas, described the first voyage of Gil González Dávila and Andrés Niño. Francisco Hernández de Córdoba's founding of León and Granada was described in a letter to the king from Pedrarias Dávila in 1525. The friar Bartolomé de las Casas also wrote about the discovery of Nicaragua. Juan de Castañeda wrote his own account of his journey in 1522.

| Jewel Prestage |

| Ella Baker |

| Fannie Lou Hamer |