Steamboats of the Colorado River facts for kids

Steamboats were a very important way to travel and move goods on the Colorado River. They operated from the river's mouth in Mexico all the way up to the Virgin River in the Southwestern United States. This happened from 1852 until 1909, when the Laguna Dam was finished. These special boats, called paddle steamers, were the cheapest way to ship items between ports on the Pacific Ocean and the towns and mines along the lower river.

They stopped at many places in Sonora state, Baja California Territory, California state, Arizona Territory, New Mexico Territory, and Nevada state. Steamboats were the main way to transport goods until railroads started to take over their business in 1878.

Some people tried to use steamboats on the upper Colorado River, in places like Glen Canyon and on the Green River in Utah and Wyoming. They also tried on the Grand River (which is now part of the Colorado River) in Utah and Colorado. But these attempts in the late 1800s and early 1900s were not very successful.

Contents

History of Colorado River Steamboats

Early Steamboats on the Colorado River

Why was Fort Yuma hard to supply?

The idea of using steamboats on the Colorado River came about because of problems supplying Fort Yuma during the Yuma War. Getting supplies to the fort was very difficult. They had to be shipped from San Francisco to San Diego, then traveled overland through mountains and across the dry Colorado Desert. This journey cost at least $500 per ton, which was a huge amount of money back then! It was so hard to supply the fort that it had to be left empty for a while.

The Army tried to bring supplies about 150 miles up from the Gulf of California. But these attempts failed because of strong tides, currents, shifting sandbars, or low water levels in the river. It was also against a treaty to bring American troops into Mexican territory, and there were extra taxes to pay.

The Uncle Sam and James Turnbull

In November 1852, a boat called the Uncle Sam became the first steamboat on the Colorado River. It was 65 feet long and had side-wheels. Captain James Turnbull brought it in pieces from San Francisco to the river's delta, where it was put together.

The Uncle Sam had a small 20-horsepower engine and could only carry 35 tons of supplies. Its first 120-mile trip took 15 days! Over time, it got faster, completing trips in 12 days. Sadly, the boat sank at its dock near Fort Yuma in the spring flood of 1853 and was washed away. Even though it sank, the Uncle Sam showed everyone that steamboats could solve the supply problems for Fort Yuma.

George A. Johnson & Company's Success

In late 1852, George Alonzo Johnson and his partners got the next contract to supply Fort Yuma. They learned from past mistakes and brought parts of a stronger side-wheel steamboat called the General Jesup. It was put together at the river's mouth and reached Fort Yuma on January 18, 1854. This new boat was a big success! It could carry 50 tons of cargo and made round trips from the river's mouth to the fort in just four or five days. This cut shipping costs down to $75 per ton.

One reason for the new steamboat's speed was the creation of "wood-yards" along the river. These were places where wood was gathered and stored for the steamboats to refuel. This meant the crew didn't have to stop and collect wood themselves. The wood-yards were often run by Americans who hired Cocopah people from local villages to cut wood (like cottonwood or mesquite) and load it onto the boats. Cocopah men also often worked as deck hands on the steamboats.

| Location | Distance |

|---|---|

| Philips Point, Sonora | 5 mi (8.0 km) |

| Port Isabel Slough from 1865 Port Isabel, Sonora 1867–1878 |

7 mi (11 km) |

| Robinson's Landing, Baja California 1854–1878 | 10 mi (16 km) |

| Hardy River | 23 mi (37 km) |

| Heintzelman's Point Head of Tidewater |

47 mi (76 km) |

| Port Famine, Sonora 1854–1878 | 50 mi (80 km) |

| Lerdo Landing, Sonora 1872–1896 | 53 mi (85 km) |

| Gridiron, Sonora 1854–1878 | 67 mi (108 km) |

| Ogden's Landing, Sonora 1854–1878 | 95 mi (153 km) |

| Hualapai Smith's, Sonora 1866–1878 | 105 mi (169 km) |

| Pedrick's, Arizona Territory 1854–1878 | 119 mi (192 km) |

| Jaeger City, California 1858–1862 Colorado City, Arizona Territory 1854–1862 |

149 mi (240 km) |

| Fort Yuma, California 1850–1883 Arizona City, Arizona Territory 1858–1873 Yuma, Arizona Territory from 1873 |

150 mi (240 km) |

The Route from the Delta to Fort Yuma

The steamboat journey started in the Colorado River Delta. At first, boats would anchor near Robinson's Landing in Baja California, about 10 miles from the river's mouth. Here, they would pick up cargo from other ships to avoid paying Mexican taxes. The strong tides and waves in this area made loading difficult and sometimes dangerous.

Over time, new landings and settlements grew along the river. In 1865, a better place for an anchorage and shipyard was built at Port Isabel, Sonora. This port was used until 1879, when the railroad reached Yuma, Arizona. Yuma then became the main port, and the older landings became unnecessary.

Expanding the Steamboat Route

After 1853, people started developing ranches and finding gold and copper mines upriver from Fort Yuma. This created more business for George A. Johnson & Co. By 1855, they needed another boat. So, they brought parts for a new steamboat called the Colorado from San Francisco. It was 120 feet long, had an 80-horsepower engine, and could carry 70 tons of cargo while only needing 2 feet of water. It was the first stern-wheeler (a boat with a paddle wheel at the back) on the river.

| Location | Distance |

|---|---|

| Potholes, California, From 1859 | 18 mi (29 km) |

| La Laguna, Arizona Territory, 1860–1863 | 20 mi (32 km) |

| Castle Dome Landing, Arizona Territory, 1863–1884 | 35 mi (56 km) |

| Eureka, Arizona Territory, 1863–1870s | 45 mi (72 km) |

| Williamsport, Arizona Territory, 1863–1870s | 47 mi (76 km) |

| Picacho, California, 1862–1910 | 48 mi (77 km) |

| Nortons Landing, Arizona Territory, 1882–1894 | 52 mi (84 km) |

| Clip, Arizona Territory, 1882–1888 | 70 mi (110 km) |

| California Camp, California | 72 mi (116 km) |

| Camp Gaston, California, 1859–1867 | 80 mi (130 km) |

| Drift Desert, Arizona Territory | 102 mi (164 km) |

| Bradshaw's Ferry, California, 1862–1884 | 126 mi (203 km) |

| Mineral City, Arizona Territory, 1864–1866 | 126 mi (203 km) |

| Ehrenberg, Arizona Territory, from 1866 | 126.5 mi (203.6 km) |

| Olive City, Arizona Territory, 1862–1866 | 127 mi (204 km) |

| La Paz, Arizona Territory, 1862–1870 | 131 mi (211 km) |

| Parker's Landing, Arizona Territory, 1864–1905 Camp Colorado, Arizona, 1864–1869 |

200 mi (320 km) |

| Parker, Arizona Territory, from 1908 | 203 mi (327 km) |

| Empire Flat, Arizona Territory, 1866–1905 | 210 mi (340 km) |

| Bill Williams River, Arizona | 220 mi (350 km) |

| Aubrey City, Arizona Territory, 1862–1888 | 220 mi (350 km) |

| Chimehuevis Landing, California | 240 mi (390 km) |

| Liverpool Landing, Arizona Territory | 242 mi (389 km) |

| Grand Turn, Arizona/California | 257 mi (414 km) |

| The Needles, Mohave Mountains, Arizona | 263 mi (423 km) |

| Mellen, Arizona Territory 1890–1909 | 267 mi (430 km) |

| Eastbridge, Arizona Territory 1883–1890 | 279 mi (449 km) |

| Needles, California, from 1883 | 282 mi (454 km) |

| Iretaba City, Arizona Territory, 1864 | 298 mi (480 km) |

| Fort Mohave, Arizona Territory, 1859–1890 Beale's Crossing 1858– |

300 mi (480 km) |

| Mohave City, Arizona Territory, 1864–1869 | 305 mi (491 km) |

| Hardyville, Arizona Territory, 1864–1893 Low Water Head of Navigation 1864–1881 |

310 mi (500 km) |

| Camp Alexander, Arizona Territory, 1867 | 312 mi (502 km) |

| Polhamus Landing, Arizona Territory Low Water Head of Navigation 1881–1882 |

315 mi (507 km) |

| Pyramid Canyon, Arizona/Nevada | 316 mi (509 km) |

| Cottonwood Island, Nevada Cottonwood Valley |

339 mi (546 km) |

| Quartette, Nevada, 1900–1906 | 342 mi (550 km) |

| Murphyville, Arizona Territory, 1891 | 353 mi (568 km) |

| Eldorado Canyon, Nevada, 1857–1905 Colorado City, Nevada 1861–1905 |

365 mi (587 km) |

| Explorer's Rock, Black Canyon of the Colorado, Mouth, Arizona/Nevada | 369 mi (594 km) |

| Roaring Rapids, Black Canyon of the Colorado, Arizona/Nevada | 375 mi (604 km) |

| Ringbolt Rapids, Black Canyon of the Colorado, Arizona/Nevada | 387 mi (623 km) |

| Fortification Rock, Nevada High Water Head of Navigation, 1858–1866 |

400 mi (640 km) |

| Las Vegas Wash, Nevada | 402 mi (647 km) |

| Callville, Nevada, 1864–1869 High Water Head of Navigation 1866–1878 |

408 mi (657 km) |

| Boulder Canyon, Mouth, Arizona/Nevada | 409 mi (658 km) |

| Stone's Ferry, Nevada 1866–1876 | 438 mi (705 km) |

| Virgin River, Nevada | 440 mi (710 km) |

| Bonelli's Ferry, 1876–1935 Rioville, Nevada 1869–1906 High Water Head of Navigation from 1879 to 1887 |

440 mi (710 km) |

Johnson also wanted to find a way to connect to the Mormon settlements in Utah by river. In 1856, he helped get money from Congress for a military trip up the river. The trip's leader, Lt. Joseph Christmas Ives, decided to build his own small steamboat, the Explorer. Johnson, however, decided to do his own trip upriver with the General Jesup. He had soldiers and armed civilians with him. They reached the first rapids in Pyramid Canyon, over 300 miles above Fort Yuma.

Ives followed Johnson, but his Explorer boat was not good at navigating the river's sandbars. It kept getting stuck. Johnson eventually bought the Explorer, took out its engine, and used it as a barge.

Gold Rush and New Steamboats

After a conflict called the Mohave War (1858–1859), and the building of Fort Mohave, people started settling along the upper river. The General Jesup and the Colorado steamboats were used to carry troops and supplies for the army. This became the first big reason for steamboats to travel upriver. Soon after, many gold and silver mines were discovered, leading to new towns and more business for the steamboats.

In 1858–1859, the first Arizona gold rush happened near Fort Yuma. This led to a new steamboat company trying to compete with Johnson's, but their boat and cargo were lost in the river's strong tides. In 1859, more gold was found near Fort Yuma. Johnson then replaced the General Jesup with a new, more suitable stern-wheeler called the Cocopah. It had a shallow design, which was perfect for the Colorado River. This design became the model for all future steamboats on the river.

Over the next few years, more gold was found along the Colorado River, making George A. Johnson and his partners very rich.

Steamboat Competition and Growth

The Civil War and Mining Boom

During the American Civil War (1861-1865), the Colorado River became even more important. Federal troops used Johnson's steamboats to move supplies and soldiers. This was a big source of income for Johnson's company.

At the same time, a huge mining boom started. In April 1861, silver and gold were found in El Dorado Canyon. Johnson made a deal to supply these mines with his steamboats, charging $100 per ton. This was much cheaper than moving goods overland.

More gold was discovered in January 1862, near La Paz, about 130 miles above Fort Yuma. This led to a big gold rush. Many new mining towns and landings appeared along the river, like Olive City and Hardyville. All these new mines and towns needed supplies, and the steamboats were the main way to get them.

New Competitors Join the River

By 1863, George A. Johnson and his partners were very wealthy. However, they hadn't increased the number of boats enough to handle all the new business. Goods were piling up at the river's mouth and at Arizona City, waiting to be shipped upriver. Steamboat captains even started buying goods themselves and selling them for high prices upriver, leaving other merchants' shipments behind.

Merchants and miners were upset about Johnson & Company's high prices and slow service. They held a meeting and decided to ask for a new steamboat company to compete. In San Francisco, a new company called the Union Line was formed. They brought a steamboat called the Esmerelda and a large tow barge called the Black Crook to the Colorado River. This was the first time a tow barge was used on the river, allowing boats to carry much more cargo.

Another company also put a steamboat on the river, the Nina Tilden, which was very fast and could carry a lot of cargo.

Competition and Mergers

Johnson realized the new competition was serious. He ordered a new steamboat, the Mohave, and tried to make it harder for his rivals by buying up all the wood at the wood-yards. He also lowered his shipping prices to compete.

With more boats on the river, the backlog of freight quickly disappeared. By late 1864, there were too many boats and not enough cargo, so boats were often sitting idle.

In 1865, the Esmerelda and Nina Tilden merged to form the Pacific and Colorado Steam Navigation Company. They tried to reach Callville, a landing that could connect to Utah settlements. The Esmerelda finally reached Callville in October 1866, after a difficult three-month journey. However, the company soon faced financial trouble, and in 1867, Johnson & Company bought both the Esmerelda and Nina Tilden. The Esmerelda was taken apart in 1868.

After buying out their rivals, Johnson & Company had no more competition. In 1869, the company was reorganized with new investors and became the Colorado Steam Navigation Company. With this new money, they started their own steamship line, using large ocean-going ships like the SS Newbern and later the SS Montana. These ships made monthly voyages from San Francisco to Port Isabel, Sonora, cutting travel time in half. This greatly sped up freight and passenger service.

Railroads and the End of Steamboats

The future of the Colorado Steam Navigation Company was changed by the Southern Pacific Company, a railroad company. In May 1877, the Southern Pacific railroad tracks reached the Colorado River at Yuma, Arizona. Soon after, Johnson and his partners sold their steamboat company to the railroad's holding company.

With the railroad reaching Yuma, it became the main port for river steamers. Ships no longer needed to go to Port Isabel, which was abandoned in 1878. The shipyard moved to Yuma. From 1879, steamboat trade upriver decreased because most freight was now unloaded from the railroad at places like Gila Bend and shipped north by land.

New gold discoveries in the 1890s brought some life back to the steamboat business. Mines like those in the Searchlight District and Goldroad District needed supplies and machinery, which the steamboats helped transport. The Gila and Mohave II steamboats were very busy, and a new barge, the Enterprise, had to be built.

However, this boom also brought new competition. Other companies started using gasoline-powered boats. In 1899, the Santa Ana Mining Company built a steamboat called the St. Valier. To compete, Polhamus and Mellon (who now owned the Colorado Steam Navigation Company) built a new boat called the Cochan in 1900. The old Mohave II was left to decay.

Another serious competitor appeared in 1902 when the Colorado River Transportation Company built the Searchlight, the last stern-wheel steamboat built on the lower Colorado. It quickly took away business from the Cochan.

By 1905, the Los Angeles and Salt Lake Railroad was built across southern Nevada. This railroad ended the need for steamboats at places like Quartette Landing and Eldorado Canyon. Also in 1905, the Arizona and California Railroad built a bridge across the Colorado River at Parker, Arizona. This cut off the last profitable section of the river for the Colorado Steam Navigation Company. By the end of 1905, all the steamboats were moved downriver to Yuma. Smaller gasoline-powered boats took their place, but even these were eventually replaced by trucks.

The remaining steamboats worked on irrigation projects and helped repair a break in the Alamo Canal that had created the Salton Sea. The final project, building the Laguna Dam, marked the end of steam navigation on the river. Only the Searchlight remained for a while, owned by the U.S. Reclamation Service, until it sank in 1916.

Steamboats on the Upper Colorado and Green Rivers

People also tried to use steamboats in places like Glen Canyon, on the Green River in Utah and Wyoming, and on the Grand River (now part of the Colorado River) in Utah and Colorado. Unlike the lower Colorado, railroads made most of this possible. They brought the boats or their parts and fuel to the river where they were put together and launched. These attempts were not as successful as the steamboat operations on the lower Colorado River.

Images for kids

-

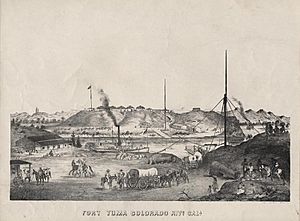

Yuma and Fort Yuma across the Colorado River (circa 1875 lithograph). Steamboat is downriver from the ferry crossing that is equipped with masts on both banks to raise the ferry's tow cables above the smokestacks of passing steamboats. Note two of the cables holding the mast up are tied to discarded boilers, presumably taken out of George A. Johnson & Company or Colorado Steam Navigation Company (C.S.N.C) steamboats when they were rebuilt or dismantled here.

-

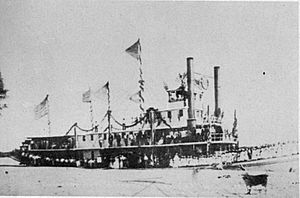

Mohave II at Yuma, Arizona, with Sunday school group embarked, 1876. Mohave, the second stern-wheel steamboat of that name running on the Colorado River for the Colorado Steam Navigation Company (C.S.N.C) between 1876 and 1900. It was the first and only double smokestack steamboat to run on the river.

-

Colorado II in a tidal dry dock in the shipyard above Port Isabel, Sonora. Colorado, the second stern-wheel steamboat of that name running on the Colorado River for the George A. Johnson & Company and Colorado Steam Navigation Company between 1862 and 1878.

-

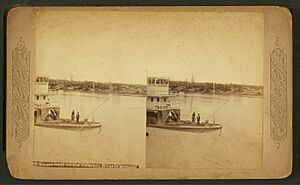

Cocopah II at Yuma, Arizona. A stereoscopic picture of the Cocopah, the second stern-wheel steamboat of that name running on the Colorado River for the Colorado Steam Navigation Company between 1867 and 1879. This photo was taken between 1877 and 1879, because the Southern Pacific railroad bridge built across the Colorado River in 1877 can be seen in the background. The railroad took away the freight business making the Cocopah obsolete and it was retired in 1879 and dismantled in 1881.

-

View showing steamboat Cochan on the Colorado River near Yuma, Arizona in 1900. A photograph of the Cochan, last stern-wheel steamboat running on the Colorado River for the Colorado Steam Navigation Company between 1899 and 1909. This photo was taken in 1900. Cochan was sold to the U.S Reclamation Service in 1909. Not required by the Service, Cochan was dismantled in 1910.

-

Remnants of the wreck of the stern-wheeler Charles H. Spencer, just below Lee's Ferry where it was abandoned in Spring 1912.

| William Lucy |

| Charles Hayes |

| Cleveland Robinson |