Aboriginal Tasmanians facts for kids

| Palawa / Pakana / Parlevar | |

|---|---|

Illustration from The Last of the Tasmanians – Woureddy, Truganini's husband

|

|

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Tasmania | 6,000–23,572 (self-identified) |

| Languages | |

|

|

| Religion | |

| Christianity; formerly Aboriginal Tasmanian religion | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Aboriginal Australians | |

The Aboriginal Tasmanians (also known as Palawa or Pakana in their language, palawa kani) are the original people of Tasmania, an island south of mainland Australia. When Europeans first arrived, there were many different Aboriginal groups living across Tasmania. For a long time in the 1900s, many people wrongly believed that the Tasmanian Aboriginal people had all died out. Today, thousands of people identify as Aboriginal Tasmanians, with numbers ranging from about 6,000 to over 23,000.

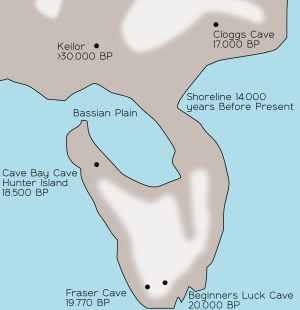

The ancestors of the Aboriginal Tasmanians first came to Tasmania about 35,000 years ago. At that time, Tasmania was connected to mainland Australia by a land bridge. Around 6000 BC, sea levels rose, cutting off Tasmania from the mainland. This meant the Aboriginal Tasmanians lived completely isolated from the rest of the world for about 8,000 years until Europeans arrived.

Before the British settled Tasmania in 1803, there were an estimated 3,000 to 15,000 Aboriginal Tasmanians. Sadly, their population dropped very quickly within just 30 years. By 1835, only about 400 people of full Tasmanian Aboriginal heritage were left. Most of these survivors were held in special camps, where many more died from illness. Historians still discuss the main reasons for this rapid decline. Some believe it was mostly due to new diseases brought by Europeans. Others point to conflicts like the Black War and other harsh treatments. Many experts today consider what happened to be a form of genocide.

In 1833, a man named George Augustus Robinson convinced about 200 remaining Aboriginal Tasmanians to surrender. He promised them protection and that their lands would be returned. However, these promises were not kept. The survivors were moved to Flinders Island and later to Oyster Cove. Diseases continued to reduce their numbers. Two important individuals, Truganini (who lived from 1812 to 1876) and Fanny Cochrane Smith (1834–1905), are remembered as some of the last people of solely Tasmanian Aboriginal descent.

Over time, all the original Tasmanian languages were lost. However, some words survived among the Palawa people, who are descendants of European men and Tasmanian Aboriginal women living on the Furneaux Islands. Today, there are efforts to reconstruct a language called Palawa kani using old word lists. Many thousands of people in Tasmania proudly identify as Aboriginal Tasmanians today, tracing their family lines back to these communities.

Contents

The History of Aboriginal Tasmanians

Life Before European Arrival

People first arrived in Tasmania about 35,000 years ago. They crossed a land bridge that connected the island to mainland Australia during the last Ice Age. When sea levels rose, this land bridge disappeared, creating the Bass Strait. This meant the Aboriginal people on the island were isolated for about 8,000 years. They had no contact with the outside world until Europeans explored the area in the late 1700s and early 1800s.

Archaeologists have found ancient sites in Tasmania that show how long Aboriginal people lived there. For example, discoveries at Kutikina Cave are 19,000 years old. In 1990, finds in Warreen Cave showed people lived there as early as 34,000 years ago. This makes Aboriginal Tasmanians the southernmost human population during the Ice Age. These discoveries provide rich evidence of early life in Greater Australia.

Early European Contact

The first European to discover Tasmania was Abel Tasman in 1642. He named it Van Diemen's Land but did not meet any Aboriginal Tasmanians.

In 1772, a French expedition led by Marion Dufresne visited Tasmania. At first, contact was friendly. However, a misunderstanding led to conflict, and French soldiers fired muskets, killing at least one Aboriginal person. Later French expeditions in 1792–93 and 1802 made peaceful contact.

The British explorer James Cook visited in 1777 and had peaceful contact with Aboriginal Tasmanians on Bruny Island. William Bligh also visited Bruny Island in 1788 and made peaceful contact.

Contact with Sealers and New Communities

More regular contact between Aboriginal Tasmanians and Europeans began in the late 1790s. British and American seal hunters started visiting the islands in Bass Strait and the coasts of Tasmania. Sealers often stayed on uninhabited islands for months. From these islands, they could reach Tasmania in small boats and meet Aboriginal people.

Trading relationships developed between sealers and Aboriginal tribes. Aboriginal people valued hunting dogs, flour, tea, and tobacco. They traded kangaroo skins for these goods. Sadly, some Aboriginal women were taken by sealers, sometimes against their will. These women were skilled at hunting seals and finding other foods. Some tribes traded their services, or women were abducted.

Many sealers were "renegade sailors, escaped convicts or ex-convicts." They settled on the Bass Strait islands and formed families with Tasmanian Aboriginal women. These relationships were sometimes forced and involved harsh treatment. For example, a woman named Tarenorerer (also known as Walyer) was taken by sealers. She later escaped and led attacks against settlers, using muskets.

Historians have recorded stories of both difficult and sometimes affectionate relationships between sealers and Aboriginal women. However, there are also many accounts of brutality. One sealer was reported to tie women to trees and whip them if they did not collect enough skins. The taking of Aboriginal women contributed to the rapid decline of the Aboriginal population in northern Tasmania. However, it also led to the formation of a mixed-race community on the Bass Strait Islands. Many modern Aboriginal Tasmanians trace their ancestry to these communities.

British Colonisation and Conflict

The first major European settlement in Tasmania began in September 1803 at Risdon Cove. This was near present-day Hobart. Early encounters between British settlers and Aboriginal clans were often hostile.

On May 3, 1804, soldiers, settlers, and convicts at Risdon Cove fired on a group of Aboriginal people. This event, known as the 1804 Risdon Cove massacre, resulted in the deaths of many Aboriginal men, women, and children. A boy whose parents were killed in this event was taken by the British and named Robert Hobart May. He became one of the first Aboriginal Tasmanians to have long-term contact with colonial society.

Between 1803 and 1823, conflicts increased. Settlers and Aboriginal people competed for food sources like kangaroos. As more white settlers arrived, some farmers and sealers also took Aboriginal women. These actions led to more conflict and a decline in the Aboriginal population.

By 1816, the kidnapping of Aboriginal children for labor was common. Governors tried to stop this practice, but it continued. Some Aboriginal children were raised in settler homes or sent to orphan schools.

Historians debate the main cause of the population decline. Some, like Geoffrey Blainey, believe introduced diseases were the biggest factor. Diseases like influenza, pneumonia, and tuberculosis spread rapidly. Aboriginal people had no natural resistance to these illnesses. Other historians, like Henry Reynolds, point to the violence of the Black War and other conflicts.

Between 1825 and 1831, Aboriginal Tasmanians began a form of guerilla warfare. As settlers expanded, native game became scarce, and Aboriginal people started raiding settler huts for food. The government's view on Aboriginal people changed. They were no longer seen as blameless. In 1828, martial law was declared against Aboriginal people. Bounties were offered for capturing those without passes, which often led to violent hunts. The Cape Grim massacre in 1828 is one example of this violence.

The Black War (1828–1832) and the Black Line (1830) were major turning points. These large campaigns against Aboriginal people, though not always successful in capturing them, made many willing to surrender to George Augustus Robinson and move to Flinders Island.

Impact of Conflict on Aboriginal and Settler Lives

This table shows the recorded impact of conflicts between Aboriginal Tasmanians and settlers. Many Aboriginal deaths were not recorded, so the actual numbers were likely higher.

| Tribe | Captured | Shot | Settlers killed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oyster Bay | 27 | 67 | 50 |

| North East | 12 | 43 | 7 |

| North | 28 | 80 | 15 |

| Big River | 31 | 43 | 60 |

| North Midlands | 23 | 38 | 26 |

| Ben Lomond | 35 | 31 | 20 |

| North West | 96 | 59 | 3 |

| South West Coast | 47 | 0 | 0 |

| South East | 14 | 1 | 2 |

| Total | 313 | 362 | 183 |

Resettlement and Challenges

In late 1831, George Augustus Robinson brought the first 51 Aboriginal people to a settlement on Flinders Island called The Lagoons. This site was not suitable, with strong winds, little water, and poor land for farming. Supplies were often insufficient, and many Aboriginal people died from disease.

They were lodged at night in shelters or "breakwinds." These "breakwinds" were thatched roofs sloping to the ground, with an opening at the top to let out the smoke, and closed at the ends, with the exception of a doorway. They were twenty feet long by ten feet wide. In each of these from twenty to thirty blacks were lodged ... To savages accustomed to sleep naked in the open air beneath the rudest shelter, the change to close and heated dwellings tended to make them susceptible, as they had never been in their wild state, to chills from atmospheric changes, and was only too well calculated to induce those severe pulmonary diseases which were destined to prove so fatal to them. The same may be said of the use of clothes ... At the settlement they were compelled to wear clothes, which they threw off when heated or when they found them troublesome, and when wetted by rain allowed them to dry on their bodies. In the case of Tasmanians, as with other wild tribes accustomed to go naked, the use of clothes had a most mischievous effect on their health.

By January 1832, more Aboriginal people arrived, leading to conflicts between different groups. A new, better camp was built at Pea Jacket Point, later renamed Wybalenna Aboriginal Establishment. Wybalenna meant "dwellings" or "black man's houses."

In 1833, Robinson persuaded 154 more Aboriginal people to move to Wybalenna. He promised them a modern life and a return to their homes. At Wybalenna, they received housing, clothing, food, medical care, and education. However, conditions were often poor, and many died from introduced diseases. Children were separated from their families. The Aboriginal people were allowed to roam the island for hunting, as food rations were often not enough.

In 1839, a government inquiry found Wybalenna to be a failure, despite Robinson's claims. In March 1847, six Aboriginal people at Wybalenna sent a petition to Queen Victoria, asking for the promises made to them to be kept. In October 1847, the 47 survivors were moved to Oyster Cove. Their numbers continued to shrink, and by 1869, only one person remained.

While Robinson and others were doing their best to make them into a civilised people, the poor blacks had given up the struggle, and were solving the difficult problem by dying. The very efforts made for their welfare only served to hasten on their inevitable doom. The white man's civilisation proved scarcely less fatal than the white man's musket.

Historical Study of Aboriginal Tasmanians

From the 1860s, the Aboriginal people at Oyster Cove attracted scientific interest from around the world. Museums wanted to collect body parts and skeletons for studies in physical anthropology. Skulls were especially sought after. Truganini feared her body would be exploited after her death. Two years after she died, her body was dug up and sent to Melbourne for study. Her skeleton was displayed in the Tasmanian Museum until 1947 and was only cremated in 1976. Another sad case was the removal of William Lanne's skull and other parts after his death in 1869.

Aboriginal people consider the removal and display of body parts to be deeply disrespectful. Their belief systems teach that a soul can only rest when laid in its homeland. Today, many institutions are returning these remains to Aboriginal communities. For example, the Royal College of Surgeons of England returned samples of Truganini's skin and hair in 2002. The British Museum returned ashes to descendants in 2007.

Modern Times: 20th Century to Today

During the 20th century, many non-Aboriginal people wrongly thought that Tasmanian Aboriginal people were extinct after Truganini's death in 1876. However, Aboriginal people continued to live and thrive. Since the 1970s, activists like Michael Mansell have worked to raise awareness and strengthen Aboriginal identity. In April 2023, UNESCO removed a document that incorrectly claimed they were extinct.

Today, there are discussions within the Tasmanian Aboriginal community about what it means to be Aboriginal. Different groups, like the Palawa and the Lia Pootah, have different views on ancestry and recognition. The Palawa are mainly descendants of sealers and Tasmanian Aboriginal women from the Bass Strait Islands. The Lia Pootah claim descent from mainland Tasmanian Aboriginal communities based on oral traditions. These discussions are important for how Aboriginal identity is recognized and supported.

The Tasmanian Palawa Aboriginal community is working hard to bring back and teach a Tasmanian language called palawa kani. They are using old records and word lists to reconstruct it. Other Tasmanian Aboriginal communities also use words from traditional languages connected to their ancestral lands.

Aboriginal Nations and Life

Aboriginal Tasmanians lived in family groups and larger social units called clans, usually with 40 to 50 people. Clans that shared a geographic area and language are now often called "nations."

Before Europeans arrived, estimates for the total Aboriginal population in Tasmania ranged from 3,000 to 15,000 people. Some studies suggest the numbers could have been much higher. Aboriginal Tasmanians were mostly nomadic, meaning they moved around. They lived in different territories based on the seasons and where they could find food. Their diet included seafood, land mammals like kangaroos and wallabies, and native plants. They socialized, married, and sometimes had conflicts with other clans.

There were more than 60 clans before European settlement. About 48 of these have been identified with specific territories. Historians like Lyndall Ryan suggest Tasmania had nine nations, each made up of six to fifteen clans. Each clan had its own defined area, and visitors needed special permission to enter.

South East Nation

The first European settlement in Tasmania, at Risdon Cove, was on the land of the South East Aboriginal people. This nation may have had up to ten clans and an estimated population of about 500 people. By 1829, only four groups, totaling around 160–200 individuals, were officially recorded. Much of their land had been taken by settlers, and their traditional food sources were greatly reduced. This region was important for mining materials like silcrete and quartzite.

The South East people sometimes had conflicts with the Oyster Bay nation to their north. Truganini belonged to the Nuenonne people of Bruny Island, which was traditionally known as Lunawanna-alonnah. Many landmarks on Bruny Island still have Nuenonne names today.

| Group | Territory | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Muwinina | Hobart area | This is the preferred contemporary name for the people of the Hobart area. |

| Nuenonne | Bruny Island | Truganini's people; traditional name for Bruny Island is Lunawanna-alonnah. |

| Melukerdee | Huon River | Associated with the lower Huon River region. |

| Lyluequonny | Recherche Bay | The southernmost recorded group. |

Aboriginal Culture

Aboriginal culture was severely disrupted in the 1800s after people lost their land and were moved to places like Wybalenna and Oyster Cove. Much traditional knowledge was lost. However, some traditions survived, especially among the Aboriginal wives of sealers on the Furneaux Islands.

Today, Aboriginal people continue to express their culture in unique ways. Their art and stories often reflect on the past, but also celebrate their strength and the ongoing life of their culture.

Pre-Colonial Traditions

We have limited information about the ceremonial and cultural life of Tasmanian Aboriginal people before Europeans arrived. Most records were written after colonization, when traditional culture had already changed greatly. Early European observers often viewed Aboriginal culture through their own cultural beliefs.

Myths and Stories

Tasmanian Aboriginal mythology was rich and likely varied among different clans. One creation story tells of two creator spirits, Moinee and Droemerdene. They were the children of Parnuen, the sun, and Vena, the moon.

Moinee was the main creator. He shaped the land and rivers of Tasmania. He also created the first man, Parlevar, from a spirit in the ground. This first man looked like a kangaroo, which is why kangaroos are important totems for Aboriginal people.

Droemerdene, who appeared as the star Canopus, helped the first men change from their kangaroo-like form. He removed their tails and shaped their knees so they could rest, making humans different from kangaroos. Moinee and Droemerdene later fought, and both fell from the sky, becoming standing stones in Tasmania.

Tasmanian Aboriginal stories also remember that the first people came by land from a distant country. This land was later flooded. This story echoes the real migration of people from mainland Australia to Tasmania when it was a peninsula, and how the land bridge disappeared after the last Ice Age.

Spiritual Beliefs

Little was recorded about traditional Tasmanian Aboriginal spiritual life. Early British settlers noted that Aboriginal people believed valleys and caves were home to spiritual beings, sometimes called "sprites." Some clans also showed respect for certain tree species in their areas.

George Augustus Robinson recorded discussions about spiritual beings that his Aboriginal companions described. These beings were sometimes called "devils" and were believed to walk alongside people, carrying a torch but remaining unseen. The leader Mannarlargenna spoke of consulting his "devil," which seemed to be a personal spiritual guide.

A powerful malevolent spirit called rageowrapper was also believed to exist. This spirit appeared as a large black man and was linked to darkness. Rageowrapper could bring strong winds or severe illness.

Some researchers believe there was a balance of "good" and "bad" spirits, linked to day and night. A creator spirit called tiggana marrabona (meaning "twilight man") was also mentioned.

Funeral Customs

Depending on clan customs, the dead might be cremated or buried in hollow trees or rock graves. Aboriginal people also sometimes kept bones of deceased relatives as talismans or amulets. These bones might be worn around the neck or kept in a kangaroo skin bag.

Cosmology

Traditional Aboriginal Tasmanians saw the night sky as home to creator spirits. They also described constellations that represented parts of tribal life, such as figures of fighting men and courting couples.

Material Culture

Using Fire

Tasmanian Aboriginal people were skilled at using fire. They wrapped coals in bark to keep them burning in Tasmania's wet climate. If their fire went out, they would ask for coals from neighbors or use friction methods to start a new fire. They used fire for cooking, warmth, hardening tools, and managing the land. They would burn vegetation to encourage and control herds of kangaroos and wallabies. This land management may have helped create the buttongrass plains in southwest Tasmania.

Hunting and Food

About 4,000 years ago, Aboriginal Tasmanians changed their diet. They started eating fewer scaled fish and more land mammals like possums, kangaroos, and wallabies. They also switched from bone tools to more efficient sharpened stone tools. Historians discuss why these changes happened. Some believe it was because large areas of scrub turned into grasslands, providing more land animals for food. Fish were never a huge part of their diet, ranking behind shellfish and seals.

Basket Making

Basket making is a traditional craft that continues today. Baskets were used for many things, including carrying food, tools, shells, and ochre. They were made from plant materials, kelp, or animal skin. Kelp baskets were especially good for carrying and serving water.

Plants like white flag iris, blue flax lily, rush, and sag were carefully chosen for their strong fibers. Modern basket makers still use these plants, sometimes adding shells for decoration.

Shell Necklace Art

Making necklaces from shells is a very important cultural tradition for Tasmanian Aboriginal women. These necklaces were used for decoration, as gifts, and for trading. This tradition dates back at least 2,600 years. It is one of the few Palawa traditions that has continued without interruption since before European settlement. Many shell necklaces are kept in the National Museum of Australia.

The necklaces were originally made from the shells of the Phasianotrochus irisodontes snail, also known as rainbow kelp shells or maireener shells. There are other types of maireener shells found in Tasmanian waters. In recent years, the number of shells has declined. This is due to the decrease in kelp and seaweed growth around Flinders Island and other areas, caused by climate change.

Ochre

Ochre is very important in Tasmanian Aboriginal culture. It comes in colors from white to yellow to red. Ochre was used for ceremonial body marking, coloring wood crafts, and other arts.

Traditionally, Aboriginal women were the only ones who collected ochre. Many Tasmanian Aboriginal men still respect this custom today. While ochre is found throughout Tasmania, the most famous source is Toolumbunner in the Gog Range. This was also a significant site for tribal meetings and trading.

Ceremonies

Early settlers described various traditional ceremonies. One was called "corroboree" (a mainland Aboriginal word adopted by settlers). These ceremonial dances and songs told traditional stories and also depicted recent events.

For example, Robinson described a "horse-dance" that showed a horseman hunting an Aboriginal person. He also mentioned a "devil-dance" performed by women from the Furneaux islands. Battles and funerals were also times for painting the body with ochre or black paint.

Visual Art

Colonial settlers recorded examples of pictorial art drawn inside huts or on paper. These designs often featured circular or spiral shapes, representing celestial bodies or clan members. Robinson noted one design that was very accurately drawn, possibly using a wooden compass.

The most lasting art form left by ancient Tasmanians are petroglyphs, or rock art. The most detailed site is at Preminghana on the West Coast. Other important sites are at the Bluff in Devonport and Greenes Creek. Hand stencils and ochre smears have been found in caves in Tasmania's Southwest, with the oldest dating back 10,000 years.

Modern Culture

Contemporary Visual Art

Today, Tasmanian Aboriginal people express their identity and culture through visual arts. Their art explores themes of loss, family, dispossession, and survival. Modern artists use textiles, sculpture, and photography. They often include ancient motifs and techniques, like shell necklaces.

Photographer Ricky Maynard's work has been shown internationally. His documentary style highlights the stories of Aboriginal people that were previously missing or misunderstood. His photographs mark important historical sites, events, and figures, speaking to their struggles in a powerful way.

Modern painting in Tasmania is also using techniques from mainland Aboriginal art. It combines these with traditional Tasmanian motifs, such as spirals and celestial images. This shows that Aboriginal art is dynamic and continues to evolve.

Shell Necklace Making Today

Tasmanian Aboriginal women have a long tradition of collecting Maireener shells to make necklaces and bracelets. This practice continues today among Aboriginal women whose families survived on the Furneaux Islands. Elder women pass down this knowledge to maintain an important link to their traditional lifestyle.

In the late 1800s, some women worked to keep this part of their culture alive for future generations. Today, only a few Tasmanian Aboriginal women continue this art. They teach their skills to younger women in their community. Shell necklace making connects them to the past and is also a modern art form.

Writing and Literature

One of the earliest publications by Tasmanian Aboriginal authors was The Aboriginal/Flinders Island Chronicle, written between 1836 and 1837.

In the past century, Tasmanian Aboriginal authors have written history, poetry, essays, and fiction. Authors like Ida West have written about their experiences growing up in white society. Phyllis Pitchford, Errol West, and Jim Everett have written poetry. Everett and Greg Lehman have explored their traditions through essays.

The Genocide Debate

There is a significant debate among historians about the rapid decline of the Aboriginal Tasmanian population. Many scholars believe that what happened qualifies as genocide.

Some historians, like Geoffrey Blainey, argue that introduced diseases were the main cause of the population collapse. Others, including Henry Reynolds, point to the violence of the Black War and other conflicts.

However, many experts in colonialism and genocide, such as Ben Kiernan and Colin Tatz, agree that the events in Tasmania fit the definition of genocide. Raphael Lemkin, who created the term "genocide," considered Tasmania a clear example. Historian Robert Hughes called it "the only true genocide in English colonial history." Many other scholars also support this view.

Official Definition of Aboriginality

In June 2005, the Tasmanian Legislative Council updated the definition of Aboriginality in the Aboriginal Lands Act. This was done to help with elections for the Aboriginal Lands Council and to clarify who is considered "Aboriginal" and eligible to vote.

Under this law, a person can claim "Tasmanian Aboriginality" if they meet three criteria:

- They have Aboriginal ancestry.

- They identify as an Aboriginal person.

- They are recognized by the Aboriginal community.

Support for the "Stolen Generations"

On August 13, 1997, the Tasmanian Parliament issued an apology for the "Stolen Generations". This refers to Aboriginal children who were forcibly removed from their families by government agencies and church missions between about 1900 and 1972.

That this house, on behalf of all Tasmanian[s] ... expresses its deep and sincere regret at the hurt and distress caused by past policies under which Aboriginal children were removed from their families and homes; apologises to the Aboriginal people for those past actions and reaffirms its support for reconciliation between all Australians.

Many people are working today in communities, universities, government, and non-profit groups to strengthen Tasmanian Aboriginal culture. They also aim to improve conditions for the descendants of these communities.

In November 2006, Tasmania became the first Australian state or territory to offer financial compensation for the Stolen Generations. The Stolen Generations of Aboriginal Children Act 2006 was passed unanimously. Up to 40 descendants of Aboriginal Tasmanians were expected to be eligible for compensation from a $5 million package.

Notable Aboriginal Tasmanians

- Eumarrah

- Kikatapula

- Maulboyheenner

- Montpelliatta

- Tongerlongeter

- Tunnerminnerwait

- Trugernanner (Truganini) and Fanny Cochrane Smith, who both claimed to be the last "full blooded" Palawa.

- William Lanne or "King Billy"

- Michael Mansell, lawyer and activist

- Mannalargenna

- Arra-Maida

- Rhyan Mansell, Australian rules footballer

- Alex Pearce, Australian rules footballer

- Derek Peardon, Australian rules footballer (first documented player in the AFL)

- Marcus Windhager, basketballer and Australian rules footballer

Literature and Entertainment

- The play The Golden Age by Louis Nowra

- The novel English Passengers by Matthew Kneale

- Historical novel Doctor Wooreddy's Prescription for Enduring the Ending of the World by Mudrooroo

- The poem Oyster Cove by Gwen Harwood

- The AFI Award-winning 1980 film Manganinnie, based on Beth Roberts' novel

- The novel The Roving party by Rohan Wilson – fictional account of Manarlagenna and William "Black Bill" Ponsonby during the Black War

- The AACTA Award-winning 2018 film The Nightingale, written, directed, and co-produced by Jennifer Kent

- The play At What Cost? by Nathan Maynard, a Belvoir St Theatre production starring Luke Carroll, premiered in Sydney in 2022, and back for another run there before touring to Brisbane, Adelaide, and Hobart in 2023.

Images for kids

-

Natives on the Ouse River, Van Diemen's Land by John Glover, 1838.

-

Horace Watson recording the songs of Fanny Cochrane Smith, considered to be the last fluent speaker of a Tasmanian language, 1903.

See also

In Spanish: Aborígenes de Tasmania para niños

In Spanish: Aborígenes de Tasmania para niños

- First Australians, TV documentary series, featuring Aboriginal Tasmanians in Episode 2

- Woretemoeteryenner (1795–1847), one of the few Palawa people to bridge the times before and after European contact