Turtle (submersible) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids History |

|

|---|---|

| Name | Turtle |

| Namesake | Turtle |

| Builder | David Bushnell |

| Laid down | 1775 |

| Launched | 1775 |

| Commissioned | 1775 |

| In service | 1775–1776 |

| Fate | Unknown |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Submersible |

| Displacement | 91 kg (201 lb) |

| Length | 3.0 m (9 ft 10 in) |

| Beam | 0.9 m (2 ft 11 in) |

| Propulsion | Hand-cranked propellers |

| Speed | 2.6 kn (4.8 km/h; 3.0 mph) |

| Endurance | 30 min |

| Notes | First submersible vessel with a documented record of use in combat |

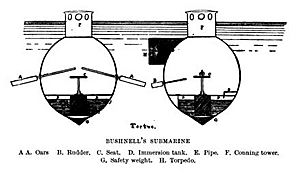

The Turtle (also called American Turtle) was the first submersible vessel ever used in a real battle. It was built in 1775 by an American named David Bushnell. Its goal was to attach explosive charges to British ships during the American Revolutionary War.

The Turtle was meant to attack Royal Navy ships in American harbors. The governor of Connecticut, Jonathan Trumbull, told George Washington about it. Washington then gave money and support to help build and test the machine.

In 1776, several attempts were made to attach explosives to British warships in New York Harbor. All of these attempts failed. Later that year, the British sank the transport ship carrying the Turtle. Bushnell said he found the machine again, but no one knows what happened to it in the end. Today, you can see modern copies of the Turtle in museums.

Contents

Building the Turtle

The American inventor David Bushnell came up with the idea for a submersible. He wanted to use it to break the British naval blockade during the American Revolutionary War. Bushnell might have started studying underwater explosions while he was at Yale University. By early 1775, he had found a way to make underwater explosives go off reliably. He used a clockwork device connected to a musket firing part.

After the Battles of Lexington and Concord in April 1775, Bushnell started building his submarine. He worked near Old Saybrook, Connecticut. It was a small vessel for one person. Its job was to attach an explosive charge to the side of an enemy ship. Bushnell wrote that it was "Constructed with Great Simplicity."

Not much is known about where Bushnell got his ideas. But it seems he knew about the work of a Dutch inventor named Cornelis Drebbel.

A doctor named Benjamin Gale, who taught at Yale, said that many of the submarine's metal parts were built by Isaac Doolittle. Doolittle was a clock-maker and metalworker in New Haven, Connecticut. Bushnell is given credit for the overall design. But Doolittle was known as a very clever engineer and metalworker. He had designed and made complex clocks and other tools. He also owned a metal foundry.

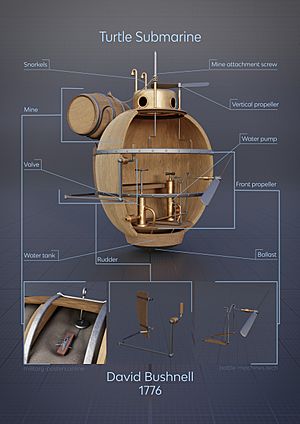

The Turtle's design was a secret. But because of Doolittle's skills, it seems he designed and made the metal parts. These included the way it moved, its navigation tools, and the pumps that let water in and out. He also made the depth gauge, compass, and the clockwork device for the mine. The hand-cranked propeller and foot-powered treadle were also likely his work.

The most important new idea in the Turtle was its propeller. It was the first time a propeller was used in a watercraft. It was described as "an oar for rowing forward or backward." It had "no precedent" design. It was also called "two oars or paddles" that were "like the arms of a windmill." These were about twelve inches (30 cm) long and four (10) wide. Since it was probably made of brass, Doolittle likely designed and made it.

For the hull, Bushnell got help from skilled workers. These included his brother Ezra Bushnell and a ship's carpenter, Phineas Pratt. Both were from Saybrook, like David Bushnell. The hull was "made of oak, like a barrel." It was held together by strong iron bands. Its shape was like "the two upper shells of a Tortoise joined together." This is how it got its name, Turtle.

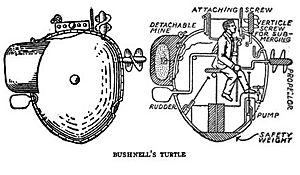

The Turtle looked like a large clam or a turtle. It was about 10 feet (3.0 m) long, 6 feet (1.8 m) tall, and 3 feet (0.9 m) wide. It had two wooden shells covered with tar and reinforced with steel bands. To dive, it let water into a tank at the bottom. To rise, it pumped water out with a hand pump. It moved up and down, and forward and backward, using hand-cranked and pedal-powered propellers. It also carried 200 pounds (91 kg) of lead. This lead could be dropped quickly to make the submarine float up.

One person operated the Turtle. It had enough air for about thirty minutes. In calm water, it could move at about 3 mph (2.6 kn; 4.8 km/h).

Six small pieces of thick glass on top let in natural light. Inside, the instruments had tiny pieces of glowing foxfire to show their position in the dark. During tests in November 1775, Bushnell found that this light stopped working when it got too cold. He asked Benjamin Franklin for other ideas, but none came. So, the Turtle was put aside for the winter.

Getting Ready for Battle

Getting money was a big worry for Bushnell while he built the Turtle. The colonies wanted to keep the submarine a secret from the British. So, records about the Turtle are often short and unclear. Most records are about Bushnell asking for money.

Bushnell met with Jonathan Trumbull, the governor of Connecticut, in 1771. He asked for money. Trumbull also sent requests to George Washington and Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson, who was an inventor, was interested. Washington was not sure about spending money from the Continental Army, which was already low on funds. But Washington did provide some money, possibly because of Trumbull.

There were problems during the design process. The mine, especially, was delayed many times. Piloting the Turtle also needed a lot of strength and skill. The operator had to control the water in the tank to keep from sinking. They also had to power the propeller with a crank and steer with a lever. The cabin only held enough air for about thirty minutes. After that, the operator had to surface to get fresh air. So, training was very important.

Bushnell did the first tests of his submarine in secret. He chose his brother, Ezra, as the pilot. Even though Bushnell wanted secrecy, news of his work reached the British quickly. A spy working for a New York politician helped spread the news.

In August 1776, Bushnell asked for volunteers to operate the Turtle. His brother Ezra, who had been the pilot, got sick. Three men were chosen. The submarine was taken to Long Island Sound for training. While they trained, the British took control of western Long Island. Since the British now controlled the harbor, the Turtle was moved overland to the Hudson River. After two weeks of training, the Turtle was taken to New York. Its new operator, Sgt. Ezra Lee, got ready to attack the main British ship, HMS Eagle.

The plan was to have Lee surface behind the Eagle's rudder. He would use a screw to attach an explosive to the ship's hull. Once it was attached, Lee would go back underwater and escape. Destroying this important British ship would hurt their morale. It might also threaten their control of New York Harbor.

The Attack on Eagle

At 11:00 pm on September 6, 1776, Sgt. Lee steered the small submarine toward Admiral Richard Howe's ship, HMS Eagle. The ship was anchored near Governors Island.

It took Lee two hours to reach the ship. It was hard work to move the hand-operated controls and foot pedals. A strong current and the dark night made it even harder to see and move.

The plan failed. Lee started with only twenty minutes of air. The darkness, strong currents, and complex controls made things very difficult. Once he surfaced, Lee lit the fuse on the explosive. He tried many times to attach the device to the bottom of the ship. But he could not pierce the Eagle's hull. He gave up the mission because the timer on the explosive was about to go off, and he feared being caught at dawn.

A popular story says he failed because the ship's hull was covered in copper. The British Navy had started adding thin copper sheets to their warships. This was to protect them from shipworms and other sea creatures. However, this copper was very thin and would not have stopped Lee from drilling through it. Bushnell thought Lee failed because of an iron plate near the ship's rudder hinge. When Lee tried another spot, he could not stay under the ship.

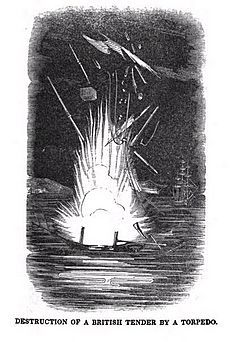

It seems more likely that Lee was tired and breathing in too much carbon dioxide. This would have made him confused and unable to drill properly. Lee said British soldiers on Governors Island saw the submarine. They rowed out to check. He then released the explosive charge, hoping they would grab it and be blown up. The British were suspicious of the floating charge and went back to the island. Lee said the charge floated into the East River. There, it exploded "with tremendous violence," throwing water and wood high into the air.

This was the first recorded time a submarine was used to attack a ship. However, only American records mention it. British records do not have any accounts of a submarine attack or explosions on the night of the supposed attack on the Eagle.

Despite the Turtle's failure, Washington called Bushnell "a Man of great Mechanical Powers, fertile of invention and a master in execution." Washington later wrote that he gave Bushnell money even though he "wanted faith myself." He added that Bushnell "never did succeed. One accident or another was always intervening." But Washington still thought it was "an effort of genius."

The Turtle's attack showed how clever American forces were after New York fell. It also showed how weaker armies often try new, sometimes radical, technologies. The submarine's final fate is unknown. But it is thought that after the British took New York, the Turtle was destroyed so it would not fall into enemy hands.

What Happened Next

On October 5, Sergeant Lee tried again to attach the charge to a frigate near Manhattan. He said the ship's watch spotted him, so he stopped the attempt. The submarine was sunk a few days later by the British. It was aboard its support vessel near Fort Lee, New Jersey. Bushnell said he found the Turtle again, but its final fate is unknown. Washington called the attempt "an effort of genius," but said "too many things were requisite" for it to succeed.

After the Turtle's attack in New York Harbor, Bushnell kept working on underwater explosives. In 1777, he designed mines to attack HMS Cerberus near New London harbor. He also tried to float mines down the Delaware River to disrupt the British fleet near Philadelphia. Both attempts failed. The Delaware River attempt was even made fun of in a poem called "Battle of the Kegs."

When the Connecticut government stopped funding underwater projects, Bushnell joined the Continental Army. He served as a captain-lieutenant of engineers and worked on the Hudson River in New York. After the war, Bushnell became less known. He visited France for several years. Then, in 1795, he moved to Georgia under a different name, David Bush. He taught school and practiced medicine there. He died in 1824, mostly unknown.

Later inventors, like Robert Fulton, were influenced by Bushnell's designs. Fulton designed his submarine Nautilus in the early 1800s. During the American Civil War, the Confederate States of America developed a working submarine, CSS H.L. Hunley. It sank the USS Housatonic in February 1864. This was the first successful submarine attack in history. By the early 1900s, navies around the world started using more submarines.

Bushnell's name is not widely known, but he is often credited with changing naval warfare. The Turtle created a way to fight from underwater that was new during the Revolutionary War. Historians say that American writers and historians in the early 1800s praised Bushnell. To a new generation of Americans, he was "the ingenious patriot who invented the submarine that terrified the British." Bushnell joined other American inventors like Eli Whitney and Robert Fulton as national heroes.

However, some historians point out that other submarine designs likely influenced Bushnell. For example, Denis Papin, a French scientist, had two submarines that might have been a model for Bushnell.

Since the Turtle was made over two centuries ago, submarine technology has spread worldwide. The United States no longer has a monopoly on it. Other navies have modernized and adopted submarine warfare. From the inventions of John Holland in the early 1900s to the German U-boats of the World Wars, and the nuclear-powered ICBM submarines of the Cold War, modern navies use submarines for many roles. Submarines are now a key part of modern navies. They go far beyond Bushnell's idea of breaking blockades. They are now essential for offensive naval warfare and showing power.

Turtle Replicas

The Turtle was the first combat submersible. It led to the modern submarine and changed underwater warfare forever. Because of this, the Turtle has been copied many times. These copies show new audiences the start of submarine technology. They also show how much it has changed and its impact on modern submarines. By the 1950s, historians called the Turtle "the greatest of the wartime inventions." The Turtle is still a source of pride, especially in Bushnell's home state of Connecticut. Its simple design has inspired at least four replicas. Many of these followed Bushnell's detailed descriptions of his submarine.

In Connecticut, the vessel was a special source of pride. In 1976, a copy of the Turtle was designed by Joseph Leary and built by Fred Frese. This was a project for the United States Bicentennial. Connecticut's governor, Ella T. Grasso, named it. It was later tested in the Connecticut River. This replica is now owned by the Connecticut River Museum.

In 2002, Rick and Laura Brown, who are sculptors from Massachusetts, built another replica. They worked with students and teachers from Massachusetts College of Art and Design. The Browns wanted to understand human cleverness better. They kept Bushnell's original design, materials, and methods. Rick Brown said, "With it, Yankee ingenuity was born." This shows how the Turtle is seen as truly American. The outer shell of this replica was carved out of a 12-foot (3.7 m) Sitka spruce log. The log was 7 feet (2.1 m) wide and came from British Columbia. This replica took twelve days to build and was successfully submerged. In 2003, it was tested in a tank at the United States Naval Academy. A professor, Lew Nuckols, made ten dives. He said, "you feel very isolated from the outside world."

In 2003, Roy Manstan, Fred Frese, and the Naval Underwater Warfare Center worked with students from Old Saybrook Senior High School in Connecticut. They started a four-year project called The Turtle Project. They built their own working replica, which they finished and launched in 2007.

On August 3, 2007, three men were stopped by police. They were piloting a Turtle replica within 200 feet (61 m) of RMS Queen Mary 2, which was docked in Red Hook, Brooklyn. The replica was made by New York artist Philip "Duke" Riley and two people from Rhode Island. One of them said he was a descendant of David Bushnell. Riley said he wanted to film himself next to the Queen Mary 2 for his art show. Riley's replica was not exact. It was 8 feet (2.4 m) tall and made of cheap plywood covered with fiberglass. Its windows and hatch came from a marine salvage company. He also put in pumps to add or remove water for balance. Riley named his vessel Acorn.

The Coast Guard gave Riley a ticket for having an unsafe vessel. He also broke the security zone around the Queen Mary 2. The NYPD also took the submarine. Police Commissioner Raymond Kelly said it was "marine mischief" and an art project, not a terrorist threat.

In 2015, the replica built by Manstan and Frese in 2007 was used in the TV series Turn: Washington's Spies. The submarine was sent to Richmond, VA. There, it was fixed up and relaunched for filming in the water. Other full-size models were also made for the show.

Also in 2015, Privateer Media used The Turtle Project replica for the Travel Channel series Follow Your Past. Filming happened in August. The submarine was launched with a rope in the Connecticut River in Essex, CT.

-

1976 working replica now at the Connecticut River Museum

-

Cutaway replica at the Submarine Force Library and Museum, Groton, Connecticut

See also

In Spanish: Tortuga (submarino) para niños

In Spanish: Tortuga (submarino) para niños

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |