White émigré facts for kids

The White émigrés were Russian people who left their home country because of big changes happening there, like the Russian Revolution and the Russian Civil War. This term is used in countries like France, the United States, and the United Kingdom. Sometimes, it describes anyone who left Russia during that time because the government changed.

Contents

A Look Back at History

In the Soviet Union (which Russia was part of from 1922 to 1991), the words White émigré had a very bad meaning between the 1920s and 1980s. After 1980, people who left Russia during this time were called first wave émigrés.

Many White émigrés believed the White movement was a good thing. Some, like the Mensheviks and Socialist-Revolutionaries, did not like the Bolsheviks (who took over Russia) but also did not support the White movement. Others simply were not interested in politics at all. A lot of those who left were still part of the Eastern Orthodox Church.

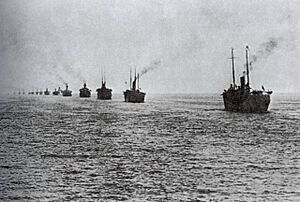

Most White émigrés left Russia between 1917 and 1920. Around 900,000 to two million people left. They came from many different groups in society. These included military soldiers and officers, Cossacks, smart people called intellectuals, businessmen, and landowners. Government officials from the time before the revolution also left.

Where Did They Go?

Most émigrés left Southern Russia and Ukraine. They first went to Turkey. From there, they moved to countries in Eastern Europe like the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, and Poland. Many also went to Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Finland, Germany, and France. Big groups of émigrés settled in Berlin and Paris.

Many regular people and military officers from Siberia and the Russian Far East moved to Shanghai and other parts of China, Central Asia, and Eastern Turkestan. Some even went to Japan.

Later, during and after World War II, many Russian émigrés moved to the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, Peru, Brazil, Argentina, and Australia.

What Did They Believe?

White émigrés generally did not like Communism. They did not think the Soviet Union was truly Russian. They believed that the time from 1917 to 1991 was like an occupation by the Soviet government. They saw this government as against traditional Russian values and Christianity.

Many White émigrés thought that Russia should be ruled by a monarch (a king or queen). Others believed that the people should choose their government through a plebiscite (a direct vote).

A key belief for many White émigrés was to keep the old Russian culture and way of life alive while living in other countries. They hoped that by doing this, they could help Russia return to its traditional culture once the Soviet Union was no longer in charge.

They also felt they had a religious mission to share Orthodoxy with the world. Bishop John of Shanghai and San Francisco, a saint of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia, once said that Russians living abroad should "shine in the whole world with the light of Orthodoxy." This meant they should do good deeds to show others that God is good and help them find salvation.

Many White émigrés also believed they should continue to fight against the Soviet government. They hoped this would help free Russia. This idea was strongly supported by General Pyotr Wrangel. After the White Army was defeated, he said, "The battle for Russia has not ceased, it has merely taken on new forms." This meant they would find new ways to try and free Russia.

Captain Vasili Orekhov, a White army veteran, wrote about this idea of responsibility. He said that in the future, when Russia is free, everyone would be asked what they did to help free it. He encouraged them to be proud of their efforts while living abroad and to keep fighting for Russia's freedom.

Groups and Activities

The émigrés created different groups to fight against the Soviet government. Examples include the Russian All-Military Union, the Brotherhood of Russian Truth, and the NTS. Because of these activities, the Soviet secret police tried to spy on and trick the White émigrés. For example, in the Spanish Civil War, 75 White army veterans volunteered to support Francisco Franco.

Some White émigrés later started to support the Soviet Union. They were called "Soviet patriots." These people formed groups like the Mladorossi and the Smenovekhovtsi.

During World War II, many White émigrés joined the Russian Liberation Movement. However, a good number also fought against the Nazis, for example, in the French Resistance. During the war, White émigrés met former Soviet citizens who had fled the Soviet Union or were in Germany as POWs and forced laborers. These people, often called the second wave of émigrés or DPs (displaced persons), preferred to stay in the West. This smaller second wave soon joined the White émigré community.

After the war, only the NTS group continued to actively fight against the Soviets. Other groups either ended or focused on keeping their culture alive and educating young people. Different youth groups, like the Russian scouts in exile, helped raise children with knowledge of pre-Soviet Russian culture and history.

To protect their church from Soviet influence, the White émigrés formed the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia in 1924. This church still exists today and serves as a spiritual and cultural center for Russians living abroad. On May 17, 2007, the church reconnected with the Russian Orthodox Church in Moscow after being separate for over 80 years.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Emigración blanca para niños

In Spanish: Emigración blanca para niños

| Jackie Robinson |

| Jack Johnson |

| Althea Gibson |

| Arthur Ashe |

| Muhammad Ali |