Yugambeh people facts for kids

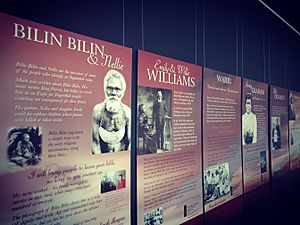

Ancestor exhibition at the Yugambeh Museum Language and Heritage Research Centre

|

|

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| ~10,000 (2016) | |

| Languages | |

| Yugambeh, English | |

| Religion | |

| Dreaming, Christianity | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Yugara, Gidhabal, Bundjalung |

| Person | Mibunn |

|---|

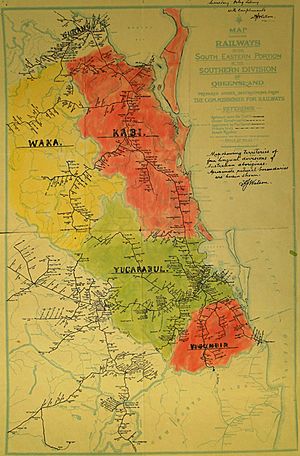

The Yugambeh people are an Aboriginal Australian group. They live in south-east Queensland and the Northern Rivers area of New South Wales. Their traditional lands are between the Logan and Tweed rivers. A term for a Yugambeh person is Mibunn, which comes from the word for the Wedge-tailed Eagle.

Archaeological finds show that Aboriginal people have lived in this area for thousands of years. When Europeans arrived, the Yugambeh had a complex system of groups and family connections. Each Yugambeh clan had its own special area with certain rights and duties. Europeans came close to their lands in the 1820s and entered around 1842. This led to Yugambeh groups being moved from their homes. Conflicts followed in the 1850s and 1860s. By the 1900s, many Yugambeh people were forced onto missions and reserves. Some found safety in the mountains or worked for Europeans. The last missions in the area closed in the late 1940s and early 1950s. From the 1970s to 1990s, Yugambeh people started groups and businesses. These focused on culture, language, housing, community care, land protection, and tourism. Before the 1850s, about 1,500 to 2,000 Aboriginal people lived in the Logan, Albert, Coomera, and Nerang river areas. The 2016 Australian census recorded over 12,000 Aboriginal people in these areas. Some of these are non-Yugambeh people who moved there for work or due to forced removals.

Contents

Understanding the Yugambeh Name

The name Yugambeh comes from their traditional language. It refers to the Aboriginal people living between the Logan and Tweed rivers. The word yugam or yugam(beh) means "no" in the Yugambeh language. Many Aboriginal groups in this area are named after their word for "no." This includes the Kabi, Wakka, Jandai, and Guwar people.

The Yugambeh language is spoken by people from the Albert and Logan River areas in South Queensland. This stretches from the Gold Coast west to Beaudesert. It also includes the coastal area of New South Wales down to the Tweed Valley. The Yugambeh people prefer to call themselves Miban or Mibiny. This word means "wedge-tailed eagle." They use Gurgun Mibinyah (Language of Mibin [Man/Eagle]) to describe their dialects.

Why "Bundjalung" Is Not Always Right

Some people, especially Europeans and nearby groups, have used the name Bundjalung for the Yugambeh. However, Yugambeh people say this name is incorrect for them. Linguists say the Aboriginal dialects from Beenleigh/Beaudesert south to the Clarence River are part of one language group. But traditionally, there was no single name for this whole language group.

The name "Bundjalung" was originally for a specific group. Over time, it became a general term after Europeans arrived. However, Aboriginal people in the Queensland part of this area never used the name Bundjalung. Northern groups, like the Yugambeh, prefer to use their own dialect names.

Other Confusing Names

Sometimes, terms like "Minyangbal" were used for more than one group. This word means "those who say minyang" (what). It was used for Yugambeh, Galibal, and Wiyabal people. It was also the self-name for the Minyungbal people at Byron Bay.

Another term, "Chepara," was used by an old anthropologist. But "Chepara" actually means "first-degree initiate" (someone who has completed the first level of a special ceremony). The person giving information might have just been saying that the group he was with were all initiates.

Yugambeh Language

The Yugambeh language is a group of related dialects. It belongs to the larger Bandjalangic branch of the Pama–Nyungan language family. In 2016, Yugambeh was officially listed as a language. The number of Yugambeh speakers grew from 18 in 2016 to 208 in 2021.

The northern dialects of Yugambeh are a distinct language group. They have many words from the Yagara language. The language varieties spoken on the Gold Coast and near the Logan River are often called the Mibin dialects. These dialects have some differences from other Bandjalang groups.

Yugambeh Dialects

The Mibiny dialects include Yugam(beh), Ngarangwal/Ngarahkwal, Nganduwal, and Minyungbal of Byron. The Yugambeh Museum says their language is spoken in the Logan, Gold Coast, Scenic Rim, and Tweed areas.

Some main dialects are:

- Yugam(beh): Also known as Yugambir or Manaldjali. This was spoken north to Jimboomba and south to the McPherson Range. It covered the Logan area to the west and Tamborine Plateau to the east.

- Ngarangwal: Spoken between the Logan River and Point Danger. It had two parts: one between the Coomera and Logan rivers, and another between the Nerang and Tweed.

- Nganduwal/Ngandowul: This dialect was spoken on the Tweed River. It was similar to the Minyung dialect spoken at Byron Bay.

Yugambeh Country

The Yugambeh traditional lands are between the Logan and Tweed Rivers. Their territory covers about 3,100 square kilometers. It stretches along the Logan River from Rathdowney to its mouth. It goes south near Southport. Their western border was around Boonah and the Great Dividing Range.

To their west and north are the Yuggera. The Quandamooka are to their north-east, on North Stradbroke and Moreton Island. The Githabul are to their south-west, and the Bundjalung are to their south.

Yugambeh Society and Culture

The Yugambeh people have strong cultural ties. They share many customs with their northern neighbours, the Yagara-speaking groups. Some differences between them and southern Bundjalung groups include:

- Different names for social groups.

- Different family systems (kinship), though some terms are shared.

- Different patterns of body scarring.

Social Divisions

In 1906, researcher R. H. Mathews learned about the Yugambeh's four social divisions. Each division was linked to specific animals, plants, and stars. This system was also used by the nearby Gidabal and Yagara people.

| Mother | Father | Son | Daughter |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baranggan | Deroin | Bandjur | Bandjuran |

| Bandjuran | Banda | Barang | Baranggan |

| Deroingan | Barang | Banda | Bandagan |

| Bandagan | Bandjur | Deroin | Deroingan |

Family Connections (Kinship)

The Yugambeh have a special family system called a "classificatory" system. This means that all members of the same social division are considered like siblings. They cannot marry each other. Family terms extend beyond blood relatives to include everyone in that relative's social division. For example, a woman from your mother's social division is considered your mother's sister, and therefore also your "mother."

In the Yugambeh system, your mother's sisters are called Waijang ("mother"). Your father's brothers are called Biyang ("father"). They would call you muyum/muyumgan ("son/daughter"). A mother's brother is called Gawang, and a father's sister is called Ngaruny. The relationship with a Ngaruny (father's sister) is very important for finding suitable marriage partners.

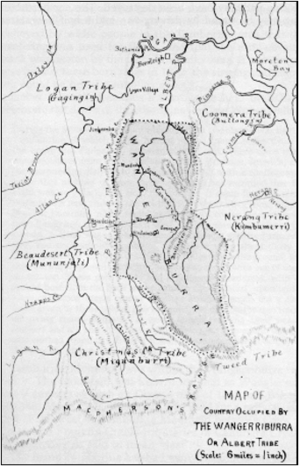

Yugambeh Clans

Like their northern neighbours, the Yugambeh are divided into several subgroups called clans. Each clan had its own special area of land. The name of each area often came from a feature of the land, like its geography, plants, or animals.

Family groups usually did not enter other Yugambeh clan areas without a good reason. Clans would visit each other for ceremonies, to settle disagreements, trade resources, or when food was scarce. They followed strict rules for visiting and using other clans' lands. Each clan also had special duties in their own country. These duties included making sure food and medicine plants grew well. They also ensured there was plenty of fish and other animals.

Clan boundaries often followed natural features like rivers and mountains. Each clan had several permanent camps they used throughout the year. For daily life, clans often split into smaller family groups. They would come together for yearly celebrations, which were also times for trading between clans.

Here are some of the Yugambeh clans:

| Name | Location | Alternative names |

|---|---|---|

| Gugingin Northerners |

Lower Logan River, lower Albert River. | Logan tribe, Guwangin, Warrilcum |

| Wanggeriburra Whiptail wallaby people. |

Middle Albert River basin and Coomera River headwaters. | Tamborine tribe |

| Bullongin River people |

Coomera River basin | Balunjali |

| Tulgigin Dry-Forest People |

Northern Lower-Tweed River basin. | Chabooburri |

| Kombumerri Mudgrove-worm People. |

Nerang River basin. | Talgaiburra |

| Mununjali Hard/baked black ground People. |

Beaudesert. | Manaldjali. |

| Murangbara Water-Vine People |

Upper-Tweed River basin. | Moorung-Mooburra |

| Kudjangbara Red-Ochre People |

Southern Lower-Tweed River Basin. | Cudgenburra, Coodjinburra. Goodjinburra |

| Migunberri Mountain Spike People |

Christmas Creek. | Migani, Balgaburri |

Yugambeh History

Life Before Europeans (Before 1824)

Aboriginal people have lived in the Gold Coast area for tens of thousands of years. When Europeans first arrived, they found many Yugambeh family groups speaking different dialects. There were nine main clan groups. These clans were exogamous, meaning men found wives from a different clan.

Yugambeh people camped by rivers and along the coast where there was plenty of food. They used various tools, including canoes. Each Yugambeh clan had its own hunting and living area. Clans often visited each other for different reasons. They also had special duties in their lands, like caring for food sources and sacred sites called djurebil. Waterholes were very important for resources.

Family groups had permanent camps and moved between them based on the seasons. Their movements were carefully planned, not random. The Gugingin clan from the Logan area were skilled net makers. They used fine nets to catch fish and large nets (15 meters wide) for kangaroos. When moving camps, groups would leave extra gear in small bark shelters. It was a matter of honor that these items were never stolen.

Coastal clans hunted, gathered, and fished. Some traditions say the Kombumerri clan worked with dolphins to catch fish. When they saw a group of fish, they would hit the water to alert the dolphins. The dolphins would then herd the fish towards the shore, making them easier to catch.

Early European Contact (1824–1860)

In 1824, a prison colony was set up north of the Yugambeh lands. The Brisbane area opened for free settlement in 1842. By 1853, the Yugambeh were cautious of government officials. Women and children would hide from strangers until they knew they were not government agents.

The Yugambeh faced violent attacks from the Australian native police. In the 1850s, a group of Yugambeh people were surprised and shot at by troopers at Mount Wetheren. In 1857, another attack happened on the Nerang River.

In 1860, six Yugambeh youths were taken from their camps near the Nerang River. They were sent to Rockhampton to be trained by a harsh officer named Frederick Wheeler. After seeing one trainee killed, the youths escaped. They walked about 550 kilometers back home, avoiding other Aboriginal groups. After three months, one youth climbed a tree and shouted Wollumbin! Wollumbin! (Mount Warning), knowing they were home. One of the youths, Keendahn, was so scared that he would hide in the bush for decades whenever police were near.

William E. Hanlon's family settled in the area around 1863. He said the Yugambeh were friendly. They brought fish, kangaroo tails, crabs, or honey to trade for flour, sugar, tea, or tobacco. Hanlon noted the area's rich resources. But by the 1930s, after he had been away for 50 years, he saw that the rivers and forests were gone. The land had changed greatly.

Mission Era (1860–1960)

The arrival of non-Indigenous people brought alcohol and diseases. Conflicts and land grabs for farming pushed Yugambeh groups from their traditional food sources. The government tried to help, but often failed.

The first mission in Queensland was founded in 1866 at Beenleigh. It aimed to Christianize and support Aboriginal people. In 1869, another mission was set up on the Nerang River. It was meant to be an "Industrial Mission" to help the Yugambeh. However, it was not successful and closed in 1879. The Beenleigh mission also closed in 1881 due to financial problems.

The Deebing Creek Aboriginal Mission started in 1887. Many different tribes were brought there. The Chief Protector of Aborigines, Archibald Meston, hoped they would live peacefully together. As settlers took more land, Yugambeh people were forced onto these reserves. Many Yugambeh stayed on their traditional lands and found work with farmers, timber cutters, and in industries like sugar and arrowroot.

Yugambeh people protested being removed from their lands. But their arguments were not accepted, and groups were sent to central reserves. The Aborigines Protection Act of 1897 led to many Yugambeh people being moved to missions and reserves across Queensland. Some, like Bilin Bilin, resisted moving until old age forced him to the Deebing Creek Mission. This mission had a school and huts and operated until 1948.

Some Yugambeh found safety in the mountains. Others worked on farms, in timber, or as domestic helpers. On the coast, some worked in fishing, oyster farming, and tourism. During both World Wars, Yugambeh people tried to join the armed forces. Their efforts were often refused due to policies against Aboriginal people. However, 10 Yugambeh people served in World War I and 47 in World War II. They have fought in every major conflict since World War I. Their contributions were often not recognized, and they were not paid the same as other soldiers.

Some Yugambeh people found refuge on Ukerebagh Island at the mouth of the Tweed River. This isolated place helped them keep their culture alive. By the early 1920s, a small community grew there. Neville Bonner, Australia's first Indigenous member of parliament, was born on Ukerebagh in 1922. In 1927, the island became an Aboriginal Reserve, providing government support. Its reserve status was removed in 1951, but families continued to live there.

Recent History (Since 1960)

From 1968 to 1983, linguists studied Yugambeh people living in Beaudesert, Woodenbong, and the Tweed. In 1974, members of the Mununjali clan started a cooperative society in Beaudesert. In the late 1970s, families on Ukerebagh Island protested against development. In 1980, the area became the Ukerebagh Island Nature Reserve.

In the early 1980s, Yugambeh people founded the Kombumerri Aboriginal Corporation for Culture. This group became very successful in preserving Aboriginal language and culture in south-east Queensland. In 1991, the Yugambeh, with help from the Gold Coast City Council, put up a War Memorial at Jebribillum Bora Park in Burleigh Heads. The memorial has a stone from Mt Tamborine, a sacred Yugambeh site. Its inscription means "Many Eagles (Yugambeh warriors) Protecting Our Country."

The Kombumerri corporation also started the Yugambeh Museum, Language and Heritage Research Centre in Beenleigh. It opened in 1995, opened by Senator Neville Bonner. The museum is a key place for learning about Yugambeh history, culture, and language. It holds educational programs, exhibitions, and traditional ceremonies.

The Gold Coast Aboriginal and Islander Housing Co-operative started in 1981. It aimed to provide affordable housing for Aboriginal people. This group later became Kalwun Development Corporation in 1994. Kalwun runs the Jellurgal Aboriginal Cultural Centre, which offers tours of the Gold Coast.

In 1998, the Ngarangwal Land Council bought land at the base of Tamborine Mountain. This land became the Guanaba Indigenous Protected Area in 2000. It covers 100 hectares of rainforest, woodlands, and creeks. This area is important for protecting endangered animals like the Fleay's barred frog and Long-nosed potoroo. The Yugambeh train young people in traditional ways at Guanaba. They also work with experts to protect the area.

The Minjungbal Aboriginal Cultural Centre is run by the Tweed Aboriginal community. It is a popular meeting place for Aboriginal people. It is built next to a Bora Ring, a sacred ceremonial site. The center has videos, art, and traditional dance. Aboriginal tour guides explain the site's history, plants, and animals.

Before the 2018 Commonwealth Games, the Yugambeh people worked with the Games organizers. They formed a Yugambeh Elders Advisory Group. A Reconciliation Action Plan was created for the Games, the first for an international sporting event. The Games mascot was named Borobi, which means "Koala" in Yugambeh language. This was the first Australian sporting mascot with an Indigenous name.

Yugambeh elders Patricia O'Connor and Ted Williams launched the Queen's Baton Relay in London. This was the first time Traditional Owners attended the ceremony. The Queen's Baton included native macadamia wood, called gumburra in Yugambeh. The design was inspired by Patricia O'Connor's story about her grandmother planting macadamia nuts along travel routes. This symbolized traditional sustainable practices.

Yugambeh Economy

The traditional Yugambeh economy was well-planned. They aimed to use resources fully. This involved following a yearly cycle based on seasonal changes. They also traded with other clans. Tools were made from local materials.

Traditional Foods (Cuisine)

The Yugambeh ate plants and animals native to their region. They ate almost anything edible, but avoided certain species for cultural reasons. A main food source was the Gulmorhan (fern-root), a starchy plant. Other plant roots, fruits, and berries were also eaten. Seeds from wattles were ground into flour. Banksia flowers were mixed with water to make a sweet drink. David's Heart leaves were used as serving plates.

They used conical fishing nets and large nets (15m wide) for kangaroos. A common cooking method was placing food on hot earth after a fire had burned out. This was used for shellfish. Larger foods like meat were cooked over a burning fire or in an earth oven. Birds, especially emus, were cooked this way.

Clans gathered on the coast for the annual autumn/winter mullet run. They also traveled to the biennial bunya nut feasts in the Bunya Mountains. Other foods included freshwater mullet, turtles, and eels. Brush Turkey eggs were highly valued. Ducks were hunted using boomerangs to scare them into nets. They also caught teredo worms by felling Swamp Oaks into estuaries to attract them.

Traditional Medicine

Yugambeh people used many plants for medicine. They still use them today. Animal parts, like fat from the Lace Monitor, were rubbed on the body. Clay was used for internal issues.

The inner bark of some trees was used for skin problems. Bark from Moreton Bay Ash was used for dysentery. Gum from Bloodwood trees treated ringworm. Spotted Gum resin helped with toothaches. Insect bites were treated with sap from Bungwall or Bracken. Milky Mangrove sap treated heat ulcers. A paste from Cunjevoi was used for burns. Soap Tree leaves were used to disinfect skin.

Infusions from Water Chestnut leaves helped healing. Native Raspberry leaves treated stomach aches. Chewing Grey Mangrove leaves eased pain from marine stings. Some plants were burned for medicine. Lemon Scented Barbwire Grass smoke had an anesthetic effect. Burnt Goats-foot leaves relieved headaches. Charred Bracket Fungi was used for healing. Some plants were used as fish poisons to make fish float to the surface, making them easier to catch.

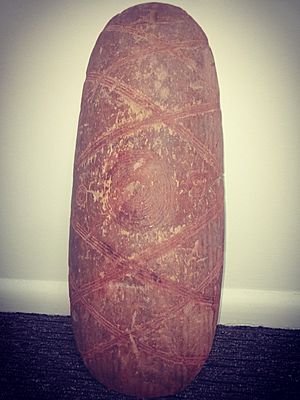

Traditional Tools (Technology)

Yugambeh technology used plants, animal parts, and natural compounds. Tree bark was used for rope. Fine strings were made from grasses. Cotton Tree bark made ropes for many uses. Kangaroo sinew fastened tools and sewed possum skins. Echidna spines were used to pierce skins.

Strong ropes made large-mesh nets for dugong and wallaby hunts. Finer ropes made fish nets. Mat rush was woven into dillybags of various sizes. Hoop pine sap was used as glue. Shelters were made from light frames covered with bark sheets and tied with rope. Native ginger leaves were used in hut making, and paperbark thatched roofs.

Weapons like spears were made from Acacia wood and hardened by fire. Boomerangs and nullahs (clubs) were made from lancewood trees. Women's digging sticks were made from hard woods like ironbark, with fire-hardened points. Shields were made from large pieces of spotted gum and grey mangrove wood.

Yugambeh Culture

Oral Traditions

The Yugambeh knew the seasonal patterns of plants and animals. They used these as signs for the time of year. Bird migrations told them when certain foods were available. For example, the lorikeet indicated the mullet season. The Pied currawong meant Black Bream were available. Flowering plants also showed when resources were ready. Hop Bush meant it was time for oysters.

Local groups used oral poems to remember this information. One poem recorded by J.A. Gresty explained when turtles and mullet were available based on the flowering of the Silky Oak and Tea Tree.

Stories, known as Bujeram (The Dreaming), held knowledge about cultural practices, beliefs, and laws. These stories connect different clan groups and form songlines. Some explain how important land features or natural events were created.

One origin story tells of three brothers, Yarberri (or Jabreen), Berruġ, Mommóm, and Yaburóng. They arrived in a canoe from an island across the sea. A woman on the land created a storm that broke their canoe, but they all swam ashore. This is how the "black race" came to this land. The pieces of the canoe are said to be certain rocks in the sea. The story also explains how different dialects came about. The brothers later separated, forming different tribes.

Another story tells of a battle between sky, land, and sea creatures at the mouth of the Logan River. This battle created many landforms and rivers in the region.

The Migunberri Yugambeh have a story about two men, Balugan and Nimbin, and their hunting dingoes, Burrajan and Ninerung. Their adventure chasing a kangaroo explains the location of many djurebil (sacred sites) and the geological features of the McPherson Range. The dingoes were eventually buried at Widgee Falls, where they turned to stone. Legend says they come alive at night and roam the Tweed Valley.

Marriage Customs

The Yugambeh believe that Yabirri (Jabreen) taught them their marriage laws. Yugambeh clans practiced exogamy, meaning people married outside their own clan. A man would visit and stay in his future wife's territory for 1-2 years. This allowed her family to judge his character and ability to provide. This custom was called Ngarabiny.

A man would marry a woman from the same social group and generation as his mother's brother's daughter. She had to be from a different part of the country and not closely related. A father's sister (Ngaruny) would often help find a suitable wife for her nephew (Nyugun/Nyugunmahn). There was a rotation in marriage, where men found wives from one direction, and women found husbands from the opposite direction.

Music and Performance

Yugambeh music used instruments like the possum skin drum (played by women), the gum leaf, and clapsticks. Early Europeans often noted the women's drumming and the use of the gum leaf as unique to the area. A large corroboree (traditional gathering) at Mudgeeraba was said to have over 600 drumming women. In the early 1900s, gum leaf bands were formed.

Yugambeh musicians also used Western instruments like the accordion (called "Ganngalmay") and guitar. Candace Kruger, a Yugambeh yarabilgingan (song woman), leads a youth choir. Their goal is to sing and learn the Yugambeh Language. The choir has performed at national and international events. Candace Kruger and others have worked with Elders to preserve the Morning Star and Evening Star Songline.

Burial Practices (Death)

Human remains were considered sacred. Burial sites were respected and kept clear. Great care was taken not to disturb old burials. If a burial was disturbed, the remains had to be treated with respect and ceremony.

Burial was a two-step process. First, the body was wrapped in paperbark and a blanket. It was then temporarily placed in a white ant's nest for a set time. After this, a family member, often the deceased's widow, would travel with the body during a period of mourning. Finally, the body was permanently buried.

On the Tweed River, bodies were buried on hillsides in a sitting position. The Migunburri buried their dead in caves and rock cracks. The Mununjali people of Beaudesert would talk to the corpse while carrying it to the grave. They would ask who caused the death. The body was said to move violently if the culprit's name was mentioned.

Native Title Claims

As of 2019, Yugambeh native title claims on their traditional lands have not been fully approved. A Kombumerri claim was filed in 1996 but was not accepted. Another claim, Kombumerri People #2, was also rejected in 1998. A larger Eastern Yugambeh People claim in 2001 was also rejected.

The Gold Coast Native Title Group (Eastern Yugambeh) claim was filed in 2006 and accepted for registration in 2013. This claim covered lands and waters in the Gold Coast area. It was dismissed in 2014 for lands that already had a lease.

The Yugambeh clans filed a new Native Title Claim in 2017 called Danggan Balun (Five Rivers) People. This claim was accepted for registration in 2017 and updated in 2020. It covers lands and waters across five local government areas in Queensland.

Notable Yugambeh People

- Ysola Best - Elder, author

- Bilin Bilin – Indigenous community leader

- Shaun Davies – Linguist, activist, media personality

- Billy Drumley – Indigenous community leader

- Jamal Fogarty – NRL player

- Lionel Fogarty - Poet

- Lambert McBride – Activist

- Lloyd McDermott – Australia's first Indigenous barrister, rugby union player

- Patricia O'Connor – Elder, language reviver

- Stephen Page – Artistic director, dancer, choreographer, film director

- David Page – Musician, composer

- Hunter Page-Lochard – Actor

- Germaine Paulson - Rugby league player

- Ellen van Neerven – Writer

- Chelsea Watego – Academic, writer

- Tony Currie - Rugby League Player

- Gary French - Rugby League Player

Images for kids

See Also

In Spanish: Pueblo yugambeh para niños

In Spanish: Pueblo yugambeh para niños

| Bessie Coleman |

| Spann Watson |

| Jill E. Brown |

| Sherman W. White |