Abul A'la Maududi facts for kids

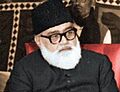

Quick facts for kids ImamAmir Allamah Shaykh al-Islam Abul A'la Maududi |

|

|---|---|

| ابو الاعلی مودودی | |

Sayyid Abul A'la Maududi

|

|

| Religion | Islam |

| Denomination | Modern Sunni |

| Lineage | Direct descendant of Islamic prophet Muhammad, through Husayn ibn Ali and Moinuddin Chishti |

| Founder of | Jamaat-e-Islami |

| Personal | |

| Born | 25 September 1903 Aurangabad, Hyderabad Deccan, British India |

| Died | 22 September 1979 (aged 75) Buffalo, New York, U.S. |

| Senior posting | |

| Title | First Amir and Imam of Jamat-e-Islami Shaykh al-Islam Allamah Sayyid Mujaddid of 20th century |

Abul A'la al-Maududi (Urdu: ابو الاعلی المودودی, romanized: Abū al-Aʿlā al-Mawdūdī; born September 25, 1903 – died September 22, 1979) was an important Islamic thinker and leader. He was active in British India and later in Pakistan. Many people see him as one of the most influential Islamic thinkers of modern times.

Maududi wrote many books and articles in Urdu. These were later translated into many languages like English, Arabic, and Bengali. He wanted to bring back what he saw as "true Islam." He believed that Islam should guide politics and that sharia (Islamic law) should be followed. He also thought it was important to keep Islamic culture strong and avoid ideas like secularism and nationalism, which he felt came from Western influences.

He started an Islamic political party called Jamaat-e-Islami. Before India was divided, Maududi and his party were against the idea of splitting India. After Pakistan was created, he worked to make it an Islamic state. His ideas greatly influenced General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq, who brought in more Islamic laws in Pakistan. Maududi received the King Faisal International Award for his service to Islam in 1979.

Contents

- Early Life and Learning

- Starting a Movement

- Maududi's Core Ideas

- Personality and Life

- Legacy and Influence

- Timeline of Abul A'la Maududi's Life

- See Also

- Images for kids

Early Life and Learning

Where Maududi Grew Up

Maududi was born in Aurangabad, a city in colonial India. He was the youngest of three sons. His father, Ahmad Hasan, was a lawyer. Maududi's family had a long history, tracing back to a famous Islamic saint named Khawajah Syed Qutb ul-Din Maudood Chishti. His mother's family also had roots in India, with ancestors who were writers and poets.

His Childhood Education

Until he was nine, Maududi was taught at home by his father and other teachers. His father wanted him to become a religious scholar, so he learned Arabic, Persian, Islamic law, and hadith (sayings and actions of Prophet Muhammad). He was a very smart child. At just 11 years old, he translated a book from Arabic into Urdu.

How He Studied

When he was eleven, Maududi joined a school that tried to mix traditional Islamic learning with modern subjects like natural sciences and philosophy. Later, he went to a more traditional Islamic school. However, his father became ill and passed away, leaving the family without money. This meant Maududi had to stop his formal schooling.

In 1919, at 16, he moved to Delhi. He taught himself English and German to study Western philosophy, sociology, and history for five years. He realized that Muslim scholars had not explored why Europe became powerful. He felt that Western thinkers had contributed much more to knowledge.

Starting as a Journalist

Maududi began his career as a journalist at 15, writing about electricity. At 17, he became an editor for an Urdu newspaper. He continued to study on his own, learning about physics and traditional Islamic subjects. He earned certificates in Islamic learning but did not call himself a formal scholar. He believed that both old and new ways of learning had their flaws.

From 1924 to 1927, Maududi edited a newspaper for a group of traditional Muslims. During this time, he started to question the Congress Party because it seemed to become more Hindu. He began to focus on Islam and believed that democracy would only work if most people in India were Muslims.

His Political Writings

Maududi wrote many important works throughout his life. His most famous and influential work is Tafhim-ul-Quran (meaning "Towards Understanding the Qur'an"). This is a six-volume translation and commentary on the Quran, which he worked on for many years, starting in 1942.

In 1932, he joined another journal and began to develop his political ideas. He started to see Islam as a complete way of life, not just a traditional religion. The government of Hyderabad even helped support his journal. Maududi was concerned about the decline of Muslim rule and the rise of secularism.

Starting a Movement

Founding Jamaat-e-Islami

In August 1941, Maududi started Jamaat-e-Islami (JI) in British India. This was a political movement aimed at promoting Islamic values. His mission was supported by other important Muslim scholars.

Jamaat-e-Islami strongly opposed the partition of India. Maududi believed that dividing India would go against the Islamic idea of the ummah (the global Muslim community). He felt that creating new borders would separate Muslims from each other.

Maududi believed that people should accept God's rule and follow divine laws, which he called a "theodemocracy." This meant that the government would be based on the entire Muslim community, not just religious scholars. After the partition, Maududi moved to Lahore, which became part of the new country of Pakistan.

After Pakistan Was Created

When India was divided in 1947, Jamaat-e-Islami also split. The part led by Maududi became Jamaat-e-Islami Pakistan.

After Pakistan was formed, Maududi became more involved in politics. Even though his party never became huge, it gained significant political influence. It played a role in protests that led to the downfall of President Muhammad Ayub Khan in 1969 and Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto in 1977.

Maududi and JI were especially influential during the early years of General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq's rule. Maududi was arrested several times because his political activities, especially his push for an Islamic state, clashed with the government. For example, in 1948, he was jailed for disagreeing with the government's actions in insurgency in Jammu and Kashmir.

In 1953, he and JI were involved in a campaign against the Ahmadiyya Community in Pakistan. This led to unrest in Lahore. Maududi was arrested and faced a severe penalty for his role in the protests. However, due to strong public support, he was released after two years. His firm stance during this time made him even more respected by his followers.

Maududi argued that an Islamic state must follow the Quran and Sunnah (Prophet Muhammad's way). He said:

An Islamic state is a Muslim state, but a Muslim state may not be an Islamic state unless and until the Constitution of the state is based on the Qur'an and Sunnah.

The campaign helped shift Pakistan's politics towards more Islamic ideas. The 1956 Constitution included many of JI's demands, which Maududi saw as a victory for Islam.

However, after a military takeover by General Ayub Khan, the constitution was set aside, and Maududi was jailed again in 1964 and 1967. In 1971, Maududi stepped back from political activism to focus on his scholarly work. In 1972, he resigned as JI's leader due to health reasons.

In 1977, Maududi became active again. When General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq took power, he respected Maududi and sought his advice. Maududi supported Zia's efforts to bring more Islamic laws to Pakistan.

Maududi's Core Ideas

Maududi put a lot of effort into writing books, pamphlets, and giving speeches. He wanted to lay the groundwork for Pakistan to become an Islamic state. He aimed to be a Mujaddid, someone who "renews" the religion. He believed a Mujaddid had a role similar to a prophet in guiding people to "true Islam."

He felt sad after the fall of the Ottoman Empire. He thought Muslims had a limited view of Islam, not seeing it as a complete way of life. He argued that to regain their strength, Muslims must accept Islam as a full guide for living.

Maududi was greatly influenced by the medieval scholar Ibn Taymiyya, who stressed God's absolute rule (Hakimiyya). Maududi believed that Jihad (struggle for God) was important for all Muslims.

What He Believed About Islam

Maududi saw the Quran not just as a religious book but as a guide for society. He believed that by following its rules, society's problems would be solved. He taught that the Quran inspires people to fight against wrongdoing and injustice.

He introduced four key ideas for understanding the Quran: ilah (divinity), rabb (lord), 'ibadah (worship, meaning complete obedience to God), and din (religion).

Maududi believed that being a Muslim meant obeying God's laws in every way. He said that "Everything in the universe is 'Muslim' for it obeys Allah by submission to His laws." This meant that stars, planets, and even atoms are "Muslims" because they follow God's rules. Only humans and jinn have free will, and only non-Muslims choose to disobey God's laws.

He taught that Islam is not just a religion in the common sense. It is a complete system that covers all parts of life:

Islam is a system encompassing all fields of living. Islam means politics, economics, legislation, science, humanism, health, psychology and sociology. It is a system which makes no discrimination on the basis of race, color, language or other external categories. Its appeal is to all mankind.

Maududi believed that a person is only truly a Muslim if their actions show their beliefs. He said that a Muslim is different from a non-believer by their knowledge and their actions based on that knowledge.

He believed that non-Muslims were struggling against truth because they denied God, even though their own nature was "Muslim" by obeying natural laws. He also thought that simply saying the shahada (declaration of faith) or being born into a Muslim family did not make someone a true Muslim.

Maududi was very interested in preserving Islamic culture, including dress, language, and customs. He wanted to protect them from what he saw as dangers like women's freedom and secularism. He believed that Islam would eventually become the "World-Religion" and solve all human problems.

However, Maududi felt that most Muslims, including many scholars, did not truly understand Islam. He believed that only a tiny percentage of Muslims knew what Islam really was. He admired the early Muslim society under Prophet Muhammad and the first four caliphs, seeing later periods as less Islamic.

Hadith and Sunnah

Maududi had unique views on hadith (sayings and actions of Prophet Muhammad). He believed that through deep study, one could develop an "intuitive sense" of what the Prophet would have said. He also thought that traditional scholars focused too much on the chain of narrators (isnad) rather than the content (matn) of the hadith.

He also wrote about the Sunnah (Prophet Muhammad's practices). He believed that any mistakes made by Prophet Muhammad mentioned in the Quran were actually God correcting even the smallest errors. He concluded that Muslims should follow every aspect of the Sunnah.

Views on Women

Irfan Ahmad noted that Maududi saw "women's visibility" in public places as a major threat to morality. He believed that art, music, films, and women using makeup were signs of wrongdoing.

Maududi taught that women's main duty was to manage the home, raise children, and provide comfort to their families. He supported the complete veiling and separation of women, meaning they should stay at home unless absolutely necessary. He believed that women should cover their faces when they left their homes.

He was against women becoming heads of state or lawmakers. He thought that active politics was not for women. However, he believed women could elect their own all-woman legislature. This body would advise the men's legislature on women's issues and could criticize general country matters, but not vote on them.

Music and Arts

Maududi saw music and dancing as harmful to society. He believed that ignoring Islamic law led to problems like poverty and people spending too much on entertainment like musicians and dancers.

Economic Ideas

Maududi's 1941 lecture on economics is considered a key text in modern Islamic economics. He believed that Islam had a complete economic system that was better than others. He called capitalism a "satanic economic system" because it encouraged saving money instead of spending it, which he thought was bad for humanity. He argued that saving too much led to overproduction and economic problems.

He also criticized socialism, saying it gave too much power to the government and could lead to people being controlled. He believed that poverty and exploitation were caused by a lack of good values among the wealthy, not by the profit motive. In an Islamic society, he thought, greed and dishonesty would be replaced by good behavior, so the government would not need to interfere much in the economy.

Maududi believed his system would be a "golden mean" between capitalism and socialism. He thought it would be superior because it would follow Islamic law, banning things like interest on loans, gambling, and fraud. However, he felt that an Islamic revolution through education was needed first to develop good values and support for Islamic law.

Banning Interest

Maududi strongly emphasized the elimination of interest on loans (riba). He believed that interest allowed moneylenders and banks to exploit the poor. He argued that the Quran strongly condemned interest.

He proposed replacing interest-based finance with "direct equity investment," where people share profits and losses. He even suggested severe penalties for repeat offenders who charged interest.

Views on Socialism

Maududi had a strong dislike for socialism, which he called "godless." He believed it was unnecessary because Islam already provided a complete system. He was a strong supporter of property rights and warned workers not to have exaggerated views of their rights, as presented by those who promoted class conflict.

He did not believe the government should guarantee employment for everyone, as this would require nationalizing all resources. He held this view despite the widespread poverty and inequality in Pakistan. He even opposed land reform proposals, arguing that Islam protected property rights. Later, he softened his views, promoting economic justice but still emphasizing the importance of private property.

Islamic Modernism

Maududi believed that Islam supported modernization but not becoming too much like the West. He agreed with Islamic Modernists that Islam was logical and superior to other religions. However, he disagreed with using human reason as the main standard for understanding the Quran and Sunnah. He believed that "true reason is Islamic" and that the Quran and Sunnah were the final authorities.

He also had a strict view on ijtihad (independent reasoning in Islamic law), limiting it to scholars with deep Islamic knowledge and faith in sharia, and only for the needs of an Islamic state.

Views on Secularism

Maududi did not see secularism as a way for governments to be neutral in multi-religious societies. Instead, he believed it removed religion from society, which he translated as "religionless." He thought this would lead to a lack of morality and ethics in society. He felt that people supported secularism to avoid moral rules and divine guidance.

Views on Science

Maududi believed that modern science was like a "body" that could hold any "spirit" or value system. He compared it to a radio that could broadcast either Islamic or Western messages.

Views on Nationalism

Maududi strongly opposed nationalism, calling it shirk (polytheism). He believed it was a Western idea that divided the Muslim world and helped Western powers stay in control. After Pakistan was formed, he and JI told Pakistanis not to pledge loyalty to the state until it became Islamic, arguing that Muslims should only be loyal to God.

Views on Traditional Scholars

Maududi also criticized traditional religious scholars (ulama) for their old-fashioned ways, their political attitudes, and their lack of knowledge about the modern world. He felt they couldn't tell the difference between the core principles of Islam and the specific rules developed over time. He believed Muslims should go back to the Quran and Sunnah, ignoring later legal judgments.

He thought that in a reformed Islamic society, the traditional role of ulama as leaders and judges would be less needed. Instead, people trained in both modern and traditional subjects would interpret Islamic law. However, as he got older, Maududi became more accepting of the ulama and sometimes worked with them.

Sufism and Popular Islam

Early in his life, Maududi was critical of Sufism (Islamic mysticism). However, his views changed as he got older. He focused his criticism on Sufi practices that were not based on sharia (Islamic law). He had studied Sufism in his youth and believed that true Sufism meant strictly following the Quran and Sunnah.

He was very critical of the worship of saints that developed in later periods. He believed that following sharia was essential for spiritual growth. Maududi argued that the highest stage of spiritual excellence could be reached through collective efforts to establish a just Islamic state, like in early Islam.

Maududi later clarified that he was not against Sufism as a whole. He distinguished between orthodox Sufism, which followed sharia (which he approved of), and popular Sufism with its shrines and rituals (which he did not). He redefined Sufism as a way to measure sincerity and good morals in religion.

Sharia (Islamic Law)

Maududi believed that sharia was not just important for being a Muslim, but that a Muslim society could not be Islamic without it. He said that if an Islamic society chose not to accept sharia, it would break its agreement with God and lose its right to be called "Islamic."

He taught that obeying God's law brought not only heavenly rewards but also blessings on Earth. Disobeying it, he believed, brought punishment and misery. The sources of sharia were the Quran and the Sunnah (Prophet Muhammad's actions and sayings).

Sharia is known for rules like banning interest on loans and specific punishments for crimes. Maududi argued that any perceived harshness of these punishments was outweighed by the problems caused by their absence in Western societies. He believed these punishments would only be applied when Muslims fully understood their faith and lived in an Islamic state.

He emphasized that sharia covered all aspects of life, including family, economy, government, and international relations. He saw it as a complete and perfect system. He also believed that a large part of sharia needed the state's power to be enforced. Therefore, in an Islamic state, the legislature's job would be to find and interpret existing laws, not to create new ones.

However, Maududi also surprisingly stated that there were many areas of human life where sharia was "totally silent," allowing an Islamic state to create its own laws. According to scholar Vali Nasr, Maududi believed sharia needed to be updated and expanded to address how a modern state functions.

Islamic Revolution

Maududi used and popularized the term "Islamic Revolution" in the 1940s. However, his idea of revolution was different from what happened in Iran or under Zia-ul-Haq. Maududi envisioned a gradual change, transforming people's hearts and minds through education and preaching (da'wah).

He spoke of Islam as a "revolutionary ideology" that aimed to rebuild society from scratch. But he was against sudden, violent, or unconstitutional actions. He believed that change should happen "step-by-step" and with "patience," because sudden changes are often short-lived.

He warned against emotional demonstrations and slogans. He thought that societies were controlled from the top down by those in power, not by movements from the general public. His revolution would be carried out by training dedicated individuals who would lead and protect the Islamic process. His party invested heavily in publishing books and articles to spread this cultural change.

Maududi was committed to non-violent politics, even if it took a century to achieve results. He stated that changing the political order through unconstitutional means was against sharia law. Even when his party faced government pressure, Maududi kept them from secret activities. It was only after he retired as leader that his party became more involved in protests.

The goal of his revolution was justice and kindness. He focused on overcoming immorality and forbidden behaviors. He was interested in ethical changes rather than social or economic ones. He believed that problems like poverty would be solved once an Islamic state was established.

The Islamic State

Maududi is credited with developing the modern idea of the "Islamic state." He explained this concept in his book, The Islamic Law and Constitution (1941).

After Pakistan was created, Maududi focused on making it an Islamic state. He imagined a state where sharia would be enforced: banks would not charge interest, sexes would be separated, hijab (veiling) would be required, and specific punishments for crimes would be carried out.

Maududi's Islamic state was based on "Islamic Democracy," and he believed it would eventually "rule the earth." He described it as a "God-worshipping democratic Caliphate." However, he stressed that Islam was more important than democracy, and the state would be judged by its loyalty to din (religion and the Islamic system).

He believed that God's rule (tawhid) meant God was the source of all law. The Islamic state would act as God's representative on Earth and enforce Islamic law. When sharia was silent on an issue, the matter would be decided by agreement among Muslims.

The state could be called a caliphate, but the "caliph" would be the entire Muslim community, a "popular vicegerency," led by an elected individual. He called this a "theodemocracy," not a "theocracy."

Maududi believed that human rule and God's rule could not exist together. He thought that human rule led to misery and injustice. Therefore, while he used the term "democracy," his "Islamic democracy" was different from Western democracy, which allows people to make laws without God's commands.

The Islamic state would make decisions through consultation (shura) among all Muslims. This consultation should be free and fair. Maududi favored giving the Islamic state the power to declare jihad and ijtihad (independent legal reasoning), which were traditionally done by religious scholars.

Rights in the Islamic State

Maududi believed that no part of life should be considered "personal and private" in an Islamic state. However, he also had a personal interest in individual rights, fair legal processes, and freedom of political expression, especially after his own experiences in jail.

He stated that spying on individuals could not be justified, even for dangerous people. He quoted the Prophet Muhammad saying that when a ruler searches for reasons for dissatisfaction, it spoils the people. However, he also believed that the basic human right in Islamic law was to demand and live in an Islamic order, not to disagree with its rulers.

The Islamic Constitution

Maududi believed that Islam had an "unwritten constitution" that needed to be written down. This constitution would be based on the practices of the "rightly guided caliphs" and the rulings of recognized legal scholars, as well as the Quran and Hadith.

Model of Government

Maududi's model for an Islamic state's government was based on Prophet Muhammad and the first four caliphs. The head of state would lead the legislature, executive, and judiciary, but these three parts would work separately. The head of state would be elected and trusted by the country, with no term limits. He also believed that anyone actively seeking a leadership position should be disqualified, as it showed greed.

He thought that because there could only be one correct view, "pluralism" (competition between political parties) would not be allowed. There would be only one party.

Maududi believed that the state would not need to govern in the Western sense because everyone would follow the same "infallible divine law." This would prevent corruption, oppression, and public unrest. Since the Prophet said, "My community will never agree on an error," there was no need for complex procedures for public consultation.

The state's legislature would consist of learned men who could interpret Quranic commands and make decisions according to sharia. Their work would be more about finding existing laws than making new ones. They would be chosen by elections or other suitable methods.

Non-Muslims or women could not be heads of state but could vote for separate lawmakers. Maududi later suggested using a referendum to resolve conflicts between the head of state and the legislature. He also allowed parties during elections but not within the legislature itself.

Initially, Maududi opposed lawyers and believed judges should implement law without discussion. But after the Pakistani judiciary helped his party, he changed his mind, supporting judicial independence and the right to appeal.

Why Western Democracy Fails

Maududi believed that Western democracy, despite its free elections, failed for two reasons. First, because it separated politics from religion, its leaders ignored morality and the common good. Second, without Islam, he felt that ordinary people could not understand their own true interests.

Non-Muslims

Maududi believed that copying the cultural practices of non-Muslims was forbidden in Islam. He thought it would weaken a nation and make it feel inferior. He strongly opposed the Ahmadiyya sect, which he and many other Muslims did not consider Muslim.

Under the Islamic State

Under Maududi's Islamic state, the rights of non-Muslims would be limited. Their faith, worship, or customs would not be interfered with, but they would have to accept Muslim rule. They would not be allowed to manage state affairs in a way that Islam considered wrong.

Non-Muslims could have "all kinds of employment" but would be kept from "key posts" in government to ensure that the state's basic policies followed Islam. They would not vote in presidential elections or for Muslim representatives. However, they might elect their own representatives to parliament, voting as separate groups. Maududi argued that Islam was the most just and tolerant system for minorities.

Non-Muslim men would also pay a special tax called jizya. This tax would exempt them from military service, which all adult Muslim men would be subject to. Those non-Muslims who served in the military would be exempt from jizya. This tax was seen as payment for protection and a symbol of Islamic rule.

Jihad (Struggle)

Maududi's early work, Al Jihad fil-Islam (1927), argued that because Islam is all-encompassing, the Islamic state should extend worldwide, not just in Muslim lands. He believed Jihad should be used to remove non-Islamic rule everywhere and establish a global Islamic state.

He taught that the destruction of lives and property during jihad was sad but necessary to prevent a greater loss, which was the victory of evil over good. He explained that jihad included not only fighting but also non-violent work to support those who were fighting.

Personality and Life

As the leader (Amir) of Jama'at e-Islami, Maududi stayed in close touch with members. He held informal discussions daily at his home. For his followers, Maududi was not just a respected scholar but a special Mujaddid (renewer of faith).

His survival of assassination attempts and the downfall of his political opponents added to his mystique. He had a powerful command of the Urdu language, which he insisted on using to free Muslims from the influence of English.

In private, he was described as strict but not rigid, quiet, composed, and firm. His biographers spoke of his special gifts and strong presence. His public speaking style was authoritative, focusing on logical arguments rather than emotional speeches. Maududi also practiced traditional medicine.

Family and Health

Maududi was close to his wife but could not spend much time with his six sons and three daughters due to his religious and political work. Only one of his children joined his party.

Maududi suffered from a kidney problem for most of his life. He was often ill and had to travel to England for treatment in 1969.

Later Years

In April 1979, Maududi's kidney problems worsened, and he also developed heart issues. He went to the United States for treatment and was hospitalized in Buffalo, New York, where his second son worked as a doctor. He passed away on September 22, 1979, at the age of 75. His funeral was held in Buffalo, but he was buried in an unmarked grave at his home in Ichhra, Lahore, after a very large funeral procession.

Legacy and Influence

Maududi is seen by many as one of the most influential contemporary Islamic revivalist scholars. His ideas have influenced Islamic movements around the world, including the Iranian revolution and the foundations of Al-Qaeda.

In Pakistan and South Asia

In Pakistan, Maududi's ideas have been very important in shaping the country's move towards his vision of Islam. His background as a journalist, thinker, and political leader has been compared to Indian independence leader Abul Kalam Azad.

He and his party are considered key in building support for an Islamic state in Pakistan. They are thought to have inspired General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq to introduce more Islamic laws. These laws included banning interest on loans, collecting a religious tax (Zakat), and introducing Islamic punishments. One policy proposed by Maududi, which was not in classic Islamic law, was having separate voting groups for non-Muslims (Hindus and Christians) in 1985. In return, Zia greatly strengthened Maududi's party, giving many members jobs in the government.

Maududi's work also had a huge influence across South Asia and among Muslims living in other countries, like Britain.

In the Arab World

Outside of South Asia, Maududi's writings were read by important figures like Hassan al-Banna, who founded the Muslim Brotherhood, and Sayyid Qutb. Qutb took Maududi's ideas about Islam being modern and about the need for a revolutionary Islamic movement. His ideas also influenced Abdullah Azzam, who helped revive the idea of jihad in Afghanistan.

In Iran

Maududi also had a big impact on Iran. It is said that Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini met Maududi as early as 1963 and later translated his works into Persian. Even today, Iran's revolutionary speeches often use his ideas.

In Turkey

In Turkey, Maududi's works became widely available in the mid-1960s, and he became an important figure among local Islamic groups.

Influence on Militant Islam

Maududi is considered one of the main intellectual founders of modern militant Islamic movements, second only to Sayyid Qutb. Many major radical Islamic groups have based their ideas and plans on the writings of Maududi and Sayyid Qutb. His works have also influenced the ideology of groups like the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant.

Timeline of Abul A'la Maududi's Life

- 1903 – Born in Aurangabad, Hyderabad State, colonial India

- 1918 – Started as a journalist for the Bijnore newspaper.

- 1920 – Became editor of the daily Taj in Jabalpur.

- 1921 – Learned Arabic in Delhi.

- 1921 – Appointed editor of the daily Muslim newspaper.

- 1926 – Received certificates in Islamic learning.

- 1928 – Received more certificates in Islamic learning.

- 1925 – Appointed editor of Al-jameeah, Delhi.

- 1927 – Wrote Al Jihad fil Islam.

- 1933 – Started Tarjuman-ul-Qur'an from Hyderabad.

- 1937 – Met the famous Muslim poet-philosopher, Allama Muhammad Iqbal, in Lahore.

- 1938 – Moved to Pathankot and joined the Dar ul Islam Trust Institute.

- 1941 – Founded Jamaat-e-Islami Hind in Lahore, British India; became its first leader (Amir).

- 1942 – Jamaat's headquarters moved to Pathankot.

- 1942 – Began writing his famous commentary of the Qur'an, Tafhim-ul-Quran.

- 1947 – Jamaat-e-Islami Pakistan headquarters moved to Lahore, Pakistan.

- 1948 – Campaigned for an Islamic constitution and government.

- 1948 – Jailed by the Pakistani government for his views on the Kashmir conflict.

- 1949 – Pakistani government accepted Jamaat's resolution for an Islamic constitution.

- 1950 – Released from jail.

- 1953 – Faced a severe penalty for his role in the agitation against Ahmadiyya after writing a booklet called Qadiani Problem. The penalty was later changed.

- 1958 – Jamaat-e-Islami was banned by military ruler Field Marshal Ayub Khan.

- 1964 – Sentenced to jail.

- 1964 – Released from jail.

- 1971 – Stepped back from leadership regarding the separation of East Pakistan (now Bangladesh).

- 1972 – Finished Tafhim-ul-Quran.

- 1972 – Resigned as Ameer-e-Jamaat (leader of Jamaat).

- 1978 – Published his last book, "Seerat-e-Sarwar-e-Aalam."

- 1979 – Received the King Faisal International Prize.

- 1979 – Traveled to the United States for medical treatment.

- 1979 – Died in Buffalo, United States.

- 1979 – Buried in Ichhra, Lahore.

See Also

- Islamic schools and branches

- Naeem Siddiqui

- Tehreek e Islami

- Contemporary Islamic philosophy

Images for kids

| Anna J. Cooper |

| Mary McLeod Bethune |

| Lillie Mae Bradford |