Agathis australis facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Agathis australis |

|

|---|---|

|

|

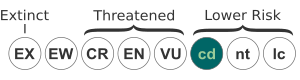

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Division: | Pinophyta |

| Class: | Pinopsida |

| Order: | Pinales |

| Family: | Araucariaceae |

| Genus: | Agathis |

| Species: |

A. australis

|

| Binomial name | |

| Agathis australis (D.Don) Loudon

|

|

|

|

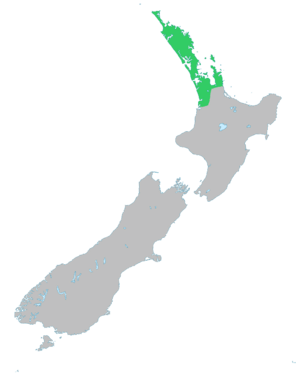

| Natural range of A. australis | |

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

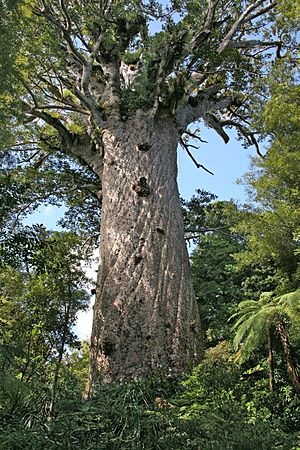

The kauri tree, also called Agathis australis, is a special type of coniferous tree. Its Māori name is kauri. It belongs to the Agathis family. You can find kauri trees in the northern parts of New Zealand's North Island, generally north of 38°S latitude.

Contents

Discover the Kauri Tree: New Zealand's Gentle Giant

The kauri is the largest tree in New Zealand by how much wood it contains. It can grow up to 50 meters tall! This makes it stand out above most other trees in the forest. Kauri trees have smooth bark and small, narrow leaves. People sometimes call it the "southern kauri" or "New Zealand kauri" to tell it apart from other trees in its family.

Kauri forests are some of the oldest forests on Earth. Kauri trees first appeared during the Jurassic period, which was about 190 to 135 million years ago. Even though they are ancient, kauri trees have a special way of living in the forest. They interact with the soil and grow in a unique pattern. This helps them compete with newer, faster-growing flowering plants. When kauri trees are present, the forest is often called a "kauri forest." These forests in warmer northern areas have many different kinds of plants. Kauri trees even change the soil under their leaves. This creates special places where only certain plants can grow.

What Does a Kauri Tree Look Like?

When a kauri tree is young, it grows straight up like a narrow cone. Its branches spread out along its trunk. But as it gets taller, the lower branches fall off. This stops vines from climbing up the tree. When a kauri tree is fully grown, its top branches form a huge crown. This crown stands tall above all other native trees, ruling the forest canopy.

The bark of the kauri tree peels off in flakes. This helps protect it from plants that might try to grow on it. The fallen bark gathers around the base of the trunk. On very large trees, this pile of bark can be more than 2 meters high! Kauri trees often grow in small groups or patches within mixed forests.

Kauri leaves are tough and leathery. They are about 3 to 7 centimeters long and 1 centimeter wide. They don't have a main vein. The leaves grow in pairs or in groups of three around the stem. The seed cones are round, about 5 to 7 centimeters across. They take 18 to 20 months to ripen after pollination. When the cones are ready, they break apart. This releases winged seeds that the wind carries away. One kauri tree produces both male and female seed cones. Fertilization happens when pollen from the same tree or another tree reaches the seeds.

How Big Can Kauri Trees Get?

Agathis australis can reach heights of 40 to 50 meters. Their trunks can be more than 5 meters wide! This makes them as wide as the giant sequoias in California. The biggest kauri trees didn't grow as tall or wide at the bottom as sequoias. But their straight, cylindrical trunks held more wood than the tapering trunks of sequoias.

The largest kauri ever recorded was called The Great Ghost. It grew in the mountains near Tararu Creek. This tree was 8.54 meters wide and 26.83 meters around! Sadly, it was destroyed by fire around 1890.

Another huge tree, Kairaru, was measured in 1860. It was 20.1 meters around. Its trunk was clear of branches for 30.5 meters. This tree was on a hill near Mount Tutamoe, about 30 kilometers south of Waipoua Forest. It was lost in the 1880s or 1890s during big fires.

Many large kauri trees were lost over time. More than 90 percent of kauri forests present before 1000 AD were destroyed by about 1900. So, it's not surprising that today's largest trees are smaller than those from the past. Even so, they are still very impressive.

Two large kauri trees fell during storms in the 1970s. One was Toronui in Waipoua Forest. It was wider than Tane Mahuta. Its clear trunk was larger than Te Matua Ngahere. Another tree, Kopi, in Omahuta Forest, was the third largest. It was 56.39 meters tall and 4.19 meters wide. It fell in 1973. Like many old kauri, both trees were partly hollow.

How Fast Do Kauri Grow and How Old Are They?

Generally, a kauri tree's growth rate increases, reaches its fastest point, then slows down. A study in 1987 found that kauri trees grew about 1.5 to 4.6 millimeters in diameter each year. The average was 2.3 millimeters per year. This means there are about 8.7 growth rings per centimeter of the tree's core. Kauri trees in planted forests grow much faster. They can produce up to 12 times more wood than trees in natural forests of the same age.

Trees of the same size can be very different ages. For example, two trees that are 10 centimeters wide might be 300 years apart in age. The biggest tree in an area is often not the oldest. Kauri trees usually live for more than 600 years. Many probably live over 1000 years. However, there is no clear proof that any kauri tree has lived for more than 2000 years. Scientists have studied tree rings from living kauri, old wooden buildings, and preserved swamp wood. This has helped them create a tree ring record that goes back 4,500 years. This is the longest tree ring record of past climate change in the Southern Hemisphere.

Kauri Roots and Soil: A Special Relationship

Kauri trees have a unique way of interacting with the soil. Like podocarps, they get their food from the organic litter near the soil surface. This layer is made of fallen leaves, branches, and dead trees. It is always breaking down. Other trees, like māhoe, get most of their food from deeper in the soil. Even though kauri's feeding roots are shallow, it also has strong "peg roots" that grow downwards. These roots anchor the huge tree firmly in the ground. This strong base stops a kauri tree from falling over in storms.

The leaves and other parts that fall from kauri trees are very acidic. As they break down, they release more acidic substances. This process is called leaching. Rainwater carries these acidic molecules through the soil layers. They wash away important nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus that are stuck in clay. This makes these nutrients unavailable to other trees. This process is called podsolization. It turns the soil a dull gray color. For a single kauri tree, this creates an area of leached soil underneath it, called a "cup podsol." This leaching process is important for kauri's survival. It helps the kauri compete with other tree species for space.

Kauri leaf litter and other decaying parts break down much slower than those from most other trees. Besides being acidic, kauri plants also have substances like waxes and phenols, especially tannins. These substances are harmful to microorganisms. This causes a large pile of litter to build up around the base of a mature tree. The kauri's own roots feed in this litter. Like most long-living plants, these feeding roots also have a symbiotic fungi called mycorrhiza. These fungi help the plant take up nutrients more efficiently. In this mutualistic relationship, the fungus gets its own food from the roots. By interacting with the soil in this way, kauri can starve its competitors of needed nutrients. This helps it compete with much younger types of plants.

Where Do Kauri Trees Grow?

Kauri trees are not found everywhere in a forest. As we learned, kauri trees survive by taking nutrients away from other plants. But the slope of the land is also important. Water flows downhill, carrying soil nutrients with it. This means soil at the top of hills has fewer nutrients, and soil at the bottom has more. Where nutrients are replaced by water flowing from above, kauri trees are less able to stop strong competitors like flowering plants from growing. But on higher ground, the leaching process works even better. In Waipoua Forest, you see more kauri trees on ridge tops. Their main competitors, like taraire, are found more often at lower elevations. This pattern is called niche partitioning. It allows different species to live in the same area. Other species that live near kauri include tawari. This is a broadleaf tree that usually grows at higher altitudes, where nutrients naturally cycle slowly.

How Kauri Distribution Changed Over Time

Today, kauri trees grow naturally north of 38°S latitude. Their southern boundary goes from the Kawhia Harbour in the west to the eastern Kaimai Range.

However, their distribution has changed a lot over geological time due to climate change. For example, during the recent Holocene epoch, kauri trees moved south after the last ice age. When large ice sheets covered much of the world, kauri could only survive in small, isolated areas. Their main safe place was in the very far north. Scientists use Radiocarbon dating to learn about the tree's history. They measure kauri stumps found in peat swamps. The coldest time recently was about 15,000 to 20,000 years ago. At that time, kauri trees were likely only found north of Kaitaia, near North Cape. Kauri needs an average temperature of 17°C or more for most of the year. The kauri's movement can tell us about temperature changes during this period.

It's not clear if kauri trees spread across the North Island from just one safe spot in the far north. Or if they came from many small groups that survived the cold. Kauri spread south through Whangārei, past Dargaville, and as far south as Waikato. They reached their widest distribution between 3000 and 2000 BP (Before Present). There are signs they have moved back north a bit since then, which might mean temperatures have dropped slightly. When they were spreading south, they moved as fast as 200 meters per year. This seems fast for a tree that can take a thousand years to fully grow. This can be explained by how they live.

Kauri trees rely on wind for pollination and seed dispersal. Many other native trees have their seeds carried far by animals that eat fruit, like the kererū (native pigeon). However, kauri trees can produce seeds when they are quite young. They can start having offspring after only about 50 years. This makes them a bit like a pioneer species. This is true even though their long lifespan is typical of K-selected species. In good conditions, with plenty of water and sunlight, kauri can grow more than 15 centimeters wide and produce seeds within 15 years.

Kauri Life Cycle and How They Grow

Kauri trees have a different way of growing and regenerating compared to their broadleaf neighbors. It's similar to how podocarp and broadleaf forests work further south. Kauri needs much more light to grow. It needs larger gaps in the forest to start new life. Broadleaf trees like puriri and kohekohe can grow in shadier places. They can grow even if only a single branch falls off a tree. Kauri trees must live long enough for a big disturbance to happen. This gives them enough light to regenerate. In areas where a lot of forest is destroyed, like by logging, kauri seedlings can grow much more easily. This is because there is more sunlight, and they are stronger against wind and frost. Kauri trees grow in the top layer of the forest, where they are exposed to the weather. But the smaller trees below are protected by the taller trees and by each other. If kauri seedlings are left in open areas without protection, they are much less likely to grow.

When a big disturbance happens that helps kauri grow, many kauri trees regenerate at once. This creates a group of trees that are all about the same age. By looking at where kauri trees grow, scientists can figure out when and where disturbances happened, and how big they were. Many kauri trees in an area might mean that the area often has disturbances. Kauri seedlings still grow in shady areas, but many of them die. Those that survive and grow into young trees are usually found in places with more light.

When there are fewer disturbances, kauri trees tend to lose ground to broadleaf trees. These competitors can handle shady environments better. If there are no disturbances at all, kauri trees become rare. They are pushed out by other species. The total amount of kauri plant material tends to decrease during these times. More plant material is found in flowering plants like towai. Kauri trees also tend to have more varied ages. Each tree dies at a different time, and new growth spots become rare. Over thousands of years, these different ways of growing create a "tug of war." Kauri moves uphill during calm times, then briefly takes over lower areas during big disturbances. We can't see these changes in one human lifetime. But research into current growth patterns, how species act in experiments, and studies of pollen (see palynology) have helped us understand the life history of kauri.

Kauri seeds can usually be collected from mature cones in late March. Each part of a cone holds one winged seed. The seed is about 5 by 8 millimeters. It has a thin wing that is about half as big again. The cone fully opens and releases its seeds within just two to three days.

Kauri trees have also been shown to connect their roots with other kauri trees. Through these root connections, they share water and nutrients with their neighbors of the same species.

Kauri and People: History and Uses

Heavy logging (cutting down trees) started around 1820 and lasted for about 100 years. This greatly reduced the number of kauri trees. Before 1840, kauri forests in northern New Zealand covered at least 12,000 square kilometers. The British Royal Navy even sent ships to gather kauri wood for masts.

By 1900, less than 10 percent of the original kauri forests were left. By the 1950s, this area had shrunk to about 1,400 square kilometers. These forests had already lost their best kauri trees. Today, it's estimated that only 4 percent of the original uncut kauri forest remains in small areas.

It's thought that about half of the kauri timber was accidentally or purposely burned. More than half of what was left was sent to Australia, Britain, and other countries. The rest was used in New Zealand to build houses and ships. Much of the timber was sold for very little money, just enough to cover costs.

The government kept selling large areas of kauri forests to sawmills. These sawmills had no rules and cut down trees in the fastest and cheapest ways. This led to a lot of waste and destruction. In 1908, over 5,000 standing kauri trees were sold for less than £2 per tree. This was a very low price for such valuable trees.

One of the most debated kauri logging decisions in the last century was in the late 1960s. The government decided to clear-cut the Warawara state forest. This forest had the second largest amount of kauri after Waipoua Forest. It had been mostly untouched until then. This decision caused a national outcry. The logging plan was very expensive. It needed a long road built up a steep plateau into the protected area. Because the kauri trees were so dense, the damage to the affected plateau area was almost complete. Logging was stopped in 1972. The public outcry over Warawara was a big step towards protecting the small amount of untouched kauri forest left in New Zealand's government-owned lands.

What Kauri Was Used For

Today, kauri wood is used much less often. But in the past, its size and strength made it popular for building and ship building. It was especially good for masts on sailing ships. This was because its grain was straight, and it had no branches for much of its height. Kauri crown and stump wood was also valued for its beauty. It was used for fancy wood panelling and high-quality furniture. Even the lighter trunk wood was good for more everyday furniture. It was also used for water tanks, barrels, bridges, fences, molds for metal, rollers for textiles, railway sleepers, and supports for mines and tunnels.

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, Kauri gum was very valuable. Kauri gum is semi-fossilized kauri resin. It was used especially for varnish. This led to an industry of gum-diggers.

Today, people are thinking about kauri as a way to store carbon for a long time. Kauri forests can hold almost 1000 tons of carbon per hectare. This is one of the highest amounts recorded for any forest type in the world. They are only beaten by mature Eucalyptus regnans forests. They hold much more carbon than most tropical or northern forests. It's also thought that kauri forests keep storing carbon without stopping. This, along with needing no direct care, makes them a good choice for carbon storage.

Kauri Timber Details

Kauri wood is considered excellent. The lighter sapwood is usually a bit lighter in weight. Kauri wood is not very resistant to rot. So, when used in boatbuilding, it must be protected with paint, varnish, or epoxy. Boatbuilders liked it because it came in very long, clear pieces. It was also relatively light and looked beautiful when oiled or varnished. The wood has a lovely shine. It is easy to plane and saw. It holds screws and nails very well. It gets a richer golden-brown color as it ages. It does not easily crack, split, or warp. Very little New Zealand kauri is sold now. The most common kauri available in New Zealand is Fiji kauri. It looks very similar but is lighter.

Swamp Kauri: Ancient Wood

Prehistoric kauri forests have been preserved in wet soils as swamp kauri. Many kauri trees have been found buried in salt marshes. This happened because of old natural changes like volcanic eruptions, sea-level changes, and floods. These trees have been radiocarbon dated to 50,000 years ago or even older. The bark and seed cones often survive with the trunk. But when they are dug up and exposed to air, these parts quickly break down. The quality of the dug-up wood varies. Some is in good condition, like newly cut kauri, but often lighter in color. The color can be improved with natural wood stains to show off the grain. After a drying process, this ancient kauri can be used for furniture, but not for building.

Protecting Kauri Trees

The small kauri forests left in New Zealand survived in areas that were not burned by Māori. They were also too hard for European loggers to reach. The largest area of mature kauri forest is Waipoua Forest in Northland. You can also find mature and growing kauri in other parks. These include Puketi and Omahuta Forests in Northland, the Waitākere Ranges near Auckland, and Coromandel Forest Park on the Coromandel Peninsula.

Waipoua Forest was very important for kauri. It was the only kauri forest that was still untouched. It was also large enough to have a good chance of surviving forever. On July 2, 1952, an area of over 80 square kilometers of Waipoua was declared a forest sanctuary. This happened after people asked the government to protect it. The zoologist William Roy McGregor was a key person in this effort. He wrote an 80-page book about it, which helped convince people to support conservation.

Along with Warawara to the North, Waipoua Forest holds three-quarters of New Zealand's remaining kauri. Kauri Grove on the Coromandel Peninsula is another area with a group of kauri trees. It includes the Siamese Kauri, which are two trees with a joined lower trunk.

In 1921, a kind man from Cornwall named James Trounson sold a large area of land to the government for £40,000. This land was next to some government land and had at least 4,000 kauri trees. Trounson also gave more land over time. Now, what is called Trounson Park covers a total of 4 square kilometers.

The most famous kauri trees are Tāne Mahuta and Te Matua Ngahere in Waipoua Forest. These two trees are popular tourist attractions because they are so big and easy to reach. Tane Mahuta, named after the Māori forest god, is the biggest living kauri. It is 13.77 meters around its trunk. Its trunk is 17.68 meters tall, and its total height is 51.2 meters. Its total volume, including the crown, is 516.7 cubic meters. Te Matua Ngahere, which means 'Father of the Forest', is smaller but wider than Tane Mahuta. It is 16.41 meters around. (Note: all these measurements were taken in 1971).

Kauri trees are often planted in parks and gardens throughout New Zealand. People like them for the unique look of young trees. Once they are established, they don't need much care, though young seedlings are sensitive to frost.

Kauri Dieback Disease

Kauri dieback disease was first seen in the Waitākere Ranges in the 1950s. It was caused by a pathogen called Phytophthora cinnamomi. Then, in 1972, it was seen on Great Barrier Island. This time, it was linked to a different pathogen, Phytophthora agathidicida. This disease later spread to kauri forests on the mainland. Kauri dieback, also known as kauri collar rot, is thought to be over 300 years old. It causes kauri leaves to turn yellow, the tree's top branches to thin out, branches to die, and sap to bleed from the trunk. Eventually, the tree dies.

Phytophthora agathidicida was identified as a new species in April 2008. Its closest known relative is Phytophthora katsurae. Scientists believe the disease spreads on people's shoes or by animals, especially wild pigs. A team has been formed to work on the disease. This team includes MAF Biosecurity, the Conservation Department, and regional councils. The team's job is to figure out the risk, find ways to stop the spread, gather more information, and make sure everyone works together. The Department of Conservation has given rules to help prevent the disease from spreading. These include staying on marked tracks, cleaning your shoes before and after entering kauri forest areas, and staying away from kauri roots.

What's in a Name?

The name Agathis comes from Greek. It means 'ball of twine'. This refers to the shape of the male cones. These are also called stroboli in botany.

Australis means 'southern'.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Kauri para niños

In Spanish: Kauri para niños

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |