Battle of Long Island facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Long Island |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Revolutionary War | |||||||

The Battle of Long Island, a 21st-century portrait of the battle |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 20,000 | 10,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 64 killed 293 wounded 31 missing |

2,179 killed, wounded or captured | ||||||

The Battle of Long Island was a major fight during the American Revolutionary War. It happened on August 27, 1776, in what is now Brooklyn, New York. In this battle, the British forces defeated the Continental Army (the American army). This victory gave the British control of the important Port of New York, which they kept for the rest of the war.

This was the first big battle after the United States declared its independence on July 4, 1776. After winning against the British in Boston in March, the American commander, George Washington, moved his army to defend New York City. Washington knew that New York's harbor would be a great base for the Royal Navy, so he set up defenses.

In July, the British, led by General William Howe, landed on Staten Island. Over the next month and a half, their army grew to 32,000 soldiers. Washington knew it would be hard to hold New York City with the British fleet controlling the harbor entrance. He moved most of his troops to Manhattan, thinking it would be the main target.

On August 21, the British landed in Gravesend Bay in Brooklyn. Five days later, they attacked American defenses on the Guan Heights. But General Howe had secretly moved his main army around the American rear and attacked their side. The Americans were surprised and lost many soldiers. About 20% were killed or captured. However, 400 soldiers from Maryland and Delaware fought bravely, preventing even greater losses. The rest of the American army retreated to their main defenses on Brooklyn Heights.

The British started preparing for a siege. But on the night of August 29–30, Washington secretly moved his entire army to Manhattan. They escaped without losing any supplies or lives. After more defeats, the Continental Army was forced to retreat from Manhattan, through New Jersey, and into Pennsylvania.

Contents

Why the Battle Happened

In the early part of the war, the British army was stuck in Boston. They had to leave on March 17, sailing to Halifax, Nova Scotia, to wait for more soldiers. General Washington then began moving his troops to New York City. He believed New York would be the next target because its port was so important.

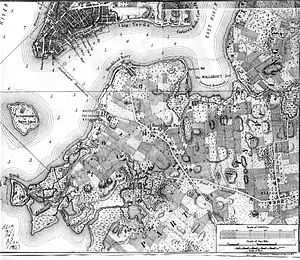

Washington sent his second-in-command, Charles Lee, to New York in February to start building defenses. When Washington arrived on April 13, the defenses were not finished. Lee had thought it would be impossible to hold the city if the British controlled the sea. So, he focused on building defenses that would make the British suffer heavy losses if they tried to take the land. They built barricades and redoubts around the city. A strong fort called Fort Stirling was built across the East River in Brooklyn Heights.

Planning the Defense

Washington started moving troops to Brooklyn in early May. Soon, thousands of soldiers were there. Three new forts were built on the eastern side of the East River to support Fort Stirling. These were Fort Putnam, Fort Greene, and Fort Box. They were connected by trenches and had 36 cannons.

Another fort, Fort Defiance, was built further southwest. Cannons were also placed at Fort George in Manhattan and at the Whitehall Dock. Old ships called hulks were sunk in waterways to stop British ships from entering.

Washington was allowed to have up to 28,501 soldiers, but he only had 19,000 in New York. Discipline was not very good. Soldiers often fired their muskets in camp, ruining their flints. They also used bayonets as knives.

Henry Knox, who led the artillery, convinced Washington to use 400 to 500 soldiers without guns to operate the cannons. In June, Knox and General Nathanael Greene decided to build Fort Washington in northern Manhattan. Fort Lee was planned across the Hudson River. These forts were meant to stop British ships from sailing up the Hudson.

British Arrive in New York

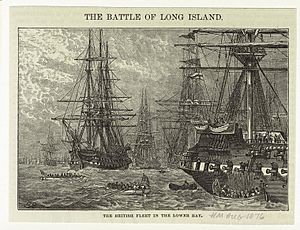

On June 28, General Washington learned that the British fleet had left Halifax and was heading to New York. On June 29, signals from Staten Island confirmed the British fleet had arrived. Within hours, 45 British ships anchored in Lower New York Bay. New Yorkers panicked, and alarms sounded.

On July 2, British troops began landing on Staten Island. American soldiers fired a few shots before running away. Many local citizens who supported the British joined them. Less than a week later, 130 ships were off Staten Island, led by Richard Howe, General Howe's brother.

On July 6, New York heard that Congress had voted for independence. On July 9, Washington had his brigades march to City Hall Park to hear the Declaration of Independence read. After the reading, a crowd tore down the statue of George III of Great Britain at Bowling Green. They cut off its head and melted the rest into musket balls.

On July 12, two British ships, Phoenix and Rose, sailed up the harbor. American cannons fired at them, but the British fired back into the city. The ships sailed up the Hudson River to Tarrytown. The British wanted to cut off American supplies and encourage Loyalists.

General Howe tried to talk with Washington. He sent a letter addressed to "George Washington, Esq." Washington's officers said he should not accept it because it did not recognize his rank as general. Washington refused the letter. Howe tried again, but Washington still refused. On July 20, Howe's officer, Colonel James Patterson, met with Washington. Patterson said Howe could offer pardons. Washington replied, "Those who have committed no fault want no pardon."

More British ships kept arriving. By August 12, 3,000 more British troops and 8,000 Hessians (German soldiers fighting for the British) had arrived. The British fleet now had over 400 ships and 32,000 soldiers on Staten Island. Washington was unsure where the British would attack. He split his army, putting half on Manhattan and half on Long Island. General Nathanael Greene commanded the troops on Long Island. But on August 20, Greene got sick, so John Sullivan took command.

The British Land on Long Island

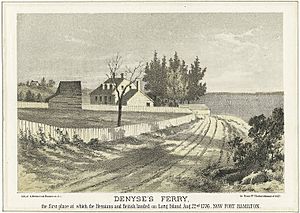

At 5:10 AM on August 22, 4,000 British troops, led by Clinton and Cornwallis, left Staten Island. They landed easily at Gravesend Bay on Long Island. American riflemen were there but did not fight. They retreated, burning farms as they went. By noon, 15,000 British soldiers and 40 cannons had landed. Many Loyalists came to welcome them. Cornwallis set up camp at Flatbush.

Washington heard about the landing but thought it was a trick. He only sent 1,500 more troops to Brooklyn, making a total of 6,000 on Long Island. On August 24, Washington replaced Sullivan with Israel Putnam to command the Long Island troops. The next day, 5,000 Hessian soldiers joined the British, bringing their total to 20,000. There were only small fights in the days after the landing.

The American plan was for Putnam to lead the defenses from Brooklyn Heights. Sullivan and Stirling would be forward on the Guan Heights. These hills were up to 150 feet high and blocked the direct path to Brooklyn Heights. Washington hoped to cause heavy British losses there before retreating. There were three main passes through the heights: Gowanus Road (west), Flatbush Road (center), and Bedford Pass (east). Stirling defended Gowanus Road with 500 men. Sullivan defended Flatbush and Bedford roads with 1,000 and 800 men. 6,000 troops stayed at Brooklyn Heights. A lesser-known path, Jamaica Pass, was guarded by only five militia officers.

General Clinton learned about the unguarded Jamaica Pass from Loyalists. He suggested a plan to Howe: the main army would march at night through Jamaica Pass to attack the American side (flank), while other troops kept the Americans busy in front. Howe agreed. On August 26, Clinton was to lead 10,000 men through Jamaica Pass. General James Grant would attack the Americans in front with 4,000 men to distract them.

The Battle Begins

The Night March

At 9:00 PM, the British army began to move. Only the commanders knew the plan. Clinton led the way with light infantry. Cornwallis followed with eight battalions and 14 cannons. Howe and Hugh Percy came next with more soldiers and supplies. The column of 10,000 men stretched for two miles. Three Loyalist farmers guided them toward Jamaica Pass. The British left their campfires burning to fool the Americans.

The British reached Howard's Tavern, near Jamaica Pass, without seeing any American troops. The tavern keeper, William Howard, and his son were forced to guide the British to an old Indian trail that went around Jamaica Pass. William Howard Jr. later described meeting General Howe. Howe told his father, "You have no alternative. If you refuse I shall shoot you through the head."

Five minutes after leaving the tavern, the five American militia officers guarding the pass were captured without a fight. They thought the British were Americans. Clinton questioned them and learned they were the only guards. By dawn, the British were through the pass. At 9:00 AM, they fired two cannons. This was the signal for the Hessian troops to attack Sullivan's men from the front, while Clinton's troops attacked from the side.

Grant's Distraction Attack

Around 11:00 PM on August 26, the first shots of the battle were fired near the Red Lion Inn. American soldiers fired at two British soldiers looking for watermelons.

Around 1:00 AM on August 27, 200–300 British troops approached the Red Lion. American troops fired at them, then ran back toward the Vechte–Cortelyou House. Major Edward Burd was captured.

General Samuel Holden Parsons and Colonel Samuel John Atlee were further north on Gowanus Road. General Putnam was woken up at 3:00 AM and told the British were attacking. He sent signals to Washington and rode to warn Stirling.

Stirling led 1,600 troops, including soldiers from Delaware and Maryland. He placed Atlee's men in an apple orchard. When the British came, the Americans fired and then retreated to a hill. Stirling positioned the Delaware and Maryland regiments on a rise of land. Some Maryland troops were on a small hill called Blokje Berg. When the British advanced, the Americans fired from behind a ditch.

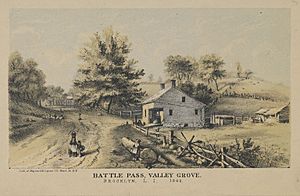

Southeast of Blokje Berg was Battle Hill, the highest point in King's County. The British tried to go around the American positions by taking this hill. The Americans fought fiercely to stop them and managed to push the British off the hill. Battle Hill saw very brutal fighting, and the Americans caused the most British casualties here. Among those killed was British Colonel James Grant. The Americans were still unaware that this was just a distraction.

Battle Pass Chaos

The Hessians, led by General von Heister, began firing cannons at the American lines at Battle Pass. They did not attack yet, waiting for the British signal. The Americans still thought Grant's attack was the main one. Sullivan sent 400 of his men to help Stirling.

Howe fired his signal guns at 9:00 AM. The Hessians attacked Battle Pass, and the main British army attacked Sullivan's men from behind. Sullivan left some soldiers to fight the Hessians and turned the rest to fight the British. Many soldiers on both sides were killed or ran away. Sullivan tried to lead a retreat, but the American left side collapsed. Hand-to-hand fighting broke out. Some Americans who surrendered were reportedly killed by Hessians. Sullivan was captured, but he managed to get most of his men back to Brooklyn Heights.

The Maryland 400

At 9:00 AM, Washington arrived from Manhattan. He realized he was wrong about the British plan. He ordered more troops from Manhattan to Brooklyn.

Stirling was still holding his line against Grant on the American right. He fought for four hours, not knowing about the British flanking move. Some of his soldiers thought they were winning. However, Grant got 2,000 more soldiers, and by 11:00 AM, he attacked Stirling's center. Stirling was also attacked by Hessians on his left. Stirling pulled back, but British troops were coming from behind him. The only way to escape was across Brouwer's millpond on the Gowanus Creek, which was 80 yards wide. The American defenses on Brooklyn Heights were on the other side.

Stirling ordered all his troops to cross the creek, except for a group of Maryland soldiers led by Gist. This group became known as the "Maryland 400", though there were about 260–270 men. Stirling and Gist led these Marylanders in a brave fight against over 2,000 British soldiers with two cannons. They attacked the British twice at the Vechte–Cortelyou House. After the last attack, the remaining troops retreated across the creek. Some got stuck in the mud under enemy fire, and others who couldn't swim were captured. Stirling was surrounded and surrendered to the Hessians. Two hundred fifty-six Maryland soldiers were killed in front of the Old Stone House. Fewer than a dozen made it back to the American lines. Washington watched from a nearby fort and reportedly said, "Good God, what brave fellows I must this day lose."

British Halt the Attack

American troops who were not killed or captured escaped behind the strong defenses at Brooklyn Heights. General Howe then ordered his troops to stop attacking. Many of his officers wanted to keep pushing to Brooklyn Heights. But Howe decided not to attack the American defenses directly. Instead, he chose to start a siege. He believed the Americans were trapped, with his troops blocking land escape and the Royal Navy controlling the East River.

Howe's decision not to attack has been debated. He might have wanted to avoid heavy losses like the British suffered at the Battle of Bunker Hill. He might also have hoped Washington would surrender. Howe later told Parliament that his main duty was to avoid losing too many British soldiers for little gain. He thought capturing Brooklyn Heights might not mean capturing the entire American army.

After the Battle

The Great Escape to Manhattan

Washington and the Continental Army were surrounded on Brooklyn Heights, with the East River behind them. The British began digging trenches, slowly getting closer to the American defenses. This meant the British would not have to cross open ground to attack, as they did in Boston. Even in this dangerous situation, Washington ordered 1,200 more men from Manhattan to Brooklyn on August 28. Two Pennsylvania regiments and Colonel John Glover's regiment from Massachusetts came to help.

As rain began to fall on the afternoon of August 28, Washington had his cannons fire at the British all night. Washington sent a letter telling General William Heath to send every flat-bottomed boat and sloop (small ship) without delay. He thought soldiers from New Jersey might come to help.

At 4:00 PM on August 29, Washington met with his generals. Thomas Mifflin suggested retreating to Manhattan. Mifflin and his Pennsylvania regiments would stay behind as a rear guard, holding the line until the rest of the army left. The generals all agreed. Washington sent out orders that evening.

The soldiers were told to gather their ammunition and bags and prepare for a night attack. By 9:00 PM, the sick and wounded began moving to the Brooklyn Ferry for evacuation. At 11:00 PM, Glover and his Massachusetts men, who were sailors and fishermen, started moving the troops across the river.

As more troops left, others were ordered to pull back from the front lines and march to the ferry. Wagon wheels were muffled, and soldiers were told not to talk. Mifflin's rear guard kept campfires burning to trick the British into thinking the Americans were still there. At 4:00 AM on August 30, Mifflin was told it was his unit's turn to leave. He was confused but eventually ordered his troops to move. When Mifflin's troops were close to the ferry, Washington rode up and asked why they weren't at their defenses. Mifflin explained he was told it was his turn. Washington told him it was a mistake. Mifflin then led his troops back to the outer defenses.

Cannons, supplies, and troops were all being moved across the river. It was slower than Washington expected, and daybreak came. But a thick fog settled in, hiding the evacuation from the British. British patrols noticed there were no American guards and started searching. As they did, Washington, the last man left, stepped onto the last boat. By 7:00 AM, all 9,000 American troops had landed safely in Manhattan, with no lives lost during the retreat.

Aftermath of the Campaign

The British were shocked to find that Washington and the Continental Army had escaped. Later that day, on August 30, British troops took over the American forts. When news of the battle reached London, there were many celebrations. King George III gave General Howe an award.

Some people thought Washington's defeat showed he wasn't a good military planner. His generals were inexperienced, and his new soldiers ran away. However, Washington's daring retreat that night is now seen by many historians as one of his greatest military achievements. Other historians focus on why the British navy failed to stop the escape.

Howe did not attack again for two weeks. On September 15, he landed troops at Kip's Bay and quickly took New York City. American troops fought back at Harlem Heights, but Howe defeated Washington again at White Plains and Fort Washington. Because of these defeats, Washington and his army retreated through New Jersey into Pennsylvania. On September 21, a fire destroyed a quarter of New York City. After the fire, Nathan Hale was executed for spying.

Casualties and Prisoners

Over 40,000 men fought in the battle, including the British navy. Howe reported his losses as 59 killed, 268 wounded, and 31 missing. The Hessians lost 5 killed and 26 wounded. The Americans suffered much more. About 300 were killed and over 1,000 were captured. Sadly, only about half of the captured soldiers survived. They were kept on prison ships in Wallabout Bay, then moved to places like the Middle Dutch Church. They were starved and did not get medical care. Many died from smallpox.

Historians believe that as many as 256 soldiers from the First Maryland Regiment died in the battle. They were buried in a mass grave, but its exact location has been a mystery for over 240 years.

What We Remember Today

The Battle of Long Island showed that the war would not be easy. It would be long and bloody. The British took control of the important harbor and kept New York City under military rule until the war ended. The city became a center for spying and gathering information. The area around the city was often in conflict as both sides looked for supplies.

Here are some ways the battle is remembered:

- The Altar to Liberty: Minerva monument: This monument has a bronze statue of Minerva on Battle Hill, the highest point in Brooklyn, in Green-Wood Cemetery. The statue was put up in 1920 and looks toward the Statue of Liberty. An annual event starts at the cemetery entrance and marches to the monument.

- The Prison Ship Martyrs' Monument: A tall column in Fort Greene remembers all the prisoners who died on British ships off the coast of Brooklyn.

- Soldiers' Monument – Milford, Connecticut: This memorial remembers 200 sick prisoners from the battle who were left on the beach at Milford on January 3, 1777.

- The Old Stone House: This rebuilt farmhouse (from around 1699) was where the Maryland soldiers fought bravely. It is now a museum about the battle in J.J. Byrne Park, Brooklyn. It has models and maps.

- Prospect Park, Brooklyn, Battle Pass: On the eastern side of East Drive, there is a large granite rock with a brass plaque. Another marker is for the Dongan Oak, a very old tree cut down to block the pass from the British. The park also has the Line of Defense marker and the Maryland Monument.

There are currently 30 units in the U.S. Army today whose history goes back to the colonial and revolutionary times.

Interesting Facts About the Battle of Long Island

- The Battle of Long Island was the largest battle of the Revolutionary War. It had the most soldiers fighting and was the biggest battle ever fought in North America at that time.

- 8,000 Hessians (German soldiers) came to help the British.

- The battle is also known as the Battle of Brooklyn or the Battle of Brooklyn Heights.

- Five Army National Guard units and one Regular Army Field Artillery battalion today are connected to American units that fought in the Battle of Long Island.

See also

In Spanish: Batalla de Long Island para niños

In Spanish: Batalla de Long Island para niños

- List of American Revolutionary War battles

- American Revolutionary War §British New York counter-offensive. This shows where the Battle of Long Island fits in the overall war.

- Dr. John Hart, a surgeon who was stationed at Governor's Island.

- Long Island order of battle

- New York and New Jersey campaign