Paul Cézanne facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Paul Cézanne

|

|

|---|---|

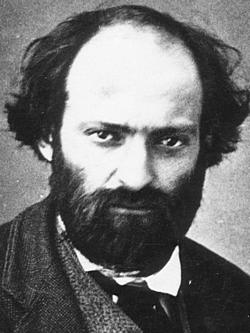

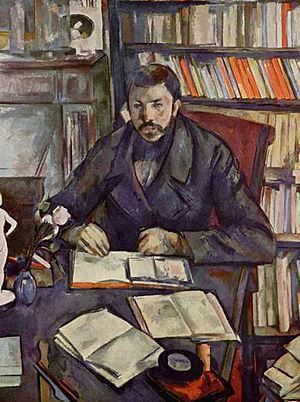

Cezanne in 1899

|

|

| Born | 19 January 1839 Aix-en-Provence, France

|

| Died | 22 October 1906 (aged 67) Aix-en-Provence, France

|

| Resting place | Saint-Pierre Cemetery |

| Nationality | French |

| Education | Académie Suisse Aix-Marseille University |

| Known for | Painting |

|

Notable work

|

Mont Sainte-Victoire (1885–1906) Apothéose de Delacroix (1890–1894) Rideau, Cruchon et Compotier (1893–94) The Card Players (1890–1895) The Bathers (1898–1905) |

| Movement | Impressionism, Post-Impressionism |

| Awards | Cézanne medal |

Paul Cézanne (19 January 1839 – 22 October 1906) was a French artist. He was a Post-Impressionist painter. His work brought new ways of showing things and influenced art movements in the early 1900s. People say Cézanne helped connect late 19th-century Impressionism with Cubism in the early 20th century.

Cézanne's early paintings were influenced by Romanticism and Realism. But he developed his own unique style by studying Impressionist ideas. He changed how artists used perspective and broke old art rules. He focused on the basic shapes of objects and the formal qualities of art. Cézanne wanted to update traditional art methods using Impressionist color ideas. His brushstrokes were often repeated and looked like he was exploring the subject. He used blocks of color and small strokes to create complex areas. His paintings show how deeply he studied his subjects. Famous artists like Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso both said that Cézanne "is the father of us all."

At first, many art critics did not understand or even made fun of his paintings. Until the late 1890s, mostly other artists like Camille Pissarro and art dealer Ambroise Vollard discovered his work. They were among the first to buy his paintings. In 1895, Vollard held Cézanne's first solo art show in his Paris gallery. This helped more people learn about the artist's work.

Contents

Life Story

Early Life and Family

Paul Cézanne was born in Aix-en-Provence, France. His father, Louis-Auguste Cézanne, was a hat maker who later became a banker. His mother was Anne-Elisabeth-Honorine Aubert. Paul was born on January 19, 1839. His parents married after Paul and his sister Marie (born 1841) were born. His youngest sister Rose was born in 1854. The Cézanne family came from Saint-Sauveur. Paul was baptized on February 22, 1839. He became a very religious Catholic later in life. His father's banking business did well, giving Paul financial security. He later received a large inheritance.

His mother, Anne Elisabeth Honorine Aubert, was lively and romantic. Cézanne got his view of life from her. He also had two younger sisters, Marie and Rose. He went to primary school with them every day.

At age ten, Cézanne went to Saint Joseph school in Aix. His classmates included Philippe Solari, who later became a sculptor. In 1852, Cézanne went to Collège Bourbon (now Collège Mignet). There, he became friends with Émile Zola and Baptistin Baille. They were known as "Les Trois Inséparables" (The Three Inseparables). This was likely a very happy time for him. The friends swam and fished, talked about art, and wrote poems. Cézanne often wrote his poems in Latin. Zola encouraged him to take poetry more seriously, but Cézanne saw it as just a hobby. He stayed at the college for six years. In 1857, he started attending the Free Municipal School of Drawing in Aix. He studied drawing there with Joseph Gibert.

His father wanted him to take over the bank. So, Paul Cézanne enrolled in law school at the University of Aix-en-Provence in 1859. He studied law for two years, but he didn't like it. He spent more time drawing and writing poems. From 1859, Cézanne took evening classes at the École de dessin d'Aix-en-Provence. His teacher was Joseph Gibert. In August 1859, he won second prize in a figure drawing class.

His father bought the Jas de Bouffan estate that same year. This old house became Cézanne's home and workplace for a long time. The house and old trees in its park were some of his favorite subjects. In 1860, Cézanne got permission to paint the walls of the living room. He created large murals of the four seasons. He jokingly signed them as Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, an artist he didn't admire.

Cézanne decided to become an artist, even though his father didn't want him to. He left Aix for Paris in 1861. Zola, who was already in Paris, strongly encouraged him. Eventually, his father accepted Cézanne's choice. He supported his art studies, as long as he studied regularly. Cézanne later inherited a lot of money from his father. This meant he never had to worry about money.

Art Studies in Paris

Cézanne moved to Paris in April 1861. He hoped to get into the École des Beaux-Arts, a famous art school, but he was rejected. He attended the free Académie Suisse instead. There, he could practice drawing from live models. He met Camille Pissarro, who was ten years older, and Achille Emperaire from his hometown. He often copied works by old masters like Michelangelo and Titian at the Louvre museum. But he didn't feel comfortable in Paris. He soon thought about going back to Aix-en-Provence. Pissarro became a mentor to Cézanne. Over the next ten years, they often painted landscapes together.

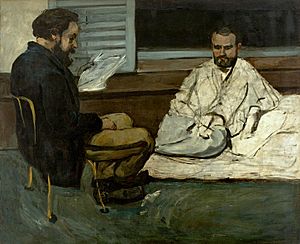

Zola worried about Cézanne's future. In June, he wrote to their friend Baille: "Paul is still the excellent and strange fellow I knew at school. To prove that he hasn't lost any of his originality, I have only to tell you that as soon as he got here he talked about returning." Cézanne painted a portrait of Zola, but he wasn't happy with it and destroyed it. In September 1861, disappointed by the art school's rejection, Cézanne returned to Aix. He worked in his father's bank again.

But in late 1862, he moved back to Paris. His father gave him a monthly allowance to live as an artist. The École des Beaux-Arts rejected him again. So, he went back to the Académie Suisse, which supported Realism. During this time, he met many young artists, including Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Alfred Sisley.

Cézanne was influenced by Gustave Courbet and Eugène Delacroix. These artists wanted to renew art by showing real life. Courbet's followers called themselves "realists." Édouard Manet also broke away from traditional historical painting. He focused on showing his own feelings and freeing art from symbolic meanings.

In 1863, the works of Manet, Pissarro, and Monet were not allowed in the official art show, the Salon de Paris. This made many artists angry. So, Napoleon III created a “Salon des Refusés” (salon of the rejected). Cézanne's paintings were shown there in 1863. The Salon rejected Cézanne's art every year from 1864 to 1869. He kept trying to get into the Salon until 1882. That year, his friend Antoine Guillemet, who was on the Salon jury, helped him. He pretended Cézanne was his student, and Cézanne's painting Portrait de M. L. A. (likely Portrait of Louis-Auguste Cézanne, The Artist's Father, Reading "L'Événement") was shown. It was hung in a bad spot and didn't get much attention. This was his first and last successful entry to the Salon.

In summer 1865, Cézanne returned to Aix. Zola's first novel, La Confession de Claude, was published and dedicated to Cézanne and Baille. In autumn 1866, Cézanne painted many works using a palette knife. These were mostly still lifes and portraits. He spent most of 1867 in Paris and 1868 in Aix. In early 1869, he returned to Paris and met Marie-Hortense Fiquet, a bookbinder's assistant. She was eleven years younger than him.

L'Estaque – Auvers-sur-Oise – Pontoise 1870–1874

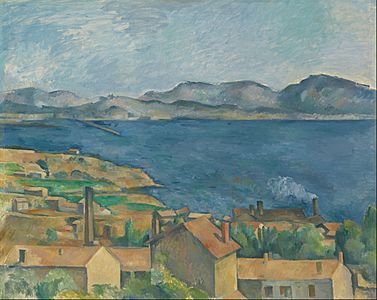

On May 31, 1870, Cézanne was the best man at Zola's wedding in Paris. During the Franco-Prussian War, Cézanne and Hortense Fiquet lived in L'Estaque, a fishing village near Marseille. Cézanne loved the Mediterranean feel of the place and painted there often. He avoided being drafted into the military.

After the Paris Commune ended, the couple returned to Paris in May 1871. Their son, Paul fils, was born on January 4, 1872. Cézanne's mother knew about Hortense and their son, but his father did not. Cézanne feared his father's anger and losing his financial support. His father gave him 100 francs a month.

From late 1872 to 1874, Cézanne lived with Hortense and their son in Auvers-sur-Oise. There, he met Dr. Paul Gachet, an art lover who later treated Vincent van Gogh. Gachet was also a painter and let Cézanne use his studio.

In 1872, Cézanne accepted an invitation from Pissarro to work in Pontoise. Pissarro was a sensitive artist and became a mentor to Cézanne. He convinced Cézanne to use brighter colors and advised him: "Always only paint with the three primary colours (red, yellow, blue) and their immediate deviations." He also told him to avoid drawing outlines. The shapes of things should come from the colors. Cézanne felt that the Impressionist style helped him reach his goals and followed Pissarro's advice. Pissarro later said: "We were always together, but still each of us kept what counts alone: our own feelings."

First Impressionist Exhibitions from 1874

Young painters in Paris felt the Salon de Paris did not support their work. So, they decided to hold their own exhibition, a plan Claude Monet had made in 1867. From April 15 to May 15, 1874, the first group exhibition took place. This group later became known as the Impressionists. Their name came from Monet's painting Impression soleil levant. In a funny magazine called Le Charivari, critic Louis Leroy called the group "Impressionists." The show was held in photographer Nadar's studio.

Pissarro insisted that Cézanne participate, even though some members worried his bold paintings would hurt the show. Cézanne was influenced by their style, but he was often rude, shy, and easily angered. Besides Cézanne, Renoir, Monet, Alfred Sisley, Berthe Morisot, Edgar Degas, and Pissarro also exhibited. Manet refused to join, calling Cézanne "a mason who paints with a trowel." Cézanne especially caused a stir. Critics were angry and made fun of his paintings like Landscape near Auvers and Modern Olympia. In A Modern Olympia, Cézanne used Manet's 1863 painting Olympia as inspiration. Cézanne's version showed the suitor, believed to be a self-portrait.

The exhibition did not make money. Each artist lost over 180 francs.

In 1875, Cézanne met Victor Chocquet, a customs inspector and art collector. Renoir introduced them. Chocquet bought three of Cézanne's works and became his most loyal collector. His purchases helped Cézanne financially. Cézanne did not join the group's second exhibition. But he showed 16 of his works in their third exhibition in 1877. These paintings also received much criticism. Critic Louis Leroy said of Cézanne's portrait of Chocquet: "This peculiar looking head, the colour of an old boot might give [a pregnant woman] a shock and cause yellow fever in the fruit of her womb before its entry into the world." This was the last time Cézanne exhibited with the Impressionists. Another supporter was paint merchant Julien "Père" Tanguy. He gave young painters paint and canvas in exchange for their artworks.

In March 1878, Cézanne's father found out about Hortense and their son. This happened because of a careless letter from Victor Chocquet. His father then cut his monthly allowance in half. Cézanne had money problems and had to ask Zola for help. But in September, his father changed his mind and gave him 400 francs for his family. Cézanne kept moving between Paris and Provence. In the early 1880s, Louis-Auguste built a studio for him at his home, Bastide du Jas de Bouffan. This studio was on the top floor and had a large window for light. Cézanne often stayed in L'Estaque. He painted there with Renoir in 1882 and visited Renoir and Monet in 1883.

In 1881, Cézanne worked in Pontoise with Paul Gauguin and Pissarro. Cézanne returned to Aix at the end of the year. He later accused Gauguin of stealing his ideas. In spring 1882, Cézanne worked with Renoir in Aix and L'Estaque. He visited L'Estaque again in 1883 and 1888. One of his paintings from these trips was The Bay of Marseille seen from L'Estaque. In late 1885 and the following months, Cézanne stayed in Gardanne. This small town near Aix-en-Provence inspired several paintings. Their shapes already hinted at the Cubist style.

Break with Zola and Marriage

Cézanne's long friendship with Émile Zola had grown distant. In 1878, Zola, a successful writer, bought a fancy summer house near Auvers. Cézanne visited him there many times between 1879 and 1885. But Zola's rich lifestyle made Cézanne, who lived simply, feel unsure about himself.

Zola started to see his childhood friend as a failure. In March 1886, Zola published his novel L'Œuvre. The main character, a painter named Claude Lantier, fails to achieve his goals and dies. Zola also put a successful writer, Sandoz, next to the painter Lantier in the book. Monet and Edmond de Goncourt thought the fictional painter was like Édouard Manet. But Cézanne saw himself in many details. He formally thanked Zola for sending the book. For a long time, people thought their friendship ended then. But recently, letters have been found that show their friendship lasted at least a bit longer.

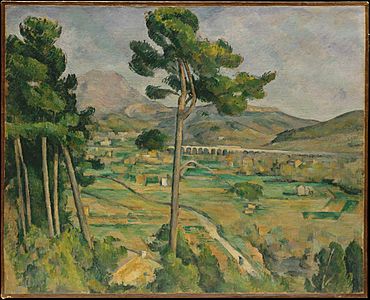

On April 28, 1886, Paul Cézanne and Hortense Fiquet were married in Aix. His parents were there. Their relationship was not based on love anymore. Cézanne was shy around women and afraid of being touched. This fear came from a childhood event where a classmate kicked him. The marriage was mainly to make their fourteen-year-old son Paul a legitimate heir. Cézanne loved his son very much. In the early 1880s, the Cézanne family settled in Provence. They stayed there, except for short trips, from then on. This move showed his new independence from the Paris-based Impressionists. It also showed his strong love for his home region in the south. Hortense's brother had a house near Montagne Sainte-Victoire in L'Estaque. Many paintings of this mountain from 1880 to 1883 and others of Gardanne from 1885 to 1888 are called "the Constructive Period."

Even though their relationship was difficult, Hortense was the person Cézanne painted most often. From the early 1870s to the early 1890s, he painted 26 portraits of Hortense. She sat still and patiently for him during long sessions. In October 1886, after his father died, Cézanne, his mother, and sisters inherited his estate. This included the Jas de Bouffan estate, which greatly improved Cézanne's financial situation. He said later, "My father was a brilliant man. He left me an income of 25,000 francs." By 1888, the family lived comfortably in the Jas de Bouffan manor. This large house and its grounds are now owned by the city and are open to the public.

Exhibitions in 1890 and 1895

Cézanne lived in Paris and increasingly in Aix, without his family. Renoir visited him in January 1888, and they worked together in Jas de Bouffan's studio. In 1890, Cézanne got diabetes. This illness made it even harder for him to get along with people. Cézanne spent a few months in Switzerland with Hortense and their son Paul. He hoped to fix his troubled relationship with Hortense. But it didn't work. He returned to Provence, while Hortense and Paul fils went to Paris. Hortense later returned to Provence due to money problems, but they lived separately. Cézanne moved in with his mother and sister. In 1891, he became a Catholic.

In the same year, he showed three of his works at the Les XX group exhibition in Brussels. Les XX was an art group founded around 1883 by Belgian artists.

In May 1895, Cézanne visited Monet's exhibition at the Durand-Ruel Gallery with Pissarro. He was impressed but later said Monet's best work was from 1868, when he was more influenced by Courbet. With his old classmate Achille Emperaire, Cézanne went to the area around Le Tholonet. He lived in "Château Noir," which is near the Montagne Sainte-Victoire. He often painted the mountains. He also rented a small hut at the nearby Bibémus quarry, which became another subject for his paintings.

Ambroise Vollard, a new gallery owner, held Cézanne's first solo show in November 1895. He displayed 50 of about 150 works Cézanne had sent him. Vollard had met Degas and Renoir in 1894. He also connected with Pierre Bonnard and Édouard Vuillard. When paint dealer Père Tanguy died, Vollard bought works by three artists who were not well-known yet: Cézanne, Gauguin, and van Gogh. Monet was the first to buy a Cézanne painting, followed by other artists like Degas, Renoir, and Pissarro. Later, art collectors started buying them. Prices for Cézanne's works increased greatly, and Vollard profited from his collection.

In 1897, a museum bought a Cézanne painting for the first time. Hugo von Tschudi bought Cézanne's The Mill on the Couleuvre near Pontoise for the Berlin National Gallery.

Cézanne's mother died on October 25, 1897. In November 1899, his sister convinced him to sell the "Jas de Bouffan" property. He moved into a small apartment in Aix-en-Provence. He couldn't buy the "Château Noir" property as planned. He hired a housekeeper, Mme Bremond, who took care of him until he died.

Homage to Cézanne

The art market continued to react well to Cézanne's works. In June 1899, Pissarro wrote from Paris about an auction of the Chocquet collection: "These include thirty-two Cézannes of the first rank [...]. The Cézannes will fetch very high prices and are already estimated at four to five thousand francs.” At this auction, Cézanne's paintings reached high prices for the first time. However, they were still "far below those for paintings by Manet, Monet or Renoir.”

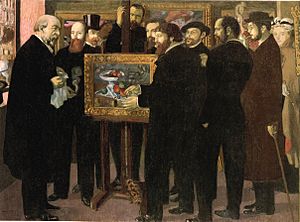

In 1901, Maurice Denis showed his large painting Hommage à Cézanne in Paris and Brussels. The painting shows Ambroise Vollard's gallery. It features Cézanne's painting Still Life with Bowl of Fruit, which used to belong to Paul Gauguin. The writer André Gide bought Hommage à Cézanne and gave it to the Musée du Luxembourg in 1928. It is now in the Musée d'Orsay, Paris. The painting shows many famous artists and critics of the time.

Last Years

In 1901, Cézanne bought land north of Aix-en-Provence. He had his studio built there in 1902 (Atelier de Cézanne, now open to the public). He moved there in 1903. For large paintings like The Bathers, he had a long, narrow opening built in the wall for natural light. That year, Zola died, which saddened Cézanne despite their distant friendship. His health got worse with age. Besides diabetes, he suffered from depression and became very distrustful of people.

Even though the artist was becoming more recognized, hateful articles appeared in the press. He also received many threatening letters. Cézanne's paintings were not liked by the middle-class people of Aix. In 1903, Henri Rochefort visited an auction of paintings that Zola had owned. On March 9, 1903, he wrote a very critical article called "Love for the Ugly." Rochefort claimed that people laughed when they saw paintings by "an ultra-impressionist named Cézanne." The public in Aix was angry. For many days, copies of the newspaper appeared at Cézanne's door with messages asking him to leave town. Cézanne told his coachman, "I don't understand the world and the world doesn't understand me, so I withdrew from the world." In September 1902, Cézanne made his will. He did not include his wife Hortense in his inheritance. He made his son Paul his only heir. Hortense is said to have burned his mother's keepsakes.

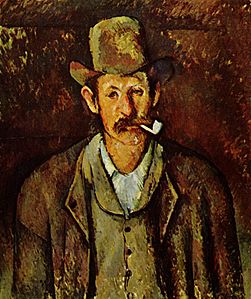

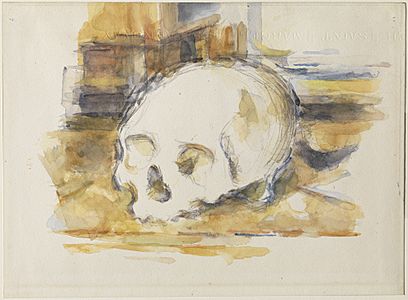

In 1903, he exhibited for the first time at the new Salon d'Automne (Paris Autumn Salon). The painter and art theorist Émile Bernard visited him for a month in February 1904. Bernard later wrote an article about Cézanne. Cézanne was working on a still life with three skulls on an oriental carpet. Bernard said this painting changed color and form every day, even though it looked finished from the start. He saw this work as Cézanne's final message. Bernard said, "Truly, his way of working was a reflection with a brush in his hand." In his still lifes with skulls, Cézanne showed his increasing depression in old age. He had written in letters since 1896 that "life is beginning to be deadly monotonous for me." Cézanne and Bernard continued to write letters until Cézanne's death. Bernard published his memories of Cézanne in 1907.

From October 15 to November 15, 1904, a whole room at the Salon d'Automne was filled with Cézanne's works. In 1905, an exhibition in London also showed his work. The Galerie Vollard exhibited his works in June. The Salon d'Automne followed from October 19 to November 25 with 10 paintings. Art historian Karl Ernst Osthaus visited Cézanne on April 13, 1906, hoping to buy a painting. His wife Gertrud likely took the last photo of Cézanne. Osthaus wrote about his visit in his work A Visit to Cézanne.

Despite his later successes, Cézanne felt he could never fully reach his goals. On September 5, 1906, he wrote to his son Paul: "Finally, I want to tell you that as a painter I am becoming more clairvoyant to nature, but that it is always very difficult for me to realize my feelings. I cannot reach the intensity that unfolds before my senses, I do not possess that wonderful richness of colour that animates nature."

Death

On October 15, 1906, Cézanne was caught in a storm while painting outdoors. After two hours, he decided to go home. But on the way, he collapsed and lost consciousness. A passing laundry cart driver took him home. Because of hypothermia, he got severe pneumonia. His old housekeeper rubbed his arms and legs to help his blood flow. He then woke up. The next day, Cézanne went into the garden to work on his last painting, Portrait of the Gardener Vallier. He also wrote an impatient letter to his paint dealer, complaining about a delay in paint delivery. Later, he fainted again. Vallier called for help. Cézanne was put to bed and never left it. His wife Hortense and son Paul received a telegram from the housekeeper, but they arrived too late. He died a few days later, on October 22, 1906, from pneumonia at age 67. He was buried in the Saint-Pierre Cemetery in his hometown.

Cézanne's Art Periods

Cézanne's work and life can be divided into different periods.

Dark Period, Paris, 1861–1870

Cézanne's early "dark" period was influenced by French Romanticism and early Realism. He looked up to Eugène Delacroix and Gustave Courbet. His paintings from this time have thick paint, strong dark colors, and deep shadows. He used pure black and other dark tones. Sometimes, he added a few white, green, or red brushstrokes to brighten things up. The subjects were portraits of family or dark, emotional scenes. These paintings were very different from his earlier watercolors and sketches.

In 1866–67, Cézanne painted many works using a palette knife, inspired by Courbet. He called these works, mostly portraits, une couillarde (a strong word for showing off manliness). These paintings showed a style that was "as unified as Impressionism was fragmentary." Later works from this dark period include violent subjects like Women Dressing (c. 1867), The Abduction (c. 1867), and The Murder (c. 1867–68).

Impressionist Period, Provence and Paris, 1870–1878

Camille Pissarro lived in Pontoise. He and Cézanne painted landscapes together there and in Auvers. For a long time, Cézanne called himself Pissarro's student, even calling him "God the Father." He also said, "We all stem from Pissarro." Because of Pissarro, Cézanne started using brighter colors. His paintings became much lighter. He used a color palette based only on yellow, red, and blue. He stopped using thick, heavy paint and started using the loose, side-by-side brushstrokes of the Impressionists.

During these years, he painted fewer portraits and figure compositions. Cézanne then created landscapes where the feeling of deep space became less clear. He saw objects as basic geometric shapes. This way of painting was used for the whole picture. The brushstrokes treated distant areas the same way as close objects. This made the painting look like it had depth from far away. Cézanne moved away from traditional picture space. But he also made sure his paintings didn't look as blurry as some Impressionist works.

Mature Period, Provence, 1878–1890

Next came the "period of synthesis." In this time, Cézanne completely moved away from the Impressionist style. He made forms solid by applying paint in diagonal strokes. He removed traditional perspective to create depth. He focused on balancing the parts of his paintings. During this period, he painted more landscapes and figures. He wrote to his friend Joachim Gasquet: "The coloured surfaces, always the surfaces! The colourful place where the soul of the surfaces trembles, the prismatic warmth, the encounter of the surfaces in the sunlight. I design my surfaces with my shades on the palette, understand me! […] The areas must be clearly visible. Definitely [...] but they have to be distributed correctly, they have to flow into one another. Everything has to play together and yet create contrasts. It's all about the volume!"

Cézanne also focused on still lifes from the late 1880s. He didn't use linear perspective. Instead, he painted objects in sizes that made sense for the painting's balance. For example, a pear might be extra large to make the composition exciting. He set up his arrangements in his studio. Besides fruit, he used jugs, pots, and plates. Sometimes, a small statue or a puffy white tablecloth added a rich look. The goal was not to show the objects themselves, but the arrangement of shapes and colors on the surface.

Cézanne built his compositions from small dabs of paint spread across the canvas. From these, the shape and volume of the object slowly appeared. Balancing these color patches took a long time. So, Cézanne often worked on a painting for many months. At first, he only painted family or friends. But when he had more money, he hired a professional model. This was a young Italian named Michelangelo di Rosa. He posed for The Boy in the Red Vest (1888–1890), one of Cézanne's most famous paintings. Di Rosa appeared in four paintings and two watercolors.

Final Period, Provence, 1890–1906

Many of his later works, called the "lyrical period," show figures in landscapes, like his series of bathers. Cézanne created about 140 paintings and sketches of bathing scenes. These show his love for classical art, which aimed to bring people and nature together in peaceful, ideal settings. In his last seven years, he painted three large versions of The Great Bathers. The one in Philadelphia is the largest, measuring 208 × 249 cm. Cézanne focused on the composition and how shapes and colors, nature and figures, worked together. He used sketches and photographs as guides for these paintings.

Cézanne painted five versions of The Card Players between 1890 and 1895. The same person is shown in different ways. For The Card Players, he used farmers and day laborers from near Jas de Bouffan as models. These are not just everyday scenes. The painting is carefully built using strict rules of color and form.

The area around the Montagne Sainte-Victoire was very important in his later years. From a spot above his studio, he painted many views of the mountain. Cézanne believed that observing nature carefully was key to his painting. He said, "In order to paint a landscape correctly, I first have to recognize the geological stratification." He painted over 30 oil paintings and 45 watercolors of the mountains. In the 1890s, he wrote to a friend that "art is a harmony parallel to nature."

Cézanne focused on watercolor painting in his later work. He found that his painting method worked well with watercolors. His late watercolors also influenced his oil paintings. For example, in his study with bathers (1902–1906), he used "empty spaces" surrounded by color. Art critic Roger Fry noted in his 1927 book that watercolor technique strongly influenced Cézanne's oil paintings after 1885. Many of his watercolors are as important as his oil paintings. Landscapes are the most common subjects in his watercolors, followed by figures and still lifes. Portraits are rarer in his watercolors than in his other works.

Artistic Style

Cézanne's Method

Cézanne's early work often showed figures in landscapes. These paintings had large, heavy figures imagined in the scenery. Later, he became more interested in painting what he saw directly. He slowly developed a light, airy painting style. However, in his mature work, Cézanne developed a solid, almost architectural way of painting. He always tried to truly observe the world and show it accurately in paint. To do this, he broke down what he saw into simple shapes and color areas. He said, "I want to make of impressionism something solid and lasting like the art in the museums." He also said he was recreating Poussin "after nature." This showed his wish to combine observing nature with the lasting quality of classical art.

Like old masters, drawing was the base of Cézanne's painting. But the most important thing was to focus on the object, or simply to see. He said, "All the painter’s intentions must be silent. He should silence all voices of prejudice. Forget! Forget! create silence! Be a perfect echo. […] The landscape is reflected, becomes human, thinks in me. […] I climb with her to the roots of the world. we germinate A tender excitement seizes me and from the roots of this excitement then rises the juice, the colour. I was born in the real world. I see! […] In order to paint that, then, the craft must be used, but a humble craft that obeys and is ready to transmit unconsciously.”

Besides oil paintings and watercolors, Cézanne left over 1200 drawings. These drawings were hidden during his lifetime and only became interesting to collectors in the 1930s. They were his working materials, showing detailed sketches, notes, and the steps he took to create a painting. They helped him build the overall structure and define objects in his pictures. Even when he was old, he drew portraits and figures based on old sculptures and Baroque paintings from the Louvre. This helped him understand how to make shapes stand out. The black and white of his drawings were very important for his color designs.

Paul Cézanne was one of the first artists to break down objects into simple geometric shapes. In a famous letter from April 15, 1904, to painter Émile Bernard, he wrote: "Treat nature according to cylinder, sphere, and cone and put the whole in perspective, like this that each side of an object, of a surface, leads to a central point […]" Cézanne used these ideas in his paintings of Montagne Sainte-Victoire and his Still-Lifes. He saw a mountain as layers of forms, spaces, and structures rising from the ground.

Émile Bernard wrote about Cézanne's unusual way of working: "He began with the shadow parts and with one spot, on which he put a second, larger one, then a third, until all these shades, covering each other, modelled the object with their colouring. It was then that I realized that a law of harmony was guiding his work and that these modulations had a direction preordained in his mind.” Cézanne believed this "preordained direction" was the real secret to painting harmony and the illusion of depth. He told collector Karl Ernst Osthaus in 1906 that the most important thing in a picture is how distant parts meet. The color must show every jump into depth.

Optical Phenomena

Cézanne was interested in simplifying natural forms into basic geometric shapes. He wanted to "treat nature in terms of the cylinder, the sphere and the cone." For example, a tree trunk could be seen as a cylinder, and an apple as a sphere. Cézanne also wanted to show how we truly see things. He explored binocular vision (seeing with two eyes). He painted slightly different views of the same thing at the same time. This gave viewers a feeling of depth that was different from older ideas of single-point perspective. His interest in new ways of showing space and volume came from the popularity of stereoscopy (3D viewing) at the time.

Aller sur le motif, Sensation, and Realization

Cézanne often used these terms to describe his painting process. First, there was the "motif." This wasn't just the subject of the picture. It was also the reason for his endless work of observing and painting. Aller sur le motif, or "going to the motif," meant connecting with an outside object that moved him deeply. This feeling then had to be turned into a painting.

"Sensation" was another key word for Cézanne. First, it meant what he saw, like an "impression" or a visual feeling from the object. But it also included the emotion he felt about what he saw. Cézanne didn't focus on just copying the object. He focused on the sensation: "Painting from nature does not mean copying the object, it means realizing its sensations." Color was the link between things and sensations. Cézanne didn't fully explain if color came from the objects or from his own vision.

Cézanne used "réalisation" (realization) to describe the actual painting process. He worried about failing at this until the end of his life. Several things had to be "realized" at once: the motif in all its detail, his feelings about the motif, and finally, the painting itself. The painting's completion would bring the other "realizations" to life. So, "painting" meant letting the opposing actions of taking in (impression) and giving out (expression) combine into one single act. "Realization in art" became a central idea in Cézanne's thoughts and actions.

Dating and Cataloguing

It can be hard to know the exact dates for Cézanne's works. He rarely dated his paintings. He also worked on some pictures for months or even years until he was happy with them. Cézanne himself thought many of his paintings were unfinished. For him, painting was a never-ending process.

Organizing Cézanne's works into a catalog was a difficult job. Ambroise Vollard made the first attempt. The first full catalog was published by Lionello Venturi in 1936. This two-volume book, Cézanne: Son Art, Son Oeuvre, was the main catalog for over fifty years. Later, John Rewald continued Venturi's work. Rewald disagreed with many of Venturi's dates and some of his ideas about which works were Cézanne's. So, he started a completely new catalog. Rewald's catalog of Cézanne's watercolors was published in 1983. The lack of dates on paintings and unclear descriptions like Paysage (Landscape) caused confusion. Rewald made a list of works that could be dated without guessing the style. He also used documents to track where Cézanne lived. Another method was to rely on the memories of people Cézanne painted. For example, Cézanne's Portrait of the Critic Gustave Geffroy was confirmed by the sitter as 1895. Lake Annecy was dated because Cézanne only visited that lake once, in 1896.

Rewald died in 1994 and couldn't finish his work. His helpers, Walter Feilchenfeldt Jr. and Jayne Warman, completed the catalog. It was published in 1996 as The Paintings of Paul Cézanne: A Catalog Raisonne – Review. It includes 954 works Rewald wanted to record. Feilchenfeldt, Warman, and David Nash later created the first complete online catalog of Cézanne's paintings, watercolors, and drawings.

Cézanne's Legacy

Friends and Artists Remember Cézanne

Cézanne's childhood friend, the writer Émile Zola, doubted Cézanne's artistic abilities. In 1861, Zola said, "Paul may have the genius of a great painter, but he will never have the genius to actually become one. The slightest obstacle drives him to despair." Indeed, Cézanne's self-doubt and refusal to compromise his art made his friends see him as an unusual person.

Cézanne's works were often rejected by the official Salon in Paris. Art critics made fun of them when they were shown with the Impressionists. Yet, during his lifetime, younger artists who visited his studio in Aix saw Cézanne as a master. Among the Impressionists, Cézanne was highly respected. Camille Pissarro, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Claude Monet, and Edgar Degas spoke excitedly about his work. Pissarro said, "I think it will be centuries before we get an account of it."

His friend and mentor Pissarro painted a portrait of Cézanne in 1874. In 1901, Maurice Denis, a co-founder of the Nabis group, created Hommage à Cézanne. This painting shows Cézanne's Still Life with Fruit on an easel among artist friends at the Vollard Gallery. This painting, once owned by Paul Gauguin, was later bought by French writer André Gide. It is now at the Musée d'Orsay.

Art Criticism of His Time

The first Impressionist exhibition in Paris in 1874 received a lot of criticism. Audiences and critics, who believed in the "ideal" art of the École de Beaux Arts, laughed out loud. One critic joked that Monet painted by loading his colors into a gun and shooting them at the canvas. Another critic danced in front of a Cézanne painting, shouting, “Hugh! […] I am the walking impression, the avenging palette knife, Monet's 'Boulevard des Capucines' and 'The Modern Olympia' by Mr. Cézanne. Hugh! Hugh!

In 1883, French writer Joris-Karl Huysmans suggested that Cézanne's view of subjects was distorted by astigmatism (an eye condition). Five years later, in La Cravache magazine, his opinion became more positive. He described Cézanne's works as “strange yet real” and as “revelations.”

Art dealer Ambroise Vollard first saw Cézanne's works in 1892. Paint dealer Tanguy had displayed them in his shop in Montmartre in exchange for art supplies. Vollard remembered that few people were interested. He said, "since it was not yet fashionable at the time to buy 'atrocious works' expensively, not even cheaply." Tanguy even took interested buyers to the painter's studio. There, small pictures cost 40 francs and large ones 100 francs. The Journal des Artistes newspaper reflected the general feeling, asking if its sensitive readers would be sickened by "these oppressive abominations, which exceed the measure of evil permitted by law."

Gustave Geffroy was one of the few critics who judged Cézanne's work fairly during his lifetime. In 1894, he wrote in the Journal that Cézanne had become a kind of pioneer for younger artists. He said there was a direct link between Cézanne's painting and that of Gauguin, Bernard, and even Vincent van Gogh. A year later, after the successful exhibition at the Vollard Gallery in 1895, Geffroy wrote again: "He is a great truth fanatic, fiery and naive, harsh and nuanced. He will go to the Louvre.” Between these two articles, Cézanne painted Geffroy's portrait, but he left it unfinished because he was not happy with it.

Exhibitions After His Death

Two special art shows honored Cézanne after he died in 1907. From June 17 to 29, the Bernheim-Jeune gallery in Paris showed 79 of his watercolors. Then, from October 5 to November 15, the 5th Salon d'Automne honored him. It showed 49 paintings and seven watercolors in two rooms. Many important people visited, including art historian Julius Meier-Graefe and poet Rainer Maria Rilke. These two exhibitions inspired many artists, such as Georges Braque, André Derain, Wassily Kandinsky, Henri Matisse, and Pablo Picasso. They gained important ideas for 20th-century art.

In 1910, some of Cézanne's paintings were shown in the Manet and the Post-Impressionists exhibition in London. Another show followed in 1912. This exhibition was started by painter and critic Roger Fry. He wanted to introduce English art lovers to the works of Édouard Manet, Georges Seurat, Vincent van Gogh, Paul Gauguin, and Cézanne. Fry used the name "Post-Impressionist" to describe this style. Even though critics and the public didn't like the exhibition, it was very important for modern art. Fry saw the great value in how artists like van Gogh and Cézanne showed their personal feelings in their paintings. Visitors at the time couldn't understand this yet. Cézanne's first exhibition in the United States was in 1910/11 in New York. In 1913, his works were shown at the Armory Show in New York. This was a groundbreaking exhibition of modern art, but it also received criticism and ridicule. Today, these artists, who were criticized in their time, are seen as the founders of modern art.

Influence on Modern Art

Many "productive" misunderstandings about Cézanne's work and ideas greatly influenced the development of modern art. Many artists, from the 20th century, referred to him and used parts of his creative ideas for their own art. In 1910, Guillaume Apollinaire said that "most of the new painters claim to be successors of this serious painter who was only interested in art."

Right after Cézanne died in 1906, people started studying his work closely. This was encouraged by a large exhibition of his watercolors in 1907 and a show of his paintings in October 1907 in Paris. Among young French artists, Henri Matisse and André Derain were the first to be very excited about Cézanne. Then came Picasso, Fernand Léger, Georges Braque, Marcel Duchamp, and Piet Mondrian. This excitement lasted a long time. In 1949, the eighty-year-old Matisse said he owed the most to Cézanne's art. Braque also called Cézanne's influence on his art an "initiation." In 1961, he said, "Cézanne was the first to turn away from the learned mechanized perspective." Picasso admitted that "he was the only master for me ..., he was a father figure to us: it was he who offered us protection."

However, Cézanne expert Götz Adriani notes that the Cubists, especially Albert Gleizes and Jean Metzinger, misunderstood Cézanne. They put Cézanne at the beginning of their painting style in their 1912 book Du "Cubisme". But they mostly ignored how Cézanne was inspired by observing nature. Adriani points to misunderstandings that came from Émile Bernard's 1907 paper. This paper referred to a 1904 letter where Cézanne advised him to "treat nature according to cylinder, sphere and cone." More misunderstandings can be found in Kazimir Malevich's 1919 text On the New Systems in Art. Cézanne's quote was not meant to change how nature was experienced by focusing on cubic shapes. He was more interested in matching object forms and colors from different angles in the picture.

One example of Cézanne's influence on modern art is his 1888 painting Mardi Gras. It shows his son Paul and his friend Louis Guillaume in costumes. Picasso was inspired by this for his harlequin theme in his pink period. Matisse, in turn, used the theme of Cézanne's The Great Bathers from the Philadelphia Museum of Art for his 1909 painting The Bathers.

Many artists were inspired by Cézanne's work. Painter Paula Modersohn-Becker saw his paintings in Paris in 1900 and was deeply impressed. Shortly before she died, she wrote in a letter: "I am thinking and thinking a lot these days about Cézanne and how he is one of the three or four painters who struck me like a thunderstorm or a major event.” Paul Klee wrote in his diary in 1909: “Cézanne is a teacher par excellence for me.” The artist group Der Blaue Reiter referred to him in their 1912 book. Franz Marc wrote about the connection between El Greco and Cézanne. He saw their works as opening doors to a new era of painting. Kandinsky, who saw Cézanne's painting at the 1907 show, mentioned Cézanne in his 1912 book On the Spiritual in Art. He found a "strong resonance of the abstract" in Cézanne's work. El Lissitzky stressed Cézanne's importance for the Russian avant-garde around 1923. Lenin even suggested building monuments to heroes of the world revolution in 1918, including Courbet and Cézanne. Next to Matisse, Alberto Giacometti studied Cézanne's style the most. Aristide Maillol worked on a Cézanne monument in 1909, but the city of Aix-en-Provence rejected it. Cézanne was also important for newer artists. Jasper Johns called him the most important role model, along with Duchamp and Leonardo da Vinci.

Cézanne's work, along with that of Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin, greatly influenced Matisse and others before Fauvism and Expressionism. His ideas about simplifying shapes and optical effects inspired Picasso, Braque, Metzinger, Gleizes, Gris, and others. They experimented with showing the same subject from many angles, which led to breaking apart forms. Cézanne thus started one of the most important areas of art exploration in the 20th century. This greatly affected the development of modern art. Picasso called Cézanne "the father of us all" and his "one and only master!" Other painters like Edgar Degas, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Paul Gauguin, Kasimir Malevich, Georges Rouault, Paul Klee, and Henri Matisse recognized Cézanne's genius.

Writer Ernest Hemingway compared his writing to Cézanne's landscapes. He wrote in A Moveable Feast that he was "learning something from the painting of Cézanne that made writing simple true sentences far from enough to make the stories have the dimensions that I was trying to put in them."

Cézanne's painting The Boy in the Red Vest was stolen from a Swiss museum in 2008. It was found in a Serbian police raid in 2012.

Films About Cézanne

- Une visite au Louvre, 2004. This film by Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet is about Cézanne. It is based on conversations with the painter that were published after his death. The film shows Cézanne walking through the Louvre museum, looking at other artists' paintings.

- In 2006, for the 100th anniversary of Cézanne's death, two documentaries from 1995 and 2000 about Paul Cézanne and his favorite subject, La Montagne Sainte-Victoire, were re-released. Cézanne's triumph was also re-filmed for the anniversary.

- The Violence of the Motive, 1995. A film by Alain Jaubert. A mountain near his hometown became Cézanne's main subject. He painted La Montagne Sainte-Victoire from different angles and in different seasons over 80 times. The film explores why this mountain became such an obsession for him.

- Cézanne – the Painter, 2000. A film by Elisabeth Kapnist. This film tells the story of Cézanne's passion and lifelong artistic search. It covers his childhood, his friendship with Zola, and his encounter with Impressionism.

- The Triumph of Cézanne, 2006. A film by Jacques Deschamps. Deschamps uses the 100th anniversary of Cézanne's death to trace how he became a legend. Cézanne faced rejection and misunderstanding before becoming a famous artist.

- The 2016 film Cézanne and I explores the friendship between the artist and Émile Zola.

Cézanne and Philosophy

French philosopher Jean-François Lyotard believed Cézanne had a "sixth sense." He felt reality as it was forming, before normal perception finished it. So, the painter touched on the sublime when he saw the amazing quality of the mountain landscape. This could not be shown with normal language or painting techniques. Lyotard said, "One can also say that the uncanniness of the oil paintings and watercolours dedicated to mountains and fruits derives both from a deep sense of the disappearance of appearances and from the demise of the visible world."

French philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty studied Cézanne's style and beliefs about painting. Merleau-Ponty is known for his ideas on how we experience things. In his 1945 essay "Cézanne's Doubt", Merleau-Ponty discusses how Cézanne gave up classic art rules. These included perfect arrangements, single viewpoints, and outlines that held color. Cézanne wanted to get a "lived perspective" by capturing all the complex things an eye sees. He wanted to truly see and feel the objects he painted, not just think about them. He wanted "sight" to also be "touch." He sometimes took hours to make a single brushstroke. Each stroke needed to show "the air, the light, the object, the composition, the character, the outline, and the style." A still life might have taken Cézanne one hundred painting sessions, while a portrait took him around one hundred and fifty. Cézanne believed that when he painted, he was capturing a moment in time that would not come back. The atmosphere around what he was painting was part of the real feeling he was trying to show. Cézanne stated: "Art is a personal apperception, which I embody in sensations and which I ask the understanding to organize into a painting."

Art Market

The value of Cézanne's art has increased a lot. His painting Rideau, Cruchon et Compotier sold for $60.5 million in 1999. This was the fourth-highest price for a painting at that time and the most expensive still life.

Cézanne's watercolor Still Life with Green Melon set a record for a work on paper at auction. It sold for $25.5 million in 2007, much higher than its estimated price of $18 million. A watercolor study for The Card Players series, thought to be lost for sixty years, sold for $19.1 million in 2012.

One of the five versions of Cézanne's The Card Players was sold in 2011 to the Royal Family of Qatar. The price was estimated between $250 million and $300 million. This was a new record for the highest price paid for a painting at that time. This record was broken in November 2017 by Salvator Mundi by Leonardo da Vinci. The Card Players is now the third most expensive painting ever, after the sale of Interchange by Willem de Kooning.

On November 8, 2022, $138 million was paid for the painting La Montagne Sainte-Victoire. This happened at the Paul Allen collection sale in New York City. It set a new record for a Cézanne work sold at auction.

Nazi-Looted Art Claims

In 2000, French courts ordered the seizure of Cézanne's “The sea at l’Estaque.” It was part of an exhibition at the Musée du Luxembourg. This was because of a claim that Nazis had stolen it from gallery owner Josse Bernheim-Jeune.

In 2020, a Cézanne painting from the Buehrle collection was investigated. The painting, Paysage, had already been noted as possibly problematic in a 2015 book. In a newspaper, Keller said the painting's history had been "whitewashed." Keller pointed out that the foundation's description did not mention that the pre-war owners, Berthold and Martha Nothmann, were forced to flee Germany as Jewish people in 1939.

Cézanne's Provence

Visitors to Aix-en-Provence can explore Cézanne's favorite landscapes. There are five marked trails from the city center. They lead to Le Tholonet, the Jas de Bouffan, the Bibémus quarry, the banks of the River Arc, and the Les Lauves workshop.

The Atelier Les Lauves (Cézanne's studio) has been open to the public since 1954. An American foundation, started by James Lord and John Rewald, made this possible. They bought it with money from 114 donors. They bought it from the previous owner and gave it to the University of Aix. In 1969, the studio was given to the city of Aix. Visitors can see Cézanne's furniture, easel, and palette. They can also see objects that appear in his still lifes, and some original drawings and watercolors.

During his lifetime, most people in Aix made fun of Cézanne. More recently, they even named a university after him. In 1973, the Paul Cézanne University was founded in Aix-en-Provence. It had departments for law, political science, business, natural sciences, and technology. In 2011, it joined with two other universities to form the University of Aix-Marseille.

Because they rejected his works in the past, the Musée Granet in Aix had to borrow paintings from the Louvre. This was so they could show visitors works by their city's famous son. In 1984, the museum received eight paintings and some watercolors, including a scene from the Bathers series and a portrait of Mme Cézanne. Thanks to another gift in 2000, nine Cézanne paintings are now on display there.

Gallery

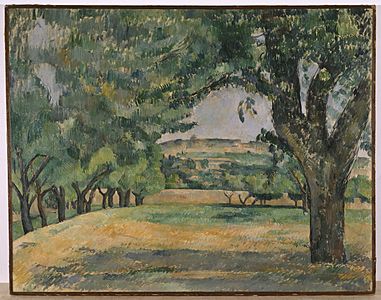

Landscapes

-

Mont Sainte-Victoire

1882–1885

Metropolitan Museum of Art -

The Neighborhood of Jas de Bouffan

1885-1887

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Thannhauser Collection -

Maison Maria on the way to the Château Noir

1895

Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, Texas -

Château Noir

1900–1904

National Gallery of Art, Washington, US -

Mont Sainte-Victoire and Château Noir

1904–05

Bridgestone Museum of Art, Tokyo, Japan

Still Life Paintings

-

Still Life with an Open Drawer

1867–1869

Musée d'Orsay -

Flowers in a Rococo Vase

1876

National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C. -

Still Life with Cherries and Peaches

1885-87

Los Angeles County Museum of Art -

Still Life with Fruit Basket

1888-90

Musée d'Orsay, Paris -

The Basket of Apples

1890–1894

Art Institute of Chicago -

Still Life, Drapery, Pitcher, and Fruit Bowl

1893–1894

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York City -

Still Life with a Teapot

1902-05

National Museum Cardiff

Portraits and Self-Portraits

-

Portrait of Uncle Dominique

1865–1867

Metropolitan Museum of Art -

Self-portrait

1880–81

National Gallery, London -

Self-portrait

1879–1882

Kunstmuseum Bern -

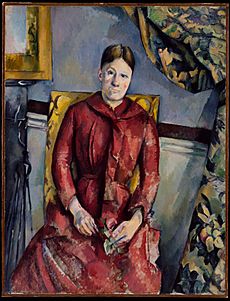

Madame Cézanne

1885–1887

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum -

Portrait of Paul Cézanne's Son

Pastel

1888–1890

The National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. -

Madame Cézanne in a Red Dress

c. 1890–1894

São Paulo Museum of Art -

Boy in a Red Waistcoat

1888–1890

National Gallery of Art -

Self-portrait with Beret

1898–1900

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston -

Woman with a Coffeepot

Oil on canvas

c. 1895

Musée d'Orsay

Bathers

Watercolors

-

River with the Bridge of the Three Sources

1906

Cincinnati Art Museum

See also

In Spanish: Paul Cézanne para niños

In Spanish: Paul Cézanne para niños

- List of paintings by Paul Cézanne

- Cézanne (typeface)

- Post-Impressionism

- Marie-Hortense Fiquet

- List of artwork associated with Agnes E. Meyer

- Croix de Provence on the Montagne Sainte-Victoire