Chimor facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Kingdom of Chimor

Chimor

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 900–1470 | |||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Status | Culture | ||||||||

| Capital | Chan Chan | ||||||||

| Common languages | Mochica, Quingnam | ||||||||

| Religion | Polytheist | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

| King of Chimor | |||||||||

|

• 900?–960?

|

Tacaynamo | ||||||||

|

• 960?–1020?

|

Guacricaur | ||||||||

|

• 1020?–1080?

|

Ñancempinco | ||||||||

| Historical era | Late Intermediate | ||||||||

|

• Established

|

c. 900 | ||||||||

| 1470 | |||||||||

|

|||||||||

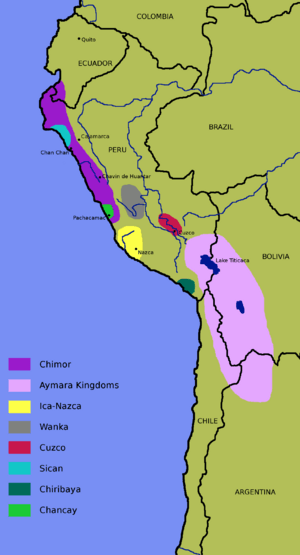

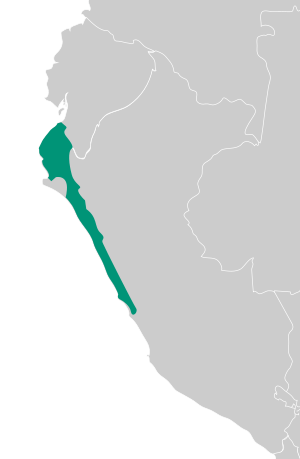

The Chimor Kingdom (also called the Chimú Empire) was a powerful group of people known as the Chimú culture. This culture started around 900 AD. It grew after the Moche culture ended. The Chimú Kingdom was later taken over by the Inca emperor Topa Inca Yupanqui around 1470. This was about 50 years before the Spanish arrived in the area.

Chimor was the largest kingdom during the Late Intermediate Period. It stretched for about 1,000 kilometers (620 miles) along the coast.

Some valleys joined the Chimú willingly. But the Sican culture became part of the kingdom through conquest. The Chimú were also greatly influenced by older cultures like the Cajamarca and Wari cultures. Legend says their capital city, Chan Chan, was founded by Taycanamo. He supposedly arrived by sea.

The Chimú Kingdom was the last group that could have stopped the Inca Empire. But the Inca conquest began in the 1470s. Emperor Topa Inca Yupanqui defeated the Chimú ruler, Minchancaman. The Inca takeover was almost complete when Huayna Capac became emperor in 1493.

The Chimú people lived in a desert strip on the northern coast of Peru. Rivers in this area created fertile valley plains. These plains were flat and perfect for irrigation. Farming and fishing were both very important to the Chimú economy.

The Chimú worshipped the moon. Unlike the Inca, they thought the moon was more powerful than the sun. Offerings were a big part of their religious ceremonies. A common offering was the shell of the Spondylus shellfish. These shells only live in warm coastal waters near modern-day Ecuador. Spondylus shells were linked to the sea, rain, and good crops. They were highly valued and traded by the Chimú. Trading these shells was important for their economy and politics.

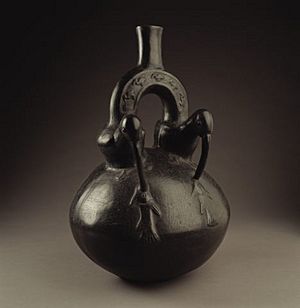

The Chimú people are famous for their unique black pottery. They were also skilled metalworkers. They used copper, gold, silver, bronze, and tumbaga (a mix of copper and gold). Their pottery often looked like animals or human figures on a square bottle. The shiny black color of most Chimú pottery came from firing it at high temperatures in a closed kiln. This stopped oxygen from reacting with the clay.

Contents

History of the Chimú Kingdom

Early Beginnings

The oldest civilization on Peru's north coast was the Moche or Mochica. This period is sometimes called Early Chimú. It ended around 700 AD. This culture was centered in the Chicama, Moche, and Viru Valleys. Many large pyramids made of adobe bricks come from this early time. Early Chimú burial sites have also been found. People were usually buried stretched out in special tombs. These tombs were rectangular, lined with adobe, and had small spaces for bowls.

Early pottery was known for its realistic shapes and painted scenes.

How the Chimú Expanded

The Chimú culture grew in the same area where the Mochica had lived. This happened during the time of the Wari Empire in Peru. The Chimú were a coastal culture. Their capital, Chan Chan, was founded by Taycanamo, who arrived by sea. The kingdom started in the Moche Valley, north of modern-day Lima. It later grew to include Arequipa.

The Chimú Kingdom appeared around 900 AD. Its capital was Chan Chan, near Trujillo. Taycanamo is believed to have founded the kingdom there. His son, Guacri-caur, conquered the lower part of the valley. Then, Guacri-caur's son, Nancen-pinco, truly built the kingdom. He conquered the upper Moche Valley and nearby valleys like Sana, Pacasmayo, Chicama, Viru, Chao, and Santa.

The last Chimú kingdom is thought to have been founded in the early 1300s. Nacen-pinco likely ruled around 1370. Seven rulers followed him, whose names are not known. Minchancaman was the ruler when the Inca conquered the Chimú (between 1462 and 1470). This great expansion happened during the later period of Chimú civilization, called Late Chimú. But the Chimú territory grew over many stages and generations.

The Chimú expanded to control a huge area and many different groups of people. Some valleys joined peacefully. But the Sican culture was taken over by force. At its peak, the Chimú reached the desert coast up to the Jequetepeque River in the north. Pampa Grande in the Lambayeque Valley was also ruled by the Chimú.

To the south, they expanded as far as Carabayllo. Their southward growth was stopped by the powerful valley of Lima. Historians and archaeologists still debate how far south they truly went.

How the Chimú Ruled

Chimú society had a four-level system of power. A strong group of leaders ruled from administrative centers. This power was based in the walled cities, called ciudadelas, at Chan Chan. The leaders at Chan Chan showed their power by organizing workers to build the Chimú's canals and irrigated fields.

Chan Chan was the most important place in the Chimú system. Farfán, in the Jequetepeque Valley, was a less important center. This way of organizing things was set up quickly when they conquered the Jequetepeque Valley. This suggests the Chimú created this system early in their expansion. Local leaders in conquered areas were brought into the Chimú government at lower levels. These lower-level centers managed land, water, and workers. The higher-level centers moved resources to Chan Chan or made other big decisions.

Rural sites were used as engineering bases while canals were built. Later, they became maintenance sites. Many broken bowls found at Quebrada del Oso suggest this. The bowls were likely used to feed the many workers who built and maintained the canal. These workers were probably fed and housed by the state.

The Fall of the Chimú

The Chimú Kingdom ruled these social classes until the Inca Empire arrived. Chimor was the last Andean kingdom that could have stopped the Inca. But the Inca conquest began in the 1470s. Topa Inca Yupanqui defeated the Chimú emperor Minchancaman. The conquest was almost finished when Huayna Capac became emperor in 1493. The Inca moved Minchancaman, the last Chimú emperor, to Cusco. They also took gold and silver to decorate their temple, the Qurikancha.

Chimú Economy and Daily Life

The capital city, Chan Chan, had a system where leaders controlled information. This suggests a kind of government system. The economy worked by importing raw materials. These materials were then turned into valuable goods by skilled workers in Chan Chan. The leaders in Chan Chan made decisions about organizing things. They controlled the making, storing, and sharing of food and products.

Most people in each ciudadela were artisans. In the later Chimú period, about 12,000 artisans lived and worked in Chan Chan alone. They were involved in fishing, farming, crafting, and trading. Artisans were not allowed to change their job. They were grouped in the ciudadela based on their skill. Archaeologists noticed a big increase in Chimú craft production. They think artisans might have been brought to Chan Chan from other areas conquered by the Chimú. Since there's proof of both metalwork and weaving in the same homes, both men and women likely worked as artisans.

They fished, farmed, and worked with metals. They also made pottery and textiles from cotton and the wool of llama, alpaca, and vicuña. People used reed fishing canoes (like the one shown in the image). They also hunted and traded using bronze coins.

Farming and Food

The Chimú grew mainly through advanced farming methods and water systems. They connected valleys to create large farming areas. An example is the Chicama-Moche complex, which joined two valleys. They also had excellent farming techniques that made their cultivated areas stronger. Huachaques were sunken farms. Here, land was dug out to reach moist, sandy soil underneath. The Tschudi complex is an example of this.

The Chimú used walk-in wells, similar to those of the Nazca, to get water. They also built reservoirs to hold river water. This system made the land more productive, which increased Chimú wealth. It probably helped create their organized government. The Chimú grew beans, sweet potato, papaya, and cotton using their water systems.

This focus on large-scale irrigation continued until the Late Intermediate period. Then, they shifted to a more specialized system. This system focused on bringing in and sharing resources from nearby communities. It seems there was a complex network of sites that provided goods and services for Chimú survival. Many of these sites produced things the Chimú could not.

Many sites relied on sea resources. But after farming became common, more sites were built further inland. Here, sea resources were harder to get. Raising llamas became a way to get more meat. By the Late Intermediate period and Late Horizon, inland sites used llamas as a main resource. However, they still kept in touch with coastal sites for extra sea resources. They also made masks.

Chimú Technology

One of the earliest known examples of long-distance communication is a Chimú device. It had two resin-coated gourds connected by a 75-foot length of twine. Only one has been found. We don't know who made it or how it was used.

How Rulers Passed on Power

The Chimú capital, Chan Chan, had many special living areas called ciudadelas. These were not all used at the same time. Instead, they were used one after another. This was because Chimú rulers practiced "split inheritance." This meant the next ruler had to build their own palace. After a ruler died, all their wealth was given to more distant relatives.

Chimú Art and Craftsmanship

Shell Art

The Chimú people highly valued mollusk shells. They were important for trade and politics as a luxury item. Shells often showed high status and divine power. The Chimú used the shell of Spondylus, a type of marine mollusk, in their art.

The most common Spondylus species in Peru were Spondylus calcifer and Spondylus princeps. Spondylus calcifer has red and white colors and was used for beads and artifacts. It was easier to get. The Spondylus princeps, known as the "thorny oyster," is solid red. It could only be gathered by experienced divers. So, this shell was more desired and traded by the Chimú.

Uses and Meanings of Shells

Spondylus shells were used in many ways in Andean culture. They came as whole shells, pieces, or ground powder. This material was used to create detailed ornaments, tools, and goods for nobles and gods. Shell pieces have been found as decorations for body ornaments and as beads for jewelry. The image to the right shows a Chimú collar made of cotton, red Spondylus beads, and black stone beads.

Representing wealth and power, the shell was ground into powder. An official called the Fonga Sigde would spread it before the Chimor king. This created a "red carpet" for the ruler. Shells were also used to decorate buildings.

Found in the tombs of nobles, these items were often buried with the dead. They also played a role in special ceremonies. Because they came from the sea, shells were valued for their link to water and good crops. They were used as offerings in fields to help crops grow. The Chimú also placed shells in water sources like wells and springs. This was done to bring rain to their fields, especially during dry times.

The meaning of the Spondylus shell is linked to its physical traits. Its unique shape connected it to divine power. The spines on the outside of Spondylus shells linked them to strength and protection. Because of its shape and red, blood-like color, the shell often stood for death and special ceremonies. It was also linked to female body parts. Known as the "daughter of the sea," the Spondylus shell was also connected to women.

Spondylus has special sense organs, like sensitive eyes. Andean cultures linked these to extra protection. The shell is sensitive to water temperature changes and thrives in warmer waters. It was thought to have powers to predict the future. Its movements are linked to El Niño weather. So, its presence was seen as a sign of disaster.

Also, Spondylus can be poisonous at certain times of the year. This is called Paralytic shellfish poisoning (PSP). Twice a year, the mollusk's tissue contains substances toxic to humans. This is caused by poisonous algae the mollusks eat. During these months, the shells were offered to weather and fertility gods as "food for the gods." It was thought only gods were powerful enough to eat the mollusk's flesh. Eating small amounts might cause muscle weakness or a feeling of happiness. But larger amounts could lead to paralysis and death. Because of these effects, Spondylus was a symbol of spiritual connection. It was seen as a bridge between the physical and spirit worlds.

Diving for Shells

Even though shell workshops and artifacts are common in Chimor, the Spondylus shell comes from the warm waters of Ecuador. Getting the shell was hard work and took a lot of time. It required skilled divers to free dive up to 50 meters deep. They had to pry the shells off rocks.

The difficult task of shell diving is shown in many Andean artworks. These include bowls, earspools, and textiles. Many images show a boat with sailors holding ropes attached to divers in the water. Stone weights hung from the divers as they gathered shells. Pictures of Spondylus often show their spiky parts. The image to the right shows a Chimú earspool. It was made from gold-copper and silver alloys. It shows a shell diving scene. The top part shows a boat with large sails. Birds are at the top of the piece. Four divers swim below the boat near spiky, egg-shaped shells.

Parts of ciudadelas, which were large compounds for kings and important people, were used to store shell artifacts. The buildings themselves showed the treasures of the sea. "Los Buceadores (the Divers)," a carving in Chan Chan in Ciudadela Uhle, shows two figures in a reed boat. One holds a paddle. Another pair of shell divers are below the boat, connected by ropes. The carving also shows a net-like shape and spiky figures representing shells.

Making and Trading Shells

Most of what we know about shell-working in the Andes comes from archaeological finds and old writings. Spondylus is found in many places across Peru. It has been discovered in burial sites and with the remains of shell workshops. The shell objects are very similar, and the work was technical. This suggests that Spondylus production was done by skilled craftspeople. Many collections of Spondylus items have objects from different stages of shell production. These include whole shells, pieces, finished items, and waste from making them.

One workshop, thought to be maintained by the Chimú, was found at Túcume in the Lambayeque Region of Peru. Archaeologist Daniel Sandweiss found it. Dating back to around 1390-1480 A.D., the workshop had small rooms. It showed proof of Spondylus bead production. Shell waste from all stages, from cut pieces to finished beads, was found. Stone tools used to work the shell were also dug up.

While many archaeological sources show a lot of shell-working, there is little proof of how Spondylus moved from Ecuador to workshops in Chan Chan. Archaeological records show that Chimor was an important trade center. Shells often traveled long distances to reach the Chimor empire. The trade of Spondylus was key to the Chimú's growing political power and economy. The shell was seen as a special material. The Chimor's control over this luxury trade helped them gain political power. It also helped them show their rulers were legitimate. Unlike the Inca Empire, the Chimú did not try to expand their control of the Spondylus trade by conquering nearby states. Instead, they used their existing access to the trade as a religious and financial reason for their power.

Little is known about how Spondylus was obtained and traded. Scholars have suggested different ways Spondylus moved. The mollusk was likely traded by independent merchants or through state-controlled long-distance trade. It moved from north to south. One of the first accounts of Spondylus trade comes from Spanish colonist Francisco Xerez. He was with Francisco Pizarro. He described a raft of luxury goods, like textiles, emeralds, and gold and silver items. These were to be traded for Spondylus shells.

Researchers also disagree on how shells were transported. They debate if they were moved by sea or land. Images in Andean pottery and carvings show llama caravans carrying shells. This suggests that some shell transportation was done over land.

Textiles and Clothing

Spinning is the process of twisting fibers together to make a long, continuous thread. This was done using a tool called a spindle. The spindle was a small stick, often thinner at both ends. It was used with a tortera or piruro, which acted as a weight. The spindle was spun, pulling fibers from a rueca (where the fiber was held). Fibers were quickly twisted between the thumb and index fingers to interlock them, creating a long thread. Once enough thread was made, threads were woven together in different ways to create fabrics.

The Chimú decorated their fabrics with brocades (raised patterns), embroidery, double fabrics, and painted designs. Sometimes textiles were decorated with feathers and gold or silver plates. Tropical feathers used in these textiles show that they traded over long distances. Colored dyes came from plants like those containing tannin, mole, or walnut. Minerals like clay or aluminum were also used. Dyes also came from animals like cochineal.

Their clothes were made from the wool of four animals: the guanaco, llama, alpaca, and vicuna. They also used different types of cotton that grew naturally in seven colors. Chimú clothing included loincloths, sleeveless shirts (with or without fringes), small ponchos, and tunics.

Most Chimú textiles were made from alpaca wool and cotton. Based on how the fibers were spun and their colors, it's likely that all the fibers were spun beforehand. They were probably imported from one place.

Chimú Pottery

The Chimú civilization is known for its beautiful and detailed metalwork. It was one of the most advanced before the arrival of Europeans. Chimú pottery had two main uses: containers for daily home use and ceremonial items for offerings at burials. Everyday pottery was not highly finished. But funeral ceramics showed more artistic skill.

The main features of Chimú pottery were small sculptures. They also made molded and shaped pottery for ceremonies or daily use. Ceramics were usually stained black, but there were some other colors. Lighter colored pottery was made in smaller amounts. The shiny look was achieved by rubbing the pottery with a polished rock. Many animals, fruits, people, and mystical creatures were shown on Chimú ceramics.

Archaeological findings suggest that Chimor grew from the remains of the Moche. Early Chimú pottery looked somewhat like Moche pottery. Their ceramics are all black. Their work in precious metals is very detailed and complex.

Metalwork Skills

Metalworking became very important in the later Chimú periods. The Chimú worked with metals like gold, silver, and copper. Some Chimú artisans worked in metal workshops. These workshops were divided into sections for different metal treatments. These included plating, gold work, stamping, lost-wax casting, and embossing wooden molds. These techniques created many objects. These included cups, knives, containers, figurines, bracelets, pins, and crowns. They used arsenic to make metals harder after casting.

Large-scale metal melting happened at a group of workshops at Cerro de los Cemetarios. The process started with ore from mines or a river. This ore was heated to very high temperatures and then cooled. This resulted in small, round pieces of copper (prills) mixed with slag (other useless materials). The prills were then taken out by crushing the slag. They were then melted together to form ingots. These ingots were shaped into various items.

The Chimú also shaped metals by hammering them. The image on the right shows a silver Chimú beaker made this way. Chimú metalsmiths did this with simple tools and a single sheet of gold. The artist would first carve a wooden mold. Then they would carefully hammer the very thin sheet of gold around the wooden base.

Copper is found naturally on the coast. But most of it came from the highlands, about three days away. Since most copper was imported, most metal objects made were likely very small. These pieces, like wires, needles, digging stick points, tweezers, and personal ornaments, were consistently small. They were useful objects made of copper or copper bronze. The Tumi is a famous Chimú metalwork. They also made beautiful ceremonial costumes of gold compounds. These included feathered headdresses, earrings, necklaces, bracelets, and chest plates.

Chimú Religion

Gods and Beliefs

In Pacasmayo, the Moon god (Si or Shi) was the most important god. It was believed to be more powerful than the Sun. This was because it appeared both at night and during the day. It also controlled the weather and how crops grew. People offered animals and birds to the Moon. They also offered their own children on piles of colored cottons with fruit and chicha (a drink). They believed the sacrificed children would become gods. These children were usually about five years old.

The Chimú also worshipped Mars (Nor) and Earth (Ghisa) gods. They worshipped the Sun (Jiang) and the Sea (Ni) gods. Jiang was linked to stones called alaec-pong (cacique stone). These stones were believed to be ancestors of the people in that area and sons of the Sun. The Chimú offered maize flour and red ochre to Ni. This was for protection against drowning and for good fish catches.

Several groups of stars were also important. Two stars in Orion's Belt were seen as messengers of the Moon. The constellation Fur (the Pleiades) was used to figure out the year. It was believed to watch over the crops.

Each area had local shrines that varied in importance. These shrines, called huacas, were also found in other parts of Peru. They had a sacred object of worship (macyaec) with a related legend and religious practices.

Offerings and Discoveries In 1997, archaeologists found about 200 skeletons on the beach at Punta Lobos, Peru. These were likely fishermen. Some suggest they might have been killed as a thank you to the sea god Ni. This could have happened after the Chimú conquered the fishermen's fertile seaside valley in 1350 A.D.

Tombs in the Huaca of the Moon contained the remains of six or seven teenagers, aged 13–14. Nine tombs belonged to children.

In 2011, archaeologists found human and animal skeletons in the village of Huanchaco. After years of digging, they identified over 140 human skeletons. These were children between 6 and 15 years old. They also found over 200 llama skeletons. Anthropologist Haagen Klaus thinks the Chimú might have turned to offering children when adult offerings were not enough. This was to stop heavy rain and floods caused by El Niño.

Chimú Architecture

Different types of palaces and large sites showed who the rulers were compared to common people. At Chan Chan, there are ten large, walled areas called ciudadelas. These were royal compounds. They are surrounded by adobe walls that are nine meters high. This makes the ciudadela look like a fortress.

Most of the Chimú population (about 26,000 people) lived in barrios on the city's outer edge. These had many single-family homes with a kitchen, work space, places for animals, and storage.

Ciudadelas often have U-shaped rooms. These rooms have three walls, a raised floor, and often a courtyard. There could be as many as 15 in one palace. In the early Chimú period, these U-shaped areas were in key places. They helped control the flow of supplies from storerooms. They are thought to have been used to remember how supplies were given out. Over time, more U-shaped structures were built. They became more grouped together and further from resource access routes.

The architecture of rural sites also showed a system of social classes. They had similar parts, making them like smaller ciudadelas with rural administrative jobs. Most of these sites had smaller walls. Many audiencias were the main part of these buildings. These were used to limit access to certain areas. They were often found at important points.

Chan Chan does not show a clear overall plan. The city center has six main types of buildings:

- Ten ciudadelas - these were citadels or palace fortresses.

- Homes for Chan Chan's non-royal wealthy people.

- Artisan homes and workshops spread throughout the city.

- Four huacas or temple mounds.

- U-shaped audiencias or courts.

- SIAR or small irregular rooms. These were probably where most of the people lived.

|

See also

In Spanish: Reino Chimú para niños

In Spanish: Reino Chimú para niños

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |