Chinese space program facts for kids

The space program of the People's Republic of China involves all the activities in outer space carried out by China. China's space journey began in the 1950s. With help from the Soviet Union, China started developing its first ballistic missiles and rockets. This was a response to threats they felt from the United States and later, the Soviet Union.

Inspired by the Soviet Sputnik 1 and American Explorer 1 satellite launches in 1957 and 1958, China launched its own first satellite, Dong Fang Hong 1, in April 1970. It was carried by a Long March 1 rocket. This made China the fifth nation to put a satellite into orbit.

Today, China has one of the busiest space programs in the world. It uses the Long March rocket family for launches. China also has four spaceports: Jiuquan, Taiyuan, Xichang, and Wenchang. Each year, China performs a very high number of orbital launches.

Its satellite fleet includes many satellites for communications, navigation, Earth observation, and science. China's activities have grown from low Earth orbit to the Moon and Mars. China is one of only three countries, along with the United States and Russia, that can send humans into space independently.

Most of China's space activities are managed by the China National Space Administration (CNSA). The People's Liberation Army Strategic Support Force also plays a role, guiding the astronaut corps and the Chinese Deep Space Network. Key programs include the China Manned Space Program, BeiDou Navigation Satellite System, Chinese Lunar Exploration Program, Gaofen Observation, and Planetary Exploration of China. China has completed several important missions, such as Chang'e-4, Chang'e-5, Chang’e-6, Tianwen-1, and building the Tiangong space station.

Contents

History of China's Space Journey

Starting Small: The Early Years (1950s-1970s)

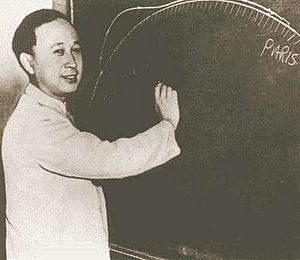

China's space program began with missile research in the 1950s. After its founding in 1949, China wanted missile technology to strengthen its defense during the Cold War. In 1955, Qian Xuesen, a famous rocket scientist, returned to China from the United States. He proposed developing China's missile program, which was quickly approved.

On October 8, 1956, China's first missile research institute was created. It had fewer than 200 staff, mostly recruited by Qian. This event is seen as the start of China's space program.

China began missile development by copying two Soviet R-2 missiles. These were secretly sent to China in December 1957. The Chinese version was called "1059." The target launch date was postponed because Soviet technical help was suddenly withdrawn due to the Sino-Soviet split. Meanwhile, China built its first missile test site in the Gobi desert. This site later became the famous Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center, China's first spaceport.

After the Soviet Union launched Sputnik 1 in 1957, Mao Zedong decided China should also have satellites. In May 1958, he approved Project 581. The goal was to launch a satellite by 1959 to celebrate the 10th anniversary of China's founding. This goal was too ambitious, so they decided to focus on sounding rockets first.

The program's first success was the launch of T-7M. This sounding rocket reached 8 km high on February 19, 1960. It was the first rocket developed by Chinese engineers. Mao Zedong praised this success. However, all Soviet help stopped after the 1960 Sino-Soviet split. Chinese scientists continued with very limited resources. Despite this, China successfully launched the first "missile 1059" on December 5, 1960. This missile was later renamed Dongfeng-1 (DF-1).

While copying the Soviet missile, Qian's team began developing Dongfeng-2 (DF-2). This was the first missile designed and built entirely by China. After an early failure, DF-2 had its first successful launch on June 29, 1964, in Jiuquan. This was a major step for China's missile development.

DF-2 had seven more successful launches. On October 27, 1966, an improved version, Dongfeng-2A, successfully launched and detonated a nuclear warhead. As China's missile industry grew, a new plan for carrier rockets and satellites was approved in 1965. This was Project 651. On January 30, 1970, China successfully tested the two-stage Dongfeng-4 (DF-4) missile. This missile showed important technologies like rocket staging and attitude control. The DF-4 was used to create the Long March 1 (LM-1 or CZ-1).

China's space program also benefited from the Third Front campaign. This campaign developed basic industries and defense in China's rugged interior. It prepared for possible invasions. Almost all new aerospace facilities in the late 1960s and early 1970s were part of this campaign. This included expanding Jiuquan and building the Xichang Satellite Launch Center and Taiyuan Satellite Launch Center.

On April 24, 1970, China launched the 173 kg Dong Fang Hong I satellite. It was carried by a Long March 1 rocket from Jiuquan. This was the heaviest first satellite launched by any nation. China's second satellite, the 221 kg ShiJian-1, was launched on March 3, 1971. It carried scientific instruments.

China also made small steps in human spaceflight. On July 19, 1964, a T-7A(S1) sounding rocket successfully launched and recovered a biological experiment with eight white mice. In 1967, Mao and Zhou Enlai decided China should start its own crewed space program. China's first spacecraft for humans was named Shuguang-1 in January 1968. The first crewed program, Project 714, aimed to send two astronauts into space by 1973. Nineteen astronauts were chosen. However, the program was canceled in the same year due to political issues.

While CZ-1 was being developed, work began on China's first long-range intercontinental ballistic missile, the Dongfeng-5 (DF-5). Its first test flight was in 1971. Its technology was used for two different Chinese medium-lift launch vehicles. One was Feng Bao 1 (FB-1), developed in Shanghai. The other was Long March 2 (CZ-2), developed in Beijing. Both used the same fuel as DF-5.

On July 26, 1975, FB-1 made its first successful flight. It put the 1107 kg Changkong-1 satellite into orbit. This was China's first payload heavier than 1 metric ton. Four months later, on November 26, CZ-2 successfully launched the FSW-0 No.1 recoverable satellite. It returned to Earth three days later. This made China the third country able to recover a satellite. FB-1 and CZ-2 later became the basis for the Long March rocket family: Long March 4 and Long March 2.

As part of the Third Front effort, a new space center was built in the mountains of Xichang in Sichuan province. This was Base 27. The Northern Missile Test Site was also upgraded in January 1976 to become the Base 25.

A New Era of Growth (Late 1970s-1980s)

After Mao's passing, Deng Xiaoping became China's new leader in 1978. Some projects were canceled, but others continued. The first Yuanwang-class space tracking ship was launched in 1979. The first full test of the DF-5 ICBM was on May 18, 1980. Its payload reached its target 9300 km away in the South Pacific. In 1982, Long March 2C (CZ-2C) had its first flight. This upgraded Long March 2 could carry 2500 kg to low Earth orbit (LEO). Long March 2C became a key rocket for China's space program.

As China focused on economic development, the need for communications satellites grew. The Chinese communications satellite program, Project 331, started on March 31, 1975. The first generation of China's own communication satellites was named Dong Fang Hong 2 (DFH-2). Launching these satellites to geostationary orbit was a big challenge.

The task was given to Long March 3 (CZ-3), China's most advanced launch vehicle in the 1980s. Long March 3 was based on Long March 2C but had an extra third stage. This stage was designed to send payloads to geosynchronous transfer orbit (GTO). Engineers chose an advanced cryogenic engine for the third stage, which uses liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen. This was challenging but had great potential. Development of this engine began in 1976 and finished in 1983. Xichang Satellite Launch Center was chosen as the launch site for Long March 3 because its low latitude helps with GTO launches.

On January 29, 1984, Long March 3 had its first flight from Xichang. It carried the first experimental DFH-2 satellite. The cryogenic third-stage engine failed to re-ignite, so the satellite ended up in a lower orbit. Engineers quickly found the problem and fixed it.

On April 8, 1984, Long March 3 launched again from Xichang. This time, it successfully put the second experimental DFH-2 satellite into the correct GTO. The satellite reached its final orbit on April 16. This made China the fifth country with independent geostationary satellite development and launch capability. On February 1, 1986, the first practical DFH-2 communications satellite was launched. This ended China's need for foreign communications satellites.

In the 1980s, human spaceflights became more common with the American Space Shuttle and Soviet space stations. China's canceled human spaceflight program was quietly revived. In March 1986, Project 863 was proposed by four scientists. Its goal was to boost advanced technologies, including human spaceflight. This project led to early studies of China's new human spaceflight program.

Commercial Launches and New Challenges (1990s)

After the success of Long March 3, China announced a commercial launch program for international customers in 1985. This led to a decade of commercial launches in the 1990s. China Great Wall Industry Corporation (CGWIC) provided the launch service. The first contract was signed with AsiaSat in January 1989 to launch AsiaSat 1.

On April 7, 1990, a Long March 3 rocket successfully launched AsiaSat 1. This successful first commercial launch gave China a good start in the global market.

However, Long March 3's 1,500 kg payload capacity was not enough for new communication satellites, which often weighed over 2,500 kg. To solve this, China introduced Long March 2E (CZ-2E). This was China's first rocket with strap-on boosters. It could carry up to 3,000 kg to GTO. Development of Long March 2E began in November 1988. Engineers built all the hardware in a record 18 months. On September 16, 1990, Long March 2E had a successful test flight.

But an accident happened during a highly anticipated launch on March 22, 1992. All engines shut down unexpectedly after ignition. The rocket could not lift off. An investigation found that small aluminum scraps caused a short circuit. The rocket and payload were saved. Less than five months later, on August 14, a new Long March 2E successfully launched the Optus satellite.

In June 1993, the China Aerospace Corporation was founded and also named the China National Space Administration (CNSA). An improved Long March 3, called Long March 3A, began service in 1994. However, on February 15, 1996, during the first flight of the even more improved Long March 3B, the rocket crashed 22 seconds after launch. This accident caused fatalities and injuries, making it a very difficult event for China's space program.

The two launch failures within a few months hurt the reputation of the Long March rockets. China's commercial launch service faced canceled orders and higher insurance costs. In response, the Chinese space industry started a major quality improvement effort. A strict quality management system was put in place. This greatly increased the success rate. From October 20, 1996, to August 16, 2011, China achieved 102 successful space launches in a row. On August 20, 1997, Long March 3B had its first successful flight, launching the 3,770 kg Agila-2 satellite. It could carry up to 5,000 kg to GTO. Long March 3B became China's most powerful rocket for nearly 20 years. In 1998, the China Aerospace Corporation was reorganized. Its administrative part became part of the Commission for Science, Technology and Industry for National Defense, keeping the CNSA title. The rest split into China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation (CASC) and China Aerospace Science and Industry Corporation (CASIC) in 1999.

While Long March rockets tried to regain the commercial market, political pressure from the United States increased. In 1998, the U.S. accused some companies of sharing technology that helped China's missile program. This led to the Cox Report, which further accused China of stealing sensitive technologies. In 1999, the U.S. Congress passed a law that restricted satellites with U.S.-made parts from being launched on Chinese rockets. This stopped commercial cooperation between China and the U.S. The last American satellites launched by a Chinese rocket were two Iridium satellites on June 12, 1999. This regulation largely excluded Long March rockets from the international commercial launch market.

Despite commercial challenges, China's space program made a huge breakthrough. On November 20, 1999, Shenzhou 1, the first uncrewed Shenzhou spacecraft for human spaceflight, was successfully launched. It was carried by a Long March 2F rocket from Jiuquan. The spacecraft orbited Earth 14 times and landed safely in Inner Mongolia. This marked the full success of China's first Shenzhou test flight. After this, the previously secret China Manned Space Program (CMS) was made public. CMS, approved in 1992 as Project 921, had three goals: crewed spacecraft launch and return, a space laboratory for short missions, and a long-term modular space station. Fourteen astronauts were chosen for the People's Liberation Army Astronaut Corps and began training.

Major Steps: Shenzhou and Chang'e (2000s)

Since the early 2000s, China's economy grew quickly, leading to more investment in space. In November 2000, the Chinese government released its first white paper, China's Space Activities. It outlined goals for the next decade, including:

- Building an Earth observation system.

- Creating an independent satellite broadcasting and telecommunications system.

- Establishing an independent satellite navigation system.

- Improving China's launch vehicles.

- Achieving human spaceflight and setting up a research and testing system for it.

- Developing space science and exploring outer space.

The independent satellite navigation system mentioned was Beidou. Its development began in 1983. The "first step" of BeiDou, with two satellites, was launched in October and December 2000. This experimental system, BeiDou-1, offered basic services in and around China. China then started building BeiDou-2, a more advanced system for the Asia-Pacific region. The first two BeiDou-2 satellites launched in 2007 and 2009.

Another major goal was human spaceflight. The China Manned Space Program continued to grow. From January 2001 to January 2003, China conducted three uncrewed Shenzhou test flights. These validated all systems for human spaceflight. Shenzhou 4, launched in December 2002, was the last uncrewed rehearsal.

On October 15, 2003, the first Chinese astronaut, Yang Liwei, launched aboard Shenzhou-5. It was carried by a Long March 2F rocket from Jiuquan. The spacecraft entered orbit ten minutes after launch, making Yang the first Chinese person in space. After more than 21 hours and 14 orbits, the spacecraft landed safely. Yang walked out of the capsule himself. The success of Shenzhou 5 was widely celebrated. It marked China as the third country to achieve independent human spaceflight.

The China Manned Space Program continued its progress. In 2005, two Chinese astronauts, Fei Junlong and Nie Haisheng, completed China's first "multi-person and multi-day" spaceflight on Shenzhou-6. On September 25, 2008, Shenzhou-7 launched with three astronauts: Zhai Zhigang, Liu Boming, and Jing Haipeng. During this flight, Zhai and Liu performed China's first spacewalk in orbit.

Around the same time, China began preparing for space exploration beyond Earth, starting with the Moon. Research on Moon exploration began in 1994. The 2000 white paper listed the Moon as the main target for China's deep space exploration. In January 2004, the Chinese Moon orbiting program was approved. It later became the Chinese Lunar Exploration Program (CLEP). CLEP was divided into three phases: "Orbiting, Landing, Returning." All were to be done by robotic probes.

On October 24, 2007, the first lunar orbiter, Chang'e 1, was successfully launched by a Long March 3A rocket. It entered Moon orbit on November 7. It then surveyed the Moon and produced China's first lunar map. On March 1, 2009, Chang'e-1 made a controlled landing on the Moon's surface, ending its mission. Chang'e-1 was China's first deep space mission. It was recognized as a major milestone for China's space program.

In other areas, China made progress in commercial launches despite U.S. sanctions. In April 2005, China launched the APStar 6 communications satellite for a French company. In May 2007, China launched the NigComSat-1 satellite. This was the first time China provided full service, from satellite manufacturing to launch, for international customers.

Growth and Breakthroughs (2010s)

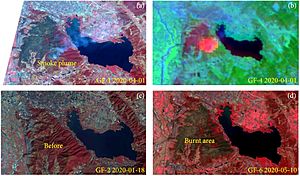

From 2000 to 2010, China's economy grew rapidly. This led to more demand for high-resolution Earth observation systems. To reduce reliance on foreign data, China started the China High-resolution Earth Observation System program, known as Gaofen, in May 2010. Its goal is to create an all-day, all-weather Earth observation system. The first Gaofen satellite, Gaofen 1, launched on April 26, 2013. More satellites followed. As of late 2022, over 30 Gaofen satellites are operating.

The BeiDou Navigation Satellite System grew very quickly. Five BeiDou-2 navigation satellites launched in 2010 alone. By late 2012, the BeiDou-2 system, with 14 satellites, was completed. It began providing service to the Asia-Pacific region. Construction of the more advanced BeiDou-3 started in November 2017. China launched 24 satellites into medium Earth orbit, 3 into inclined geosynchronous orbit, and 3 into geostationary orbit within three years. The final BeiDou-3 satellite launched on June 23, 2020. On July 31, 2020, the BeiDou-3 system was declared complete and operational worldwide. It combines navigation and communication functions. It is now one of the four main global navigation satellite systems recognized by the United Nations.

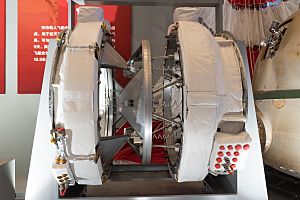

The China Manned Space Program continued to make breakthroughs in human spaceflight technologies. China worked with Russia on docking mechanisms for space stations. In late 2009, the China Manned Space Agency began training astronauts on how to dock spacecraft. To practice, China launched an 8000 kg target vehicle, Tiangong 1, in 2011. This was followed by the uncrewed Shenzhou 8. The two spacecraft performed China's first automatic rendezvous and docking on November 3, 2011. This confirmed the docking procedures. About nine months later, in June 2012, Tiangong 1 completed the first manual rendezvous and docking with Shenzhou 9. This crewed spacecraft carried Jing Haipeng, Liu Wang, and China's first female astronaut, Liu Yang. The successes of Shenzhou 8 and 9 showed China's progress in space rendezvous and docking. Tiangong 1 was later docked with Shenzhou 10, carrying astronauts Nie Haisheng, Zhang Xiaoguang, and Wang Yaping. They did scientific experiments, gave lectures to students, and performed more docking tests. They returned safely after 15 days in space. These missions showed China's mastery of basic human spaceflight technologies.

While Tiangong 1 was a space station prototype, its functions were limited. Tiangong 2, China's first real space laboratory, launched on September 15, 2016. It was visited by the Shenzhou 11 crew a month later. Two astronauts, Jing Haipeng and Chen Dong, stayed in Tiangong 2 for about 30 days. This broke China's record for the longest human spaceflight mission. They carried out various experiments. In April 2017, China's first cargo spacecraft, Tianzhou 1, docked with Tiangong 2. It completed multiple in-orbit fuel refueling tests.

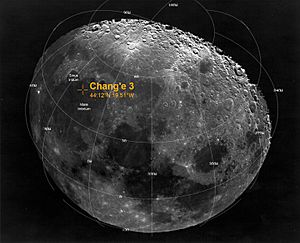

For deep space explorations, after completing the "Orbiting" goal in 2007, CLEP prepared for the "Landing" phase. China's second lunar probe, Chang'e 2, launched on October 1, 2010. It used a direct path to the Moon for the first time. It imaged the Sinus Iridum region for future landing missions. On December 2, 2013, a Long March 3B rocket launched Chang'e 3, China's first lunar lander, to the Moon. On December 14, Chang'e 3 successfully landed in the Sinus Iridum region. This made China the third country to soft-land on an extraterrestrial body. A day later, the Yutu rover was deployed. It began its survey, achieving the "landing and roving" goal for the second phase of CLEP.

China also made its first attempt at interplanetary exploration. Yinghuo-1, China's first Mars orbiter, launched with the Russian Fobos-Grunt spacecraft in November 2011. Yinghuo-1 was a small project in cooperation with Russia. However, the Fobos-Grunt probe failed to start its main engine and was stranded in low Earth orbit. Two months later, Fobos-Grunt and Yinghuo-1 burned up in Earth's atmosphere. Although Yinghuo-1 failed, it brought together talented people for interplanetary research. On December 13, 2012, the Chinese lunar probe Chang'e 2, on an extended mission, flew by asteroid Toutatis. This made it China's first interplanetary probe. In 2016, China's first independent Mars mission was approved. This mission aimed to achieve Mars orbiting, landing, and roving in one attempt in 2020.

While China made progress in many areas, the Long March rockets, the foundation of China's space program, were also changing. Since the 1970s, Long March rockets used toxic fuels. To improve this, China began studying new, cleaner fuels in 1986. In 2000, development of a 120-ton rocket engine burning LOX and kerosene was approved. This engine, named YF-100, was certified in 2012. On September 20, 2015, the Long March 6, a small rocket using one YF-100 engine, had its first successful flight. On June 25, 2016, the medium-lift Long March 7, with six YF-100 engines, also had a successful first flight. This increased China's maximum LEO payload capacity to 13.5 tons. These successes marked the start of the "new generation of Long March rockets" with cleaner, more efficient engines.

The first launch of Long March 7 was also the first from Wenchang Space Launch Site in Hainan Province. Wenchang, built starting in September 2009, is China's newest and most advanced spaceport. Rockets launched from Wenchang can carry more payload due to its low latitude. Also, rocket debris falls into the ocean, making it safer. Wenchang's coastal location allows larger rockets to be delivered by sea.

The biggest breakthrough was the Long March 5, China's first heavy-lift launch vehicle. Its development began in 1986 and was approved in the mid-2000s. It used 247 new technologies. The 57-meter tall Long March 5 has a 5-meter-diameter core stage burning LH2/LOX and four 3.35-meter-diameter side boosters burning kerosene/LOX. With a launch mass of 869 metric tons, it can lift up to 25 tons to LEO and 14 tons to GTO. This made it China's most powerful rocket. After a successful first flight in late 2016, the second launch of Long March 5 on July 2, 2017, failed. This was a major setback. The Long March 5 was grounded until the problem was fixed, delaying many planned missions.

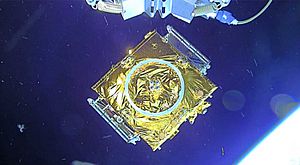

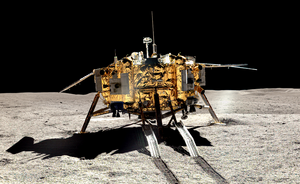

Despite the Long March 5's uncertain future, China made history in space exploration with existing rockets. The far side of the Moon had never been explored up close due to communication issues. China's Chang'e 4 mission in 2019 changed this. To solve the communication problem, China launched Queqiao, a relay satellite orbiting around the Earth–Moon L2 Lagrangian point, in May 2018. On December 8, 2018, Chang'e 4 launched and entered lunar orbit. On January 3, 2019, Chang'e 4 successfully soft-landed in the Von Kármán (lunar crater) on the far side of the Moon. It sent back the first close-up image of the far side. A rover named Yutu-2 was deployed hours later. Chang'e-4 made China the first country to successfully soft-land and rove on the far side of the Moon. The project team received the IAF World Space Award in 2020.

Other notable events during this period include:

- August 2016: China launched the world's first quantum communications satellite, Mozi.

- June 2017: The first Chinese X-ray astronomy satellite, Huiyan, launched.

- August 2017: Chinese and ESA astronauts participated in a joint training in China for the first time.

- 2018: China performed more orbital launches than any other country.

- June 5, 2019: China conducted its first Sea Launch with Long March 11 in the Yellow Sea.

- July 25, 2019: Chinese private company i-Space successfully conducted an orbital launch with its Hyperbola-1 rocket.

As the 2010s ended, the Long March 5 rocket had a highly anticipated return-to-flight mission on December 27, 2019. After being grounded for 908 days, it successfully launched Shijian-20, China's heaviest satellite, into orbit. The successful return of Long March 5 opened the way for many world-class space projects.

Recent Achievements (2020-Present)

The flight-proven Long March 5 greatly expanded China's space capabilities. Since 2020, with Long March 5, China's space program has made huge progress. It completed some of the most challenging missions in space exploration history.

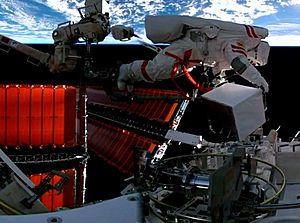

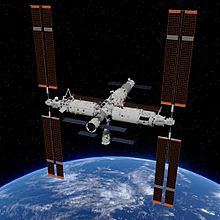

The "Third Step" of the China Manned Space Program began in 2020. Long March 5B, a variant of Long March 5, had its first successful flight on May 5, 2020. Its large payload capacity allowed it to deliver Chinese space station modules. On April 29, 2021, the 22-tonne Tianhe core module of the space station launched successfully. This marked the start of building the China Space Station, also known as Tiangong. This was followed by many human spaceflight missions. A month later, China launched Tianzhou 2, the first cargo mission to the space station. On June 17, Shenzhou 12, the first crewed mission to the Chinese Space Station, launched. The crew docked with Tianhe and entered the module. They lived and worked on the station for three months, did two spacewalks, and returned safely on September 17, 2021. This broke China's record for the longest human spaceflight mission. About a month later, the Shenzhou 13 crew launched to the station. Astronauts Zhai Zhigang, Wang Yaping, and Ye Guangfu completed China's first long-duration spaceflight mission, lasting over 180 days. They returned safely on April 16, 2022. Astronaut Wang Yaping became the first Chinese female to perform a spacewalk during this mission.

Starting in May 2022, the China Manned Space Program entered the space station assembly phase. On June 5, 2022, Shenzhou 14 launched and docked with the Tianhe core module. The crew was expected to welcome two more space station modules. On July 24, the third Long March 5B rocket launched the 23.2 t Wentian laboratory module. This was China's largest and heaviest spacecraft. It docked with the space station less than 20 hours later. On September 30, the Wentian module was moved to a different port. On October 31, the Mengtian laboratory module, the third and final module, launched and docked with the space station. On November 3, the 'T-shape' China Space Station was completed. On November 29, Shenzhou 15 launched and docked. Astronauts Fei Junlong, Deng Qingming, and Zhang Lu were welcomed by the Shenzhou-14 crew. This was the first time two Chinese crews met in space, starting continuous Chinese astronaut presence in space.

The third phase of the Chinese Lunar Exploration Program also moved forward in 2020. As preparation, China conducted the Chang'e 5-T1 mission in 2014. This showed China's ability to return a spacecraft from lunar orbit to Earth safely. This paved the way for a lunar sample return mission. However, the failure of the second Long March 5 mission delayed the original plan. The mission was postponed until Long March 5's successful return-to-flight in late 2019. On November 24, 2020, the sample return mission, Chang'e 5, launched. The Long March 5 rocket launched the 8.2 t spacecraft. It entered lunar orbit on November 28. The lander touched down near Mons Rümker on December 1 and began collecting samples. Two days later, on December 3, the ascent vehicle took off from the lunar surface and entered lunar orbit. This was China's first launch from an extraterrestrial body. On December 6, the ascent vehicle docked with the orbiter in lunar orbit and transferred the sample container. This was the first robotic rendezvous and docking in lunar orbit in history. On December 13, the orbiter and return module headed back to Earth. The return capsule landed safely in Inner Mongolia on December 17, completing the mission.

On December 19, 2020, CNSA announced that Chang'e-5 retrieved 1,731 grams of samples from the Moon. Chang'e-5 achieved many milestones: China's first lunar sampling, first liftoff from an extraterrestrial body, first automated rendezvous and docking in lunar orbit by any nation, and the first spacecraft to re-enter Earth's atmosphere at high speed with samples. Its success completed the "Orbiting, Landing, Returning" goal of CLEP.

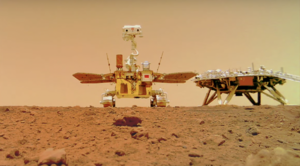

Before Chang'e-5, China's first Mars probe had already departed. Since the Mars mission was approved in 2016, China developed needed technologies, including a deep space network and atmospheric entry systems. Long March 5 was ready after its successful return-to-flight. On April 24, 2020, CNSA announced the Planetary Exploration of China program. China's first independent Mars mission was named Tianwen-1. On July 23, 2020, Tianwen-1 launched successfully. The spacecraft, with an orbiter, lander, and rover, aimed to achieve orbiting, landing, and roving on Mars in one mission. This ambitious mission was widely watched.

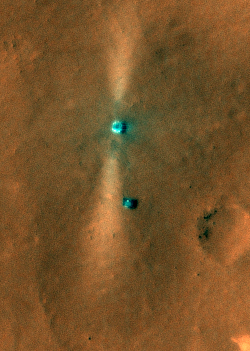

After a seven-month journey, on February 10, 2021, Tianwen-1 entered Mars orbit. The orbiter's instruments were activated and began surveying Mars for a landing site. On April 24, CNSA announced that the Mars rover was named Zhurong, after the ancient Chinese god of fire.

On May 15, 2021, Tianwen-1 began its landing process. The lander separated and moved towards Mars' atmosphere. Three hours later, the landing module went through a dangerous nine-minute atmospheric entry. At 7:18 am, the lander successfully touched down in southern Utopia Planitia. On May 25, the Zhurong rover drove onto the Martian surface. On June 11, CNSA released the first high-resolution images from the Zhurong rover. Tianwen-1 completed orbiting, landing, and roving on Mars in one attempt. This made China the second nation to land and drive a Mars rover after the United States. The Tianwen-1 team received the IAF World Space Award in 2022.

On March 13, 2024, China attempted to launch two spacecraft, DRO-A and DRO-B, into a distant retrograde orbit around the Moon. This mission, managed by the Chinese Academy of Sciences, aimed to test technologies for a future lunar navigation system. However, due to an upper stage malfunction, the mission initially failed to reach its intended orbit and remained stranded in low Earth orbit. Rescue attempts were made, and their orbit was significantly raised. They appear to have succeeded in reaching their desired orbit.

On March 20, 2024, China launched its relay satellite, Queqiao-2, into lunar orbit, along with two mini satellites, Tiandu 1 and 2. Queqiao-2 will relay communications for the Chang'e 6 (far side of the Moon), Chang'e 7, and Chang'e 8 (Lunar south pole region) spacecraft. Tiandu 1 and 2 will test technologies for a future lunar navigation and positioning system. All three probes successfully entered lunar orbit on March 24, 2024. Tiandu-1 and 2 separated in lunar orbit on April 3, 2024.

China sent Chang'e 6 on May 3, 2024. This mission conducted the first lunar sample return from the Apollo Basin on the far side of the Moon. This was China's second lunar sample return mission. It also carried the Chinese Jinchan rover to perform infrared spectroscopy of the lunar surface and image the Chang'e 6 lander. The lander-ascender-rover combination separated from the orbiter and returner before landing on June 1, 2024. The ascender launched back to lunar orbit on June 3, 2024, carrying collected samples. It then completed another robotic rendezvous and docking in lunar orbit. The sample container was transferred to the returner, which landed in Inner Mongolia on June 25, 2024. This completed China's far side extraterrestrial sample return mission. After dropping off the samples, the Chang'e 6 orbiter was successfully captured by the Sun-Earth L2 Lagrange point on September 9, 2024.

Future Plans

According to a 2022 government white paper, China plans more human spaceflight, lunar, and planetary exploration missions, including:

- Launching the Xuntian Space Telescope.

- The Chang'e 7 mission to land precisely in the Moon's polar region. It will include a "hopping detector" to explore shadowed areas.

- The Chang'e 8 lunar polar mission to test using resources found on the Moon. This will help set up the International Lunar Research Station.

- The Tianwen-2 mission to collect samples from near-Earth asteroids and study main-belt comets.

- The Tianwen-3 mission, using two launches, to bring samples back from Mars.

- The Tianwen-4 mission to explore the Jupiter system and Callisto. A probe to fly by Uranus will be attached to the Jupiter probe.

China has also started the crewed lunar landing phase of its lunar exploration program. It aims to land Chinese astronauts on the Moon by 2030. A new crewed carrier rocket (Long March 10), new generation crew spacecraft, crewed lunar lander, lunar EVA spacesuit, lunar rover, and other equipment are being developed.

CNSA's Tianwen-2 launched in May 2025. It will explore the co-orbital near-Earth asteroid 469219 Kamoʻoalewa and the active asteroid 311P/PanSTARRS. It will also collect samples from Kamo'oalewa.

China's Space Program and the World

Working with Other Countries

China aims to improve satellite information pathways as part of its Belt and Road Initiative. China is an appealing partner for space cooperation for other developing countries. It launches their satellites at a lower cost and often provides financial support.

For African countries, China has committed to using space technology to improve cooperation. It plans to create centers for Africa-China cooperation on satellite remote sensing. African countries are increasingly working with China on satellite launches and training. As of 2022, China has launched satellites for Ethiopia, Nigeria, Algeria, Sudan, and Egypt.

China and Namibia jointly operate the China Telemetry, Tracking, and Command Station. It was set up in 2001 in Swakopmund, Namibia. This station tracks Chinese satellites and space missions.

China and Brazil have successfully worked together in space. They have developed and launched Earth monitoring satellites. As of 2023, they have jointly developed six China-Brazil Earth Resource Satellites. These projects have helped both countries access satellite imagery and promoted remote sensing research. This cooperation is a unique example of two developing countries working together in space.

Dual-Use Technologies and Space

China is a member of the United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space. It has signed almost all United Nations treaties and agreements on space. The United States government has been hesitant about American companies using Chinese launch services. This is due to concerns about civilian technology possibly being used for military purposes by countries like North Korea, Iran, or Syria. Financial penalties have been applied to Chinese space companies many times.

NASA's Policy Excluding Chinese Affiliates

The Cox Report, released in 1999, claimed that China stole design information for advanced thermonuclear weapons. In 2011, the U.S. Congress passed a law. It prohibited NASA researchers from working with Chinese citizens linked to a Chinese state company without FBI approval. It also restricted using NASA funds to host Chinese visitors. In March 2013, another law barred Chinese nationals from entering NASA facilities without a waiver.

This U.S. exclusion policy began with claims that American companies' technical information for commercial satellites helped improve Chinese intercontinental ballistic missile technology. This was made worse in 2007 when China destroyed an old weather satellite in low Earth orbit to test an anti-satellite (ASAT) missile. The debris created added to space junk, risking other nations' space assets. The U.S. also worries about China using dual-use space technology for harmful purposes.

China's response to this policy has been to open its space station to the world. It welcomes scientists from all countries. American scientists have also protested NASA conferences that exclude Chinese nationals.

How China's Space Program is Organized

Initially, China's space program was part of the People's Liberation Army. In the 1990s, it was reorganized to be more like Western defense industries.

The China National Space Administration (CNSA) is now responsible for launches. The Long March rocket is made by the China Academy of Launch Vehicle Technology. Satellites are produced by the China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation. These are state-owned companies. However, the Chinese government intends for them to act as independent design bureaus.

Universities and Institutes

The space program works closely with several universities and institutes, including:

- College of Aerospace Science and Engineering, National University of Defense Technology

- School of Astronautics, Beihang University

- School of Aerospace, Tsinghua University

- School of Astronautics, Northwestern Polytechnical University

- School of Aeronautics and Astronautics, Zhejiang University

- Institute of Aerospace Science and Technology, Shanghai Jiaotong University

- College of Aeronautics, Harbin Institute of Technology

- School of Automation Science and Electrical Engineering, Beihang University

Space Cities

- Dongfeng Space City

- Beijing Space City

- Wenchang Space City

- Shanghai Space City

- Yantai Space City

- Guizhou Aerospace Industrial Park

Suborbital Launch Sites

- Nanhui: First successful launch of a T-7M sounding rocket on February 19, 1960.

- Base 603: Also known as Guangde Launch Site. The first successful flight of a biological experimental sounding rocket carrying eight white mice was launched and recovered on July 19, 1964.

Satellite Launch Centers

China has 6 satellite launch centers/sites:

- Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center (JSLC)

- Taiyuan Satellite Launch Center (TSLC)

- Xichang Satellite Launch Center (XSLC)

- Wenchang Spacecraft Launch Site (administered by Xichang SLC)

- Wenchang Commercial Space Launch Site (administered by HICAL)

- Haiyang Oriental Aerospace Port (administered by Taiyuan SLC)

Monitoring and Control Centers

- Beijing Aerospace Command and Control Center (BACCC)

- Xi'an Satellite Control Center (XSCC)

- Fleet of six Yuanwang-class space tracking ships.

- Data relay satellites: Tianlian I and Tianlian II systems. These improve communication time and data transfer for spacecraft.

- Chinese Deep Space Network: Includes radio antennas in Beijing, Shanghai, Kunming, and Ürümqi.

Domestic Tracking Stations

- New integrated land-based space monitoring and control network stations, forming a large triangle with Kashi, Jiamusi, and Sanya.

- Weinan Station

- Changchun Station

- Qingdao Station

- Zhanyi Station

- Nanhai Station

- Tianshan Station

- Xiamen Station

- Lushan Station

- Jiamusi Station

- Dongfeng Station

- Hetian Station

Overseas Tracking Stations

- Tarawa Station, Kiribati

- Malindi Station, Kenya

- Swakopmund tracking station, Namibia

- China Satellite Launch and Tracking Control General tracking hub at Espacio Lejano Station in Neuquén Province, Argentina.

- Shared space tracking facilities with France, Brazil, Sweden, and Australia.

Crewed Landing Sites

- Siziwang Banner

Key Spaceflight Programs

Project 714: Early Human Spaceflight

In 1967, Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai decided China should not be left behind in the Space Race. They started the top-secret Project 714. It aimed to put two people into space by 1973 using the Shuguang spacecraft. Nineteen pilots were chosen in March 1971. The program was officially canceled in May 1972 due to economic and political reasons.

A short-lived second crewed program was announced in 1978. It was based on successful landing technology from FSW satellites. This program was canceled in 1980. Some believe it was mainly for propaganda.

Project 863: Advanced Technology Push

A new crewed space program was proposed in March 1986 as Astronautics plan 863-2. This included a crewed spacecraft (Project 863–204) to carry astronauts to a space station (Project 863–205). Astronauts in training were shown to the media. This project eventually led to the 1992 Project 921.

China Manned Space Program (Project 921)

Shenzhou Spacecraft

In 1992, the first phase of Project 921 was approved and funded. This plan was to launch a crewed spacecraft. The Shenzhou program had four uncrewed test flights. The first was Shenzhou 1 on November 20, 1999. Shenzhou 2 launched in January 2001 with test animals. Shenzhou 3 and Shenzhou 4 launched in 2002 with test dummies. Then came the successful Shenzhou 5 on October 15, 2003. This was China's first crewed mission, carrying Yang Liwei into orbit for 21 hours. This made China the third nation to launch a human into orbit. Shenzhou 6 followed two years later, completing the first phase of Project 921. Missions are launched on the Long March 2F rocket from the Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center. The China Manned Space Agency (CMSA) provides support for these missions.

Space Laboratory Development

The second phase of Project 921 began with Shenzhou 7, China's first spacewalk mission. Two crewed missions were planned for China's first space laboratory. China designed the Shenzhou spacecraft with docking technologies compatible with the International Space Station (ISS). On September 29, 2011, China launched Tiangong 1. This module was the first step to testing technology for a planned space station.

On October 31, 2011, a Long March 2F rocket launched the uncrewed Shenzhou 8. It docked twice with the Tiangong 1 module. The Shenzhou 9 craft launched on June 16, 2012, with a crew of 3. It successfully docked with Tiangong-1 on June 18, 2012. This was China's first crewed spacecraft docking. Another crewed mission, Shenzhou 10, launched on June 11, 2013.

A second space lab, Tiangong 2, launched on September 15, 2016. It weighed 8,600 kg. Shenzhou 11 launched and met with Tiangong 2 in October 2016. The Tiangong 2 carried various scientific instruments and experiments. It also had the world's first in-space cold atomic fountain clock.

Building the Space Station

A larger, permanent space station is the third and final phase of Project 921. This will be a modular design, eventually weighing around 60 tons. It was completed in 2022. The first section, Tianhe core module, launched on April 29, 2021. It was first visited by the Shenzhou 12 crew on June 17, 2021. The Chinese space station was completed in 2022 and became fully operational in 2023.

Lunar Exploration Program

In January 2004, China formally began its uncrewed Moon exploration project. This project has three phases: orbiting the Moon, landing, and returning samples.

On December 14, 2005, it was reported that a program for uncrewed lunar landings would begin in 2007. A program to return uncrewed space vehicles from the Moon would start in 2012. A crewed Moon landing was planned after that.

On June 22, 2006, Long Lehao, deputy chief architect of the lunar probe project, set 2024 as the date for China's first moonwalk.

In September 2010, it was announced that China planned to send a person to the Moon by 2025. China also hoped to bring a Moon rock sample back to Earth in 2017.

On December 14, 2013, China's Chang'e 3 became the first object to soft-land on the Moon since 1976.

On May 20, 2018, the Queqiao relay satellite launched from Xichang. It took 24 days to reach its orbit around the Moon's L2 point. This was the first lunar relay satellite placed in this location.

On January 3, 2019, Chang'e 4 made the first-ever soft landing on the Moon's far side. The rover could send data back to Earth using the Queqiao satellite. Landing and data transmission were major achievements for human space exploration.

On November 23, 2020, China launched the Chang'e 5 Moon mission. It returned to Earth carrying lunar samples on December 16, 2020. Only two nations, the United States and the former Soviet Union, had ever returned materials from the Moon before.

China sent Chang'e 6 on May 3, 2024. It conducted the first lunar sample return from the far side of the Moon. This was China's second lunar sample return mission.

Mission to Mars and Beyond

In 2006, the Chief Designer of the Shenzhou spacecraft said that space programs aim to enable humans to work normally in space and prepare for future exploration of Mars, Saturn, and beyond.

Sun Laiyan, administrator of the China National Space Administration, said on July 20, 2006, that China would start deep space exploration focusing on Mars over the next five years. In April 2020, the Planetary Exploration of China program was announced. It aims to explore planets in the Solar System, starting with Mars, then expanding to include asteroids and comets, Jupiter, and more.

The first mission of the program, Tianwen-1 Mars exploration, began on July 23, 2020. A spacecraft, with an orbiter, lander, and the rover, launched by a Long March 5 rocket from Wenchang. Tianwen-1 entered Mars orbit in February 2021. The lander and Zhurong rover successfully soft-landed on May 14, 2021.

Space-Based Solar Power

Chinese interest in space-based solar power began in the 1990s. By 2013, it was a national goal. The roadmap included:

- 2020: Industrial testing of in-orbit construction and wireless transmissions.

- 2025: First 100kW SPS demonstration in LEO.

- 2035: 100MW SPS with electricity generating capacity.

- 2050: First commercial SPS system in GEO.

In 2015, the CAST team won a design competition with their Multi-Rotary Joint concept. In 2016, Lt Gen. Zhang Yulin suggested China would start using Earth-Moon space for industrial development. The goal would be to build space-based solar power satellites to beam energy back to Earth.

In June 2021, Chinese officials confirmed plans for a geostationary solar power station by 2050. A small-scale electricity generation test was planned for 2022, followed by a megawatt-level orbital power station by 2030. The gigawatt-level geostationary station will require over 10,000 tonnes of infrastructure.

Launchers and Projects

Launch Vehicles

Active or Under Development

- Air-Launched SLV: Can place a 50 kg payload to 500 km SSO.

- Ceres-1: Small-lift solid-fueled launch vehicle from a private company.

- Gravity-1: Medium-lift sea-launched solid fuel launch vehicle under development.

- Hyperbola-1: Small-lift solid-fueled launch vehicle from a private company.

- Hyperbola-3: Medium-lift liquid-fueled (methalox) launch vehicle with reusable first stage (VTVL) from a private company, under development.

- Jielong 3: Small to medium-lift solid fueled launch vehicle, currently in service.

- Kaituozhe-1A.

- Kuaizhou: Quick-reaction small-lift solid fuel launch vehicle.

- Lijian-1: Small to medium-lift solid fuel launch vehicle, currently in service.

- Lijian-2: Medium-lift liquid fuel (kerolox) launch vehicle with reusable first stage, under development.

- CZ-2E(A): For launching Chinese space station modules. Payload capacity up to 14 tons in LEO.

- CZ-2F/G: Modified CZ-2F without escape tower, for robotic missions like Shenzhou cargo and space laboratory modules. Payload capacity up to 11.2 tons in LEO.

- CZ-3B(A): More powerful Long March rockets with larger liquid propellant strap-on motors. Payload capacity up to 13 tons in LEO.

- CZ-3C: Combines CZ-3B core with two boosters from CZ-2E.

- Long March 4C.

- CZ-5: Heavy-lift hydrolox launch vehicle (with kerolox boosters).

- CZ-5B: Variant of the CZ-5 for low Earth orbit payloads (up to 25 tonnes to LEO).

- CZ-6: Small-lift kerolox LV with short launch preparation, low cost, and high reliability. For small satellites up to 500 kg to 700 km SSO.

- CZ-7: Medium-lift kerolox launch vehicle for resupply missions to the Tiangong space station.

- CZ-8: Medium-lift launch vehicle mainly for launching payloads to SSO orbits.

- CZ-9: Super heavy-lift launch vehicle with a LEO lift capability of 150 tonnes, under development (planned to be fully reusable).

- CZ-10: Crew-rated super-heavy launch vehicle for crewed lunar missions, under development.

- CZ-10A: Crew-rated medium-lift launch vehicle for launching the next-generation crewed spacecraft to LEOs with reusable first stage, under development.

- CZ-11: Small-lift solid fuel quick-response launch vehicle.

- Pallas-1: Reusable (1st stage) medium-lift liquid fuel (kerolox) launch vehicle by a private firm, under development.

- Project 921-3 Reusable launch vehicle: Current project of a reusable shuttle system.

- Tengyun: Another current project of a two-wing-staged reusable shuttle system.

- Reusable spaceplane: Reusable vertically launched spaceplane with wings that lands on a runway, currently in service (similar to the US X-37B).

- Tianlong 2: Medium-lift kerolox launch vehicle from a private firm (in service).

- Tianlong 3: Medium to heavy-lift kerolox launch vehicle with reusable first stage from a private firm, under development.

- Zhuque-2: Medium-lift liquid fuel (methalox) launch vehicle by a private firm, currently in service (first methane-fueled rocket in the world to reach space and orbit with payload).

- Zhuque-3: Medium to heavy-lift methalox launch vehicle by a private firm with reusable first stage, under development.

Cancelled/Retired

- CZ-1D: Based on a CZ-1 but with a new second stage.

- Project 869: Reusable shuttle system with Tianjiao-1 or Chang Cheng-1 (Great Wall-1) orbiters. A project from the 1980s-1990s.

Satellites and Science Missions

- Space-Based ASAT System: Small and nano-satellites developed by the Small Satellite Research Institute.

- The Double Star Mission: Two satellites launched in 2003 and 2004, with ESA, to study Earth's magnetosphere.

- Earth observation, remote sensing or reconnaissance satellites series: CBERS, Dongfanghong program, Fanhui Shi Weixing, Yaogan, and Ziyuan 3.

- Tianlian I telecommunication satellite.

- Tianlian II: Next generation data relay satellite (DRS) system.

- Beidou navigation system: Or Compass Navigation Satellite System, composed of 60 to 70 satellites.

- Astrophysics research: Includes the world's largest Solar Space Telescope and Project 973 Space Hard X-Ray Modulation Telescope.

- Chinese Deep Space Network: With the completion of the FAST, the world's largest single dish radio antenna of 500 m in Guizhou.

- A Deep Impact-style mission to test redirecting an asteroid or comet.

Space Exploration

Crewed Low Earth Orbit Program

- Project 921-1: Shenzhou spacecraft.

- Tiangong: First three crewed Chinese Space Laboratories.

- Project 921-2: Permanent crewed modular Chinese Space Station.

- Tianzhou: Robotic cargo vessel to resupply the Chinese Space Station.

- Next-generation crewed spacecraft: Upgraded version of the Shenzhou spacecraft to resupply the Chinese Space Station and return cargo.

- Project 921-11 – X-11 reusable spacecraft for Project 921-2 Space Station.

- Tianjiao-1 or Chang Cheng-1 (Great Wall-1): Winged spaceplane orbiters of Project 869 reusable shuttle system (1980s-1990s).

- Shenlong: Winged spaceplane orbiter of current Project 921-3 reusable shuttle system.

- Tengyun: Winged spaceplane orbiter in another current project of a two-wing-staged reusable shuttle system.

- HTS Maglev Launch Assist Space Shuttle: Winged spaceplane orbiter in another current shuttle project.

Chinese Lunar Exploration Program

- First phase: Chang'e 1 and Chang'e 2 – launched in 2007 and 2010.

- Second phase: Chang'e 3 and Chang'e 4 – launched in 2013 and 2018.

- Third phase: Chang'e 5-T1 (completed in 2014) and Chang'e 5 – (completed in 2020).

- Fourth phase: Chang'e 6 (sample-return from lunar far-side in May-June 2024), Chang'e 7 and Chang'e 8 – will explore the south pole for natural resources; may 3D-print a structure using regolith.

- Crewed mission: By the year 2030, crewed lunar missions using the next-generation crewed spacecraft and the crewed lunar lander.

Deep Space Exploration Program

China's first deep space probe, the Yinghuo-1 orbiter, launched in November 2011 with the joint Fobos-Grunt mission with Russia. However, the rocket failed to leave Earth orbit.

In 2018, Chinese researchers proposed a deep space exploration roadmap. It aims to explore Mars, an asteroid, Jupiter, and further targets between 2020 and 2030. Current and upcoming robotic missions include:

- Chinese Deep Space Network: Relay satellites for deep-space communication and exploration support.

- Tianwen-1: Launched on July 23, 2020, and arrived at Mars on February 10, 2021. Mission includes an orbiter, a deployable camera, a lander, and the Zhurong rover.

- Tianwen-2: Launched on May 29, 2025. Mission goals include asteroid flyby observations, global remote sensing, robotic landing, and sample return.

- Interstellar Express: Targeting launch around 2024–2025 for Interstellar Heliosphere Probe-1 (IHP-1) and around 2025–2026 for Interstellar Heliosphere Probe-2 (IHP-2). Objectives include exploring the heliosphere and interstellar space. They aim to be the first non-NASA probes to leave the Solar System.

- Mars Sample Return Mission: Planned for launch around 2028–2030. Goals include in-situ topography and soil analysis, deep interior investigations, and sample return. The plan is for two launches in November 2028.

- Jupiter System orbiter: Mission goals include orbital exploration of Jupiter and its four largest moons (focusing on Callisto). It will study the magnetohydrodynamics in the Jupiter system and investigate Jupiter's atmosphere and moons.

- A fly-by of Uranus is planned as part of the 2029-2030 Tianwen-4 mission. The Uranus fly-by probe will separate from the Jupiter orbiter and proceed to Uranus in the 2040s.

|

See also

In Spanish: Programa espacial chino para niños

In Spanish: Programa espacial chino para niños

- Beihang University

- China and weapons of mass destruction

- Two Bombs, One Satellite

- Chinese women in space

- Harbin Institute of Technology

- French space program

- List of human spaceflights to the Tiangong space station

| DeHart Hubbard |

| Wilma Rudolph |

| Jesse Owens |

| Jackie Joyner-Kersee |

| Major Taylor |