Cornwall Iron Furnace facts for kids

|

Cornwall Iron Furnace

|

|

Main building at Cornwall Iron Furnace

|

|

| Location | Rexmont Rd. and Boyd St., Cornwall, Pennsylvania |

|---|---|

| Area | 175 acres (71 ha) |

| Built | 1742, shutdown 1883 |

| Architect | Peter Grubb |

| NRHP reference No. | 66000671 |

Quick facts for kids Significant dates |

|

| Added to NRHP | November 13, 1966 |

| Designated NHLD | November 3, 1966 |

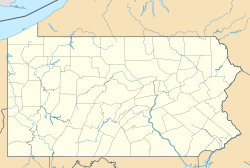

Cornwall Iron Furnace is a special historic place in Cornwall, Lebanon County, Pennsylvania. It is managed by the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. This furnace was a very important place for making iron in Pennsylvania from 1742 until it closed in 1883.

The furnace, its support buildings, and the nearby community have been kept as a historical site and museum. This helps us see what industrial life was like in Lebanon County long ago. It is the only complete old-style iron furnace that used charcoal for fuel, still in its original spot in North and South America. Peter Grubb started Cornwall Furnace in 1742. During the American Revolution, his sons, Curtis and Peter Jr., ran it. They supplied many weapons to George Washington's army. After the Revolution, Robert Coleman bought Cornwall Furnace. He became the first person in Pennsylvania to become a millionaire. In 1932, the furnace and its land were given to the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania.

What is Cornwall Iron Furnace?

Cornwall Iron Furnace was one of many ironworks built in Pennsylvania between 1716 and 1776. During the time of Colonial Pennsylvania, there were many places making iron. These included blast furnaces, forges, and mills for shaping metal.

The furnaces at Cornwall used two main types of technology over time. Peter Grubb was born around 1702. He moved to what is now Lebanon County in 1734. He bought about 300 acres of land that had a lot of magnetite, which is a type of iron ore. Grubb also saw that his land had other things needed to make iron. These included many trees for making charcoal, running water to power the bellows, and plenty of limestone. Limestone was needed to help clean the iron during the melting process.

Grubb's plans were also helped because the magnetite at Cornwall was very close to the surface. He decided to start an iron business. He built an "iron plantation," which was a whole community centered around making iron. These places were usually far from farms and deep in the mountains of Pennsylvania. Grubb first built a bloomery, which was a simpler furnace. Later, he built a more modern charcoal-fired blast furnace. He also built homes and other buildings for his workers. He named his operation Cornwall because his father, John Grubb, came from Cornwall, UK.

Cornwall Iron Furnace fit well with the farming economy of the Thirteen Colonies. Iron was needed to make tools, nails, and weapons. Great Britain did not want the colonies to make their own goods. However, England could not make enough iron for itself or the colonies. In fact, England had to buy iron from Sweden.

Peter Grubb was more of a builder than an iron master. In 1745, he rented the ironworks to a group called Cury and Company for 25 years. He then went back to Wilmington. The company kept the furnace running. After Peter died in 1754, his sons, Curtis and Peter Jr., took over. The brothers ran the furnace very well from 1765 until the late 1780s. Curtis lived at Cornwall Furnace and managed it. Around 1773, he built the first part of the large house that is still there today. Peter Jr. ran a forge at Hopewell. There, he turned the pig iron from the furnace into more valuable bar iron.

The ironworks were very important suppliers during the American Revolutionary War. George Washington even visited to see how things were going. Sadly for the Grubb family, they lost control of the furnace after Curtis got married in 1783. Most of the Grubb family's property slowly went to Robert Coleman. He fully owned it by 1798. Coleman's son, William, became the manager of Cornwall Furnace and lived in the mansion. In 1865, the Colemans updated the mansion into the large 29-room house known as Buckingham Mansion today.

The Iron Act

The Iron Act was a law passed in 1750 by the British. It was meant to help the American colonies produce raw materials like pig iron. However, it also tried to stop them from making finished iron goods. Existing factories could continue, but new ones for certain processes were not allowed.

How a Bloomery Works

The first furnace Peter Grubb built at Cornwall Iron Furnace was a bloomery. He built it in 1737 to see if his iron ore was good enough to sell. This was a cheap way to test the market without building a more expensive blast furnace.

A bloomery is like a very large blacksmith's fireplace. It has a pit or chimney with walls made of heat-resistant materials like earth, clay, or stone. At Cornwall, sandstone was used. Near the bottom, one or more clay pipes, called tuyeres, let air into the furnace. This air could come from natural wind or from bellows. An opening at the bottom could be used to take out the iron, or the bloomery could be tipped over.

Before using the bloomery, charcoal and iron ore must be ready. Charcoal is made by heating wood to create a pure carbon fuel. The ore is broken into small pieces and "roasted" in a fire to remove any water. Any large dirt pieces in the ore are crushed and removed. Old slag (waste material) from previous iron batches could also be broken up and put back into the bloomery.

To operate, the bloomery is first heated with burning charcoal. Once hot, iron ore and more charcoal are added from the top, usually in equal amounts. Inside, carbon monoxide from the burning charcoal changes the iron oxides in the ore into metal iron. This happens without melting the ore, so the bloomery works at lower temperatures. The goal is to make pure iron that is easy to shape. So, the temperature and the amount of charcoal must be carefully controlled. This stops the iron from absorbing too much carbon, which would make it hard to shape. Limestone could also be added, about 10% of the ore's weight. This acts as a flux to help remove impurities.

Small pieces of iron fall to the bottom and stick together to form a spongy mass called a bloom. The bottom also fills with melted slag, which is waste material mixed with impurities. Because the bloom is full of holes and slag, it must be reheated and hammered. This hammering pushes the melted slag out. Iron treated this way is called wrought iron, which is very pure iron.

How a Blast Furnace Works

In 1742, Grubb replaced his bloomery with a 30-foot-high charcoal-fired cold blast furnace. This blast furnace burned much hotter than the bloomery. It could melt the iron ore into liquid pig iron (also called "charcoal iron").

A blast furnace works because unwanted silicon and other impurities are lighter than the melted iron. Grubb's furnace was a tall, chimney-like structure lined with special heat-resistant bricks. Charcoal, limestone, and iron ore were poured in at the top. Air was blown in through pipes near the bottom. This "blast" helps the charcoal burn, creating a chemical reaction. This reaction turns the iron oxide into pure metal iron, which sinks to the bottom.

The temperature in the furnace is usually about 1500°C (2732°F). This heat also breaks down limestone into calcium oxide and carbon dioxide. The calcium oxide then reacts with impurities in the iron, forming a slag that floats on top of the iron.

The pig iron made by the blast furnace is not useful for most things because it has a lot of carbon (about 4-5%). This makes it very brittle. Some pig iron is used to make cast iron goods. For other uses, the carbon content needs to be lowered. In the past, this was done in a finery forge. Later, new methods like puddling were used.

Today, this is done by shooting high-pressure oxygen into a special rotating container with the pig iron. Some of the carbon turns into carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide. This also cleans out other impurities. The container spins, and the cleaned pig iron can be separated from the waste. Before the mid-1800s, pig iron was turned into wrought iron, which is very pure. If steel was needed, pure iron was heated with charcoal to make blister steel (with about 1-2% carbon). This could be further cleaned using the crucible technique, but steel was too expensive for large-scale use. However, with the Bessemer process in the late 1850s, steel production greatly increased. By the late 1800s, most iron was turned into steel before being used.

Making Charcoal

The blast furnaces at Cornwall Furnace needed a huge amount of charcoal to keep them hot and make iron steadily. Making charcoal became a big job itself. Hardwood trees were cut down, dried, stacked, and burned in large pits, about 30 to 40 feet wide. A collier carefully stacked the wood around a chimney. The stack was covered with leaves and dirt and set on fire in the middle. The fires were allowed to smolder for ten to fourteen days. The collier watched them carefully, day and night. They made sure enough heat was made to remove water and other things from the wood without burning it all up. Wood was only turned into charcoal right before it was needed, so it would not get wet and become useless. The demand for charcoal was so great that Cornwall Furnace used an entire acre of wood every day to make charcoal.

Working at the Furnace

The furnace ran twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week, only stopping for repairs. Cornwall Iron Furnace could make 24 tons of iron each week. A large waterwheel powered the bellows, which blew air into the furnace. Carts carried charcoal between the coal barn and the furnace under a roof to keep it dry. Other wagons hauled ore from the mine to the top of the furnace on the hillside. Workers then moved the charcoal and ore into the furnace by hand.

The guttermen worked at the bottom of the furnace. They raked the cooling sand and dug channels for the melted pig iron. Then, they stacked the bars of pig iron outside. The working conditions were very tough. Temperatures inside the casting house could reach as high as 160°F (71°C).

Such a big and difficult iron and charcoal making operation needed many strong workers. The furnace alone needed about sixty people working around the clock in twelve-hour shifts. The ironworks also had a company clerk, many teamsters (drivers), woodcutters, colliers, farmers, and household servants. There was a big difference between the rich owners and the poor workers. Workers lived in small homes and worked very hard for low pay. The owners and managers lived in large mansions with many servants.

There were three groups of workers at Cornwall Iron Furnace: free labor, indentured servants, and slaves. Slavery was legal in Pennsylvania until it slowly ended starting in 1780. The furnace managers had some trouble with the indentured servants. These workers, who were not skilled, came from Germany, England, and Ireland. Many of them worked at Cornwall for a short time before running away.

The Coleman Family's Story

Robert Coleman

Robert Coleman started as a clerk in Philadelphia. He then became a bookkeeper at Cornwall Iron Furnace. He eventually became the first millionaire in Pennsylvania.

Coleman arrived in Philadelphia from Ireland in 1764. After working as a clerk and bookkeeper, he leased Salford Forge near Norristown in 1773. He quickly made a lot of money by making cannonballs and shot at Salford and Elizabeth Furnaces. He then used his profits to buy a two-thirds share of Elizabeth Furnace, parts of Cornwall and the Upper and Lower Hopewell Furnaces, and ownership of Speedwell Forge. Soon, Coleman built Colebrook Furnace, bought the rest of Elizabeth Furnace, and gained 80% ownership of Cornwall Furnace and the nearby ore mines. His business deals and the money he made from them helped him become the first millionaire in Pennsylvania's history.

George Dawson Coleman

George Dawson Coleman was Robert Coleman's grandson. George and his brother, Robert, controlled much of the Coleman iron fortune. George gained more control of the ore mines at Cornwall. He was able to try out iron furnaces that used anthracite coal instead of coke. He also put money into the growing railroad system. He built houses, a school, and a church for his employees. People in his community loved him, and he served several times in the Pennsylvania State Legislature. Several churches built by the Coleman family are still in the area today.

George oversaw many improvements at Cornwall Iron Furnace. The bellows were replaced with "blowing tubs." These were air pumps powered by pistons that held compressed air and forced it into the furnaces. The waterwheel was replaced by a steam engine in 1841. The furnace stack was rebuilt in the 1850s.

The Colemans handed over direct management of Cornwall Iron Furnace to John Reynolds in 1848. He was the father of John F. Reynolds, who became a general and was the first Union General to die at the Battle of Gettysburg. The elder Reynolds managed the furnace until he died in 1853.

Robert Habersham Coleman

Robert Habersham Coleman was the fourth and last generation of the Coleman family to own the furnace. He closed the facility in 1883 and opened new ones for the company. In 1881, when he took over his family's business, Coleman was worth about seven million dollars. By 1889, he was thought to be worth thirty million dollars. However, by 1893, his fortune was gone. One of his homes, Cornwall Hall, showed how the "king" of Cornwall rose, became famous, and then declined during America's Gilded Age.

Why the Furnace Closed

Cornwall Iron Furnace became old-fashioned by the 1880s. New ways of making steel, like the Bessemer and open-hearth processes, came along. Also, charcoal was replaced by coke and anthracite coal as fuel. New iron deposits were found in Minnesota near Lake Superior. Modern factories were built in Pittsburgh, Steelton, and Bethlehem. All these changes led to the end of iron production in Cornwall.

Cornwall Furnace did not make a profit in its last ten years. The last owner, Robert Habersham Coleman, closed it on February 11, 1883. In 1932, Margaret Coleman Buckingham gave the furnace and its buildings to the state. Since then, they have been fixed up and are open for people to visit.

See also

- Cast Iron

- Iron

- Ironworks

- Ewiger Jäger— Cornwall Iron Furnace is the site of a ghostly legend of the Wild Hunt.

- List of National Historic Landmarks in Pennsylvania

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Lebanon County, Pennsylvania