Early European modern humans facts for kids

Early European modern humans (EEMH), also known as Cro-Magnons, were the first modern humans (Homo sapiens) to live in Europe. They arrived from Western Asia and may have continuously lived there as early as 56,800 years ago. These early humans met and mixed with the Neanderthals, who were already living in Europe and Western Asia. Neanderthals died out between 40,000 and 35,000 years ago.

The first group of modern humans in Europe, around 45,000-40,000 years ago, did not leave their genes to people living today. However, a second group, starting about 37,000 years ago, became the main ancestors of all later early European modern humans. Their genes are still found in people in Europe today.

Early European modern humans created amazing Upper Palaeolithic cultures. The first big one was the Aurignacian culture. By 30,000 years ago, the Gravettian culture took its place. During the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), a very cold period peaking 21,000 years ago, the Gravettian culture split. It became the Epi-Gravettian in the east and the Solutrean in the west. As Europe got warmer, the Solutrean culture changed into the Magdalenian around 20,000 years ago. These people then spread out and repopulated Europe. Later, the Magdalenian and Epi-Gravettian cultures were replaced by Mesolithic cultures. This happened as large game animals became scarce and the last ice age ended.

EEMH looked similar to people today, but they were stronger and had bigger brains. They also had wider faces, more noticeable brow ridges, and larger teeth. The very first EEMH even had some features like Neanderthals. The earliest EEMH probably had darker skin. Lighter skin started to become more common around 30,000 years ago due to natural selection.

Before the Last Glacial Maximum, EEMH lived in small groups. They were tall, similar to people today. They also had long trade routes, stretching up to 900 kilometers (about 560 miles). They hunted large animals. EEMH populations were much larger than Neanderthal populations. This might be because EEMH had more children. For both groups, people usually lived less than 40 years.

After the Last Glacial Maximum, more people lived in smaller areas. Communities traveled less often but over longer distances. With more mouths to feed and fewer large animals, they started hunting smaller animals or fishing more. They also used game drive systems to hunt whole herds at once. EEMH used spears, spear-throwers, and harpoons. They might have also used throwing sticks and had Palaeolithic dogs. EEMH likely built temporary huts when they moved around. Gravettian people on the East European Plain famously made large huts from mammoth bones.

EEMH were famous for their art. This included cave paintings, Venus figurines, and animal statues. They also made geometric patterns. They might have decorated their bodies with ochre crayons. Perhaps they even had tattoos, scarification, or piercings. The meaning of their art is still a mystery. However, many believe EEMH practiced shamanism. In this belief, cave art, especially human-animal hybrids, was very important. They also wore decorative beads and clothes made from plant fibers. These clothes were dyed with plant-based colors and might have shown a person's status symbols. For music, they made bone flutes and whistles. They might have also used bullroarers, rasps, and drums. They buried their dead, but only important people might have received a burial.

Contents

Discovering Early Humans

For a long time, people knew about ancient cultures. But they thought these were people from before the Great Flood mentioned in the Bible. After the idea of evolution became popular in the mid-1800s, scientists started studying EEMH more. Sadly, early studies were often influenced by scientific racism. They tried to link EEMH to certain modern European groups. These ideas were proven wrong by the mid-1900s. During the first wave feminism movement, some thought the Venus figurines showed a matriarchal religion (where women held power). But this idea mostly faded in academic circles by the 1970s.

When They Lived

When modern humans arrived in Europe, they met Neanderthals. Neanderthals had lived there for hundreds of thousands of years. In 2019, some scientists suggested that two 210,000-year-old skulls from Greece were modern humans. This would mean humans were in Europe much earlier than thought. But other scientists disagreed. Around 60,000 years ago, the climate became very unstable. Forests grew and shrank, replaced by open grasslands.

First Migrations

The earliest sign of modern humans in Europe is a set of teeth. They were found with stone tools in France. These date back to between 56,800 and 51,700 years ago. This shows humans were in Europe surprisingly early. Other early human fossils are from Bulgaria, Italy, and Britain. These date to about 45,000-43,000 years ago. It's not clear if they followed the Danube River or the Mediterranean coast. Around 45,000-44,000 years ago, the Proto-Aurignacian culture spread across Europe. This was the first widely recognized Upper Palaeolithic culture.

Later Stone Age Cultures

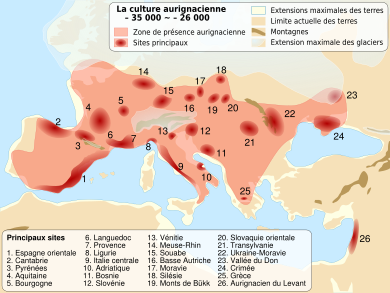

After 40,000 years ago, the Aurignacian culture developed. It quickly spread across Europe. This group of modern humans replaced Neanderthals. The Aurignacian culture lasted until about 29,000 years ago.

The Gravettian culture slowly replaced the Aurignacian. We don't know exactly where the Gravettian culture came from. But genetic evidence shows that some Aurignacian family lines continued. Around 37,000 years ago, a single group became the ancestors of all later early European modern humans. Europe then stayed genetically separate from the rest of the world for 23,000 years.

Around 29,000 years ago, the climate got much colder. This was the peak of the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) about 21,000 years ago. Huge glaciers covered much of northern Europe. Most of Europe became a polar desert. People could only live in certain areas. Two different cultures appeared: the Solutrean in Southwestern Europe and the Epi-Gravettian in the east. The Solutrean people invented new tools. The Epi-Gravettian people adapted older tools.

Glaciers started to melt around 20,000 years ago. The Solutrean culture changed into the Magdalenian. These people then spread across Western and Central Europe. Around 14,000 years ago, new genes from the Near East appeared in Europeans. This showed that Europe was no longer genetically isolated. As large animals became rarer, the Magdalenian and Epi-Gravettian cultures were replaced by Mesolithic cultures. This happened by the start of the Holocene period.

Europe was fully repopulated between 9,000 and 5,000 years ago. Genes from West European Hunter-Gatherers (WHG) are a big part of the European genome today. Also, genes from Ancient North Eurasians (ANE) and Caucasus Hunter-Gatherers (CHG) are present. Most modern Europeans have a mix of 40–60% WHG genes. Around 8,000 years ago, Neolithic farmers from the Near East spread across Europe. They brought farming and new genes. Around 4,500 years ago, people from the Yamnaya and Corded Ware cultures arrived from the eastern steppes. They brought the Bronze Age and the Proto-Indo-European language. This led to the genetic makeup of Europeans we see today.

How They Are Classified

EEMH were called "Cro-Magnons" in science until the 1990s. The name "Cro-Magnon" comes from five skeletons found in 1868 in France. They were discovered by accident while clearing land for a railway.

People had found ancient fossils and tools for decades before this. But they thought these were from people who lived before the biblical Great Flood. For example, a skeleton called the Red Lady of Paviland (who was actually a young man) was found in 1822. The scientist thought he was a Roman Briton. He thought the jewelry meant he was a woman or even a witch. Later, the idea that Earth's history was much older than the Bible suggested became popular.

After Charles Darwin's book On the Origin of Species in 1859, some scientists tried to divide humans into different "races." They used unreliable methods like measuring skulls. This continued into the 1900s. This was a continuation of Carl Linnaeus's system from 1735. He classified humans as Homo sapiens with different "subspecies" based on racist ideas. These ideas were then applied to ancient fossils like EEMH and Neanderthals.

Early ideas about EEMH often linked them to "superior" European races. Some thought they were tall, smart proto-Aryans from Scandinavia and Germany. These ideas fit with Nordicism and Pan-Germanism, which were popular before World War I. The Nazis later used these ideas to justify their actions in World War II. By the 1940s, these racist ideas in science started to disappear. This was partly because of the positivism movement, which aimed to remove bias from science. Also, the link between these ideas and Nazism made them unpopular.

How Many People Lived?

The start of the Upper Palaeolithic saw a big increase in Europe's human population. The number of people in Western Europe might have grown tenfold. Most people, both Neanderthals and modern humans, died before age 40. Few lived to be elderly. The population boom might have been due to more births.

A 2005 study estimated the population of Upper Palaeolithic Europe. It looked at how much land was inhabited. It also used population densities of modern Native American groups living in cold climates.

- From 40,000 to 30,000 years ago, the population was roughly 1,700–28,400 (average 4,400).

- From 30,000 to 22,000 years ago, it was roughly 1,900–30,600 (average 4,800).

- From 22,000 to 16,500 years ago, it was roughly 2,300–37,700 (average 5,900).

- From 16,500 to 11,500 years ago, it was roughly 11,300–72,600 (average 28,700).

After the Last Glacial Maximum, EEMH likely moved around less. They had higher population density. This is shown by shorter trade routes. It also suggests they faced more nutritional stress.

What They Looked Like

Physical Features

The average brain size for 28 early modern human skulls was about 1478 cubic centimeters (cc). For 13 EEMH, it was about 1514 cc. Today's humans average 1350 cc. So, EEMH had larger brains on average. Their brains had longer frontal lobes and taller occipital lobes. It's not clear if this meant any differences in how they thought.

EEMH looked similar to people today. They had a round braincase, a flat face, and a clear chin. However, their bones were thicker and stronger. The earliest EEMH often had features like Neanderthals. For example, some Aurignacian people had a slightly flattened skull and a noticeable bump at the back of the skull. These features became less common in later Gravettian people. Scientists think these were signs of mixing with Neanderthals that eventually disappeared.

In early Upper Palaeolithic Western Europe, men were about 176.2 cm (5 ft 9 in) tall on average. Women were about 162.9 cm (5 ft 4 in) tall. This is similar to modern Northern Europeans. Later, in the late Upper Palaeolithic, men averaged 165.6 cm (5 ft 5 in) and women 153.5 cm (5 ft 0 in). This is similar to pre-industrial humans. It's not clear why earlier EEMH were taller. It could be due to better diets from hunting large animals. Or it might be because taller people were more likely to be buried.

Scientists used to think EEMH had light skin, like modern Europeans. This was thought to help them get enough vitamin D from the weaker sun in the north. But genetic studies show that genes for lighter skin, hair, and eye color became common much later. One gene for lighter skin, KITLG, started to become more common around 30,000 years ago. Other genes for lighter skin and eye color, like blue eyes, appeared between 19,000 and 6,000 years ago.

Genetics

- Further information: Genetic history of Europe

Modern humans outside Africa came from a migration that happened around 65,000-55,000 years ago. Genetic analysis shows EEMH are closely related to Upper Palaeolithic East Asian groups. They split about 50,000 years ago.

Early genetic studies in 2014 found three main genetic lines in EEMH. These are also found in present-day Europeans. However, later studies in 2016 looked at even older European samples. They found that earlier EEMH (before 37,000 years ago) did not pass on their genes to people living today. These early groups were very diverse. But starting around 37,000 years ago, EEMH came from a single founding group. This group was genetically isolated from the rest of the world. All EEMH from this time onwards contributed to the genes of present-day Europeans.

Genetic evidence shows that early modern humans mixed with Neanderthals. Genes from Neanderthals entered the modern human gene pool about 65,000-47,000 years ago. This likely happened in Western Asia. In 2015, a 40,000-year-old human from Romania was found to have 6–9% Neanderthal DNA. This meant a Neanderthal ancestor was only four to six generations back. However, this group did not contribute much to the genes of later Europeans. This suggests that mixing with Neanderthals might have been common, but not all mixed groups survived. Over time, the amount of Neanderthal genes in humans decreased. This might mean these genes were not helpful for survival.

Recent studies in 2022 and 2023 have given us more details about the different groups of people in Europe. The earliest inhabitants (around 50,000 years ago) did not leave genes to modern people. A second group (around 45,000 years ago) was more related to East Asians. They also did not leave lasting genes. Then, a West-Eurasian group (around 40,000 years ago) expanded into Europe and Siberia. The ancestors of today's Western Hunter-Gatherers (WHGs) were linked to the Epi-Gravettian culture. They largely replaced people linked to the Magdalenian culture around 14,000 years ago.

Their Way of Life

There was a big change in technology when EEMH replaced Neanderthals. This led to the terms "Middle Palaeolithic" and "Upper Palaeolithic." The Upper Palaeolithic saw faster changes in tools and culture. This included making small stone tools, using bone and antler more, and creating art. They also had long-distance trade and better hunting tools. Magdalenian people made some of the most detailed art. They even decorated everyday objects.

Hunting and Gathering

Historically, studies often focused on men hunting big game. But female anthropologists later showed that women played a key role. They gathered plants and small game, which were more reliable food sources.

EEMH likely studied animal habits to find food. For example, large mammals gathered in certain seasons. There is much evidence that EEMH, especially in Western Europe after the LGM, herded large animals. They would drive them into natural traps like cliffs or dead-end valleys. This allowed them to kill whole herds efficiently. They timed these mass kills with animal migrations. This included red deer, horses, reindeer, and mammoths. They also ate fish, especially after the mid-Upper Palaeolithic.

After the LGM, Magdalenian people relied more on small animals, fish, and plants. This was because large game became scarce. People after the LGM often showed signs of poor nutrition. This included being shorter. This suggests they had to eat a wider range of less desirable foods to survive. In southwestern France, EEMH heavily depended on reindeer. They might have followed the herds. Epi-Gravettian groups usually focused on hunting one type of large game, like horses or bison. Human hunting, along with climate change, might have contributed to the extinction of large animals like mammoths and woolly rhinoceroses.

For weapons, EEMH made spearpoints from bone and antler. These materials were strong and less likely to shatter than stone. They attached these points to shafts to make javelins. Aurignacian people made diamond-shaped spearheads. By 30,000 years ago, spearheads had rounded bases. The spear-thrower was invented in Europe by the start of the LGM. This tool made spears fly farther and more accurately. A possible boomerang made of mammoth tusk was found in Poland. It dates to 23,000 years ago. Stone spearheads became common in the Solutrean period. Archery might have been invented then too, but clear evidence for bows comes later. Bone tools and long-range weapons like harpoons became very common in the Magdalenian period.

Society

Social System

Some early ideas suggested that prehistoric societies were led by women (matriarchies). This was because it was hard to track fathers in ancient times. This idea was later used by the first-wave feminism movement. They argued that women were powerful in early human society. They also saw the Venus figurines as evidence of a mother goddess religion. However, these ideas have largely been debated by archaeologists.

Looking at the archaeological record, drawings of women are much more common than men. The Venus figurines are common in the Gravettian period. But drawings of men are rare and debated. Most people who were buried (which might show high social status) were men. Also, the strength of bones in EEMH men and women was similar. This might mean that the division of labor between sexes, common in later societies, only became widespread later.

Trading

The Upper Palaeolithic shows signs of long-distance trade. Communities kept in touch over great distances. Early Upper Palaeolithic people moved around a lot. Gravettian groups often got raw materials from over 200 kilometers (124 miles) away. Some cultural practices, like making Venus figurines, spread 2000 kilometers (1240 miles) across Europe. Genetic evidence suggests that ideas, not people, moved between Europe and Siberia. At a 30,000-year-old site in Romania, shells from the Mediterranean Sea were found. These shells came from at least 900 kilometers (560 miles) away. This long-distance connection might have helped them survive during a changing climate.

After the LGM, people lived in smaller areas. This led to more local economies. But there is still some evidence of long-distance Magdalenian trade. For example, at Lascaux cave, a painting of a bull had traces of a mineral called hausmannite. This mineral is found 250 kilometers (155 miles) away in the Pyrenees. This suggests a local trade network for minerals. Also, Mediterranean and Atlantic seashells were found far inland. This shows a trade network along rivers in France, Germany, and Switzerland.

Housing

EEMH cave sites often show clear areas for different activities. There were places for fires, cooking, butchering, sleeping, and trash. EEMH were likely very mobile. They probably built temporary shelters like huts in open areas. Evidence of huts is usually found near a hearth (fireplace).

Magdalenian people were likely very mobile. They followed animal herds as they repopulated Europe. Many sites show they abandoned and revisited areas regularly. Rectangular stone-lined areas, about 6–15 square meters (65–160 sq ft), were likely hut foundations. At a Magdalenian site in France, small circular dwellings were found. These sometimes had indoor hearths or sleeping areas. A 23,000-year-old hut in Israel used grasses for flooring or bedding. A 13,800-year-old stone slab from Spain has engravings that might show dome-shaped huts.

Over 70 dwellings made of mammoth bones have been found. Most are on the Russian Plain. These were likely semi-permanent hunting camps. They seem to have built structures similar to tipis. These huts were usually built after the LGM, after 22,000 years ago. The earliest known mammoth hut is from Ukraine, dating to 44,000 years ago. It might have been built by Neanderthals. These huts were typically 5 meters (16 ft) in diameter, or 4x6 meters (13x20 ft) if oval. Some were as small as 3x2 meters (10x7 ft). The largest hut found was 12.5 meters (41 ft) in diameter. It was made of 64 mammoth skulls. But it might have been used for food storage, not living. Some huts have burned bones. This suggests bones were used as fuel because firewood was scarce.

Mammoth hut foundations were made by pushing many mammoth skulls into the ground. Walls were made by placing shoulder blades, pelvises, and long bones vertically. Long bones were often used as poles. The foundation could go 40 centimeters (16 in) underground. Usually, several huts were built close together. Tusks might have been used for entrances. Animal skins likely covered the roofs. The inside was sealed with dirt. Some architectural choices seemed to be for looks. For example, in Ukraine, some huts had jaws stacked to create zigzag patterns. This zigzag pattern was common on the Russian Plain. It was painted or engraved on bones, tools, and mammoth skulls.

Dogs

At some point, EEMH domesticated dogs. This probably happened because dogs helped them hunt. DNA evidence suggests modern dogs split from wolves around the start of the LGM. However, some possible early dogs have been found even earlier. These include the 36,000-year-old Goyet dog from Belgium. This might mean there were several attempts to domesticate European wolves. These early "dogs" varied in size. They had shorter snouts and skulls, and wider palates than wolves. But the idea of dogs being domesticated by Aurignacian times is still debated.

At a 27,000-24,000-year-old site in the Czech Republic, three "dogs" were found. Their skulls were pierced, possibly to remove the brain. One had a mammoth bone in its mouth. Scientists thought this was a burial ritual. A 14,500-year-old dog from Germany was buried with a man and a woman. It had signs of a disease and likely died young. It would have needed a lot of human care to survive. This suggests a strong emotional bond between humans and dogs, not just a practical one.

The exact use of these early dogs is unclear. But they might have helped with hunting. They could also have helped carry things or guard camps.

Art

When Upper Palaeolithic art was first found, people thought it was "art for art's sake." They thought ancient people were uncivilized. But then detailed paintings were found deep inside caves, like Cueva de Altamira in Spain. It became clear that this art was more than just a hobby.

Cave Art

EEMH are famous for painting or engraving designs in caves. These include geometric shapes, hand stencils, plants, animals, and human-animal hybrids. The same animal species are often shown in different caves. These include mammoths, bison, lions, and bears. Images could be drawn on top of each other. Landscapes were never shown, except for a possible volcanic eruption at Chauvet Cave in France, dating to 36,000 years ago.

Cave art is found in dark parts of caves. Artists used fires or stone lamps to see. They used black charcoal and red and yellow ochre crayons. These could also be ground into powder and mixed with water to make paint. Large flat rocks might have been used as palettes. Brushes could be made from reeds or twigs. They might have used a blowgun to spray paint. Hand stencils were made by holding a hand to the wall and spitting paint over it. Some stencils are missing fingers. It's not clear if the artist was missing a finger or just left it out. It was often thought that men made the larger prints and boys the smaller ones. But it's unlikely that women were completely excluded. The meaning of cave art is still debated.

One early idea was that cave art showed totemism. This is where a group identifies with an animal. But this was questioned because some animals were shown wounded. Also, many different species were shown.

In 1903, a new idea suggested that cave art was for sympathetic magic. By drawing an animal, the artist believed they could control it. This "hunting magic" idea became popular. It suggested that wounded animals were drawn to cast a spell on them. Incomplete animals were drawn to weaken them. Geometric designs were traps. Human-animal hybrids were shamans or gods. This model also suggested fertility magic for pregnant animals. But this idea was later questioned. Many animals were shown healthy, and the bones found in caves often didn't match the animals in the art.

After the 1960s, scientists started using more statistics to study cave art. They looked at the types and locations of animals. They found that horses and bovines were often grouped together in central spots. Some animals and symbols were seen as male or female.

Later, with the idea that EEMH practiced shamanism, the human-animal hybrids and symbols were seen as visions. These visions might have been seen by a shaman in a trance. Critics argue that comparing ancient cultures to modern shamanistic societies might not be accurate.

Portable Art

Venus figurines are common in EEMH sites. They are the earliest known human figures. Most are from the Gravettian period, dating from 29,000 to 23,000 years ago. Almost all Venuses are small enough to hold in your hand. They have a downturned head, no face, thin arms, and a large belly (thought to mean pregnancy). Their legs are tiny and bent.

Early ideas about Venuses thought they showed obese women. Another idea was that obesity was the ideal for EEMH women. But this was questioned. Another idea is that Venuses were mother goddesses. Or that drawing a pregnant woman would bring fertility. This is also debated, as it assumes women are only seen for having children.

EEMH also carved perforated batons from horn, bone, or stone. These were common during the Solutrean and Magdalenian periods. Their purpose is debated. They might have been for spiritual reasons, decoration, money, drumsticks, or tools for making spears.

EEMH also made animal figures. As of 2015, about 50 Aurignacian ivory figures have been found in Germany. Most are mammoths and lions. Some are horses, bison, and other animals. These sculptures were small and portable. Some were even made into pendants. Some figures had mysterious engravings and patterns.

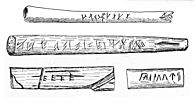

EEMH also made symbolic engravings. Some bone or antler plaques have evenly spaced notches. The 32,000-year-old Blanchard plaque from France has 24 marks in a wavy pattern. Scientists thought this might be an early counting system or a calendar. In 1972, some Magdalenian plaques with abstract symbols were found. They were thought to be an early writing system.

A complex engraving on a mammoth tusk from the Czech Republic was thought to be a map. It showed a river, a mountain, and a living area. Similar engravings have been found across Europe. They might be maps, plans, or stories.

Body Art

EEMH often used large pieces of pigments, called "crayons," made of red ochre. It's thought they used ochre for symbolic reasons, like body paint. This is because ochre was sometimes brought from very far away. It was also found in burials. It's not clear why they chose red ochre. Some ideas suggest it was for social signals or for its practical uses. Ochre could be used in adhesives, for tanning hides, as insect repellent, or even as medicine. EEMH ground and crushed ochre before putting it on their skin.

In 1962, archaeologists found needles in France. They thought these might have been used for tattooing.

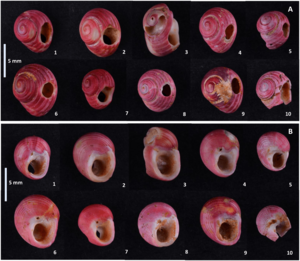

Clothing

EEMH made beads. These were likely attached to clothing or items for decoration. Bead making increased a lot in the Upper Palaeolithic. Communities often used local materials for beads for a long time. For example, Mediterranean groups used specific seashells for over 20,000 years. Central and Western European groups used pierced animal teeth. Aurignacian beads were made from shells, teeth, ivory, stone, bone, and antler. They also used fossil materials like amber. Beads came in many shapes. They might have been used to show a person's social status or wealth. Burials show that jewelry was mostly worn on the head.

At sites in the Czech Republic, many clay pieces with textile impressions were found. These show a very advanced textile industry. They made different types of string, cordage, and knotted nets. They also made woven cloth, including simple and patterned fabrics. Some items might have been baskets or mats. These people used plant fibers, not animal fibers. Plant fiber fragments have also been found in Russia and Germany.

In Georgia, people seemed to be dyeing flax fibers with plant-based dyes. They used colors like yellow, red, pink, blue, and black. The appearance of textiles in Europe happened at the same time as the spread of the sewing needle. Ivory needles are found in most late Upper Palaeolithic sites. Small needles might have been used for soft fabrics or embroidery.

There is some evidence of simple loom technology. But these objects have also been seen as hunting tools or art. Round objects from Russia might have been loom weights. Perforated ivory or bone discs might have been spindle whorls. A foot-shaped ivory piece from Germany might have been a comb. EEMH might have also used net spacers or weaving sticks.

Some Venus figurines show hairstyles and clothes worn by Gravettian women. The Venus of Willendorf seems to wear a cap, possibly woven or made of shells. The Venus of Brassempouy seems to wear a hair cover. The engraved Venus of Laussel might wear a snood. Many Eastern European Venuses with headwear also show patterns on their upper bodies, suggesting bandeaux. Some also wear belts. The Venus of Lespugue seems to wear a skirt made of plant fibers.

Music

EEMH made flutes from hollow bird bones and mammoth ivory. They first appeared around 40,000 years ago in Germany. These flutes could make many different sounds. One almost complete flute made from a vulture bone was 21.8 cm (8.6 in) long. It had holes that were carefully placed, possibly to create specific musical notes. Ivory flutes took a lot of time and skill to make. EEMH also made bone whistles from deer bones.

Such advanced musical tools suggest a longer history of music than we can see from archaeological finds. Modern hunter-gatherers make instruments from materials that don't last, like reeds and gourds. They also use natural items like horns or even their weapons.

Some EEMH artifacts might be bullroarers or percussion instruments like rasps. One possible bullroarer from France dates to 14,000-12,000 years ago. It is 16 cm (6.3 in) long and has geometric patterns. In mammoth-bone houses in Ukraine, large mammoth bones showed signs of paint and repeated hitting. These were thought to be drums. Other sites have found possible percussion mallets made of mammoth bone or reindeer antler. Some scientists think EEMH marked certain cave sections with red paint. When hit, these spots might have made sounds that echoed through the cave, like a xylophone.

Language

Early modern humans likely had the same vocal abilities as people today. The gene for speech, FOXP2, seems to have evolved within the last 100,000 years. The modern human hyoid bone, which helps with speech, evolved by 60,000 years ago. This means Upper Palaeolithic humans could make the same sounds as people today.

It's hard to know what early EEMH languages sounded like. Words change quickly over time. It's hard to find words that are related from before 9,000-5,000 years ago. Some scientists have suggested that all Eurasian languages are related. They form the "Nostratic languages" and share a common ancestor from after the LGM. In 2013, some scientists suggested that 23 common words were "ultraconserved." They supposedly changed very little over 15,000 years. But other scientists argue that this is based on subjective interpretation. Words change too quickly to track them that far back.

Religion

Shamanism

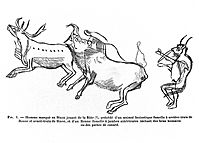

Many Upper Palaeolithic caves show drawings of human-animal creatures. These are often called "anthropozoomorphs" or "sorcerers." They are usually part human and part bison, reindeer, or deer. These figures are often seen as central to shamanism. They might represent a cultural change and the start of complex beliefs. The oldest such drawing is from 30,000-year-old Chauvet Cave. It shows a figure with a bison upper body and human lower body.

The 17,000-year-old Lascaux cave in France has a drawing of a bird-human hybrid. It is near a rhino and a charging bison. A bird on a pole is near the figure's hand. In some modern shamanistic cultures, birds are seen as guides between the living and the dead. Shamans might transform into birds or use them as spirit guides. The 14,000-year-old Grotte des Trois-Frères in France has three sorcerers. One, called "The Dancing Sorcerer," has human legs, paws, a deer head with antlers, and a fox or horse tail. Another smaller sorcerer with a bison head seems to be playing a musical bow to herd animals. The third has a bison upper body and human lower body.

Some human figures in drawings have lines radiating from them. These are often seen as wounded people, with the lines showing pain or spears. This might be part of an initiation for shamans. One "wounded man" is drawn on the chest of a red Irish elk. A wounded sorcerer with a bison head is found at the 17,000-year-old Grotte de Gabillou. Some caves show "vanquished men" lying dead near a bull or bear.

For portable art, the early Aurignacian site of Hohlenstein-Stadel in Germany yielded the famous lion-human sculpture. It is 30 cm (12 in) tall, much larger than other figures. Another possible lion-human was found nearby. An ivory slab from Geissenklösterle has a carving of a human figure with raised arms, called the "worshipper." A 28,000-year-old "puppet" was found in the Czech Republic. It had a separate head, torso, and arm. It was found in a grave. It's thought to have belonged to a shaman for rituals involving the dead. A 14,000-year-old stone from Spain seems to be carved with the conjoined faces of a man and a big cat.

Some Spanish archaeologists argued that a cave in Spain was a sanctuary for rituals. They said people dug a trench and filled it with offerings. These included shells, pigments, and animal parts. Then they buried it with dirt, clay, stones, and spearpoints. A large limestone slab covered it. Similar structures have been found in other Magdalenian sites in Spain.

Burial Practices

EEMH buried their dead. They often included symbolic items and red ochre in the graves. Sometimes, multiple people were buried together. However, few graves have been found, less than 5 per thousand years. This might mean burials were rare. It's unclear if these were special burials or a common tradition. Many graves contained multiple people, often both sexes.

Most burials are from the Gravettian period (31,000-29,000 years ago) and the end of the Magdalenian (14,000-11,000 years ago). No burials are found from the Aurignacian period. Gravettian burials are different from those after the LGM. Gravettian burials are found across Europe, from Portugal to Siberia. Post-LGM burials are mostly in Italy, Germany, and southwest France. About half of buried Gravettians were infants. Infant burials were less common after the LGM. Graves often had animal remains and tools. But it's unclear if these were intentional grave goods. Post-LGM graves had more ornaments than Gravettian ones.

The most elaborate Palaeolithic burial is from Sungir, Russia. A boy and a girl were buried head-to-head. They were covered with thousands of ivory beads, fox teeth, ivory pins, and mammoth tusk spears. The beads were smaller than those found with an adult man from the same site. This suggests they were made for children. This grave is unique for having functional tools (spears) and a bone from another person. The other five buried people at Sungir did not have as many grave goods.

Because of the rich items in some graves, it's thought these people had a complex society. They might have had social classes. Young people with elaborate funerals might have been born into high status. However, about 75% of EEMH skeletons found were men. This is different from the art, which mostly shows women. Making all these grave goods would have taken a lot of time and effort. It's thought they were made long before the burial. Elaborate funerals and evidence of shamanism suggest EEMH might have believed in an afterlife.

In Movies and Books

The "caveman" is a popular character in books and movies. They are often shown as muscular, hairy, and wild. They are usually seen in front of a cave or fighting dangerous animals. They use stone, bone, or wooden tools. Men often have long, messy hair and beards. Cavemen first appeared in movies in 1912. Early books about them include The Story of Ab (1897) and Before Adam (1907).

Cavemen are also often shown (incorrectly) fighting dinosaurs. This first happened in a 1914 movie. EEMH are also shown interacting with Neanderthals in many stories. These include The Quest for Fire (1911), The Grisly Folk (1927), and Clan of the Cave Bear (1980). EEMH are usually shown as being better than Neanderthals, which allowed them to take over Europe.

See also

In Spanish: Hombre de Cromañón para niños

In Spanish: Hombre de Cromañón para niños

- Early modern human

- Châtelperronian

- Lincombian-Ranisian-Jerzmanowician

- Federmesser culture

- Ahrensburg culture

- Swiderian culture

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |