El Camino Real (California) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids El Camino Real |

|

|---|---|

| The Royal Road | |

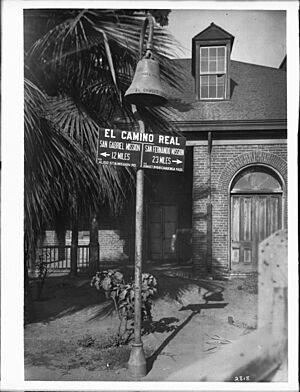

East entrance of San Gabriel Mission with an El Camino Real bell

|

|

| Location | |

| Counties: |

|

| Highway system | |

| State highways in California(list • pre-1964) History • Unconstructed • Deleted • Freeway • Scenic |

|

| Reference #: | 784 |

El Camino Real is a famous historic route in California. Its name means "The Royal Road" or "The King's Highway" in Spanish. This special route is about 600 miles (965 kilometers) long. It connects the 21 old Spanish missions in California. These missions were built a long time ago when California was part of the Spanish Empire.

The route also links several smaller missions, four forts called presidios, and three towns known as pueblos. The modern El Camino Real starts in the south at Mission San Diego de Alcalá. It ends in the north at Mission San Francisco Solano in Sonoma, California.

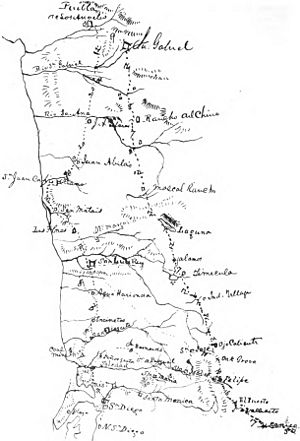

Historically, there wasn't just one single road built by the Spanish. Instead, a network of "royal roads" followed old Native American trading paths. These paths covered much of what is now California. The name "El Camino Real" became popular again in the early 1900s. This was during a time when people wanted to celebrate California's mission history. Today, many streets in California are named "El Camino Real." The route is marked with special bell markers.

Contents

Exploring the Spanish and Mexican Eras

In the past, during Spanish rule, any important road controlled by the Spanish crown was called a camino real. These roads connected major towns across Spain and its colonies. Many missions were built in what is now Baja California, Mexico, before any were built in present-day California. The first mission there was established in 1697.

The Portolá Expedition's Journey

In 1769, the Portolá expedition began its journey. It included Franciscan missionaries led by Junípero Serra. Serra started the first of the 21 California missions in San Diego. While Serra stayed in San Diego, Juan Crespí and Gaspar de Portolá continued north. They followed the coastline, exploring new areas.

The expedition eventually reached the entrance to San Francisco Bay, known as the Golden Gate. They could not go further north. On their way back to San Diego, Portolá found a shorter way around some cliffs. This route went through the Conejo Valley.

In 1770, Portolá traveled again from San Diego to Monterey. Junípero Serra, who traveled by ship, founded the second mission there. This mission was later moved to Carmel. Carmel then became Serra's main mission headquarters in Alta California.

The Juan Bautista de Anza Expedition

Another important journey was the Juan Bautista de Anza expedition in 1775–76. This group entered California from the southeast. They joined Portolá's trail at Mission San Gabriel. De Anza's scouts found easier paths through inland valleys. These were often better than the rugged coast.

On his trip north, de Anza traveled through the San Fernando Valley and Salinas Valley. He visited the Presidio of Monterey on the coast. Then, he went inland again, following the Santa Clara Valley. His journey continued to the southern end of San Francisco Bay and up the east side of the San Francisco Peninsula.

Myths and Legends of the Trail

Some people used to say that the missions were built about 30 miles (48 kilometers) apart. This was supposedly to make travel by horseback easier. However, this idea is not found in old historical records. It first appeared in advertisements in the 1900s to encourage car travel. In reality, the missions are spaced at different distances.

There's also a traditional story that the padres (mission priests) sprinkled mustard seeds along the trail. The bright yellow flowers would then mark the path. This would create a "golden trail" from San Diego to Sonoma. This legend is a nice story, but it has not been proven true.

The American Era and Commemorative Bells

By the mid-1800s, when California became a state, parts of the route had been improved. But it was still not good enough for large stagecoaches or heavy wagons. In 1892, a woman named Anna Pitcher started an idea to create a special commemorative route. This idea was supported by the California Federation of Women's Clubs in 1902.

The Famous Bell Markers

In the early 1900s, people wanted to mark important roads. Since there were no standard road signs, they decided to place unique bells along the route. These bells hung on tall supports shaped like a shepherd's crook. This shape was also described as a "Franciscan walking stick." Mrs. A. S. C. Forbes designed the bells. Her company, the California Bell Company, made them.

The first of 450 bells were put up on August 15, 1906. They were placed at the Plaza Church near Olvera Street in Los Angeles. A 1915 map from the Automobile Club of Southern California helped motorists follow the mission route. This club and other groups took care of the bells for many years.

Restoring the Bells

Over time, many bells disappeared due to damage, theft, or changes in road routes. The State of California took over bell maintenance in 1933. After the number of bells dropped to about 80, the state began replacing them. Justin Kramer started making the bells in 1959.

In 1996, the California Department of Transportation (Caltrans) began a big effort to restore the bells. By 2005, 555 new bell markers were installed. These new bells were made using the original molds from 1906. Each bell is typically marked "1769 & 1906." These dates represent the founding of the first mission in San Diego and the placement of the first commemorative bell.

A Difficult History for Some

For some indigenous peoples (Native Americans), these bells are painful symbols. They represent a time when their ancestors faced hardship and their culture was suppressed. The Amah Mutsun tribal band, for example, explained that the bells remind them of historical injustices. They shared how their people were punished for missing a bell's ring.

Because of these concerns, a bell at the University of California, Santa Cruz was removed in June 2019. Similar discussions happened when statues of Junípero Serra were damaged or removed in 2020. These actions were part of wider protests about monuments linked to the treatment of indigenous peoples. In November 2020, the historical commission of Santa Cruz reported that the bells represent a difficult history for the city's indigenous people. The last bell in Santa Cruz was scheduled for removal in August 2021. However, it was stolen the night before it could be taken down. Local tribal groups still held a ceremony to mark the occasion.

Modern Roads Following the Historic Route

Today, parts of El Camino Real follow modern highways. Other large sections are on city streets. For example, much of the route between San Jose and San Francisco uses city roads.

Main Route Sections

The California State Legislature has defined the full commemorative route. Here are some of the main sections:

| Destinations | Notes |

|---|---|

| Interstate 5 | From the U.S.-Mexico border to Anaheim |

| Anaheim Boulevard, Harbor Boulevard, State Route 72 and Whittier Boulevard | From Anaheim to Whittier |

| Various local roads like Valley Boulevard and Mission Road | From Whittier to Los Angeles |

| U.S. Route 101 | From Los Angeles to San Jose |

| State Route 87 | Within San Jose |

| State Route 82 | From San Jose to San Francisco |

| Interstate 280 | Within San Francisco |

| U.S. Route 101 | From San Francisco to Novato |

| State Route 37 | From Novato to Sears Point |

| State Route 121 | From Sears Point to Sonoma |

| State Route 12 | Within Sonoma |

East Bay Route Sections

There is also an "East Bay" route that connects different areas:

| Destinations | Notes |

|---|---|

| State Route 87 | Within San Jose |

| State Route 92 | From San Jose to Fremont |

| State Route 238 | From Fremont to Hayward |

| State Route 185 | From Hayward to Oakland |

| State Route 123 | From Oakland to San Pablo (and on to Martinez) |

Some older local roads that run next to these main routes also share the name. For example, Mission Street in San Francisco follows the commemorative route. An unpaved part of the old road is preserved near Mission San Juan Bautista. This section runs next to the San Andreas Fault, where you can clearly see the ground drop.

A section of the old mission road, El Camino Real, is in front of the Rios-Caledonia Adobe in San Miguel. This road was used by stagecoaches and later paved as part of the original US 101 highway.

The route through San Mateo and Santa Clara counties is called State Route 82. Parts of it are named El Camino Real. This old road is part of the de Anza route. It is located a few miles west of Route 101.

Historic Landmarks and Markers

El Camino Real is recognized as California Historical Landmark #784. There are two state historical markers that honor this important road. One is located near Mission San Diego de Alcalá in San Diego. The other is near Mission San Francisco de Asís in San Francisco.

See also

In Spanish: Camino Real de California para niños

In Spanish: Camino Real de California para niños

- El Camino Real de los Tejas

- El Camino Viejo, another old trail in colonial California

- History of California

| Bayard Rustin |

| Jeannette Carter |

| Jeremiah A. Brown |