Emigrant Trail in Wyoming facts for kids

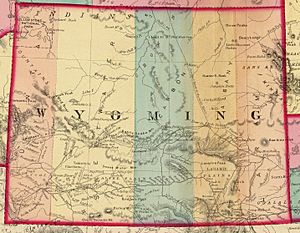

The Oregon Trail, California Trail, and Mormon Trail are famous paths that pioneers followed across the American West. Together, they are often called the Emigrant Trail. This trail stretches for about 640 kilometers (400 miles) through the state of Wyoming. It enters Wyoming from Nebraska near the town of Torrington and leaves near Cokeville and Afton on the western side. Between 1841 and 1868, an amazing 350,000 to 400,000 settlers traveled through Wyoming on these trails! Most of the time, all three trails followed the same path. However, the Mormon Trail split off at Fort Bridger to go into Utah, while the Oregon and California Trails continued into Idaho.

Contents

Following the North Platte River

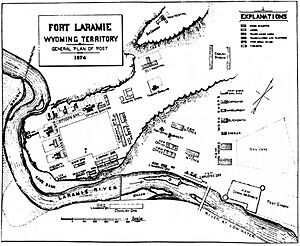

As pioneers traveled east, the Emigrant Trail followed the North Platte River into Wyoming. The trail went upstream along the river to Fort Laramie. This was a very important military and trading post. Before 1850, people thought the north side of the river was too hard to travel on past Fort Laramie. So, wagon trains on the north side had to make a risky crossing at the fort. Then, those on the main trail south of the river had to cross the North Platte again about 160 kilometers (100 miles) upstream!

New Routes Along the North Platte

In 1850, some wagon trains bravely found a new path along the northern side of the river. This new route was much better because it meant settlers didn't have to cross the river twice. It saved them risk and money. This northern path is sometimes called Child's Route, named after Andrew Child, who wrote about it in a guidebook in 1852. Beyond Fort Laramie, Child's Route followed the North Platte River through what is now Douglas. It also passed near where Fort Fetterman was built in 1867. This spot was also where the Bozeman Trail turned north in the 1860s, heading for the gold fields in Montana.

The southern route also followed the river. It went along the edge of the Laramie Mountains near the towns of Casper and Glenrock. In 1847, during the first Mormon journey, Brigham Young set up a ferry near present-day Casper. This was known as Mormon Ferry. The next year, the ferry moved a bit downriver. It was free for Latter-day Saints but charged a fee for others. Mormon groups operated this ferry every summer from 1848 to 1852.

Bridges and Landmarks

In 1853, John Baptiste Richard built a toll bridge near the ferry site. This bridge eventually made all the ferries on the North Platte go out of business. Later, in 1859, Louis Guinard built the Platte Bridge near the original Mormon Ferry spot. Guinard also built a trading post there, which later became Fort Caspar.

Along the southern route, pioneers saw famous landmarks like Ayres Natural Bridge. Another important spot was Register Cliff. This was one of many places in Wyoming where settlers carved their names into the rocks.

Journeying Along the Sweetwater River

After Casper, the North Platte River bends south. The original trail followed the river for several miles to Red Buttes. Here, the river curved, forming a natural area with red cliffs above. This was an easier place to cross the river for those who couldn't pay for the ferries downstream. It was also the last good camping spot before leaving the river. After this, pioneers faced a dry stretch of land before reaching the Sweetwater River.

Rock Avenue and Emigrant Gap

From Red Buttes, settlers entered a tough area called Rock Avenue. This path went from one spring to another across mostly salty soil and steep hills until it reached the Sweetwater River. Later, settlers who had crossed to the northern side of the river at Casper found a better way. They preferred a route through a small valley called Emigrant Gap. This path went directly to Rock Avenue, avoiding Red Buttes completely.

Independence Rock and Other Landmarks

When pioneers reached the Sweetwater valley, they saw one of the most important landmarks: Independence Rock. It got its name because settlers tried to reach it by July 4th (America's Independence Day). Reaching it by then helped them make sure they would arrive in California or Oregon before winter snows. Many travelers carved or painted their names on the rock using axle grease. It's believed that over 50,000 names were left on Independence Rock!

Other famous landmarks along the Sweetwater valley included Split Rock and Devil's Gate. There was also Martin's Cove. In November 1856, the Martin Handcart Company got stuck here in heavy snow. A rescue team from Salt Lake City finally arrived to help them.

River Crossings and Rocky Ridge

The trail continued west along the Sweetwater River, crossing it nine times. Three of these crossings were within a 3.2-kilometer (2-mile) section through a narrow canyon in the Rattlesnake Hills. Before the sixth crossing, the trail went over a unique spot called Ice Slough. This was a layer of peat-like plants growing over a small stream. The stream froze in winter and stayed frozen until early summer because the plants acted like insulation. This ice was a welcome treat for settlers in July, when temperatures could be over 32°C (90°F).

The trail crossed the Sweetwater three more times. Then, it met a large hill called Rocky Ridge on the north side of the river. This bare and rocky section was almost 19 kilometers (12 miles) long and was a major challenge. The same snowstorm in November 1856 that trapped the Martin Handcart Company also stranded the Willie Handcart Company on the east side of this ridge. Before rescuers could arrive, 21 people died in the freezing cold. After Rocky Ridge, the trail went down into the Sweetwater valley one last time for the ninth and final crossing at Burnt Ranch.

Seminoe Cutoff

In 1853, a new route called the Seminoe Cutoff was created on the south side of the river. It was named after a trapper, Basil LaJeunesse, whom the Shoshone Indians called Seminoe. The Seminoe Cutoff left the main trail at the sixth crossing and rejoined it at Burnt Ranch. This route avoided both Rocky Ridge and four of the river crossings, which was a big help in early spring and summer when the river was high. This route was used a lot in the 1850s, especially by Mormon groups.

Right after crossing the Sweetwater at Burnt Ranch, the trail crossed the continental divide at South Pass. This was definitely the most important landmark on the entire trail. South Pass itself is a simple, open area between the Wind River Range to the north and the Antelope Hills to the south. But it was a huge milestone for the travelers. In 1848, Congress created the Oregon Territory, which included all of Wyoming west of the Continental Divide. Crossing South Pass meant settlers had truly arrived in the Oregon Territory, even though their final destination was still far away. Nearby Pacific Springs offered the first water since leaving the Sweetwater River. It also marked the start of a fairly dry part of the trail until settlers reached the Green River, more than 64 kilometers (40 miles) away.

The Sandy River Area

Leaving Pacific Springs, the trail went southwest along Pacific Creek for a short distance. Then, it curved west to meet Dry Sandy Creek. This small stream flows into the Little Sandy River, which then flows into the Big Sandy River. As its name suggests, the water level in Dry Sandy varied and was often dry.

South of the Dry Sandy crossing, the trail split into two main parts. The main route continued south to Fort Bridger, and the Sublette Cutoff went west directly to the Green River and Bear River valleys, avoiding Fort Bridger. The place where the trails split is called Parting of the Ways. About 18 kilometers (11 miles) south, the main trail crossed the Little Sandy. Here, a second path to the Sublette Cutoff started from the Little Sandy Pony Express station. The main trail then went on to cross the Big Sandy near the town of Farson. The trail followed the north side of the Big Sandy to where it met the Green River. Crossing the Green River was very risky, so most travelers used one of the many ferries there, like the Lombard Ferry and the Robinson Ferry.

Fort Bridger: A Welcome Stop

Continuing towards Fort Bridger from the Green River, the main trail crossed Hams Fork near Granger and followed Blacks Fork to Fort Bridger. This fort was built in 1842 by the famous frontiersman Jim Bridger and his partner Louis Vasquez. Fort Bridger was a very important place to get supplies and a welcome rest after the tough journey from South Pass. Even after the Sublette Cutoff was created, settlers heading for Oregon who were low on animals and supplies would still go to Fort Bridger to restock.

Fort Bridger is the point where the Mormon Trail permanently separated from the Oregon Trail and California Trail. The Mormon Trail continued southwest, crossing the Bear River and entering Utah south of the current town of Evanston. The other trails turned northwest, crossing the Bear River Divide and entering the Bear River valley on the western side of the state. The trail met the Sublette Cutoff near Cokeville. The rejoined trails then followed the Bear River upstream and into Idaho, heading for Fort Hall.

Sublette-Greenwood Cutoff: A Shorter Path

The Sublette-Greenwood Cutoff was opened in 1844 by the Stephens-Townsend-Murphy Party. It was led by mountain men Caleb Greenwood and Isaac Hitchcock. Hitchcock, an old trapper, suggested that the wagon trail go directly west from the Little Sandy. This meant crossing about 64 kilometers (40 miles) of desert to the Green River. From there, it crossed a ridge into the Bear River Valley, completely avoiding Fort Bridger and the Bear River Ridge crossing. This route saved about 137 kilometers (85 miles) and 7 days of travel!

However, the decision to cross nearly 72 kilometers (45 waterless miles) before reaching the Green River was a serious one. Settlers had to choose between saving time and keeping their animals healthy. One traveler in 1846 wrote about this tough journey. This route became very popular during the California Gold Rush of the 1850s. People wanted to get to the California gold fields quickly, so they were willing to take the risks. Joseph Ware named the route the Sublette Cutoff in his popular 1849 guidebook, after Solomon Sublette. Even though it was named after Sublette, most experts today call it the Sublette-Greenwood Cutoff because Caleb Greenwood was one of its original discoverers.

Crossing the Green River on the Cutoff

Just like on the main route, several ferries operated where the cutoff crossed the Green River near the town of La Barge. Early settlers crossed at Names Hill Ford, which was barely passable when the water was low. Later, the Names Hill Ferry offered a safer way to cross. The nearby Mormon Ferry was a mile upstream, and the Mountain Man Ferry operated during the Gold Rush years. West of the ford is Names Hill, a famous spot where pioneers carved their names and other messages. One notable carving says "James Bridger, 1844, Trapper." It's not clear if this carving is real, as Bridger was known to be unable to read or write. The hill also has Native American pictographs (rock paintings).

A second cutoff, called the Slate Creek or Kinney Cutoff, branched off the main trail near the Lombard Ferry on the Green River. It met the Sublette Cutoff on Slate Creek Ridge at Emigrant Springs. This route was a little longer than the Sublette, but it had the advantage of only 16 waterless kilometers (10 miles) instead of the 72 kilometers (45 miles) on the Sublette trail.

Lander Cutoff: A Federally Built Road

The Lander Road was located further north than the main trail to Fort Hall. It also bypassed Fort Bridger and was about 137 kilometers (85 miles) shorter to Fort Hall. This road was built in 1858 under the direction of Frederick W. Lander by federal contractors. It was one of the first roads in the West paid for by the government. Lander's Road was officially called the Fort Kearney, South Pass and Honey Lake Road. It was a government effort to make the Oregon and California trails better.

Route and Benefits

The "Lander Road" was the first part of this federally funded road through what would become Wyoming and Idaho. Expeditions led by Frederick W. Lander surveyed a new route starting at Burnt Ranch, after the last crossing of the Sweetwater River. It then turned west over South Pass. The Lander Road followed the Sweetwater River further north, going around the Wind River Range before turning west and crossing the continental divide north of South Pass.

The road crossed the Green River near the town of Big Piney, Wyoming. Then it went over Thompson Pass, which is 2,682 meters (8,800 feet) high, in the Wyoming Range near the start of the Grey's River. It then crossed another high pass over the Salt River Range before going down into Star Valley (Wyoming). The trail entered Star Valley about 10 kilometers (6 miles) south of the town of Smoot, Wyoming. From Smoot, the road continued north for about 32 kilometers (20 miles) down Star Valley, west of the Salt River. Then it turned almost due west at Stump Creek near Auburn, Wyoming and went into Idaho. It followed the Stump Creek valley about 16 kilometers (10 miles) northwest over the Caribou Mountains (Idaho).

The Lander Road had good grass, fishing, water, and wood. However, it was high, rough, and steep in many places. Later, after 1869, ranchers mostly used it to move their livestock. You can find maps of the Lander Road in Wyoming and Idaho on the NPS National Trail Map. For more information, visit Afton, Wyoming to see its Lander and Pioneer Museum.

By crossing the green Wyoming and Salt River Ranges instead of going around through the southern deserts, this route provided plenty of wood, grass, and water for travelers. It also cut almost 7 days off the total travel time for wagon trains going to Fort Hall. Even though conditions were better for animals, the mountains and unpredictable weather sometimes made travel difficult. This meant the road needed ongoing government funding for maintenance, which was not always easy to get just before, during, and after the American Civil War. Funds were approved in 1858, and 115 men (hired in Utah) finished the road in Wyoming and Idaho in 90 days. They cleared trees and moved about 47,400 cubic meters (62,000 cubic yards) of earth. The Lander's road or cutoff opened in 1859 and was used a lot that year. Records after 1859 are missing, and it's thought its use dropped sharply. This is because the Sublette Cutoff, the Central Overland Route, and other cutoffs were just as fast or faster and much less difficult. Today, parts of the Lander Cutoff road are roughly followed by county and Forest Service roads.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Ruta del emigrante en Wyoming para niños

In Spanish: Ruta del emigrante en Wyoming para niños