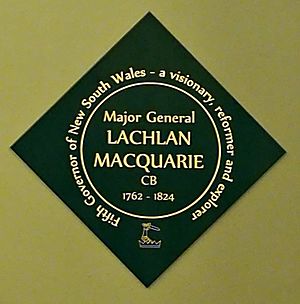

Lachlan Macquarie facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Lachlan Macquarie

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| 5th Governor of New South Wales | |

| In office 1 January 1810 – 30 November 1821 |

|

| Monarch | George III George IV |

| Preceded by | William Bligh |

| Succeeded by | Thomas Brisbane |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 31 January 1762 Ulva, Inner Hebrides, Scotland |

| Died | 1 July 1824 (aged 62) London, England |

| Spouses | Jane Jarvis (m. 1792–1796) Elizabeth Campbell (m. 1807) |

| Military service | |

| Branch/service | |

| Rank | |

| Commands | 73rd (Perthshire) Regiment of Foot |

| Battles/wars | American Revolutionary War Napoleonic Wars Australian Frontier Wars |

| Awards | Companion of the Order of the Bath |

Major General Lachlan Macquarie (born 31 January 1762 – died 1 July 1824) was a British Army officer from Scotland. He became the fifth Governor of New South Wales from 1810 to 1821. Macquarie played a huge role in shaping the early society of Australia. Many historians believe he helped change New South Wales from a penal colony (a place for prisoners) into a free settlement.

Contents

Early life and education

Lachlan Macquarie was born on a small island called Ulva in Scotland. His family was not rich, and his parents were likely unable to read or write. When he was a teenager, Macquarie went to Edinburgh for his education. There, he learned English and arithmetic, which helped him prepare for his future.

Joining the British Army

Service in America and India

Macquarie joined the British Army in 1776 when he was just 14 years old. He went to North America to fight in the American Revolutionary War. He later served in Jamaica.

In 1787, Macquarie joined the 77th (Hindoostan) Regiment of Foot, which was sent to India. He fought in several battles, including the Third Anglo-Mysore War. In 1793, he married Jane Jarvis, who sadly died a few years later. He continued to serve in India, fighting in the Fourth Anglo-Mysore War and helping the British take control of new areas.

Adventures in Egypt and return to Britain

In 1801, Macquarie was part of a large British-Indian army sent to Egypt. Their goal was to remove the French Army from the area. He stayed in Egypt for about a year.

By 1803, Macquarie returned to Britain. He had saved a good amount of money and bought an estate on his home island of Mull. In 1807, he married his third cousin, Elizabeth Henrietta Campbell. He then took command of the 73rd Regiment in Scotland.

Governor of New South Wales

Arriving in Sydney

On 8 May 1809, Lachlan Macquarie was chosen to be the new Governor of New South Wales. He arrived in Sydney on 28 December 1809, bringing his own army unit, the 73rd Regiment. This was important because the previous governor, William Bligh, had been overthrown by a group of officers called the New South Wales Corps. Macquarie's arrival with his own troops helped him take control without a fight.

His first job was to bring back order and law to the colony after the "Rum Rebellion." He cancelled many decisions made by the rebel government.

Making Sydney a modern city

Macquarie wanted to change the convict settlement into a proper urban area with organized towns, streets, and parks. He designed the street layout for central Sydney that we still see today. He named Macquarie Street after himself, and many important buildings were built there. These included parts of what is now the Parliament House of New South Wales.

Other famous buildings from his time include the Parramatta Female Orphan School, St James Church, and the Hyde Park Barracks. He also officially named Hyde Park as a public recreation area. Macquarie built these structures even though the British government did not want him to spend so much money on public projects.

He also toured other areas, naming and planning towns like Liverpool, Windsor, and Richmond. In Hobart, Tasmania, he ordered a new, organized street layout because the town was very messy. Macquarie also made traffic in New South Wales keep to the left side of the road.

Macquarie created Australia's first official currency. In 1812, he bought 40,000 Spanish dollar coins. He had a skilled forger cut the centers out of them and stamp them. The center piece, called a "dump," was worth 15 pence. The outer ring, called a "holey dollar," was worth five shillings. He also helped start the colony's first bank, the Bank of New South Wales, in 1817.

Social changes and helping former convicts

Macquarie wanted to improve the behavior and order in the colony. He encouraged marriage and church attendance. A key part of his plan was to help "emancipists." These were convicts whose sentences had ended or who had been pardoned. Macquarie wanted them to live good, law-abiding lives.

He believed that skilled or wealthy former convicts could be good role models. He gave them higher social standing and important government jobs. For example, Francis Greenway became the colonial architect, and Dr. William Redfern became the colonial surgeon.

Some wealthy colonists, called "exclusives," were very upset by these appointments. They refused to work with the promoted ex-convicts. However, an inquiry in 1812 supported Macquarie's policies. It said that the colony should be prosperous to provide work for convicts and encourage them to become settlers after their freedom. Macquarie also gave land grants to emancipists, helping them become farmers.

Judicial system improvements

Macquarie also tried to improve the justice system. Since there were not many lawyers, he allowed former lawyers who had been convicts, like Edward Eagar, to work on civil cases. This caused problems with the first judge of the Supreme Court of New South Wales, Jeffery Hart Bent, who refused to hear cases from ex-convict lawyers. This disagreement led to the British government recalling Bent and criticizing Macquarie.

Encouraging exploration

Macquarie strongly supported British exploration in the colony. He went on many expeditions himself around Sydney and to other areas like Jervis Bay and the Hunter River. He often named new places after himself, his wife, or important British people.

In 1813, he allowed Gregory Blaxland, William Wentworth, and William Lawson to cross the Blue Mountains. They were the first non-Indigenous people to see the vast plains beyond. Later, George Evans explored this area further and named the Macquarie River. In 1815, Macquarie ordered the creation of Bathurst on this river, which was Australia's first inland British settlement.

He also appointed John Oxley as surveyor-general. Oxley explored the Lachlan River and the north coast of New South Wales, naming Port Macquarie after the Governor.

Dealing with Aboriginal Australians

Macquarie's approach to Aboriginal Australians involved both trying to cooperate and using military force. When he arrived in 1810, he said he wanted "Natives of this Country...to be always treated with kindness." For the first four years, there was little conflict. However, in 1814, some settlers and Aboriginal people were killed in clashes near the Nepean River. Macquarie tried to promote peace but also sent armed groups to patrol the area.

To improve relations, Macquarie held a conference for Aboriginal people in 1814. In 1815, he opened the Parramatta Native Institution to educate Aboriginal children in the British way. Some children were taken from their parents for this school. While the children seemed well-treated, the institution aimed to reduce Indigenous culture.

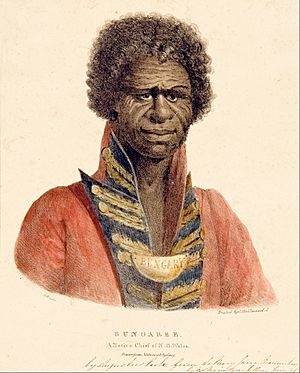

Macquarie also rewarded Aboriginal people who helped the British. He declared them "chiefs of their tribe" and gave them special brass breast-plates, called gorgets, with their names and titles. He also gave them small pieces of land for their families. Bungaree was one of the first to receive these rewards in 1815.

However, conflicts continued. In March 1816, a large group of Aboriginal people killed four settlers at Silverdale.

On 17 April, a British army group led by Captain James Wallis attacked a large group of Gandangara and Tharawal people near the Cataract River. At least 14 men, women, and children were killed in what became known as the Appin Massacre. Macquarie rewarded Wallis for his actions. Hostilities continued into 1817, which led to the end of Aboriginal resistance in the Hawkesbury and Nepean Wars.

Bigge's investigation and Macquarie's resignation

Macquarie's policies, especially helping former convicts and spending a lot of money on public buildings, caused opposition in the colony and in London. The British government still saw New South Wales mainly as a prison colony. So, in 1819, an English judge named John Bigge was sent to investigate Macquarie's administration.

Bigge spoke with wealthy colonists who disagreed with Macquarie's social reforms. They wanted convicts to work on their large sheep farms instead of on government building projects. Bigge agreed, saying that Macquarie's policies were not good for the colony.

Macquarie offered to resign several times, and his resignation was finally accepted in 1820. Thomas Brisbane replaced him as governor in 1821. Macquarie served longer than any other governor.

Return to Scotland, death, and legacy

Macquarie returned to Scotland and died in London in 1824. After his death, his reputation grew, especially among the former convicts and their families. Many people now see him as one of the most forward-thinking early governors who helped establish Australia as a country, not just a prison.

Macquarie officially adopted the name "Australia" for the continent in 1817. Many places and institutions in Australia are named after him, including Macquarie University in Sydney. He was promoted to Major-General in 1813 while he was governor.

Macquarie was buried on the Isle of Mull in Scotland with his wife and daughter. His grave is cared for by the National Trust of Australia and is inscribed "The Father of Australia."

Memorials

A statue of Lachlan Macquarie stands at the north entrance to Hyde Park in Sydney. It was created in 2012. An inscription nearby describes him as "a perfect gentleman, a Christian and supreme legislator of the human heart." However, some people question this description because of his actions against Indigenous people.

Places named after Macquarie

Many places in Australia are named in Lachlan Macquarie's honor. Some were named by him, and others later.

Places named during or shortly after his time as governor:

- Macquarie Island, located between Tasmania and Antarctica.

- Lake Macquarie, a large coastal lake in New South Wales.

- Macquarie River, an important inland river in New South Wales.

- Mount Macquarie, a high point in the Blayney Shire.

- Lachlan River, another significant river in New South Wales.

- Port Macquarie, a city on the coast of New South Wales.

- Macquarie Pass, a route connecting the Illawarra district to the Southern Highlands.

- Macquarie Rivulet, a river that flows into Lake Illawarra.

- Around Sydney:

- Macquarie Street, a main street in Sydney's city center.

- Macquarie Place, a small park in Sydney.

- Macquarie Lighthouse, Australia's first lighthouse.

- Macquarie Fields, a suburb of Sydney.

- In Tasmania:

- Macquarie Street, a main street in Hobart.

- Macquarie Harbour, on the west coast.

- Macquarie River, a major river in the Midlands region.

- In New South Wales:

- Macquarie Pier, a breakwater at the mouth of the Hunter River in Newcastle.

- The Macquarie Arms Hotel in Windsor, New South Wales, built in 1815.

Places named many years after his governorship:

- Macquarie Park and Macquarie Links, suburbs of Sydney.

- Macquarie Shopping Centre, in North Ryde.

- Macquarie, a suburb of Canberra.

- Division of Macquarie, an area for the Australian Parliament created in 1901.

Institutions named after Macquarie:

- Macquarie Hospital, Sydney.

- Macquarie University, Sydney.

- Macquarie Group, an investment bank.

- Macquarie Community College, an adult education provider.

- Macquarie Grammar School, Sydney.

- Macquarie Correctional Centre, a prison in Wellington, New South Wales.

See also

In Spanish: Lachlan Macquarie para niños

In Spanish: Lachlan Macquarie para niños

- Historical Records of Australia

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |