History of African Americans in Philadelphia facts for kids

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 1,256,908 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| North Philadelphia west of Germantown Avenue, Point Breeze in South Philadelphia, West Philadelphia and parts of Southwest Philadelphia | |

| Languages | |

| Philadelphia English, African-American Vernacular English | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity, Islam, Irreligion |

This article tells the story of African Americans in Philadelphia. In 2010, over 644,000 people in Philadelphia identified as Black or African American. This made them the largest ethnic group in the city.

African Americans first arrived in Philadelphia in the 1600s, often as enslaved people. Over time, many became free. They played a big part in the movement to end slavery, known as abolitionism. They also helped people escape slavery through the Underground Railroad. In the 1900s and 2000s, Black Philadelphians kept fighting for equal rights. They have greatly contributed to the city's culture, economy, and politics as workers, artists, musicians, and leaders.

Contents

- A Look at History: African Americans in Philadelphia

- Important Places and Institutions

- Where People Live: Geography of Black Philadelphia

- Faith and Religion

- Learning and Education

- Famous People from Philadelphia's Black Community

A Look at History: African Americans in Philadelphia

Early Days: 1639 to 1800

African people were first brought to the Philadelphia area as enslaved people around 1639 by European settlers. By the 1750s, more enslaved Africans arrived each year. In 1765, about 1,500 Black people lived in Philadelphia. Only about 100 of them were free.

By the time the American Revolution started in 1775, enslaved people made up one-twelfth of Philadelphia's population. This was about 1,300 people out of 16,000.

Black People and the American Revolution

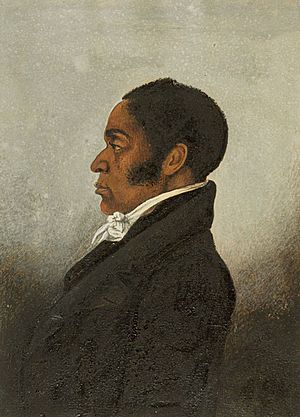

Black people fought on both sides during the American Revolution. Cyrus Bustill worked as a baker on ships for the American side. He later became a well-known businessman and activist in Philadelphia. James Forten joined a privateer ship at age 14. He later became a rich sailmaker and a strong voice against slavery.

Some enslaved people gained their freedom during this time. Others escaped or bought their freedom. By 1783, after the Revolution, over 1,000 free Black people lived in Philadelphia. About 400 people were still enslaved.

Steps Towards Freedom and Community Building

In 1780, Pennsylvania started a plan for gradual emancipation. This meant slavery would slowly end. Most Black people in Philadelphia were free by 1811. Some remained enslaved until the 1840s. Many free Black people came to Philadelphia. They included those who escaped from the South and people seeking safety from the Haitian Revolution.

Richard Allen and Absalom Jones started the Free African Society in 1787. This group helped its members in times of need. In 1794, Richard Allen and his wife, Sarah Allen, founded the Bethel African Methodist Church.

During the Yellow Fever Epidemic of 1793, people wrongly thought Black residents were safe from the disease. So, Black people bravely cared for the sick and dying. Even with freedom, there was a risk. Free Black people, especially children, could be kidnapped and sold back into slavery. This danger continued into the 1800s.

Abolitionism and Challenges: 1800 to the Civil War

Philadelphia became a major center for the movement to end slavery by the 1830s. This was thanks to the growing free Black community.

Wealthy Black businessman James Forten gave money to William Lloyd Garrison. This helped Garrison start The Liberator, an important anti-slavery newspaper. Black activists also helped create the American Anti-Slavery Society in Philadelphia in 1833. They also formed the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society in 1838.

In 1833, women were not allowed in the American Anti-Slavery Society. So, Black and white women started the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society (PFASS). This group included Grace Douglass, daughter of Cyrus Bustill, and James Forten's daughters, Sarah, Harriet, and Margaretta Forten.

Work, Conflict, and Growth

Some African Americans in Philadelphia had professional jobs. They worked as teachers, doctors, ministers, barbers, and caterers. But most Black Philadelphians had hard, low-paying jobs. They often competed with white workers, especially new Irish immigrants. This sometimes led to conflict.

In 1834, fights broke out between Black and white residents. A white mob attacked Black homes, businesses, and churches. In 1838, another white mob burned down Pennsylvania Hall. This was where Black and white abolitionists were meeting. Also in 1838, a new Pennsylvania law took away the right to vote from African Americans. In 1842, white mobs attacked Black people again during the Lombard Street Riots.

Despite these dangers, African Americans kept coming to Philadelphia. It was the closest big city to the Southern states where slavery was still legal. By 1830, Philadelphia had 15,000 Black residents. This grew to 20,000 by 1850 and 22,000 by 1860. Most lived in South Philadelphia, near what is now Center City. They came because Philadelphia was known as a place where African Americans could thrive.

The Underground Railroad in Philadelphia

Philadelphia was a key stop on the Underground Railroad. This secret network helped enslaved people escape to freedom. Robert Purvis was a leader of the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society. He also led the Vigilance Committee, which directly helped people escaping slavery.

With his wife Harriet Forten Purvis, Robert Purvis helped many people escape. They used their home as a hiding place. Purvis estimated they helped over 9,000 enslaved people find freedom between 1831 and 1861.

From Civil War to 1900: Progress and Challenges

During the American Civil War, eleven African American regiments from Philadelphia fought for the North. This was possible after a law in 1862 allowed Black people to join the Army.

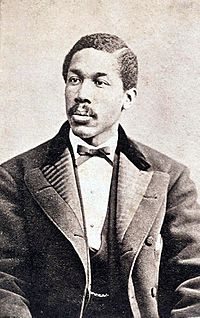

After the Civil War, Black Philadelphians worked to end segregation in schools and streetcars. They also fought to get back their right to vote. Octavius Catto was a key leader in these efforts. Their hard work paid off. In 1867, streetcar segregation ended. In 1881, legal segregation in schools ended, though it continued in practice.

The Fifteenth Amendment gave Black Americans the right to vote in 1870. Sadly, Octavius Catto was shot and killed in 1871 while trying to vote.

Arts, Business, and Community Growth

In 1879, Henry Ossawa Tanner became the first African American student at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. He later painted his famous work, The Banjo Lesson, in Philadelphia in 1893. Also in 1893, high school student Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller created art that was shown at a big exhibition. This led to her success as an artist.

The Black population grew to nearly 32,000 by 1880. By 1884, there were about 300 Black-owned businesses. These included the Philadelphia Tribune newspaper and Douglas Hospital. By 1900, the Black population had almost doubled to 63,000 people.

In 1896, Philadelphia poet and activist Frances Ellen Watkins Harper helped start the National Association of Colored Women's Clubs. She was its vice president. She had a long career as a writer, publishing poems and novels like Iola Leroy.

Understanding "The Philadelphia Negro"

In 1899, W. E. B. Du Bois published The Philadelphia Negro: A Social Study. This was the first major study of an African American community in the United States. It looked at the challenges faced by Black communities. The study focused on Philadelphia's Seventh Ward. Du Bois used facts and figures to show the differences in jobs, income, and education between Black and white residents. He used this information to challenge unfair ideas about the Black community.

The Great Migration and Beyond: 1900 to 1950s

World War I brought many Black people from the rural South to Philadelphia. This was part of the Great Migration. They came for wartime jobs. As a result, Philadelphia's Black population doubled again, from 63,000 in 1900 to 134,000 in 1920. Most new residents were working-class people from the countryside.

Housing Challenges and Community Action

There wasn't enough housing for all the new workers. African Americans moved into existing houses in white neighborhoods. This often led to anger and racism. In July 1918, white neighbors attacked two Black families. The editor of The Philadelphia Tribune newspaper wrote about the "Pine Street war Zone." He told Black residents to "stand your ground like men."

Soon after, racial violence broke out again. Black homes were destroyed, and three people died. In response, African Americans formed the Colored Protective Association. Led by Reverend RR Wright Jr., this group fought against discrimination in schools, housing, and jobs. They also looked into cases of police unfairness. Their efforts eventually led to changes in the police force.

Arts, Business, and the Great Depression

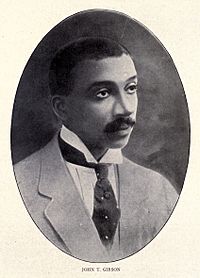

In 1925, artist Dox Thrash moved to Philadelphia. He spent most of his career there. Black Opals, a Black literary magazine, was published in Philadelphia from 1927 to 1928. It featured writers like Jessie Redmon Fauset. In the 1920s, John T. Gibson became a very rich Black businessman. He owned popular theaters and managed many musical and vaudeville shows.

The Great Depression was a very hard time for Black Philadelphians. By 1933, half of all Black residents were unemployed. Still, by 1935, African Americans owned many homes and stores. More Black people were also working in professional jobs like doctors, ministers, teachers, and police officers. Their neighborhoods became more concentrated and separate from white neighborhoods.

In 1938, Crystal Bird Fauset made history. She became the first African American woman elected as a state lawmaker.

World War II and Civil Rights Efforts

World War II brought jobs, but African Americans still faced poor housing. They were also not allowed to work as motormen or conductors on Philadelphia's public transit. The government had to step in to make the transit company open these jobs in 1944. White transit workers responded with a huge strike. The NAACP pushed for action. The government sent 5,000 troops to end the strike and keep public transportation running.

Philadelphia was also a center for Gospel music in the mid-1900s. Famous groups like the Dixie Hummingbirds and the Sensational Nightingales performed there.

Modern Times: 1950s to Present

The fight against unfair treatment in education and jobs continued through the 1950s and 1960s. There were legal battles and protests. Cecil B. Moore, a local NAACP leader, was a key activist. Leon Sullivan helped build Black community and economic power. Marie Hicks led protests and a lawsuit to desegregate Girard College. In 1964, a disagreement between police and residents led to a three-day riot.

The Black Power Movement

The 1960s saw the rise of the Black Power movement in Philadelphia. The Freedom Library in North Philadelphia became a meeting place for activists. They formed the Black Power Unity Movement in 1965. The Church of the Advocate was another important center. Father Paul Washington organized the first Black Power rally in 1966. Soon, rallies were held across the city.

Reggie Schell became the leader of the Philadelphia chapter of the Black Panther Party in 1969. Under his leadership, the party held rallies and created food and education programs. Black Power ideas spread to colleges and high schools. Students protested for more Black teachers and Black studies classes. In 1970, police raids on Black Power offices caused outrage. Later that year, a large convention sponsored by the Panthers attracted 14,000 people.

Music and Community Challenges

Philadelphia soul music became popular in the late 1960s and 1970s. This music had rich instrument sounds with strings and horns. It blended funk music with the disco sound that became popular later. It influenced Philadelphia-born artists like singer Jill Scott.

The group MOVE was founded in 1972. They lived together in West Philadelphia. In 1978, a conflict between MOVE and Philadelphia police resulted in the death of a police officer. Nine MOVE members were convicted. In 1985, another conflict occurred. A police helicopter dropped a bomb onto the roof of the MOVE compound. The fire that followed killed six MOVE members and five of their children. It also destroyed 65 houses in the neighborhood. The police action was widely criticized. MOVE survivors and other residents later won lawsuits against the city.

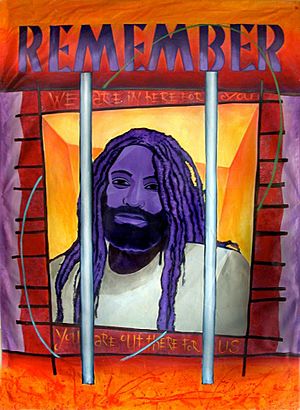

In 1982, Mumia Abu-Jamal, a Philadelphia activist and journalist, was convicted in connection with the death of a police officer. While in prison, he became well-known for his writings about the justice system. After many appeals, his death sentence was changed to life in prison in 2011.

Black Leaders in Politics

Many Black activists from the mid to late 1900s went on to hold political power. In 1975, Cecil B. Moore won a seat on the City Council. C. Delores Tucker became the first Black Pennsylvanian to be appointed Secretary of State. David P. Richardson was elected to the Pennsylvania House of Representatives in 1972.

In 1984, W. Wilson Goode became Philadelphia’s first Black mayor. After him, John F. Street and Michael Nutter also served as Black mayors of Philadelphia.

Even with ongoing challenges like unemployment, the Black community in Philadelphia continues to grow and contribute to the city. In 2010, Black residents made up 43.4 percent of Philadelphia's total population.

Important Places and Institutions

Philadelphia has many places that celebrate and support its African American community.

- The African American Museum in Philadelphia is in Center City.

- The Aces Museum honors Black World War II veterans.

- The Colored Girls Museum focuses on the history of Black women and girls.

- The National Marian Anderson Museum celebrates the life of famous opera singer Marian Anderson.

- The Paul Robeson House offers tours of the former home of this important artist and activist.

Where People Live: Geography of Black Philadelphia

Neighborhood Changes in the 20th Century

Around 1961, Society Hill was mostly a Black, low-income neighborhood. But by 1976, it became more expensive and mostly white. The remaining Black residents lived in a few high-rise buildings. Many Black families moved to Wynnefield as they became middle class. In 1976, many African Americans also lived in Powelton Village. These residents often came from other states and worked in professional jobs like artists, teachers, and writers.

Neighborhood Changes in the 21st Century

From 1990 to 2010, many Black residents moved away from North and West Philadelphia. They moved to Southwest Philadelphia, Overbrook, and other areas. For example, in the 19120 zip code (which includes Olney and Feltonville), the number of Black residents grew from about 9,700 in 1990 to over 33,000 in 2010. This was a huge increase.

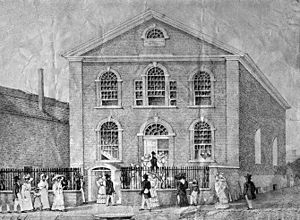

Faith and Religion

The African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas, started in 1792, was the first church created by and for Black people in the United States. Before this, Black worshipers at St. George's United Methodist Church were moved to a separate gallery area. This led them to leave and form their own church.

Learning and Education

The first school for Black boys was started by the Pennsylvania Abolition Society in 1794. In 1813, they built Clarkson Hall for the school. In 1854, they created the Lombard Street Infant School to help working parents.

In 1976, 66% of all students in the School District of Philadelphia were Black. Many white families chose private schools. Wealthier Black families often used public schools because their neighborhoods had good ones.

Famous People from Philadelphia's Black Community

From the 1700s and 1800s

- Richard Allen, religious leader and writer

- Sarah Allen, anti-slavery activist and Underground Railroad helper

- Cyrus Bustill, businessman and community leader

- Octavius Catto, educator and civil rights activist

- Rebecca Cole, doctor and social reformer

- James Forten, businessman and anti-slavery leader

- Grace Douglass, anti-slavery activist

- Sarah Mapps Douglass, educator

- Frances Harper, anti-slavery activist, women's rights supporter, poet, and author

- Absalom Jones, founder of the Free African Society

- Robert Purvis, anti-slavery leader who helped many escape slavery

From the 1900s and 2000s

- Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller, artist

- Henry Ossawa Tanner, painter

- Bessie Smith, blues singer

- Alain LeRoy Locke, philosopher and writer from the Harlem Renaissance

- Billie Holiday, singer

- Ethel Waters, singer and actress

- Marian Anderson, famous opera singer

- Crystal Bird Fauset, first African American female state lawmaker

- Kobe Bryant, basketball player

- Michael Nutter, Mayor of Philadelphia

- John F. Street, Mayor of Philadelphia

- Teddy Pendergrass, singer

- Ed Bradley, news reporter

- Wilt Chamberlain, basketball player

- Will Smith, rapper and actor

- Guion S. Bluford, astronaut and scientist

- Kevin Hart, actor and comedian

- Patti LaBelle, singer and actress

- Jill Scott, singer

- Sherman Hemsley, actor

- Solomon Burke, singer

- W. Wilson Goode, Mayor of Philadelphia

- Mumia Abu-Jamal, activist and journalist

- Bill Cosby, comedian and actor