History of Ivory Coast facts for kids

Humans first arrived in Ivory Coast (officially called Côte d'Ivoire) a very long time ago, possibly between 15,000 and 10,000 BC. We know this from old tools and weapon pieces found there, like polished stone axes. The earliest people in Côte d'Ivoire left clues all over the land. Historians think these early groups either moved away or joined with the ancestors of the people living there today. Some of these groups, who arrived before the 16th century, include the Ehotilé, Kotrowou, Zéhiri, Ega, and Diès.

Contents

Early History and Ancient Empires

We don't know much about the very first people of Côte d'Ivoire. The earliest written records come from North African Muslims. They traded across the Sahara Desert using camel caravans. They traded salt, gold, and other goods. The main trading spots were at the edge of the desert. From there, trade routes went further south into the rainforest areas.

Important trading cities like Djenné, Gao, and Timbuctu grew into big business centers. Powerful empires in the Sudanic region grew around these centers. They controlled the trade routes with strong armies. These empires also became places of learning for Islam. Arab traders from North Africa brought Islam to western Sudan. It spread quickly when many important rulers became Muslim. By the 11th century, Islam had reached the northern parts of what is now Ivory Coast.

The Ghana Empire was the first of these Sudanic empires. It was strong from the 4th to the 13th century in what is now eastern Mauritania. At its strongest, it stretched from the Atlantic Ocean to Timbuctu. After Ghana declined, the Mali Empire became a powerful Muslim state. It was strongest in the early 14th century. The Mali Empire's reach into Ivory Coast was only in the northwest, near Odienné.

The Songhai Empire was powerful from the 14th to the 16th centuries. But problems within the empire led to fighting. This fighting caused people to move south toward the thick forest areas. The dense rainforest in the south made it hard for large empires to form there. Instead, people lived in villages or small groups of villages. They traded with distant merchants and lived by farming and hunting.

Before Europeans Arrived

Five important kingdoms grew in Ivory Coast before Europeans came. The Bono kingdom of Gyaman started in the 17th century. It was founded by the Abron people, an Akan group. They had left the growing Ashanti Empire in Ghana. From their home south of Bondoukou, the Abron slowly took control over the Juula people. Bondoukou became a big center for trade and Islam. Its religious scholars attracted students from all over West Africa.

In the mid-1700s, other Akan groups also fled the Ashanti Empire. They set up a Baoulé kingdom at Sakasso in east-central Ivory Coast. They also formed two Agni kingdoms, Indénié and Sanwi. The Baoulé had a very organized government, like the Ashanti. But their kingdom eventually split into smaller areas. Even so, the Baoulé strongly fought against French control. The Agni rulers' families tried to keep their separate identity even after Ivory Coast became independent. In 1969, the Sanwi people of Krinjabo even tried to break away and form their own kingdom.

In the early 1700s, the Juula people started the Muslim Kong Empire in the north-central region. This area was home to the Sénoufo people, who had moved there to avoid becoming Muslim under the Mali Empire. The Kong Empire was rich from farming, trade, and crafts. But it slowly became weaker because of different ethnic groups and religious disagreements. The city of Kong was destroyed in 1895 by Samori Touré.

Trade with Europe and the Americas

In the 15th century, Africa became a destination for European explorers. They were looking for new trade routes to the Far East. The first Europeans to explore the West African coast were the Portuguese. Other European countries followed and started trading with coastal peoples. At first, they traded gold, ivory, and pepper. But when colonies were set up in the Americas in the 16th century, there was a huge demand for slaves. This led to people being kidnapped and enslaved from West Africa and sent to North and South America. Local rulers traded goods and slaves from the interior to meet agreements with the Europeans. By the late 1400s, European trade had a strong influence on West Africa.

Ivory Coast was also affected by these changes. However, it didn't have good natural harbors. This meant Europeans couldn't set up permanent trading posts easily. So, sea trade was not regular and didn't play a big role in how Europeans eventually took over Ivory Coast. The slave trade, in particular, didn't affect the people of Ivory Coast much. A profitable trade in ivory existed in the 17th century, which gave the area its name. But the number of elephants dropped, and the ivory trade ended by the early 18th century.

The first recorded French trip to West Africa was in 1483. The French set up their first West African settlement, Saint Louis, in what is now Senegal in the mid-1600s. Around this time, the Dutch gave a settlement at Ile de Gorée to the French. The French also set up a small outpost in 1687 at Assinie, near the Gold Coast (now Ghana). This was the first European outpost in that area. But the French didn't really establish themselves in Ivory Coast until the mid-1800s. By then, the French had settlements along the coasts of Senegal, Gambia, and Guinea-Bissau. The British also had permanent outposts in these areas and east of Ivory Coast.

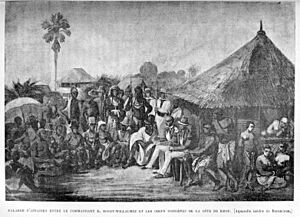

In the 18th century, two related Akan groups, the Agni and the Baoulés, moved into Ivory Coast. The Agni settled in the southeast, and the Baoulés in the central part. In 1843–1844, French Admiral Bouët-Willaumez signed agreements with the kings of the Grand Bassam and Assini regions. These agreements placed these areas under French protection. French explorers, missionaries, traders, and soldiers slowly expanded French control inland from the coastal lagoons.

Activity along the coast made Europeans more interested in the interior, especially along the Senegal and Niger rivers. French exploration of West Africa began in the mid-1800s. It was slow and often done by individuals, not just government policy. In the 1840s, the French made agreements with local West African rulers. This allowed the French to build forts along the Gulf of Guinea for trading. The first posts in Ivory Coast were at Assinie and Grand-Bassam. Grand-Bassam became the first capital of the colony. The agreements gave the French trading rights. In return, they paid annual fees to the local rulers for using their land. This arrangement wasn't perfect for the French because trade was limited. Also, there were often misunderstandings about the agreements. Still, the French government kept the agreements, hoping to expand trade. France also wanted to stay in the region to limit the growing influence of the British.

After France lost the Franco-Prussian War in 1871, the French government gave up its colonial plans for a while. They pulled their soldiers out of West African trading posts. They left the posts in the care of local merchants. The trading post at Grand-Bassam was left to Arthur Verdier, a merchant from Marseille. He was named a special minister when Ivory Coast was created in 1878.

In 1885, France and Germany brought European powers interested in Africa together at the Berlin Conference. This meeting helped organize what became known as the European "scramble for Africa." Prince Otto von Bismarck wanted Germany to have a bigger role in Africa. He thought he could do this by encouraging competition between France and Britain. The agreement signed in 1885 said that only European claims on the African coastline that involved actual occupation would be recognized. Another agreement in 1890 extended this rule to the interior of Africa. This led to a rush for territory by France, Britain, Portugal, and Belgium.

France Takes Control

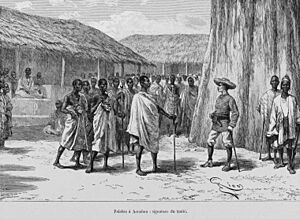

To support its claims of actually occupying the land, France took direct control of its West African coastal trading posts again in 1886. They started a faster program of exploring the interior. In 1887, Lieutenant Louis Gustave Binger began a two-year journey across Ivory Coast's interior. By the end of his trip, Binger had made four agreements that put parts of Ivory Coast under French protection. Also in 1887, Arthur Verdier's agent, Marcel Treich-Laplène, made five more agreements. These agreements spread French influence from the top of the Niger River Basin through Ivory Coast.

By the late 1880s, France had strong control over the coastal areas of Ivory Coast. Britain recognized French control in the area in 1889. France named Treich-Laplène the official governor of the territory in 1889. In 1893, Ivory Coast became a French colony. Agreements with Liberia in 1892 and with Britain in 1893 set the eastern and western borders of the colony. But the northern border wasn't set until 1947. This was when the French government wanted to add parts of French Upper Volta (now Burkina Faso) and French Sudan (now Mali) to Ivory Coast for economic and administrative reasons.

During this time, the African people often didn't pay much attention to the occasional European explorer. Many local rulers of small communities didn't understand, or were tricked by the French, about how important these treaties were. These treaties took away their power. However, some local leaders thought the French could help them with economic problems. Or they hoped the French would be allies if they had a fight with nearby groups. In the end, local rulers often lost their power because they couldn't fight against French tricks and military strength. It wasn't because they supported French takeover.

The French Colonial Period

Quick facts for kids

Colony of Côte d'Ivoire

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1893–1960 | |||||||||

|

Flag

|

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Capital | Grand-Bassam (1893–1896); Bingerville (1896–1934); Abidjan (1934–1960) | ||||||||

| Government | French colony | ||||||||

| President of France | |||||||||

|

• 1893–1894

|

Sadi Carnot | ||||||||

|

• 1959–1960

|

Charles de Gaulle | ||||||||

| Colonial governor | |||||||||

|

• 1893–1895

|

Louis-Gustave Binger (first) | ||||||||

|

• 1960

|

Yves Guéna (last) | ||||||||

| Historical era | New Imperialism, First World War, Interwar period, Second World War, Decolonisation of Africa, Cold War | ||||||||

|

• Côte d'Ivoire officially becomes a French colony

|

10 March 1893 | ||||||||

|

• Accession to French West Africa

|

1904 | ||||||||

|

• Ivory Coast becomes an autonomous republic within the French Community

|

December 1958 | ||||||||

|

• Independence from France

|

7 August 1960 | ||||||||

| Currency | French West African franc (1903–1945); West African CFA franc (1945–1960) (XOF) | ||||||||

|

|||||||||

Côte d'Ivoire officially became a French colony on March 10, 1893. Louis Gustave Binger, who had explored the area, became the first governor. He made border agreements with Liberia and Britain (for the Gold Coast). In the early years of French rule, French soldiers went inland to set up new posts. The French settlements faced resistance from local people, even in areas where treaties had been signed. Samori Touré offered the strongest resistance. He had built the Wassoulou Empire across parts of present-day Guinea, Mali, Burkina Faso, and Ivory Coast starting in 1878. Touré's large army could make and fix its own weapons. This helped him gain strong support. Binger fought against Touré's expansion, leading to fierce battles. The French campaigns against the Wassoulou grew stronger in the mid-1890s. They finally captured Touré in 1898.

In 1900, France introduced a head tax to pay for public projects in the colony. This caused several revolts. These public works and using natural resources needed many workers. The French forced adult Ivorian men to work ten days each year without pay. This was seen as a duty to the state. This system was often abused and was the most hated part of French colonial rule. Ivory Coast didn't have enough people to meet the labor needs of French farms and forests. So, the French brought many workers from Upper Volta to Ivory Coast. This forced labor hurt not only the men who had to work but also Ivorian farmers. As farming became more important for Ivory Coast's economy, European and African farmers worked hard to grow their businesses. This created a need for more workers than were available. During World War II, the French government gave European farmers first choice of workers. African farmers had to find volunteers locally or close their businesses. These unfair rules caused big problems between African workers and their European counterparts. Africans had little say because they were not recognized as French citizens. This labor source was so important that in 1932, a large part of Upper Volta was added to Ivory Coast. Many Ivorians saw the head tax as breaking the protection treaties. They felt France was now demanding payment from local kings, instead of the other way around. Many people, especially inland, saw the tax as a shameful sign of being controlled.

From 1904 to 1958, Ivory Coast was part of the Federation of French West Africa. It was a colony and an overseas territory under the French government. Until after World War II, affairs in French West Africa were managed from Paris. France's policy was called "association." This meant all Africans in Ivory Coast were officially French subjects. But they had no right to be represented in government in Africa or France. In 1905, the French officially ended slavery in most of French West Africa.

In 1908, Gabriel Angoulvant became governor of Ivory Coast. Angoulvant believed Ivory Coast could only develop after it was fully conquered, or "pacified." He sent soldiers into the interior to stop resistance. Because of these actions, local rulers had to obey anti-slavery laws. They also had to provide porters and food to French forces. And they had to protect French trade and people. In return, the French agreed to leave local customs alone. They also promised not to interfere in choosing rulers. However, the French often broke their promises. They would send away or imprison rulers who caused trouble. They also grouped villages together and set up a single administration across most of the colony. They replaced the old payment system with allowances based on how well people performed.

French colonial policy had two main ideas: assimilation and association. Assimilation meant that French culture was seen as better than all others. This policy meant spreading the French language, laws, and customs. The policy of association also said French culture was superior. But it meant different rules and systems for the French and the local people. Under this policy, Africans in Ivory Coast could keep their customs if they didn't conflict with French interests. A small group of educated Ivorians, trained in French ways, formed a link between the French and the Africans.

Assimilation was used in Ivory Coast to a small degree. A few Western-educated Ivorians could apply for French citizenship after 1930. But most Ivorians were French subjects with no political rights. They were forced to work in mines, on farms, as porters, and on public projects as part of their tax duty. They also had to serve in the military. They were under a separate legal system for Africans.

During World War II, the Vichy regime controlled Ivory Coast until 1943. Then, General Charles de Gaulle's government took control of all French West Africa. The Brazzaville Conference of 1944 and other meetings after the war led to big government changes in 1946. All African "subjects" were given French citizenship. They gained the right to form political groups. And various types of forced labor were ended. A major change in relations with France happened with the 1956 Overseas Reform Act. This law gave more power from Paris to elected local governments in French West Africa. It also removed remaining unfair voting rules.

Until 1958, governors appointed in Paris ran the colony of Ivory Coast. They used a direct, centralized system. This left little room for Ivorians to help make decisions. The French also used "divide-and-rule" tactics. They only applied assimilation ideas to the educated elite. The French wanted to keep this small but important group happy. This way, they hoped to prevent any anti-French feelings. Even though educated Ivorians strongly disliked the "association" practices, they believed they would become equal to the French through assimilation. They didn't think complete independence from France was the answer. After the postwar reforms, Ivorian leaders realized that assimilation meant the French were seen as superior. They understood that unfair treatment would only end with independence.

Independence

As early as 1944, Charles de Gaulle suggested changing France's colonial policies. In 1946, the French Empire became the French Union. This was later replaced by the French Community in 1958. In December 1958, Ivory Coast became an independent republic within the French Community. This happened after a vote on August 7, which gave community status to all members of the old French West Africa Federation. Only Guinea voted against it. On July 11, 1960, France agreed to Ivory Coast becoming fully independent. Ivory Coast gained independence on August 7, 1960. It made the commercial city of Abidjan its capital.

Ivory Coast's recent political history is closely linked to Félix Houphouët-Boigny. He was the president of the republic and leader of the Democratic Party of Ivory Coast (PDCI) until he died on December 7, 1993. He helped start the Rassemblement Démocratique Africain (RDA). This was the main political party for all French West African territories before independence, except for Mauritania.

Houphouët-Boigny first became well-known in politics in 1944. He founded the African Agricultural Union. This group helped African farmers get better conditions. It also became the core of the PDCI party. After World War II, he was narrowly elected to the first French assembly that wrote a new constitution. He represented Ivory Coast in the French National Assembly from 1946 to 1959. He worked hard on organizing politics across the territories and improving working conditions. After 13 years in the French National Assembly, including almost three years as a minister in the French Government, he became Ivory Coast's first prime minister in April 1959. The next year, he was elected its first president.

In May 1959, Houphouët-Boigny became an even more important figure in West Africa. He led Ivory Coast, Niger, Upper Volta (Burkina Faso), and Dahomey (Benin) to form the Council of the Entente. This was a regional group focused on economic development. He believed that African unity should come through gradual economic and political cooperation. He also believed that countries should not interfere in each other's internal affairs.

Houphouët-Boigny was more traditional than most African leaders after colonialism. He kept close ties with Western countries. He rejected the anti-Western views of many leaders at the time. This helped the country stay economically and politically stable. The first presidential elections with multiple parties were held in October 1990. Houphouët-Boigny won easily. He died on December 7, 1993.

After Houphouët-Boigny

Henri Konan Bédié, who was the President of the Parliament, took over after Houphouët-Boigny. But on December 24, 1999, General Robert Guéï led a military takeover. Guéï was a former army commander whom Bédié had fired. This was the first military takeover in Ivory Coast's history. The economy then slowed down. The military government promised to return the country to democratic rule in 2000.

Guéï allowed elections to be held the next year. When he lost the election to Laurent Gbagbo, Guéï at first refused to accept his defeat. However, street protests forced him to step down. Gbagbo became president on October 26, 2000.

First Civil War

On September 19, 2002, a rebellion started in the north and west of Ivory Coast. The country became divided into three parts. Many people were killed, especially in Abidjan from March 25 to 27. Government forces killed over 200 protesters there. On June 20 and 21, in Bouaké and Korhogo, over 100 people were killed. In 2002, France sent soldiers to Ivory Coast as peacekeepers. A process to bring peace, supported by international groups, began in 2003. In February 2004, the United Nations set up the United Nations Operation in Côte d'Ivoire (UNOCI).

Disarmament was supposed to happen on October 15, 2004, but it failed. Tensions between Ivory Coast and France grew on November 6, 2004. This was after Ivorian air strikes killed 9 French peacekeepers and an aid worker. In response, French forces attacked the airport at Yamoussoukro. They destroyed all airplanes in the Ivorian Air Force. Violent protests broke out in both Abidjan and Yamoussoukro. There was fighting between Ivorians and French peacekeepers. Thousands of foreigners, especially French people, left the two cities. Most of the fighting ended by late 2004. The country was split between a rebel-controlled north, led by Guillaume Soro, and a government-controlled south, led by Laurent Gbagbo.

During this time, the quality of life generally got worse. Debt increased, and there was more unrest. To deal with these problems, the idea of "ivoirité" was created. This was a term that aimed to deny political and economic rights to immigrants from the north. In March 2007, the two sides signed an agreement to hold new elections. However, the elections were delayed until 2010, five years after Gbagbo's term was supposed to end.

Second Civil War

After the country's Independent Electoral Commission (CEI) announced that northern candidate Alassane Ouattara won the 2010 presidential election, the President of the Constitutional Council, who was an ally of Gbagbo, said the results were invalid. He declared that Gbagbo was the winner. Both Gbagbo and Ouattara claimed victory and took the presidential oath of office. The international community, including the United Nations, the African Union, and former colonial power France, supported Ouattara. They called for Gbagbo to step down. However, talks to solve the problem did not work. Hundreds of people died in growing violence between supporters of Gbagbo and Ouattara. At least a million people fled, mostly from Abidjan.

International organizations reported many cases of human rights violations by both sides, especially in Duékoué. The United Nations and French forces took military action to protect their troops and civilians. Ouattara's forces arrested Gbagbo at his home on April 11, 2011.

After the 2011 Civil War

Alassane Ouattara has led Ivory Coast since 2010, when he took power from his predecessor Laurent Gbagbo. Ouattara was re-elected in the 2015 presidential election. In November 2020, he won a third term in the 2020 presidential election. His opponents boycotted the election, saying a third term was against the law. Ivory Coast's Constitutional Council officially confirmed Ouattara's re-election for a third term in November 2020.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Costa de Marfil para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Costa de Marfil para niños

- History of Africa

- History of West Africa

- List of heads of government of Ivory Coast

- List of heads of state of Ivory Coast

- Politics of Ivory Coast

- Abidjan history and timeline

External sources