History of Crete facts for kids

The history of Crete is super old, going back about 9,000 years! Long before the famous Minoan civilization, people lived on this island. The Minoans were actually the very first big civilization in Europe.

After the Minoans, during the Iron Age, Crete had many city-states, like small independent countries, much like in Ancient Greece. Then, over time, Crete became part of the Roman Empire, the Byzantine Empire, the Venetian Republic, and the Ottoman Empire. Finally, it became an independent state before joining modern Greece.

Contents

- Ancient Crete: The Early Days

- Minoan Civilization: Europe's First Great Culture

- Iron Age and Early Greek Cities

- Classical and Hellenistic Crete: City-States and Conflicts

- Roman, Byzantine, and Arab Rule

- Venetian Crete (1205–1669)

- Ottoman Crete (1669–1898)

- Modern Crete

- Other Notable Historical Events

- Images for kids

- See also

Ancient Crete: The Early Days

Scientists found stone tools in southern Crete in 2008–2009 that are at least 130,000 years old! This was a huge surprise because people thought the first sea trips in the Mediterranean happened much later, around 12,000 BC. This discovery suggests that very early humans might have visited Crete a long, long time ago.

For a while, Crete was cut off from other lands. Only a few special animals lived there, like a type of dwarf elephant and a large Cretan owl. Most of these animals are now extinct.

Stone tools also show that hunter-gatherers lived on the island during the Early Holocene period. Around 7000 BC, the Neolithic period began on Crete. This is when people started farming. Early influences on Cretan culture came from nearby islands and from Egypt. People in this period used a special writing system called "Linear A", but we still can't read it!

Archaeologists have found amazing things from ancient Crete, like Minoan palaces, houses, roads, paintings, and sculptures. Some of the earliest farming villages were at Knossos and Trapeza.

Scientists use radiocarbon dating to figure out how old things are. This method suggests that people have lived on Crete for about 130,000 years, though maybe not all the time. Farming culture started around 7000 BC. The first settlers brought animals like cattle, sheep, goats, pigs, and dogs, along with crops like cereals and beans.

At Knossos, under the later Bronze Age palace, remains of a settlement from 7000 BC were found. This was a very large settlement. The animal bones found there show that the early settlers brought their own animals, as most of the large native animals were already gone.

Later in the Neolithic period, more settlements appeared, meaning the population grew. Donkeys and rabbits were brought to the island then. The wild goat called the Kri-kri still has traits from these early domesticated animals.

Minoan Civilization: Europe's First Great Culture

Crete was the heart of Europe's oldest civilization, the Minoans. They used the mysterious Linear A script, and tablets with this writing have been found all over Crete and on some nearby islands like Kea, Kythera, Milos, Rhodes, and especially Thera.

Since we can't read their writing, we learn about the Minoans from their pottery styles. These styles can be matched with pottery from Egypt and the Ancient Near East, helping us figure out their timeline.

Sir Arthur Evans was an archaeologist who famously uncovered the palace at Knossos, the most well-known Minoan site. Other palace sites on Crete, like Phaistos, show amazing stone buildings with many stories. These palaces even had advanced drainage systems, and queens had baths and flushing toilets! Their water engineering was very impressive. Interestingly, these palace complexes did not have defensive walls.

By the 16th century BC, Minoan pottery found on the Greek mainland shows that they had strong connections with people far away. Around that time, a big earthquake caused damage on Crete and Thera, but the Minoans quickly rebuilt everything.

Iron Age and Early Greek Cities

After the Mycenaean civilization fell apart, the first Greek city-states appeared in the 9th century BC. This was also when the famous poems of Homer were written in the 8th century BC. Some of the important Dorian cities that grew on Crete during this time were Kydonia, Lato, Dreros, Gortyn, and Eleutherna.

Classical and Hellenistic Crete: City-States and Conflicts

During the Classical and Hellenistic periods, Crete was a place of fighting city-states that often harbored pirates. In the late 4th century BC, the old aristocratic system started to break down because the rich families kept fighting among themselves. Long wars between the city-states also made Crete's economy weaker.

In the 3rd century BC, cities like Gortyn, Kydonia (Chania), Lyttos, and Polyrrhenia challenged the power of ancient Knossos.

As the cities continued to fight each other, they sometimes asked powerful mainland kingdoms like Macedon or its rivals, Rhodes and Ptolemaic Egypt, to help them. In 220 BC, the island was torn apart by a war between two groups of cities. This led to the Macedonian king Philip V gaining control over Crete. This control lasted until the end of the Cretan War (205–200 BC), when the people of Rhodes and the Romans started to get involved in Cretan affairs. In the 2nd century BC, Ierapytna (Ierapetra) became the most powerful city in eastern Crete.

Roman, Byzantine, and Arab Rule

Around 88 BCE, Mithridates VI Eupator, a ruler from northern Anatolia, started a war against the Roman Republic. He wanted to stop Rome from expanding its power in the Aegean Sea. Mithridates wanted to control Asia Minor and the Black Sea region. He fought several difficult wars, known as the Mithridatic Wars, but he couldn't stop Rome.

In 71 BCE, a Roman general named Marcus Antonius Creticus attacked Crete, saying that Knossos was helping Mithridates. But the Cretans fought back and pushed him away. So, Rome sent Quintus Caecilius Metellus with three armies to the island. After a very tough three-year fight, the Roman army conquered Crete in 69 BCE. Metellus was given the special name "Creticus" for his victory.

Archaeological sites show that there wasn't much damage when Rome took over. Gortyn seemed to be on Rome's side and was rewarded by becoming the capital of the new Roman province called Crete and Cyrenaica.

Later, Rome took over more lands, including the Kingdom of Pontus. This brought almost all of Anatolia under Roman control. Gortyn was also home to the biggest Christian church on Crete, the Basilica of Saint Titus. This church was built in the 1st century CE.

Crete remained a quiet province of the Byzantine Empire (the Eastern Roman Empire) until the 820s CE. Then, Andalusian Muslims led by Abu Hafs took over the island and created a pirate emirate. The city of Gortyn was destroyed, and a new city, Candia (modern Heraklion), built by the Muslims, became the capital.

The Emirate of Crete became a base for Muslim pirates in the Aegean Sea, causing problems for the Byzantines. The Byzantines tried many times to get the island back, finally succeeding in 961 CE. The Byzantine Emperor Nikephoros II Phokas defeated the Muslims and made Crete a Byzantine province again.

The Byzantine Greeks ruled Crete until the Fourth Crusade in 1204. After this crusade, two Italian cities, Genoa and Venice, fought over who would control the island. Venice eventually won and took control by 1212. Even though the local people often rebelled, Venice held onto the island until 1669, when the Ottoman Empire took it over.

Venetian Crete (1205–1669)

After the Fourth Crusade captured Constantinople in 1204, the Byzantine Empire was divided. Crete eventually went to Venice, which ruled it for over 400 years. This period was known as the "Kingdom of Candia".

One of the most important rebellions during this time was the revolt of St. Titus in 1363. Local Cretans and Venetian settlers were tired of Venice's high taxes. They overthrew the Venetian authorities and declared an independent Cretan Republic. It took Venice five years to put down this revolt.

During Venetian rule, the Greek people of Crete were introduced to Renaissance culture. A lively literature developed in the Cretan dialect of Greek. The most famous work from this time is the poem Erotokritos by Vitsentzos Kornaros. Other important Cretan writers and thinkers included Marcus Musurus and Domenicos Theotocopoulos, who became famous as the painter El Greco. He was born in Crete and learned Byzantine art before moving to Italy and Spain.

Ottoman Crete (1669–1898)

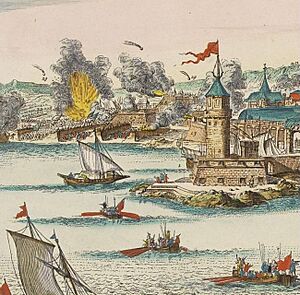

During the Cretan War (1645–1669), the Ottoman Empire pushed Venice out of Crete. Most of the island was lost after the siege of Candia (1648–1669), which might be the longest siege in history. The last Venetian stronghold, Spinalonga, fell in 1718. Crete then became part of the Ottoman Empire for the next two centuries.

There were many big rebellions against Ottoman rule, especially in Sfakia. Daskalogiannis was a famous rebel leader. One big change after the Ottoman conquest was that many people slowly converted to Islam. This gave them tax benefits and other advantages in the Ottoman system. Before the Greek War of Independence, about 45% of the island's population might have been Muslim.

Some Muslims were actually "crypto-Christians," meaning they secretly kept their Christian faith and later converted back. Others left Crete because of the unrest. By the last Ottoman census in 1881, Christians made up 76% of the population, and Cretan Turks were only 24%. Christians were over 90% of the population in most districts, but Muslims were the majority in the three big towns on the north coast.

Greek War of Independence (1821)

The Greek War of Independence started in 1821, and many Cretans joined in. A Christian uprising was met with a harsh response from the Ottomans, and several bishops were executed. The Ottoman Sultan Mahmud II gave control of Crete to Muhammad Ali Pasha, the ruler of Egypt, in exchange for his military help.

Between 1821 and 1828, there was a lot of fighting on the island. Muslims were forced into the large fortified towns on the north coast, and it seems that as many as 60% of them died from plague or famine there. The Cretan Christians also suffered greatly, losing about 21% of their population in the 1830s.

Crete was not included in the new Greek state that was created in 1830. Muhammad Ali's control was confirmed in 1833, but direct Ottoman rule was brought back in 1840.

The island's Christians rebelled several times against Ottoman rule. Revolts in 1841 and 1858 helped them gain some rights, like being allowed to carry weapons, equal worship for Christians and Muslims, and Christian councils to handle education and local laws.

Even with these changes, Christian Cretans still wanted to unite with Greece. Tensions between Christian and Muslim communities were very high. So, in 1866, the great Cretan Revolt began.

This uprising lasted for three years. Volunteers from Greece and other European countries, who felt a lot of sympathy for the Cretans, joined the fight. This was especially true after the terrible event known as the Arkadi Holocaust. Even though the rebels had early successes, pushing the Ottomans into the northern towns, the uprising eventually failed.

The Ottoman leader A'ali Pasha took personal control of the Ottoman forces. He launched a careful campaign to take back the rural areas. He also promised political changes, like a new law that gave Cretan Christians equal (and in practice, majority) control of local government. His plan worked, and the rebel leaders slowly gave up. By early 1869, the island was back under Ottoman control.

During the Congress of Berlin in 1878, there was another rebellion. It was quickly stopped when Britain stepped in and helped create a new constitutional agreement called the Pact of Halepa. Crete became a semi-independent state within the Ottoman Empire, ruled by a Christian Ottoman Governor. In the 1880s, several Christian governors ruled the island, overseeing a parliament where liberals and conservatives argued for power.

Fights between these groups led to another uprising in 1889, and the Halepa Pact broke down. The international powers, annoyed by the constant political fighting, allowed the Ottoman authorities to send troops to the island and restore order. However, they didn't expect the Ottoman Sultan Abdul Hamid II to use this as an excuse to end the Halepa Pact Constitution and rule the island by military law. This made the international community feel more sympathy for the Cretan Christians and made the Cretans even more determined to end Ottoman rule.

When a small uprising started in September 1895, it quickly spread. By the summer of 1896, the Ottoman forces had lost military control of most of the island.

A new Cretan uprising in 1897 led to the Ottoman Empire declaring war on Greece. However, the Great Powers (like France, Italy, Russia, and Great Britain) decided that the Ottoman Empire could no longer control Crete. They sent a multinational naval force, the International Squadron, to Cretan waters in February 1897.

The admirals of this squadron temporarily governed the island. They bombed Cretan rebels, sent sailors and marines ashore, and blocked ports in Crete and Greece. This stopped the organized fighting on the island by late March 1897. Soldiers from five of the powers then occupied key cities in Crete.

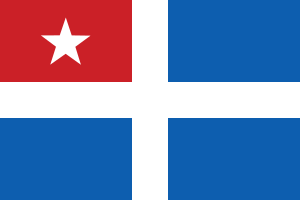

Eventually, the Admirals Council decided to create an autonomous state on Crete within the Ottoman Empire. After a violent riot by Cretan Turks on September 6, 1898, the admirals also decided to remove all Ottoman troops from Crete, which happened on November 6, 1898. When Prince George of Greece arrived in Crete on December 21, 1898, as the first High Commissioner of the autonomous Cretan State, Crete was effectively separated from the Ottoman Empire, even though it was still officially under the Sultan's rule.

Modern Crete

Cretan State

After the Ottoman forces left in November 1898, the autonomous Cretan State was created. It was led by Prince George of Greece and Denmark, and it was still officially under Ottoman rule.

Prince George was replaced by Alexandros Zaimis in 1906. In 1908, taking advantage of problems in Turkey and Zaimis being away, the Cretan leaders declared that they were uniting with Greece. However, other countries didn't officially recognize this until 1913, after the Balkan Wars. At that time, the Treaty of London made the Sultan give up his official rights to the island.

In December 1913, the Greek flag was raised at the Firkas fortress in Chania, with Eleftherios Venizelos and King Constantine present. Crete was finally united with mainland Greece. The Cretan Turks (Muslim minority) initially stayed on the island but were later moved to Turkey as part of a large population exchange agreed upon in the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne between Turkey and Greece.

One of the most important people from the end of Ottoman Crete was the politician Eleftherios Venizelos. He was probably the most important statesman in modern Greece. Venizelos was a lawyer who was active in political groups in Chania, which was then the capital of Crete. After Crete became autonomous, he was first a minister in Prince George's government and then his biggest opponent.

In 1910, Venizelos moved his career to Athens and quickly became a dominant figure in Greek politics. In 1912, after carefully preparing a military alliance against the Ottoman Empire with Serbia, Montenegro, and Bulgaria, he allowed Cretan leaders to join the Greek Parliament. The Ottoman Empire saw this as a reason for war, but the Balkan allies won many big victories in the wars that followed (the Balkan Wars). The Ottoman Empire was largely defeated and forced out of the Balkans and Thrace, except for the borders Turkey still holds today.

World War II

Battle of Greece

In 1939, the United Kingdom promised military help to Greece if its land was threatened. The UK's main goal was to prevent Crete from falling to enemy hands, because the island was important for defending Egypt, the Suez Canal, and the route to India. British troops landed on Crete starting November 3, 1940, with Greece's permission.

The invasion of mainland Greece by the Axis powers began on April 6, 1941. It was over in a few weeks, even with help from Commonwealth armies. King George II and the Greek government had to flee Athens and took refuge in Crete on April 23. Commonwealth troops who escaped from mainland Greece also went to Crete to try and set up a new front.

Battle of Crete

After conquering mainland Greece, Germany turned its attention to Crete. On the morning of May 20, 1941, Crete became the site of the first major airborne attack in history. Nazi Germany launched an invasion called "Operation Mercury." About 17,000 paratroopers were dropped at three important airfields: Maleme, Heraklion, and Rethymnon. Their goal was to capture these airfields so that more German troops could be flown in from mainland Greece, avoiding the British and Greek navies that controlled the seas.

After a fierce and bloody fight between Nazi Germany and the Allies (United Kingdom, New Zealand, Australia, and Greece) that lasted ten days (May 20-31, 1941), the island fell to the Germans.

By June 1, 1941, the Allies had completely left Crete. Even though the Germans won, their elite paratroopers suffered such heavy losses, due to strong resistance from Allied troops and civilians, that Adolf Hitler forbade such large airborne operations for the rest of the war.

The Cretan Resistance

From the very first days of the invasion, the local people of Crete organized a resistance movement. They formed guerrilla groups and intelligence networks. The first resistance groups started in the Cretan mountains as early as June 1941.

In September 1943, a memorable battle happened between German occupation troops and resistance fighters led by "Kapetan" Manolis Bandouvas in the Syme region. Eighty-three German soldiers were killed, and thirteen were taken prisoner. The Germans responded with harsh punishments. German officers regularly used firing squads against Cretan civilians and destroyed villages. Some of the worst atrocities include the massacres at Viannos and Kedros in Amari, and the destruction of Anogeia and Kandanos.

Liberation

By late 1944, German forces were leaving Greece to avoid being trapped by the advancing Russian army. By the end of September, German and Italian troops began pulling out of Crete. A small force of British troops landed on Crete on October 13. Rethymno and Heraklion were liberated as the occupying forces moved to the Chania area.

After VE Day, on May 9, 1945, the German commander on the island, Generalmajor Hans-Georg Benthack, formally surrendered all German forces on Crete to Major-General Colin Callander at the Villa Ariadne at Knossos. The surrender was effective on May 10, 1945.

Civil War

After events in Athens in December 1944, Cretan leftists were targeted by a right-wing group called the National Organization of Rethymno (EOR). This group attacked villages like Koxare and Melampes, and the city of Rethymno, in January 1945. These attacks didn't turn into a full-scale rebellion like on the Greek mainland, and the Cretan ELAS (a leftist group) did not give up its weapons after the Treaty of Varkiza.

The Cretan branch of the Greek Communist Party (KKE) knew that the island wasn't good for a long rebellion because it was isolated from the mainland and because many people supported Venizelism (a liberal political movement) and conservative ideas. The presence of many bandits, escaped prisoners, and army deserters in the countryside also made things complicated.

An uneasy peace lasted until 1947, with several arrests of important communists in Chania and Heraklion. This was followed by the widespread arming of right-leaning villagers and the creation of the first Cretan Rural Security Units, led by Bandouvas in Heraklion and "Kapetan" Gyparis in Chania.

Encouraged by orders from their main organization in Athens, the KKE started a rebellion in Crete, marking the beginning of the Greek Civil War on the island. In eastern Crete, the Democratic Army of Greece (DSE) struggled to gain a foothold in Dikti and Psilorites. They constantly clashed with local bandits, armed farmers, and army units. The hot summer limited water sources for the rebels, making it harder for them to move around. On July 1, 1947, the remaining 55 DSE fighters were ambushed south of Psilorites while trying to move to Mount Kedros. Their commander, Giannis Podias, was killed, and the few survivors joined the rest of the DSE in Lefka Ori.

The Lefka Ori region in the west offered better conditions for the DSE's rebellion. In the summer of 1947, the DSE raided the Maleme Airport, stealing from its warehouses and kidnapping 100 airmen from the Royal Hellenic Air Force. Twelve of these airmen joined the rebels. On July 4, 1947, the DSE attacked a former German motor depot at Chrysopigi, near Chania. They kidnapped the guards, looted the warehouse, and set it on fire, causing a big explosion that led to government troops being sent all over the island.

After the DSE units in the east were destroyed, the Cretan DSE had about 300 fighters. A bad harvest in 1947 caused food shortages in Crete, which were much worse for the rebels who couldn't get supplies from cities. The communists resorted to stealing cattle and took a lot of potatoes from the village of Lakkoi. This only solved their supply problems for a short time. The communists also struggled to keep their recruits disciplined or to remove the mountain bandits in the areas they supposedly controlled.

In the autumn of 1947, the Greek government offered generous amnesty terms to Cretan DSE fighters and mountain bandits. Many of them chose to stop fighting or even switch sides to the nationalists. On July 4, 1948, government troops launched a large attack on Samariá Gorge. Many DSE soldiers were killed in the fighting, while the survivors broke into small armed groups. In October 1948, the secretary of the Cretan KKE, Giorgos Tsitilos, was killed in an ambush. By the next month, only 34 DSE fighters were still active in Lefka Ori. The rebellion in Crete slowly died out, with the last two holdouts surrendering in 1974, 25 years after the war ended on mainland Greece.

Other Notable Historical Events

Cretan School of Art

An important style of icon painting, which mixed Byzantine art with Latin influences, grew popular while Crete was under Venetian rule during the late Middle Ages. It became very strong after the Fall of Constantinople, becoming the main style of Greek painting in the 15th, 16th, and 17th centuries.

Cretan Literature

Because of the economic and intellectual growth in Crete during the Venetian era, Cretan literature was rich and important for the future of modern Greek literature. Peaceful living and contact with a developed cultural people helped education and literature grow, leading to many remarkable literary works.

The Black Death

During the time of the Black Death plagues, many Cretans moved overseas during difficult times on the island. Some of them became very rich abroad, like Constantine Corniaktos (around 1517–1603), who became one of the wealthiest people in Eastern Europe.

Images for kids

-

The Bull-Leaping Fresco from Knossos showing bull-leaping, c. 1450 BC. The dark-skinned figure is likely a man, and the two light-skinned figures are probably women.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Creta para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Creta para niños

- Cretan Revolt

- History of Greece

- List of rulers of Crete