History of Malta facts for kids

Malta has a very long and interesting history! People first lived on the islands around 5900 BC. These early settlers were farmers. Their farming methods eventually made the soil poor, and the islands became too dry to live on.

Around 3850 BC, new people arrived and settled. This civilization built the amazing Megalithic Temples. These temples are some of the oldest buildings still standing in the world today! Their civilization ended around 2350 BC, but new groups of Bronze Age warriors soon came to Malta.

Malta's very early history ended around 700 BC. This is when the Phoenicians, who were great sailors and traders, came and took control of the islands. They ruled until 218 BC, when the Roman Republic took over. Later, in the 6th century AD, the Byzantines (Eastern Romans) controlled Malta.

In 870 AD, the Aghlabids (Muslims from North Africa) took over after a siege. Malta might have been almost empty for a few centuries. Then, in the 11th century, Arabs repopulated the islands. In 1091, the Normans from County of Sicily invaded, and the islands slowly became Christian again. Malta then became part of the Kingdom of Sicily and was ruled by different groups like the Swabians, Aragonese, and finally the Spanish.

In 1530, the islands were given to the Order of St. John. They ruled Malta as a small state connected to Sicily. In 1565, the Ottoman Empire tried to capture Malta in the Great Siege of Malta, but the Knights and the Maltese people fought them off. The Order ruled Malta for over 200 years. During this time, art and buildings flourished, and society improved. The French, led by Napoleon Bonaparte, invaded in 1798, ending the Knights' rule and starting the French occupation of Malta.

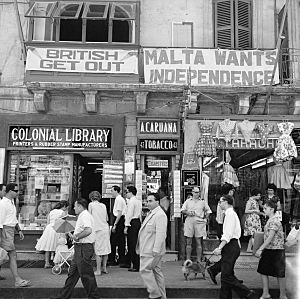

After a few months of French rule, the Maltese people rebelled and forced the French out in 1800. Malta then became a British protectorate, and by 1813, it was a British colony. The islands became a very important naval base for the British, especially for their fleet in the Mediterranean Sea. In the late 1800s, technology and finance grew. For example, the Anglo-Egyptian Bank opened in 1882, and the Malta Railway started in 1883. In 1921, Malta gained some self-government from London. This meant they had their own parliament with two parts.

During World War II, British forces in Malta were heavily attacked by Italian and German planes. But the British and Maltese bravely held strong. In 1942, the island was given the George Cross, a very high award for bravery. Today, the George Cross is on Malta's flag and coat of arms.

In 1964, Malta became an independent country called the State of Malta, part of the British Commonwealth. In 1974, it became a republic. Since 2004, Malta has been a member of the European Union.

Contents

- Malta's Land and Past Environments

- Early Settlers: Neolithic Period (5900 BC–3850 BC)

- The Temple Builders (3850 BC–2350 BC)

- The Bronze Age (2350 BC–700 BC)

- Ancient Times

- The Middle Ages

- Rule by the Knights of St. John (1530–1798)

- French Occupation (1798–1800)

- Malta in the British Empire (1800–1964)

- Independent Malta (since 1964)

- See also

Malta's Land and Past Environments

Malta sits on an underwater ridge that connects North Africa to Sicily. Long ago, Malta was underwater, which we know because of fossils of sea creatures found in rocks on the highest parts of the island. As the land pushed up and the Strait of Gibraltar closed, the sea level dropped. Malta then became a land bridge between two continents, surrounded by large lakes. In some caves in Malta, scientists have found bones of elephants, hippopotamuses, and other large animals. Some of these animals are now found in Africa, while others are native to Europe.

Early Settlers: Neolithic Period (5900 BC–3850 BC)

Scientists used to think Malta's first people arrived around 5700 BC. But new studies of old soils show they arrived earlier, around 5900 BC. These first Neolithic people were thought to come from Sicily, which is about 100 kilometers (62 miles) north. However, DNA tests now show they came from different parts of the Mediterranean, including both Europe and Africa.

These early communities mainly farmed and fished, with some hunting. They lived in caves and simple open homes. Over time, they had contact with other cultures, which influenced their pottery designs and colors. Their farming methods made the soil poor. At the same time, a long period of dry weather began. The islands became too dry to support farming. This was partly due to climate change. Because of this, the islands were empty for about 1,000 years.

Research shows that climate changes made Malta unlivable at certain times in prehistory. There was a big gap of about 1,000 years between the first settlers and the next group. This second group settled permanently and eventually built the famous megalithic temples.

The Temple Builders (3850 BC–2350 BC)

A second group of people arrived from Sicily around 3850 BC. It's amazing that this second group lived on Malta for 1,500 years, especially since the land was slowly getting worse. This kind of long-lasting settlement is rare in Europe.

One of the most famous times in Malta's history is the Temple Period, which began around 3600 BC. The Ġgantija Temple in Gozo is one of the oldest free-standing buildings in the world. Its name comes from the Maltese word ġgant, meaning "giant," because of its huge size. Many of these temples have five half-circle rooms connected in the middle. Some think these rooms might have represented the head, arms, and legs of a god. Many statues found in these temples are of large human figures, often called "fat ladies." People believe these statues represent fertility.

The civilization that built these temples lasted about 1,500 years, until around 2350 BC. At this point, their culture seems to have disappeared. Scientists wonder what happened to them, but it's thought that climate change and drought caused their collapse. We can learn from the mistakes of these early Maltese people. Not enough water and damaged soil can cause a civilization to fail. The second group of settlers managed their resources well for over 1,500 years. They only failed when climate conditions and drought became too extreme.

The Bronze Age (2350 BC–700 BC)

After the Temple Period came the Bronze Age. From this time, we have remains of settlements and villages. There are also dolmens, which are altar-like structures made from huge stone slabs. These seem to belong to a different group of people than those who built the temples. It's thought they came from Sicily because their buildings are similar to those found there.

One surviving menhir, a tall standing stone used to build temples, is still in Kirkop. It's one of the few still in good condition.

Some of the most interesting and mysterious things from this time are the "cart ruts." You can see them at a place called Misraħ Għar il-Kbir (also known as Clapham Junction). These are pairs of parallel channels cut into the rock, stretching for long distances, often in a straight line. No one knows exactly what they were used for. One idea is that animals pulled carts along them, and the channels guided the carts. The society that built these structures eventually disappeared.

Between 1400 BC and 1200 BC, Malta was influenced by the Mycaenaean culture, as shown by Mycaenaean artifacts found there.

Ancient Times

Phoenicians and Carthaginians

The Phoenicians, possibly from Tyre, started to settle in Malta around the early 8th century BC. They used Malta as a base to explore and trade in the Mediterranean Sea. Phoenician tombs found in Rabat, Malta and Victoria (on Gozo) suggest that the main towns were present-day Mdina on Malta and the Cittadella on Gozo. The settlement on Malta was called Maleth, meaning "safe haven," and the whole island became known by that name.

Malta came under the control of Carthage around the mid-6th century BC. Carthage was another powerful trading empire. By the late 4th century BC, Malta was an important trading stop connecting southern Italy and Sicily to North Africa. This led to the introduction of Hellenistic (Greek-like) styles in buildings and pottery. Greek language also started to be used, as shown by the Cippi of Melqart, which had writing in both Phoenician and Greek. These stones later helped scholars understand the ancient Phoenician alphabet.

In 255 BC, the Romans attacked Malta during the First Punic War, causing a lot of damage.

Roman Rule

According to the Roman historian Livy, the Romans took control of Malta at the start of the Second Punic War in 218 BC. The Carthaginian commander on the island surrendered without a fight. Malta became part of the Roman province of Sicily. But by the 1st century AD, Malta had its own senate and assembly. Both Malta and Gozo even made their own coins.

During Roman times, the Punic city of Maleth became known as Melite. It was the main administrative center. The city grew to its largest size, covering all of modern-day Mdina and large parts of Rabat. Remains show that the city had strong defensive walls. An impressive house called the Domvs Romana has been dug up, showing beautiful Roman mosaics. This house likely belonged to a rich Roman noble.

Malta did well under Roman rule. Latin became the official language, and Roman religion was introduced. However, the local Punic-Hellenistic culture and language probably lasted until at least the 1st century AD.

In AD 60, the Acts of the Apostles in the Bible says that Saint Paul was shipwrecked on an island called Melite. Many believe this was Malta. There's a tradition that the shipwreck happened in St. Paul's Bay. In the Bible, the islanders welcome Paul. When a snake bites him, he is unharmed, leading the people to believe he is a god. This gave Paul a chance to share the Christian message.

Malta remained part of the Roman Empire until the early 6th century AD.

The Middle Ages

Byzantine Rule

In 533, the Byzantine general Belisarius might have stopped in Malta on his way to North Africa. By 535, Malta was part of the Byzantine province of Sicily. During this time, the main towns were Melite on Malta and the Citadel on Gozo. Places like Marsaxlokk and Marsa were likely used as harbors. Many Byzantine pottery pieces found in Malta suggest the island was important to the empire from the 6th to 8th centuries.

From the late 7th century, the Mediterranean faced threats from Muslim expansion. The Byzantines likely improved Malta's defenses. For example, defensive walls were built around the church at Tas-Silġ around the 8th century.

Arab Period

In 870 AD, Muslims from North Africa took over Malta. They besieged the Byzantine city of Melite. After the city fell, its people were killed, the city was destroyed, and its churches were looted. Marble from Melite's churches was even used to build a castle in Tunisia.

Some historians believe Malta was almost empty until around 1048 or 1049. Then, a Muslim community and their slaves rebuilt the city of Melite as Medina, making it "a finer place than it was before." However, other evidence suggests Medina was already a busy Muslim town by the early 11th century. In 1053–54, the Byzantines tried to take Medina but were pushed back.

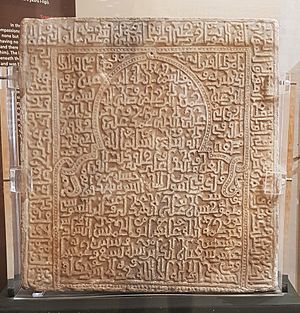

Even though their rule was relatively short, the Arabs had a big impact on Malta. They brought their language, Siculo-Arabic, which later became the basis for the Maltese language. They also introduced cotton, oranges, lemons, and new ways of watering crops. Some of these, like the noria (a waterwheel), are still used today. Many place names in Malta come from this period.

For a long time, historians debated whether Christians continuously lived in Malta during Muslim rule. Some believed a Christian community always existed. However, other historians argue that Malta was mostly Muslim-inhabited after 870 AD. The fact that the Maltese language is mostly based on Arabic, with very few older words, suggests a big change in the population.

Norman Rule and the Kingdom of Sicily

Malta returned to Christian rule with the Norman conquest. In 1091, Count Roger I of Sicily invaded Malta. He made the island's Muslim rulers his vassals, meaning they had to pay tribute to him. In 1127, his son Roger II of Sicily fully established Norman rule, leading to the islands becoming Christian again.

Malta was part of the Kingdom of Sicily for almost 440 years. During this time, Malta was sold and resold to different feudal lords. It was ruled by the Swabians, Anjou, the Crown of Aragon, the Crown of Castile, and finally Spain. In 1479, the Crown of Aragon joined with Castile, and Malta became part of the Spanish Empire.

The islands remained largely Muslim-inhabited for a long time after the end of Arab rule. The Arab way of governing stayed in place, and Muslims were allowed to practice their religion freely until the 13th century. The Normans even allowed a Muslim emir (ruler) to stay in power, as long as he paid them a yearly tribute. Because of this, Muslims continued to be the main population and economic force in Malta for at least 150 years after the Christian conquest.

In 1122, there was a Muslim uprising in Malta. In 1127, Roger II of Sicily reconquered the islands. Even in 1175, a visitor from Germany thought Malta was mostly or entirely inhabited by Muslims.

In 1192, Tancred of Sicily made Margaritus of Brindisi the first Count of Malta. Between 1194 and 1530, the Kingdom of Sicily ruled Malta. During this time, Malta slowly became more Roman and Latin in culture, and Roman Catholicism became firmly established. However, a strong Muslim part of society remained until 1224.

In 1224, Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor, sent an army to Malta. He wanted to make sure the Muslim population didn't help a Muslim rebellion in Sicily.

After the Norman conquest, Malta's population grew, mainly from people moving from Sicily and Italy. For example, in 1223, all the men from the Italian town of Celano were sent to live in Malta. In 1240, a Norman and Sicilian army was stationed there. Also, noble families from Sicily settled in Malta between 1372 and 1450. Because of this, studies show that modern Maltese men likely came from Southern Italy, including Sicily.

Around 1249, some Maltese Muslims were sent to an Italian colony for Sicilian Muslims called Lucera. Some historians believe this marked the end of Islam in Malta. However, the Maltese language, which is based on Arabic, survived. This suggests that many Christians already spoke Maltese, or that many Muslims converted to Christianity and stayed.

In 1266, Malta was given to Charles of Anjou, the brother of King Louis IX of France. Charles was not tolerant of religions other than Roman Catholicism. However, Malta still had strong connections with Africa until the Aragonese and Spanish rule began in 1283.

In September 1429, Saracens from the Hafsid dynasty tried to capture Malta but were pushed back by the Maltese. The invaders robbed the countryside and took about 3,000 people as slaves.

By the end of the 15th century, all Maltese Muslims were forced to convert to Christianity. They had to change their names to sound more Latin or adopt new surnames to hide their past identities.

Rule by the Knights of St. John (1530–1798)

Malta was ruled by the Order of Saint John from 1530 to 1798. They were a vassal state of the Kingdom of Sicily.

Early Years of the Knights

In the early 1500s, the Ottoman Empire was growing powerful. The Spanish king Charles V worried that if Rome fell to the Ottomans, it would be the end of Christian Europe. In 1522, Suleiman I had driven the Knights Hospitaller out of Rhodes. These Knights then spread out across Europe. To protect Rome from an attack from the south, Charles V gave Malta to the Knights in 1530.

For the next 275 years, these famous "Knights of Malta" made the island their home. They made Italian language the official language. They built towns, palaces, churches, gardens, and strong forts. They filled the island with beautiful art and improved its culture.

The Order of the Knights of St. John was first created to help pilgrims traveling to the Holy Land. Because of many battles, one of their main jobs became providing medical help. Even today, their eight-pointed cross is used by ambulances and first aid groups. To defend the pilgrims and the lands they gained, the Knights also became a strong military force. Over time, the Order became powerful and wealthy. They were known as skilled sailors.

From Malta, the Knights continued to attack Ottoman ships. Soon, Sultan Suleyman the Magnificent decided to launch a final attack on the Order. By this time, the Knights had settled in the city of Birgu, which had excellent harbors for their ships. Birgu was one of the two main towns then, the other being Mdina, the old capital. The defenses around Birgu were strengthened, and new forts were built on the other side, where Senglea now stands. A small fort called Fort Saint Elmo was built at the tip of the peninsula where Valletta is today.

The Great Siege

On May 18, 1565, Suleiman the Magnificent began his siege of Malta. The Knights were as ready as they could be. First, the Ottomans attacked the new Fort St. Elmo. After a month of fierce fighting, the fort was destroyed, but the soldiers fought until the end. After this, the Ottomans attacked Birgu and the forts at Senglea, but they couldn't capture them.

The long siege ended on September 8 of the same year. The Ottoman Empire gave up because winter storms were coming, which would prevent their ships from leaving. The Ottomans had expected an easy victory within weeks. They had 40,000 men against the Knights' 9,000, most of whom were Maltese soldiers and ordinary citizens. Losing thousands of men was very discouraging for them. The Ottomans never tried to conquer Malta again, and the Sultan died the next year.

After the Siege

The year after the siege, the Order began building a new city with incredibly strong fortifications on the Sciberras Peninsula, which the Ottomans had used as a base. It was named Valletta after Jean Parisot de Valette, the Grand Master who led the Order to victory. Since the Ottoman Empire never attacked again, the fortifications were never tested in battle. Today, they are some of the best-preserved forts from that time.

Unlike other rulers of the island, the Order of St. John didn't have a "home country" outside Malta. The island became their true home, so they invested more in it than any other power. Its members came from noble families, and the Order had become very rich from helping pilgrims. The buildings and art from this period are among the greatest in Malta's history, especially in their "prize jewel"—the city of Valletta.

However, as their main reason for existing (helping pilgrims and fighting Ottomans) lessened, the Order's best days were over. In the last 30 years of the 1700s, the Order slowly declined. This was partly because some of the last Grand Masters spent too much money, draining the Order's finances. Because of this, the Order also became unpopular with the Maltese people.

In 1775, a revolt called the Rising of the Priests happened. Rebels managed to capture Fort St Elmo, but the revolt was stopped. Some leaders were executed, while others were imprisoned or sent away.

French Occupation (1798–1800)

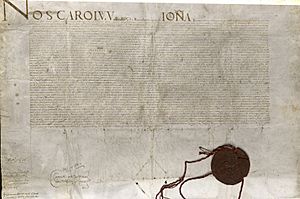

Over the years, the Knights' power weakened. Their rule ended in 1798 when Napoleon Bonaparte's fleet stopped in Malta on its way to Egypt. Napoleon asked for a safe harbor to resupply his ships. When the Knights refused to give him water, Napoleon sent soldiers to climb the hills of Valletta. Grand Master Hompesch surrendered on June 11. The next day, a treaty was signed, giving control of Malta to the French Republic.

During his very short stay (only six days), Napoleon made many changes. He created a new government, set up twelve local councils, and organized public finances. He also ended all old feudal rights and privileges, abolished slavery, and freed all Turkish slaves (about 2,000). In terms of law, a family code was created, and twelve judges were appointed. Public education was organized, with primary and secondary schools. Fifteen primary schools were founded, and the university was replaced by a new school with scientific subjects like math, physics, and navigation.

Napoleon then sailed for Egypt, leaving a large group of soldiers in Malta. At first, the Maltese people were hopeful about the French because the Knights had become unpopular. But this hope didn't last long. Within months, the French started closing convents and taking church treasures. The Maltese people rebelled, and the French soldiers retreated into Valletta. After locals tried and failed to retake Valletta, they asked the British for help. Rear Admiral Lord Horatio Nelson decided to completely block Valletta in 1799. The French soldiers surrendered in 1800.

Malta in the British Empire (1800–1964)

British Malta in the 19th and Early 20th Centuries

In 1800, Malta willingly became part of the British Empire as a protectorate. The 1802 Treaty of Amiens said Britain should leave the island, but they didn't. This was one reason why war started again between Britain and France.

At first, the island wasn't seen as very important. But its excellent harbors became very valuable to the British, especially after the Suez Canal opened in 1869. Malta became a military and naval fortress, serving as the main base for the British Mediterranean fleet.

The Maltese people were not given full self-rule until 1921, though a partly elected council was created in 1849. Locals sometimes faced great poverty. This was because the island was overpopulated and depended on British military spending, which changed with wars. Throughout the 1800s, the British made some liberal changes to the government. These were often resisted by the Church and the Maltese elite, who wanted to keep their old privileges. Political groups, like the Nationalist Party, were formed to protect the Italian language in Malta.

In 1813, Malta received the Bathurst Constitution. In 1814, it was declared free of the plague. The 1815 Congress of Vienna confirmed British rule under the 1814 Treaty of Paris. In 1819, the local Italian-speaking Università (a governing body) was dissolved.

In 1839, press censorship was ended. In 1849, a Council of Government with elected members was set up under British rule. In 1881, an Executive Council was created. In 1887, the Council of Government was given "dual control" under British rule.

The late 1800s saw technical and financial progress. The Anglo-Egyptian Bank was founded in 1882, and the Malta Railway began operating in 1883. The first postage stamps were issued in 1885, and tram service began in 1904. In 1886, Surgeon Major David Bruce discovered the microbe that caused Malta Fever. In 1905, Themistocles Zammit found the sources of the fever. In 1912, Dun Karm Psaila wrote his first poem in Maltese.

Between 1915 and 1918, during World War I, Malta was known as "the Nurse of the Mediterranean." This was because many wounded soldiers were cared for in Malta.

Malta Between the World Wars

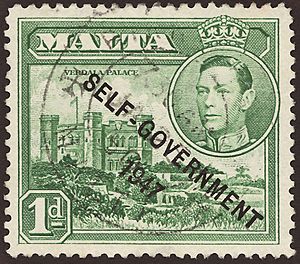

In 1919, the Sette Giugno (June 7) riots happened because bread prices were too high. These riots led to more self-rule for the Maltese in the 1920s. After a National Assembly was called, Malta was granted self-government under British rule in 1921. Malta got a bicameral parliament with a Senate (which was later removed in 1949) and an elected Legislative Assembly. Joseph Howard became Prime Minister. In 1923, the Innu Malti (Maltese National Anthem) was played publicly for the first time.

The 1930s were a time of problems between Maltese politicians, the Catholic Church, and the British. The 1921 Constitution was stopped twice. First, in 1930–1932, because of a conflict between the ruling party and the Church. The Church told people it was a serious sin to vote for that party, making fair elections impossible. Again, in 1933, the Constitution was removed because the government wanted to spend money on teaching Italian in elementary schools. So, Malta went back to being a direct British colony, like it was in 1813.

Before the British arrived, Italian had been the official language for the educated people since 1530. But the British increased the use of English. In 1934, Maltese was declared an official language, making three official languages. Two years later, in 1936, a new law said that Maltese and English were the only official languages. This finally settled the "Language Question" that had been a big political issue for over 50 years. In 1934, only about 15% of the population could speak Italian well.

British Malta During World War II

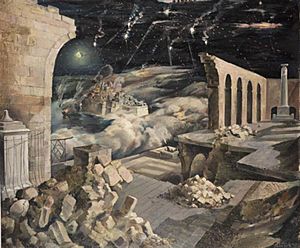

Before World War II, Valletta was the main base for the Royal Navy's Mediterranean Fleet. However, the command was moved to Egypt in April 1937, because people worried it was too vulnerable to air attacks from Europe. When Italy declared war on June 10, 1940, Malta had fewer than four thousand soldiers and only about five weeks of food for its population of around three hundred thousand. Malta's air defenses had about 42 anti-aircraft guns and four Gloster Gladiator planes.

Because it was a British colony and close to Sicily (controlled by the Axis Powers), Malta was heavily bombed by Italian and German air forces. The British used Malta to launch attacks on the Italian navy and had a submarine base there. It was also used to listen to German radio messages, including secret Enigma codes.

The first air raids on Malta happened on June 11, 1940, with six attacks that day. Initially, Italian bombers flew very high, then dropped lower to improve accuracy. Despite some early misses, Italian bombing became more accurate, causing much damage to military and civilian buildings. However, any damage was usually repaired quickly before new bombers could attack.

By the end of August, the Gladiators were joined by twelve Hawker Hurricane planes. During the first five months of fighting, Malta's aircraft destroyed or damaged about 37 Italian planes. An Italian pilot said, "Malta was really a big problem for us—very well-defended." Still, the Italian bombing caused serious damage to the island's buildings and made it harder for the Royal Navy to operate in the Mediterranean.

By December 1941, 330 people in Malta had been killed and 297 seriously wounded. In January 1941, German air forces arrived in Sicily. Over the next four months, 820 people were killed and 915 seriously wounded.

On April 15, 1942, King George VI awarded the George Cross (the highest civilian award for bravery) "to the island fortress of Malta — its people and defenders." Franklin D. Roosevelt visited on December 8, 1943, and gave a United States Presidential Citation to the people of Malta. Part of it read: "Under repeated fire from the skies, Malta stood alone and unafraid in the centre of the sea, one tiny bright flame in the darkness – a beacon of hope for the clearer days which have come." This full citation is now on a plaque in Valletta.

In 1942, a convoy of ships called Operation Pedestal was sent to bring supplies to Malta. Five ships, including the tanker SS Ohio, made it to the Grand Harbour, bringing enough supplies for Malta to survive. The next year, Franklin D. Roosevelt and Winston Churchill visited Malta. King George VI also visited.

In 1943, the Allies launched the invasion of Sicily from Malta. The invasion was planned from the Lascaris War Rooms in Valletta. After Italy surrendered later in 1943, a large part of the Italian Navy surrendered to the British in Malta.

The Malta Conference was held in 1945, where Churchill and Roosevelt met before their meeting with Joseph Stalin.

The 1946 National Assembly led to a new constitution in 1947. This gave Malta self-government back, with Paul Boffa as Prime Minister. On September 5, 1947, women in Malta were given the right to vote. That year, Agatha Barbara was the first woman elected as a Maltese Member of Parliament.

From Self-Rule to Independence

After World War II, Malta gained self-rule. The Malta Labour Party (MLP) led by Dom Mintoff wanted either full integration with the UK or complete independence. The Partit Nazzjonalista (PN) led by George Borg Olivier preferred independence, similar to countries like Canada and Australia.

In 1955, after the MLP won the election, talks were held in London about Malta's future. The British government agreed to offer Malta its own representation in the British Parliament, with three seats. The Maltese Parliament would control all matters except defense, foreign policy, and taxes. Maltese people were also promised social and economic equality with the UK.

A referendum on integration with the UK was held in February 1956. 77.02% of voters were in favor. However, the Nationalist Party and the Church boycotted the vote, so only 59.1% of people voted, making the result unclear.

Malta's importance to the Royal Navy was decreasing. The British government was less willing to keep the naval dockyards. When the Admiralty decided to fire 40 workers at the dockyard, Mintoff declared that the Maltese people were "no longer bound by agreements" with the British government. In protest, Dom Mintoff and all MLP members of parliament resigned on April 21, 1958. This led to the British Governor declaring a state of emergency, suspending the constitution, and placing Malta under direct British rule. The MLP now fully supported independence from Britain.

From 1959, Malta's British governor started a plan to boost the economy by promoting tourism and offering low tax rates to attract British retirees.

In 1961, a new constitution allowed for some self-government and recognized Malta as a "State." Giorgio Borg Olivier became Prime Minister the next year.

Independent Malta (since 1964)

Nationalist Governments (1964–1971)

After the Malta Independence Act 1964 was passed by the British Parliament, and a new Maltese constitution was approved by voters, the State of Malta was formed on September 21, 1964. It became an independent constitutional monarchy, with Elizabeth II as Queen of Malta and head of state. This day is still celebrated every year as Independence Day, a national holiday. On December 1, 1964, Malta joined the United Nations.

In the first two elections after independence, in 1962 and 1966, the Nationalist Party won the most seats in Parliament. During these years, relations with Italy were very important for Malta to gain independence and connect with Europe. Malta signed four cooperation agreements with Italy in 1967.

In 1965, Malta joined the Council of Europe. In 1970, Malta signed a treaty to associate with the European Economic Community.

Labour Governments (1971–1987)

The elections of 1971 saw the Labour Party (MLP) led by Dom Mintoff win by a small number of votes. The Labour government immediately started to re-negotiate military and financial agreements with the United Kingdom. The government also began to take control of industries and expand the public sector and welfare state. Laws about work were updated, and gender equality was introduced in salary pay. The next year, Malta signed a Military Base Agreement with the United Kingdom and other NATO countries.

Through some changes to the constitution, Malta became a republic on December 13, 1974. The last Governor-General, Sir Anthony Mamo, became its first President. A law passed the next year removed all titles of nobility in Malta.

The Labour Party won again in the 1976 elections. Between 1976 and 1981, Malta faced tough times. The Labour government asked the Maltese people to make sacrifices to overcome the difficulties. There were shortages of basic goods, and water and electricity were often cut off for days. Political tensions grew.

End of British Presence and Relations with Libya and Italy

On April 1, 1979, the last British forces left the island. This is celebrated as Freedom Day on March 31. Celebrations begin with a ceremony in Floriana near the War Memorial. A popular event on this day is the traditional regatta (boat race) in the Grand Harbour.

Under Mintoff's leadership, Malta began to build close cultural and economic ties with Muammar Gaddafi's Libya. They also formed diplomatic and military ties with North Korea.

During the Mintoff years, Libya loaned Malta millions of dollars to make up for the money lost when British military bases closed. These closer ties with Libya meant a big, but short-lived, change in Malta's foreign policy. Western media reported that Malta seemed to be turning away from NATO, the UK, and Europe. History books started to suggest a break between Italian and Catholic populations, and instead promoted closer cultural ties with North Africa.

Malta and Libya signed a Friendship and Cooperation Treaty. For a short time, Arabic became a required subject in Maltese secondary schools. In 1984, the Mariam Al-Batool Mosque was officially opened in Malta by Muammar Gaddafi.

In 1980, an oil rig drilling for the Maltese government had to stop operations after being threatened by a Libyan gunboat. Both Malta and Libya claimed rights to the area. The issue was taken to the International Court of Justice in 1982.

In 1980, Malta signed a neutrality agreement with Italy. Under this agreement, Malta promised not to join any military alliances, and Italy agreed to protect Malta's neutrality. Malta's relations with Italy have been described as "generally excellent."

Constitutional Crisis in the 1980s

The 1981 general elections saw the Nationalist Party (NP) win the most votes. However, the Labour Party won more parliamentary seats due to the voting system, and Mintoff remained Prime Minister. This led to a political crisis. The Nationalists, now led by Eddie Fenech Adami, refused to accept the election result and did not take their seats in parliament for the first years. They demanded that Parliament should truly represent the people's vote. Despite this, the Labour government stayed in power for its full five-year term. Mintoff resigned as Prime Minister and party leader in 1984, and Karmenu Mifsud Bonnici took over.

The years under Mifsud Bonnici were marked by political tensions and violence. After a five-year debate, Fenech Adami and Mintoff reached an agreement to improve the constitution. Changes were made in January 1987. These changes guaranteed that the party with the most votes would also get the most parliamentary seats to govern. This paved the way for the Nationalist Party to return to government later that year.

Joining the European Union (1987–2004)

The general elections in 1987 saw the Nationalist Party win with a majority of votes. The new Nationalist government, led by Edward Fenech Adami, worked to improve Malta's ties with Western Europe and the United States. The Nationalist Party wanted Malta to join the European Union and applied on July 16, 1990. This became a big issue, with the Labour party opposing membership.

A large program of economic changes and public investments led to the Nationalists winning again with a larger majority in the 1992 elections. In 1993, local councils were brought back in Malta.

General elections were held in Malta on October 26, 1996. Although the Labour party received the most votes, the Nationalists won more seats. The 1987 constitutional changes had to be used again, and the Labour Party was given four extra seats to ensure they had a majority in Parliament. Malta's application to join the EU was then paused.

A disagreement within the Labour Party in 1998 led to the government losing its majority. This resulted in early elections.

When the Nationalist Party returned to office in the 1998 elections with a large lead, they restarted the EU membership application. Malta was officially accepted as a candidate country in December 1999. In 2000, the death penalty was removed from Malta's military laws.

Negotiations to join the EU finished in late 2002. A referendum on membership in 2003 showed that 53.65% of voters said "yes." The Labour party said they would not be bound by this result if they won the next election. However, elections were called, and the Nationalist Party, led by Prime Minister Fenech Adami, won another term. In April 2004, Eddie Fenech Adami became President of Malta. Lawrence Gonzi took over as Prime Minister. The treaty to join the EU was signed, and Malta joined the EU on May 1, 2004. Later, both major parties agreed on EU membership. Joe Borg was appointed as the first Maltese European commissioner.

Malta in the European Union (2004–Present)

Malta joining the European Union in 2004 had big effects on its foreign policy. For example, Malta had to leave the Non-Aligned Movement, which it had been an active member of since 1971.

As part of its EU membership, Malta joined the Eurozone on January 1, 2008. The 2008 election confirmed Gonzi as Prime Minister. In 2009, George Abela became President of Malta.

On May 28, 2011, the Maltese voted "yes" in a referendum on divorce. At that time, Malta was one of only three countries in the world where divorce was not allowed. Because of the referendum result, a law allowing divorce under certain conditions was passed that same year.

A snap election was called for March 2013 after the Gonzi government lost its majority in Parliament. The Nationalist Party lost the election after being in power for more than 15 years since 1987 (except for a short period from 1996 to 1998). Labour Party leader Joseph Muscat was elected as Prime Minister.

In April 2019, the parliament elected George Vella as the 10th President of the Republic of Malta, succeeding Marie-Louise Coleiro Preca.

In March 2022, the ruling Labour party, led by Prime Minister Robert Abela, won its third election in a row. They achieved an even bigger victory than in 2013 and 2017.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Malta para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Malta para niños

- Culture of Malta

- History of the Jews in Malta

- List of heads of state of Malta

- Malta Summit

- Norman-Arab-Byzantine culture

- Operation Pedestal

- Timeline of Maltese history

|