History of agriculture in Scotland facts for kids

The history of agriculture in Scotland covers all types of farming in Scotland, from ancient times to today.

Scotland has good land for growing crops and raising animals, mostly in the south and east. Heavy rain, strong winds, and salty sea spray, along with thin soil and too much grazing, made most western islands treeless. The hilly land also made travel difficult, so people often used coastal routes. Around 6,000 years ago, in the Neolithic period, people started living in permanent settlements and farming. They mainly grew grain and raised cows for milk. During the Bronze Age, more land was used for crops, and forests shrank. In the Iron Age, people built hill forts in southern Scotland, and the fertile plains were already heavily farmed. When the Romans were in Britain, trees grew back, suggesting less farming was happening.

The early Middle Ages saw a colder, wetter climate, making some land harder to farm. Farms were usually self-sufficient, meaning they grew all their own food. They were often just one home or a small group of homes. Oats and barley were common crops, and cows were the most important animals. From about 1150 to 1300, warmer, drier summers helped farming, allowing crops to grow in higher places and making land more productive. The system of "infield and outfield" farming might have started around the 12th century with feudalism. By the late Medieval period, most farming was done in "fermtouns" (Lowlands) or "bailes" (Highlands). These were small groups of families who farmed an area together using a system called run rig. Most ploughing was done with heavy wooden ploughs pulled by oxen. The farming economy grew in the 13th century. Even after the Black Death (a terrible disease) in 1349, it was still strong. But by the 1360s, incomes dropped sharply, slowly recovering in the 15th century.

In the early modern era, land ownership changed. Major landowners were called lairds and yeomen. Others with land rights included husbandmen and free tenants. Many young people became farm workers. This period also saw the "Little Ice Age", with colder, wetter weather, which meant Scotland had to import a lot of grain from other countries. Under the Commonwealth, Scotland was taxed heavily but could trade freely with England. After the Restoration, trade taxes with England returned. Generally, economic times were good, and landowners tried to improve farming and cattle raising. However, the late 1600s brought a slump and then the "seven ill years" of failed harvests. These were the last major food shortages of their kind. After the Union of 1707, people tried to improve farming even more. Enclosures replaced the run rig system and shared pastures. This led to the Lowland Clearances, where many farmers were forced to leave their homes. Later, the Highland Clearances saw many people in the Highlands displaced as land was used for sheep farming. Those who stayed became crofters, living on small rented farms, often relying on kelp (seaweed), fishing, linen spinning, and military service for extra income. Scotland's last big food crisis happened in 1846 when potato blight hit the Highlands.

In the 20th century, Scottish farming became more affected by world markets. Prices rose sharply during the First World War, then fell in the 1920s and 1930s, and rose again in the Second World War. In 1947, annual price reviews were started to help stabilize the market. After the Second World War, there was a big push for more food production, leading to intensive farming and more machines. The UK joined the European Economic Community in 1972, and farming became tied to its policies, with some parts of farming only surviving with help from subsidies. From the 1990s, changes to the Common Agricultural Policy tried to control over-production and reduce environmental damage. Now, there are large commercial farms and smaller, more varied farms that do other things like tourism.

Contents

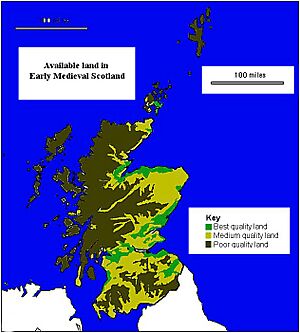

Scotland's Land and Weather

Scotland is about half the size of England and Wales, but it has a similar amount of coastline. Only about one-fifth to one-sixth of Scotland's land is good for farming or raising animals (land below 60 meters or 200 feet above sea level). Most of this good land is in the south and east. This meant that in the past, farming on less fertile land and fishing were very important for the economy. Scotland's location in the east Atlantic brings a lot of rain, about 700 centimeters (275 inches) per year in the east and over 1000 centimeters (390 inches) in the west. This rain helped peat bogs to spread. The acidic soil of these bogs, along with strong winds and salty sea spray, made most of the western islands treeless. Hills, mountains, quicksands, and marshes also made farming and travel difficult.

Farming in Ancient Scotland

Around 9600 BCE, after the ice from the last Ice Age melted, Scotland became a place where people could live again. The first known settlements were from Mesolithic hunter-gatherers. For example, an encampment near Biggar dates back to about 8500 BCE. Other sites show people who moved around a lot, used boats, and made tools from bone, stone, and antlers. The oldest known house in Britain, an oval wooden structure, was found near South Queensferry and dates to about 8240 BCE.

In the Neolithic period, starting around 6,000 years ago, there is clear evidence of permanent settlements and farming. This includes the well-preserved stone house at Knap of Howar on Papa Westray, from about 3500 BCE, and the village of similar houses at Skara Brae in Orkney, from about 500 years later. Evidence of early farming includes small plots of land with simple stone boundaries. On Shetland, these have been found under peat, and on the mainland, they are linked to cairnfields (piles of rocks cleared from fields). Evidence from pollen, pottery, settlements, and human remains shows that grain and cow milk were the two main food sources, a pattern that likely continued for a long time. There's also some evidence of flax being grown.

From the start of the Bronze Age, around 2000 BCE, studies show that land used for crops expanded, and forests became smaller. In the Iron Age, starting in the seventh century BCE, hill forts appeared. Some of these forts in southern Scotland are connected to cultivation ridges and terraces. Over 400 souterrains, which are small underground structures, have been found in Scotland, many in the south-east. These were likely used for storing perishable farm products. Old field systems seen from the air show that the fertile plains were already heavily farmed. During the time of Roman occupation in northern England and occasional trips into southern Scotland, trees like birch, oak, and hazel grew back for five centuries. This suggests that the Roman presence might have reduced farming activities.

Farming in the Middle Ages

The early Middle Ages brought a colder, wetter climate, making more land unproductive. Because there were no good transport links or big markets, most farms had to grow all their own food, including meat, dairy, and cereals. They also hunted and gathered food. Evidence suggests that farms in Northern Britain were either a single home or a small group of three or four homes. Oats and barley grew better than other grains in this climate. Bones show that cows were the most important farm animal, followed by pigs, sheep, and goats. Chickens were very rare.

From about 1150 to 1300, the warm, dry summers and milder winters of the Medieval Warm Period allowed farming to happen at higher elevations and made land more productive. Crop farming grew a lot, but it was still more common in low-lying areas than in the Highlands, Galloway, or the Southern Uplands. The feudalism system, introduced by David I, especially in the east and south, meant that land was held from the king or a lord in exchange for loyalty and military service. However, it's not clear how this new system affected the daily lives of ordinary farmers. The focus on raising animals in Scotland might have made it hard to set up a manorial system like in England. Farmers' duties often included occasional work, giving food, offering hospitality, and paying rent.

The "infield and outfield" farming system, a type of open field farming, might have come with feudalism and lasted until the 18th century. The infield was the best land, close to homes. It was farmed constantly and intensely, getting most of the animal manure. Crops usually included bere (a type of barley), oats, and sometimes wheat, rye, and legumes. The larger outfield was mostly used for oats. It was fertilized by cattle grazing overnight in the summer and often left empty to regain its richness. In fertile areas, the infield could be large, but in the uplands, it might be small with a lot of outfield. Near the coast, seaweed was used as fertilizer, and around towns, city waste was used. Crop yields were quite low, often producing only about three times the amount of seed planted.

By the late Medieval period, most farming was based in the Lowland fermtoun or Highland baile. These were small settlements of a few families who farmed an area together. They used a system called run rig, where land was divided into strips for tenant farmers, known as husbandmen. Below the husbandmen were cottars, who had small plots of land and worked as hired labor. Some people, called grassmen, only had rights to graze animals.

Run rigs were strips of furrow and ridge that usually ran downhill. This helped them include both wet and dry land, which was useful in extreme weather. Most ploughing was done with a heavy wooden plough with an iron coulter, pulled by oxen. Oxen were better for heavy soils and cheaper to feed than horses. Farmers often had to provide oxen to plough the lord's land and grind their grain at the lord's mill, which they disliked. Important crops included kale (for people and animals), and hemp and flax for making cloth. Sheep and goats were probably the main sources of milk, while cattle were raised mostly for meat. The rural economy seemed to boom in the 13th century. Even after the Black Death arrived in Scotland in 1349, killing perhaps over a third of the people, the economy was still strong. But by the 1360s, incomes dropped sharply, recovering slowly in the 15th century. Towards the end of this period, temperatures started to drop again, with cooler and wetter conditions limiting how much land could be farmed, especially in the Highlands.

Farming in the Early Modern Era

As the old feudal system changed, local landowners, called tenants-in-chief, became more important. By the 16th century, these often became the main landowners in an area. These tenants-in-chief and the barons eventually formed a new group called lairds, similar to English gentlemen. Below the lairds were various groups, including yeomen, who often owned a lot of land. A practice called "feuing" allowed people to pay a sum and an annual fee to own land and pass it to their heirs. This increased the number of people who owned land that used to belong to the church or nobility. By the 17th century, there were about 10,000 lairds and feuars, who became known as heritors. They took on more of the financial and legal duties of local government. Most of the working population were involved in farming just enough to feed themselves. This included husbandmen, smaller landowners, and free tenants. In the Lowlands, many young people, both male and female, left home to work as farm servants. Women were a very important part of the farm workforce. Unmarried women worked as farm servants, and married women worked with their husbands on all major farm tasks. They were especially important during harvest as part of the reaping team.

The early modern era also saw the "Little Ice Age", with colder and wetter weather, which was worst towards the end of the 17th century. Almost half the years in the late 1500s had food shortages, meaning large amounts of grain had to be shipped from the Baltic Sea region, which was called Scotland's "emergency granary." This grain came mainly from Poland, but later from other ports like Königsberg and Riga. Scottish communities were even set up in these ports. In the early 17th century, famine was common, with four periods of very high food prices between 1620 and 1625. The English invasions in the 1640s greatly affected Scotland's economy, destroying crops and disrupting markets, leading to very fast price increases. Under the Commonwealth, Scotland was taxed heavily but gained access to English markets. After the Restoration, trade taxes with England were brought back. Economic conditions were generally good from 1660 to 1688, as landowners encouraged better farming and cattle raising. By the end of the century, drovers roads, stretching from the Highlands to north-east England, were well-established routes for Highland cattle to reach English markets. The last decade of the 17th century saw the end of these good economic times. There was a slump in trade from 1689 to 1691, followed by four years of failed harvests (1695, 1696, 1698–99), known as the "seven ill years." This led to severe famine and a drop in population, especially in the north. These famines were particularly bad because food shortages had become rare in the second half of the 17th century. The shortages of the 1690s would be the last of their kind.

Farming Changes in the 18th Century

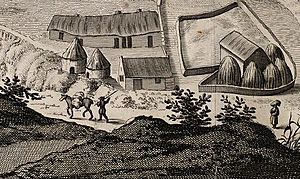

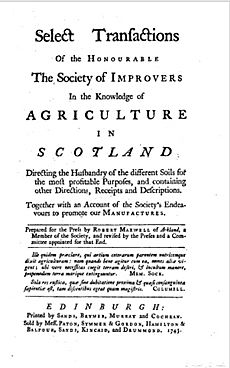

After the Union of 1707, Scotland had more contact with England. This led to a deliberate effort by wealthy landowners to improve farming. The Society of Improvers was founded in 1723, with 300 members including dukes, earls, and landlords. They introduced haymaking, the English plough, and new grasses like rye grass and clover. Turnips and cabbages were also brought in. Farmers used lime to reduce soil acidity, drained marshes, built roads, and planted trees. New techniques like drilling and sowing seeds, and crop rotation (changing crops in a field each year), were adopted. The introduction of the potato to Scotland in 1739 greatly improved what ordinary people ate. Enclosures began to replace the old run rig system and shared pastures, creating the rectangular fields we see in the Lowlands today. New farm buildings, often based on design books, replaced the old fermtouns. Smaller farms kept the longhouse style, with the house, barn, and animal shed in a row. But larger farms often had a three- or four-sided layout, separating the house from barns and servants' quarters.

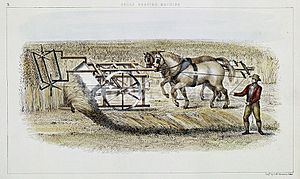

Early improvements used traditional tools, but new technology became more important. Lighter ploughs were adopted, including James Small's cast iron plough from 1763. This spread across the country in the 1770s. From 1788, Andrew Meikle's automated threshing mill sped up the important process of separating grain from stalks. Farming also became more specialized by region. The Lothians became a major grain-growing area, Ayrshire focused on cattle breeding, and the Borders on sheep.

These changes led to the Lowland Clearances. Hundreds of thousands of cottars and tenant farmers in central and southern Scotland were forced to leave the farms their families had lived on for hundreds of years. Many small settlements were taken apart. The people were forced to move to new villages built by landowners, or to industrial cities like Glasgow and Edinburgh, or even to northern England. Tens of thousands also moved to Canada or the United States, where they could own and farm their own land.

Farming in the 19th Century

Farming continued to improve in the 19th century. New inventions included the first working reaping machine, created by Patrick Bell in 1828. His rival, James Smith, focused on improving drainage under the soil. He developed a ploughing method that could break up the hard layer under the topsoil without disturbing the topsoil itself. This meant that low-lying, previously unworkable "carselands" could now be used for growing crops, creating the flat Lowland landscape we still see.

While the Lowlands saw many farming improvements, the Highlands remained very poor and traditional. A few powerful families, like the dukes of Argyll, Atholl, Buccleuch, and Sutherland, owned the best lands and controlled local politics, law, and economy. As late as 1878, 68 families owned nearly half the land in Scotland. Especially after the end of the boom caused by the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars (1790–1815), these landlords needed money to keep their high status in London society. They started demanding money rents and paid less attention to the traditional family-like relationship they had with the clans. This was made worse after the Corn Laws were removed in the mid-1800s, when Britain adopted free trade. This meant grain imported from America was cheaper, making it less profitable to grow crops in Scotland.

One result of these changes was the Highland Clearances. Many people in the Highlands were forced to leave their homes as land was enclosed, mainly to be used for sheep farming. The clearances followed wider patterns of agricultural change across the UK, but they were especially harsh because they happened late, there was little legal protection for tenants, the change from the traditional clan system was sudden, and many evictions were brutal. This led to a continuous movement of people away from the land—to cities, or further away to England, Canada, America, or Australia. Many who stayed became crofters, living on very small rented farms with no fixed end date, used to grow various crops and raise animals. For these families, collecting kelp (seaweed), fishing, spinning linen, and military service became important ways to earn extra money. Scotland faced its last major food crisis when the potato blight (the same disease that caused the Irish potato famine) reached the Highlands in 1846. About 150,000 people who relied mainly on potatoes faced disaster. They were saved by an effective emergency relief system, which was different from the failures in Ireland, but the risk of starvation continued into the 1850s.

The unequal ownership of land remained a sensitive issue and was strongly challenged in the 1880s by the Highland Land League. After the Napier Commission report in 1883, the government stepped in. They passed the Crofters' Holdings (Scotland) Act, 1886 to lower rents, guarantee that tenants could stay on their land, and break up large estates to provide crofts for homeless people. This law gave Scottish smallholders clear security, including the legal right to pass their tenancies to their children. A Crofting Commission was also created in 1886.

Farming from the 20th Century to Today

In the 20th century, Scottish farming became more affected by the ups and downs of world markets. Prices rose sharply during the First World War, but then fell in the 1920s and 1930s (when about 40 percent of Scottish land changed hands), followed by more price rises in the Second World War. In 1947, annual price reviews were introduced to help stabilize the market. Several laws followed, designed to support prices and give grants to farmers. After the Second World War and the related rationing, there was a big push in UK agriculture to produce more food. This lasted until the late 1970s, leading to more intensive farming. More areas of less fertile land were brought into use with government help. At the same time, the amount of forest tripled. Scottish agriculture became more mechanized. Horses were replaced by tractors and combine harvesters. This meant farming needed fewer workers. In 1951, 88,000 people worked full-time in Scottish agriculture, but by 1991, this number had fallen to about 25,000, leading to more people leaving rural areas. This helped make Scottish agriculture one of the most efficient in Europe.

In the 1960s and 1970s, 76–77 percent of the value of farm output came from raising animals. Although this has dropped to about 64 percent since 1990, crop farming is still a smaller part of the sector, and two-thirds of agricultural land is rough pasture. As a result, chemical use and crop-based subsidies have had less impact on Scottish biodiversity than in England, where farming is mostly about crops. The UK joining the European Economic Community (later the European Union) in 1972 changed the focus for Scottish farming. A preference for Commonwealth markets was replaced by EU rules. Agriculture became dominated by the EU's Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), which made farming rely on market support and direct grants to farmers. Because of this, some parts of farming, especially hill sheep farming, could only survive with subsidies. Eighty-four percent of Scottish land qualified for extra support as a Less Favoured Area (LFA), but 80 percent of the payments went to only 20 percent of the farmers, mainly large commercial crop farms in the Lowlands. A series of reforms to the CAP from the 1990s tried to control over-production, limit incentives for intensive farming, and reduce environmental damage. To help with the depopulation and commercialization of Scottish farming, the Crofting Act of 1976 made it easier for crofters to buy their farms. However, most crofts were too small to support a family, so many small farmers turned to fish farming and tourism to earn extra money. A dual farm structure has emerged, with agriculture divided between large commercial farms and small, varied holdings that do different things. Scotland has the highest average farm size in the European Union, almost ten times the average.

Images for kids