History of the Romanian language facts for kids

The history of the Romanian language began a long, long time ago in areas north of the Jireček Line during ancient Roman times. There are three main ideas about where exactly it started:

- Some think it grew only in Dacia, north of the Danube River.

- Others believe it developed only in Roman areas south of the Danube.

- A third idea suggests it grew on both sides of the Danube.

Between the 6th and 8th centuries AD, the everyday Latin spoken by people (called Vulgar Latin) slowly changed. It also picked up a few words from an older, unknown language. As the Roman Empire's power weakened, this language became what we call Common Romanian. This early form of Romanian then came into close contact with Slavic languages as Slavic people moved into the Balkans. After this, Common Romanian split into four main languages: Aromanian, Megleno-Romanian, Istro-Romanian, and Daco-Romanian (which is what we usually call Romanian today). Because there are not many written records from the 6th to the 16th centuries, experts have to guess how some parts of its history unfolded.

Contents

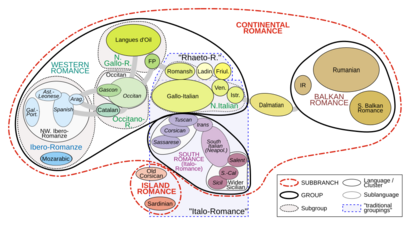

Eastern Romance Languages

Many centuries ago, several Romance languages were spoken in Southeastern Europe. However, one branch, the Dalmatian language, disappeared a long time ago. The remaining Eastern Romance languages, even though they have split into four main ones, share many features. This shows they all came from the same original language, Common Romanian.

Romanian is the biggest of these languages, spoken by over 20 million people, mostly in Romania and Moldova. Aromanian has about 350,000 speakers, mainly in the mountains of Albania, Greece, and Macedonia. A few thousand people near Thessaloniki speak Megleno-Romanian. The smallest Eastern Romance language is Istro-Romanian, with fewer than 1,500 speakers in Istria.

How Romanian Changed Over Time

Old Language Influences (Substratum)

Not much is known about the very old language that was spoken in the area before Latin arrived. This old language is called the "substratum." Most experts think it was an Indo-European language similar to Albanian. Some linguists call it "Thraco-Dacian," while others think it was Illyrian.

We only know a small number of words from these old languages. For example, about a hundred plant names and many town and personal names from Dacian have been found. Even fewer words are known from Thracian or Illyrian.

Experts believe that about 90 to 140 Romanian words come from this old substratum language. At least 70 of these words are similar to words in Albanian. This might mean the old language was closely related to Albanian, or even its ancestor. Some words might have been borrowed from Albanian into Romanian over time.

Many of these old words describe nature, like land, plants, and animals. About 30% of the words shared with Albanian are related to herding animals.

Romanian also shares some grammar and sentence structure features with Albanian, Bulgarian, and other languages in Southeastern Europe. This could be because of a common old language, but we don't know enough to be sure. It's also possible these similarities just developed on their own in each language.

Roman Rule and Everyday Latin

The Roman Empire started taking over parts of Southeastern Europe around 60 BC. The Dalmatian language, which was a mix between Romanian and Italian, began to develop in these coastal areas. The Romans continued to expand towards the Danube River in the 1st century AD. They created new provinces like Pannonia and Moesia, and Roman Dacia in 106 AD.

Roman soldiers and settlers helped the Romans control the local people. New Roman towns, called "colonies," also helped strengthen Roman rule. This led to a peaceful time, known as Pax Romana, which lasted until the end of the 2nd century. During this time, language, customs, and technology became more similar across the empire. However, some old local languages still survived until at least the late 4th century.

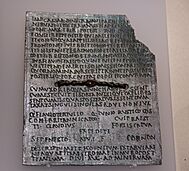

By the time the Romans conquered Southeastern Europe, the formal written Latin (Classical Latin) and the everyday spoken Latin (Vulgar Latin) were already becoming different. Roman settlers brought these popular forms of Latin to the new provinces. Inscriptions from the Roman period show that the Latin spoken in Southeastern Europe changed in the same ways as Latin in other parts of the empire until the late 3rd century. Many Romanian words we use today come from these everyday Latin forms. For example, some Latin vowels merged, and many Romanian words come from popular Latin terms, not formal ones.

The Roman province of Dacia, north of the Lower Danube, was left by the Romans in the early 270s. The people who left Dacia were moved south of the river, where a new province called Dacia Aureliana was created. However, some old writings say that Latin was still used north of the Lower Danube until the 6th century. For example, a report from 448 AD mentions that people under the Huns who traded with the Western Roman Empire spoke Latin.

Even though the Goths and other tribes often attacked Roman areas after the Romans left Dacia, Emperors Diocletian and Constantine the Great made the empire's borders stronger. The empire split into two parts in 395 AD, but Latin remained one of the two official languages of the Eastern Roman Empire until the early 7th century. Emperor Justinian I, who was born in Dardania, even said Latin was his native language. Roman rule in the Balkan Peninsula ended around 610 AD.

Old writings and inscriptions show that Latin was still the main language in the provinces along the Danube from the 4th to the 6th centuries. The last Latin inscriptions in the area are from the 610s. Some place names from that time even show vowel changes that are typical of Romanian's development. The first words that might be Romanian, "torna, torna fratre" ("turn, turn brother"), were shouted by a soldier in 587 AD.

Experts like Ovid Densusianu noted that everyday Latin "lost its unity" and split into the different Romance languages we have today. For example, a sound change that happened in Western Romance languages (like French or Spanish) didn't happen in Eastern Romance and Dalmatian languages. Romanian shares features with Italian, Romansh, and Dalmatian, suggesting they developed similarly for a while.

Early Romanian (Common Romanian)

The Romanian linguist Ovid Densusianu used the term "Thraco-Roman" in 1901 to describe the very first stage of the Romanian language. This was when everyday Latin, between the 4th and 6th centuries, changed into what is now called Proto-Romanian. About 20% of Romanian words come directly from Latin. A high percentage of Latin words are found in areas like senses (86.1%), quantity (82.3%), family (76.9%), and time (74.7%). More than 90% of small connecting words, 80% of adverbs, and 68% of adjectives in Romanian came directly from Latin.

Some Latin words related to city life survived but changed their meaning to fit a rural environment. For example, pământ (earth) comes from Latin pavimentum (pavement). Words for navigation, higher religious organization, and education became much less common. Romanian words for "road" also show that the ancestors of Romanians lived a more rural life after the Roman Empire declined. For instance, the Latin word for bridge, pons, became Romanian punte, which means a tree trunk over a ditch. The Romanian word for road, cale, came from Latin callis, meaning a narrow path.

Based on studies of Latin and borrowed words in Romanian, many experts believe that Romanians came from people who lived in the mountainous areas of Southeastern Europe and mainly raised animals. For example, the word for "to plow" comes from Latin, but the names for parts of the plow and plowing techniques were borrowed from Slavic. This suggests that their ancestors only knew the very basics of farming. However, other experts say that many words for crops and farming methods came directly from Latin, showing a long history of farming. They also point out that most fruit-growing, beekeeping, and pig-raising terms are Latin, suggesting a mixed farming society.

Like only a few other Romance languages, Romanian kept the name Romanus for itself. Its variant rumân, which meant serfs, was first written down in the 1500s. The variant român is found as early as the 17th century. However, other people called Romanians "Vlachs" throughout the Middle Ages. This name came from an old Germanic word that first referred to Celts, then to Romanized Celts, and finally to all Romance speakers. Slavs adopted it, and then Greeks.

Historians don't fully agree on the exact date when Romanians were first clearly mentioned in history. Some Romanian historians say there are records from the 8th and 9th centuries, but they don't name them. One historian mentions a 9th-century Armenian text that talks about an "unknown country called Balak," but others say this part was added much later. Some experts suggest the first recorded events involving Romanians are their fights against the Hungarians around 895 AD, north of the Danube. They refer to old chronicles, but their reliability is often questioned. However, it's clear that Vlachs in the Balkan Peninsula are mentioned in Byzantine sources from the late 10th century.

Slavic Influence

Large areas north of the Lower Danube were controlled by Goths and Gepids for at least 300 years after the 270s. However, no Romanian words from these East Germanic languages have been found. On the other hand, Slavic languages had a much stronger impact on Romanian than Germanic languages had on French, Italian, or Spanish. Even though many Slavic loanwords have been replaced by Latin-based words since the 19th century, about 15% of Romanian words are still of Slavic origin.

Slavic words are especially common in areas like house (26.5%), religion (25%), basic actions and technology (22.6%), social and political relations (22.5%), and agriculture (22.5%). About 20% of Romanian adverbs, nearly 17% of nouns, and around 14% of verbs come from Slavic. Slavic loanwords often exist alongside a similar word inherited from Latin, sometimes leading to slightly different meanings. For example, both "timp" (from Latin) and "vreme" (from Slavic) can mean time or weather, but "vreme" is now preferred for weather. Slavic loanwords often have an emotional meaning and are positive. Many linguists believe these features suggest that there were once communities where both Slavic and Romanian were spoken, with many Slavic speakers learning Romanian.

The earliest Slavic words, about 80 terms, were adopted during the Common Slavic period, which ended around 850 AD. However, most Slavic words in Romanian were adopted after a specific sound change in Common Slavic. Old Church Slavonic also added many religious words to Romanian during this time. Proto-Romanian even adopted some Latin or Greek words through Slavic languages. Romanian and Istro-Romanian separated from the southern dialects around the 10th century, but they kept many common Slavic words. After that, each Eastern Romance language borrowed words from its neighboring Slavic peoples. For example, Ukrainian and Russian influenced northern Romanian dialects, while Croatian influenced Istro-Romanian.

Besides words, Slavic languages also affected Romanian sounds and grammar, though experts debate how much. One debated feature is the appearance of a "y" sound before "e" at the beginning of some words. Some say it was because people switched from Common Slavic to Eastern Romance, while others say it was a natural change in Latin that happened in many Romance languages. The way numbers from eleven to nineteen are formed in Romanian clearly follows a Slavic pattern (e.g., unsprezece "one-on-ten"). This also suggests that many people who originally spoke Slavic later adopted Romanian.

Pre-Literary Romanian

The time between the 10th century, when the northern dialects of Common Romanian separated from the southern ones, and the first known writings in Romanian in the 16th century, is called the pre-literary stage of the language.

During this period, new sounds appeared, like the vowel [ɨ]. The final u sound often disappeared. The ea diphthong from Common Romanian became a single vowel (e.g., feată changed to fată). Old Church Slavonic continued to influence the language, and Hungarian words also entered the vocabulary.

The presence of Romanians in the Kingdom of Hungary is confirmed by sources from the early 13th century. The Pechenegs and the Cumans spoke Turkic languages. It's hard to tell which words came from them versus later borrowings from Crimean Tatar or Ottoman Turkish. For example, the Romanian word for mace (buzdugan) might come from the Cumans or Pechenegs. The word cioban (shepherd), which is also in Albanian and Slavic languages, could be of Pecheneg or Cuman origin.

Living alongside Hungarians led Romanians to adopt some Hungarian words. Today, about 1.6% of Romanian words are Hungarian. They are relatively common in areas like social and political relations, clothing, speech, and house. While most Hungarian words have spread across all Romanian dialects, many are only used in Transylvania.

Some Eastern Romance languages and dialects adopted many new words, while others remained more traditional. The Wallachian dialect of Romanian is the most innovative. Many linguists believe that the preservation of old Latin words in dialects spoken in Roman Dacia, which were replaced by borrowed words in other regions, shows that these areas were centers of "linguistic expansion." The Maramureș dialect has also kept Latin words that disappeared from most other dialects. On the other hand, Aromanian, even though it's now spoken in areas far from where it developed, still uses many inherited Latin terms instead of borrowed words found in other Eastern Romance languages.

Development of Written Romanian

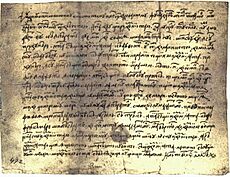

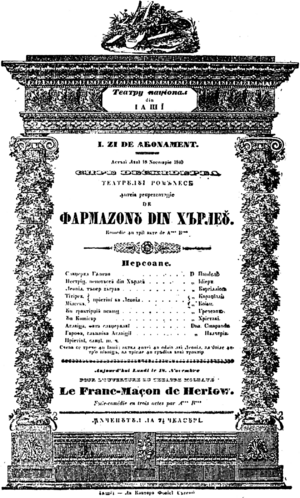

The oldest surviving Romanian writing that can be accurately dated is a letter sent by Lupu Neacșu from Câmpulung, Wallachia, to Johannes Benkner of Brașov, Transylvania. Based on the people and events mentioned, it was likely written around June 29 or 30, 1521. The Hurmuzaki Psalter, from the same period, is a copy of an older translation of the Psalms from the 15th century. The period from the early 16th century (when the first Romanian writings appeared) to 1780 (when the Transylvanian School's grammar Elementa linguae daco-romanae sive valachicae was published) defines the development of Literary Romanian. This time is also called Old Romanian.

In 1476, the Polish historian Jan Długosz noted that Moldavians and Wallachians "share a language and customs." During the 16th century, many foreign scholars and chroniclers observed that the people and language were called "Romanian."

In Moldavia

The first complete texts in Romanian appeared in Moldavia in the early 16th century. Four manuscripts, including the Hurmuzaki Psalter, are known as Rhotacizing Texts because they show a specific sound change where "n" between vowels became "r."

Moldavian chronicles first appeared as translations into Old Church Slavonic from a Byzantine chronicle. The first Romanian authors wrote in Old Church Slavonic too. But from the time of Grigore Ureche (around 1590-1647), the chronicle was written in Romanian, telling about Moldavian events from 1359 to 1594. Ureche, in his The Chronicles of the land of Moldavia (1640s), said the Moldavian language was a mix of many languages (Latin, French, Greek, Polish, Turkish, Serbian, etc.) and mixed with neighboring languages.

Miron Costin continued Ureche's chronicle, adding events from 1595 to 1661. Like Ureche, Costin was a nobleman and supported the prince's rule with the boyars' advice. He wrote about the brief unification of Wallachia, Transylvania, and Moldavia by Prince Michael the Brave. He strongly supported the idea that Romanians came from Romans, suggesting that Roman settlers in Dacia moved to the mountains during the Middle Ages and reappeared in the 14th century. In his De neamul moldovenilor (1687), he noted that Moldavians, Wallachians, and Romanians in Hungary had the same origin. He also said that while Moldavians called themselves "Moldavians," they called their language "Romanian" (românește).

Ion Neculce, a boyar from a Greek family, used a language closer to the everyday speech in northern Moldavia. He added events from 1661 to 1743.

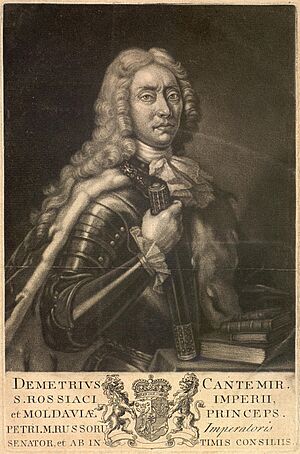

Dimitrie Cantemir (1673–1723), a prince of Moldavia and a very knowledgeable person, is considered one of the most important Romanian writers. He is best known for his book "Incrementa atque decrementa aulae othomanicae" ("History of the Growth and Decay of the Ottoman Empire"), written in Latin. This book was a main source of information on Ottoman history for a century. Cantemir was a pioneer in Romanian literature, writing the first allegory and biography in Romanian.

In his Descriptio Moldaviae (1714), he pointed out that people in Moldavia, Wallachia, and Transylvania spoke the same language. However, he noted some differences in accent and vocabulary. For example, he said:

- "Wallachians and Transylvanians have the same speech as the Moldavians, but their pronunciation is slightly harsher, such as giur, which a Wallachian will pronounce jur, using a Polish ż or a French j. [...] They also have words that the Moldavians don't understand, but they don't use them in writing."

Cantemir's work is one of the earliest histories of the language. Like Ureche, he noted its evolution from Latin and the words borrowed from Greek, Turkish, and Polish. He also suggested that some words might have come from Dacian roots. Cantemir also observed that while the idea of a Latin origin for the language was common then, some scholars thought it came from Italian.

In old sources, like the works of chroniclers Grigore Ureche and Miron Costin, or Prince Dimitrie Cantemir, the term Moldavian (moldovenească) can be found. According to Cantemir's Descriptio Moldaviae, people in Wallachia and Transylvania spoke the same language as Moldavians, but with different pronunciation and some unique words. Costin and Cantemir also confirmed that people in the Principality of Moldavia used the term Romanian to refer to their own language.

In Wallachia

Unlike Moldavia, where historical writing developed early and in a clear order, in Wallachia it was delayed and later split due to political disagreements. Older documents until the early 17th century were mostly short accounts of historical moments and figures, written mainly in Old Church Slavonic or sometimes Greek. Neacșu's letter is a notable exception.

Boyar Stoica Ludescu (around 1612-1695) might have been the first to write a Wallachian chronicle in Romanian. He gathered documents and earlier attempts at chronicles, adding his own history of the second half of the 17th century in Wallachia. His work was followed by Constantin Cantacuzino (1639-1716), who studied at the University of Padua. He helped publish the first complete Bible in Romanian and wrote History of Wallachia (1716). This book covered events from the Roman colonization until the conquest by Attila the Hun. Cantacuzino had a different view from the Moldavian chroniclers. He claimed that modern Romanians came directly from Roman aristocrats who he believed mixed with the Dacians, forming a Daco-Roman people.

During the rule of Constantin Brâncoveanu, his courtier Radu Greceanu wrote the prince's biography. He praised the prince's good deeds and showed his right to rule by connecting his family to Byzantine Emperors and earlier Wallachian ruling families. Greceanu's work was challenged by another anonymous chronicler who argued for an elected monarchy.

Towards the end of the Old Romanian period and the start of Modern Romanian, during the Enlightenment, Wallachian literature in Romanian became more diverse. The Văcărescu family produced many poets and writers. The first of them to be recognized, Ienăchiță Văcărescu, also published a grammar study called "Observațiuni sau băgări dă seamă asupra regulelor și orânduelelor gramaticii românești."

In Transylvania and Banat

Like in Wallachia, the history of Romanian writing in Transylvania, Banat, and other regions where Romanians lived in the Kingdom of Hungary was slow at first. It was marked by unconnected writings before a more unified approach to Romanian language, culture, and politics emerged in the 19th century.

Early Romanian scholars used the official languages of the Kingdom. However, Romanians generally had few representatives in politics and high culture. A notable exception was Nicolaus Olahus, Archbishop of Esztergom (1553-1568) and a friend of Erasmus. In his Latin description of his country, Hungaria, he wrote that the Romanian language in Wallachia, Moldavia, and Transylvania originally came from the classical Latin of Roman settlers in Dacia.

The first books in Romanian appeared as the Reformation and the printing press spread in the region. Deacon Coresi, born in Wallachia but mostly active in Brașov, brought his printing knowledge. Among his prints were books in Romanian. The Palia de la Orăștie is the oldest translation of the first five books of the Bible written in Romanian. It was printed in 1582 in Orăștie, then a center of the Reformation in Transylvania. It was written using the Romanian Cyrillic alphabet.

In the early 17th century, the first chronicle in Transylvania was written by Protopop Vasile, an Orthodox clergyman from Brașov. He wrote a historical sketch of St. Nicolai's church at Șchei in Brașov and listed local events from 1392 to 1633. His work was continued in the 18th century by Radu Tempea, who described the Romanian Orthodox-Catholic church union of 1697-1701, among other events.

In Banat, the first Romanian chronicle was written only in the early 19th century by the Orthodox priest Nicolae Stoica. He told the history of the region from the beginning of the world until 1825, focusing on the Austro-Turkish War (1788–1791), which he witnessed.

The most important movement that shaped Romanian writing in the Kingdom of Hungary is known as the Transylvanian School. Its main members were Samuil Micu-Klein, Petru Maior, and Gheorghe Șincai. This "School," whose members were connected to the Romanian public school in Blaj (established in 1754), promoted ideas of ethnic purity, Latin origin, and the continuous presence of Romanians in Dacia. They also published many religious and educational writings. Important for the language's history was their interest in Romanian language studies. Books like Maior's Orthographia Romana and shorter studies on word origins, spelling, and grammar were collected in 1825 as the Buda Lexicon. Of the many books published by the Transylvanian School, Samuil Micu-Klein's and Gheorghe Șincai's Elementa linguae daco-romanae sive valachicae (published in Vienna in 1780) was the most influential. In it, the authors promoted using a Latin-based alphabet and studied Romanian grammar scientifically.

Modern Romanian

The period starting from 1780, with the publication of Elementa linguae daco-romanae sive valachicae, is called Modern Romanian. This time is marked by the translation and printing of books using both Cyrillic and Latin writing. This continued until the current Romanian alphabet was fully adopted in 1881. It's also characterized by the strong influence of other Romance languages, especially French, on Romanian words. This influence, along with the adoption of the Latin alphabet, led to discussions about "Re-Latinization" or "Westernization" of Romanian. For example, French loanwords like objection became objecție, and Latin-inherited words sometimes gained new, similar words from French (like dens from French vs. des inherited from Latin, both from Latin densus).

The early period involved unorganized efforts to simplify the unclear Cyrillic spellings of Romanian. This slow process led to new letters being introduced (like ț and ș). Between 1828 and 1859, transitional alphabets were used. There was also a debate among academics about whether to base spelling on Latin origins or on how words sounded. The introduction of the Latin-based alphabet (at different times in Wallachia and Transylvania – 1860, and Moldova – 1862) and the first official spelling rules in 1881, which were mostly based on how words sounded and on Wallachian pronunciation, removed regional differences.

Romanian in Imperial Russia

After Russia took over Bessarabia in 1812, the language of Moldavians was made an official language in government offices there, used alongside Russian. This was because most of the people were Romanian. Publishing houses set up by Archbishop Gavril Bănulescu-Bodoni printed books and religious works in Moldavian between 1815 and 1820.

Slowly, the Russian language became more important. A new law in 1829 ended Bessarabia's self-rule and stopped the mandatory use of Moldavian in public announcements. In 1854, Russian was declared the only official language of the region, and Moldavian was removed from schools later that century.

According to Bessarabia's records, official documents were published only in Russian starting in 1828. Around 1835, a 7-year period was set during which government offices would accept documents in Romanian. After that, only Russian would be used.

Romanian was allowed as the language of teaching until 1842, after which it was taught as a separate subject. For example, at the seminary in Chișinău, Romanian was a required subject with 10 hours a week until 1863, when the Romanian Department was closed. At High School No.1 in Chișinău, students could choose between Romanian, German, and Greek until February 9, 1866. On that date, the State Counselor of the Russian Empire banned the teaching of Romanian, saying: "the pupils know this language in the practical mode, and its teaching follows other goals."

Around 1871, the tsar issued an order "On the suspension of teaching the Romanian language in the schools of Bessarabia," because "local speech is not taught in the Russian Empire." Bessarabia became a regular province, and the policy of making everyone speak Russian became a priority.

The language situation in Bessarabia from 1812 to 1918 saw a gradual increase in bilingualism (speaking two languages). Russian became the official language of power, while Romanian remained the main everyday language. This change happened in five stages.

From 1812 to 1828, there was a neutral period where both languages were used. Russian was dominant officially, but Romanian was still important in public administration, education (especially religious), and culture. In the years right after the annexation, loyalty to the Romanian language and customs was strong. The Chișinău Theological Seminary and Lancaster Schools opened, Romanian grammar books were published, and a printing press in Chișinău started producing religious books.

From 1828 to 1843, there was a partial diglossic bilingualism. During this time, Romanian was forbidden in administration. This was done by removing Romanian from the laws. Romanian continued to be used in education, but only as a separate subject. Bilingual books, like the Russian-Romanian grammar Bucoavne, were published to help with the new need for bilingualism. Religious books and Sunday sermons were the only public places where only Romanian was used. By 1843, Romanian was completely removed from public administration.

From 1843 to 1871, it was a period of assimilation. Romanian continued to be a school subject at the high school until 1866, at the Theological Seminary until 1867, and at regional schools until 1871, when all teaching of the language was forbidden by law.

From 1871 to 1905, there was official monolingualism in Russian. All public use of Romanian was gradually stopped and replaced with Russian. Romanian continued to be used as the everyday language at home and with family. This was when the most assimilation happened in the Russian Empire. In 1872, a priest ordered all church documents to be in Russian, and in 1882, the printing press in Chișinău was closed.

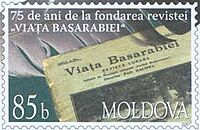

From 1905 to 1917, there was growing language conflict as Romanian national awareness re-emerged. In 1905 and 1906, local councils in Bessarabia asked for Romanian to be brought back into schools as a "required language" and for "freedom to teach in the mother language (Romanian language)." At the same time, the first Romanian language newspapers and journals began to appear, such as Basarabia (1906) and Viața Basarabiei (1907). From 1913, the church allowed "churches in Bessarabia to use the Romanian language."

The term "Moldovan language" (limbă moldovenească) was newly used to create a state-supported language that was different from 'Romanian' Romanian. For example, in 1827, Ștefan Margeală stated that his book aimed to help the 800,000 Romanians in Bessarabia and millions in other parts of the Prut River learn Russian, and also for Russians to learn Romanian. In 1865, Ioan Doncev, editing his Romanian primer, said that Moldovan was valaho-româno, or Romanian. However, after this date, the label "Romanian language" appeared only rarely in educational records. Gradually, Moldovan became the only label for the language. This was useful for those who wanted to separate Bessarabia culturally from Romania.

How Romanian Sounds Changed

This section looks at the sound changes that happened as Latin turned into Romanian. The order of these changes is not necessarily the exact order they happened in.

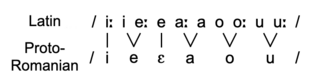

Changes Up to Proto-Romanian

During the Everyday Latin Period

Vowels

Classical Latin had ten pure vowels and three diphthongs (two vowel sounds in one syllable). By the 1st century AD, some Latin diphthongs changed into single vowel sounds. For example, ae became like a long "e," and oe also became like a long "e." The diphthong au generally stayed the same in most areas for centuries, and it still exists in Romanian today.

Long and short Latin vowels like e, i, o, u were different in both their sound quality and how long they were held. The shorter versions were lower and more relaxed. Long and short a only differed in how long they were held. At some point, the length of the vowel stopped being important. All vowels became long in stressed open syllables (syllables ending in a vowel) and short everywhere else. This made long and short a merge.

Romanian and other Eastern Romance languages followed a mixed pattern for vowels. The back vowels (like o, u) merged their long and short forms, losing the quality difference. But the front vowels (like e, i) kept their quality difference. This resulted in a six-vowel system in Romanian.

For example, short and long back vowels merged:

- Latin mare > Romanian mare ('sea')

- Latin focum > Romanian foc ('fire')

Latin short u sometimes changed to o when stressed and before m or b:

- Latin autumna > Romanian toamnă ('autumn')

Latin long ō changed to u in a few words:

- Latin cohortem > Romanian curte

Front vowels changed like this:

- Latin ē and i became e.

- Latin ī became i.

- Latin e and ae became ɛ in stressed syllables and e in unstressed syllables.

- Later, stressed ɛ became the diphthong ie.

For example:

- Latin pellem > Romanian piele ('skin')

- Latin vīnum > Romanian vin ('wine')

Romanian tended to keep syllables from Latin in most cases (e.g., piersică from persĭca). It also kept consonants between vowels, like deget from digitus.

Breaking of stressed e

In Romanian, a stressed e sound often broke into the diphthong ie. This happened in all syllables.

- Latin pellem > Romanian piele ('skin')

Often, the "y" sound in ie was later absorbed by the consonant before it.

- Latin decem > di̯ece > dzece > Romanian zece ('ten')

The e sound was later affected by other changes, sometimes breaking into ea or changing to a:

- Latin equa > i̯epa > Romanian iapă ('mare')

- Latin terra > ti̯era > țeară > Romanian țară ('land')

Breaking of e and o

The vowel o broke into oa when followed by a non-high vowel:

- Latin flōrem > Romanian floare ('flower')

The vowel e broke into ea in similar situations. The e was often absorbed by a preceding palatal sound:

- Latin equa > i̯epa > i̯eapa > Romanian iapă ('mare')

As a result, these diphthongs still switch with the original single vowels. They appear regularly before a, ă, and e in the next syllable. However, ea changed back to e before another e (e.g., mese 'tables' from mēnsae).

Backing of e

The vowel e changed to ă (a sound like "uh" in "duh"). The diphthong ea was reduced to a when it was after a lip sound (like p, b, m) and before a back vowel (like a, o, u) in the next syllable. It stayed e when the next vowel was i or e. Also, before i or e, the diphthong ea changed back to e.

- Latin pilus > Romanian păr ('hair'), but

- Latin pilī > Romanian peri ('hairs')

- Latin mēnsam > measă > Romanian masă ('table'), but

- Latin mēnsae > mease > Romanian mese ('tables')

The consonant r also causes e to change to ă: Latin rēus > Romanian rău ('bad'). Another source of ă is when a changes to ă before i in the next syllable (e.g., mare 'sea', but mări 'seas').

Vowel reduction

Unstressed a became ă (except at the beginning of a word), and unstressed o became u. Then ă became e after palatal consonants (sounds made with the middle of the tongue against the roof of the mouth). Unstressed o was kept in some words due to analogy (similarity to other words).

- Latin capra > Romanian capră ('goat')

- Latin formōsus > Romanian frumos ('beautiful')

New vowels ă and ɨ

As the definite article -a (like "the" in English) appeared, it created new word forms with unstressed -a: casă ('house') vs. casa ('the house'). Also, stressed a sometimes became ă before n or a consonant cluster starting with m. Later, ă (from both original a and from e) developed into the vowel ɨ (spelled as î or â). For example, Latin campus > Romanian câmp ('field'). This was part of a general change where vowels changed before nasal sounds. Latin i also sometimes became ɨ before nasal sounds: Latin sinus > sân ('breast'). Later, when n was deleted in some words, ɨ became a distinct sound: Latin quantum > Romanian cât ('how much').

The same vowel ɨ also comes from i, e, and ă before a cluster of r and another consonant: Latin virtutem > Romanian vârtute ('virtue'). The vowel also comes from i after r: Latin ridet > Romanian râde ('laughs'). More ɨ sounds appeared with the introduction of Slavic and later Turkish words.

Consonants

Labiovelars

In everyday Latin, sounds like qu and gu (pronounced with lips and back of tongue) became simple k and g before front vowels. These were later changed to ch and j sounds by a process called palatalization.

- Latin quaerere "to seek" > Romanian cere 'ask'

- Latin sanguis "blood" > Romanian sânge

The labiovelars originally stayed before a, but later changed to p and b. However, in question words starting with qu-, this change to p- never happened.

- Latin quattuor > Romanian patru 'four'

- Latin equa > Romanian iapă 'mare'

- Latin lingua > Romanian limbă 'tongue'

- But Latin quandō > Romanian când 'when'

Labialization of velars

Another important change is that velar sounds (made with the back of the tongue) became labial sounds (made with the lips) before dental sounds (made with the tongue against the teeth). This includes changes like ct to pt, gn to mn, and x to ps. Later, ps became ss, then s or ș in most words.

- Latin factum > Romanian fapt 'fact; deed'

- Latin signum > Romanian semn 'sign'

- Latin coxa > Romanian coapsă 'thigh'

Final consonants

In both Romanian and Italian, almost all consonants at the end of words were lost. Because of this, for a time, all words in Romanian ended with vowels. Also, after a long vowel, a final -s created a new final -i:

- Latin nōs > Romanian noi 'we'

- Latin trēs > Romanian trei 'three'

Palatalization

In everyday Latin, short e and i followed by another vowel changed into a glide sound (like "y"). Later, this "y" sound changed the consonants before it, especially those made with the front of the tongue or the back of the tongue.

- For tj and kj sounds, the results in Romanian were different:

- If followed by a, o, or u at the end of a word, they became a "ts" sound.

- Latin puteus > Romanian puț 'well, pit'

- If followed by o or u not at the end of a word, they became a "ch" sound.

- Latin rōgātiōnem > Romanian rugăciune 'prayer'

- If followed by a, o, or u at the end of a word, they became a "ts" sound.

- Other consonants:

- Latin hordeum > Romanian orz 'barley'

- Latin cāseus > Romanian caș 'fresh cheese'

- Latin mulierem > Romanian muiere 'woman'

These palatalizations happened in all Romance languages, though with slightly different results. However, lip sounds (like p, b, m) were not affected by these changes. Instead, later, the "y" sound moved to a different place in the word:

- Latin rubeum > Romanian roib

Palatalization of cl and gl clusters

The Latin cl sound cluster changed to kly, which later simplified to k. The same happened to Latin gl:

- Latin oricla > Romanian ureche 'ear'

- Latin glacia > Romanian gheață 'ice'

l-rhotacism

At some point, the Latin l sound between vowels changed into r. This happened after the palatalization mentioned above, but before double consonants simplified and before i-palatalization. Some examples:

- Latin gelu > Romanian ger 'frost'

- Latin salīre > Romanian a sări ('to jump')

Second palatalization

The dental consonants (t, d, s, l) were palatalized again by a following i or y sound (from the combination ie/ia which came from stressed e):

- Latin testa > ti̯esta > țesta > Romanian țeastă 'skull'

- Latin decem > di̯ece > dzece > Romanian zece 'ten'

- Latin servum > si̯erbu > Romanian șerb 'serf'

- Latin sex > si̯asse > Romanian șase 'six'

- Latin leporem > li̯epure > Romanian iepure 'hare'

- Latin dīcō > dziku > Romanian zic 'I say'

- Latin līnum > Romanian in 'flax'

- Latin gallīna > Romanian găină 'hen'

The velar consonants (k, g) from Latin qu and gu changed to ch and j sounds before front vowels:

- Latin quid > Romanian ce 'what'

- Latin quīnque > Romanian cinci "five"

- Latin quaerere "to seek" > Romanian cere 'ask'

- Latin sanguem > Romanian sânge 'blood'

Modern Changes

These are changes that did not happen in all Eastern Romance languages. Some happen in standard Romanian; some do not.

Spirantization

In southern dialects and in the standard language, the dz sound changed to z everywhere:

- dzic > zic ('I say')

The dʒ sound (like "j" in "jump") became j (like "s" in "measure") only when it was "hard" (meaning followed by a back vowel):

- gioc > joc ('game'), but:

- deget ('finger') did not change.

Weakening of resonant sounds

Old palatal resonant sounds (like ly and ny) became weaker, changing to y, which was later lost next to i:

- Latin leporem > Romanian iepure 'hare'

- Latin līnum > Romanian in 'flax'

- Latin gallīna > Romanian găină 'hen'

- Latin vīnea > Romanian vie 'vineyard'

The l sound between vowels from Latin double ll was completely lost before a, first changing to a w sound:

- Latin stēlla > Romanian stea 'star'

- Latin sella > Romanian șa 'saddle'

The l sound from Latin double ll was kept before other vowels:

- Latin caballum > Romanian cal 'horse'

The v sound between vowels (from Latin b or v) was lost, perhaps first weakening to a w sound:

- Latin būbalus > Romanian bour 'aurochs'

n-epenthesis

More recently, a stressed u preceded by n became longer and nasalized, producing an extra n sound.

- Latin genuculus > Romanian genunchi 'knee'

- Latin minutus > Romanian mărunt 'minute, small'

j-epenthesis

In some words, the semivowel j (like "y") was inserted between â and a soft n:

- pâne > pâine ('bread')

- câne > câine ('dog')

This also explains the plural mână - mâini ('hand, hands'). This change is common in southern dialects and the standard language. It might have spread from the Oltenian dialect to literary Romanian.

Hardening

The backing of vowels after ș, ț, and dz is specific to northern dialects. Because these consonants can only be followed by back vowels, any front vowel changes to a back one:

- și > șî 'and'

- ține > țâni̯e 'holds'

- zic > dzâc 'I say'

This is similar to how vowels change after "hard" consonants in Russian.

See also

- Albanian–Eastern Romance linguistic parallels

- Legacy of the Roman Empire

- Old Romanian

| Victor J. Glover |

| Yvonne Cagle |

| Jeanette Epps |

| Bernard A. Harris Jr. |