History of the Ottoman Empire facts for kids

The Ottoman Empire was a powerful state founded around 1299 by a leader named Osman I. It started as a small area in what is now northwestern Turkey, close to the Byzantine capital, Constantinople. In 1326, the Ottomans captured the city of Bursa, which helped them gain more control over the region. They first crossed into Europe in 1352, setting up a permanent base at Çimpe Castle in 1354. Their capital then moved to Edirne in 1369. During this time, many smaller Turkish states in Asia Minor joined the growing Ottoman Empire, either by being conquered or by choosing to become part of it.

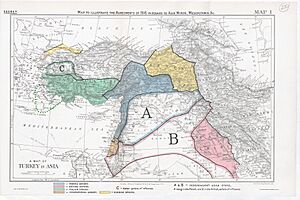

When Sultan Mehmed II conquered Constantinople (now called Istanbul) in 1453, it became the new Ottoman capital. The empire grew much larger, spreading into Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East. By the mid-1500s, most of the Balkans were under Ottoman rule. Sultan Selim I greatly expanded the empire in 1517, conquering western Arabia, Egypt, Mesopotamia, and the Levant. Soon after, much of the North African coast (except Morocco) also became part of the Ottoman lands.

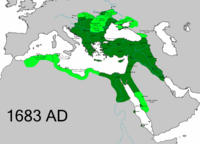

The empire was at its strongest under Suleiman the Magnificent in the 16th century. It stretched from the Persian Gulf in the east to Algeria in the west, and from Yemen in the south to Hungary and parts of Ukraine in the north. This time was known as the "classical period," when Ottoman culture, arts, and political power were at their peak. The empire reached its largest size in 1683, just before the Battle of Vienna.

After 1699, the Ottoman Empire began to lose land over the next two centuries. This happened because of problems within the empire, expensive wars, European countries taking over lands, and people wanting their own independent nations. By the early 1800s, leaders knew they needed to modernize. They tried many reforms to stop the decline, with different levels of success. The weakening of the Ottoman Empire led to what was called the "Eastern Question" in the mid-1800s, as European powers wondered what would happen to its territories.

The empire finally ended after its defeat in World War I. Its remaining lands were divided by the Allied powers. The sultan's rule was officially ended by the Turkish Grand National Assembly on November 1, 1922, after the Turkish War of Independence. For over 600 years, the Ottoman Empire left a lasting mark on the Middle East and Southeast Europe, influencing the customs, culture, and food of many countries that were once part of it.

Contents

How the Ottoman Empire Grew (1299–1453)

After the Seljuk Sultanate of Rum ended in the 12th and 13th centuries, Anatolia was split into many independent states called Anatolian Beyliks. These states were under the control of the Mongolians for some time. By 1300, the Byzantine Empire was weak and had lost most of its lands in Anatolia to these Turkish groups. One of these groups was led by Osman I (who died around 1323/4), and the name Ottoman comes from him. He was the son of Ertuğrul and lived near Eskişehir in western Anatolia.

A famous story, "Osman's Dream," says that Osman was inspired to conquer lands by a vision. In his dream, his empire was a huge tree with roots spreading across three continents and branches reaching the sky. This tree had four rivers flowing from its roots: the Tigris, the Euphrates, the Nile, and the Danube. It also shaded four mountain ranges: the Caucasus, the Taurus, the Atlas, and the Balkan ranges. During his time as Sultan, Osman I expanded Turkish settlements towards the edge of the Byzantine Empire.

During this early period, the Ottoman government began to take shape. Its rules and ways of working would change a lot over the empire's long history.

In the century after Osman I's death, Ottoman rule started to spread across the Eastern Mediterranean and the Balkans. Osman's son, Orhan, captured the city of Bursa in 1326 and made it the new capital. The fall of Bursa meant the Byzantines lost control of northwestern Anatolia.

After securing their lands in Asia Minor, the Ottomans crossed into Europe starting in 1352. Within ten years, they had conquered almost all of Thrace, cutting off Constantinople from its lands in the Balkans. The Ottoman capital moved to Edirne in 1369. The important city of Thessaloniki was taken from the Venetians in 1387. The Ottoman victory at Kosovo in 1389 effectively ended Serbian power in the region, allowing the Ottomans to expand further into Europe. The Battle of Nicopolis in 1396, often seen as the last major crusade of the Middle Ages, failed to stop the Ottoman advance.

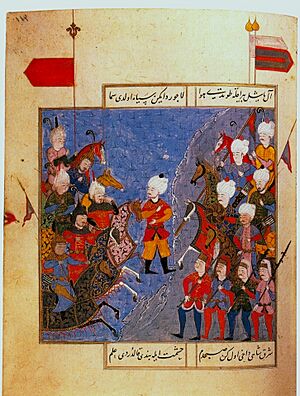

With Turkish rule spreading into the Balkans, conquering Constantinople became a key goal. The Empire controlled almost all the former Byzantine lands around the city. However, the Byzantines got a temporary break when Timur invaded Anatolia in the Battle of Ankara in 1402. He captured Sultan Bayezid I. Bayezid I's capture caused chaos among the Turks. The state fell into a civil war from 1402 to 1413, as Bayezid's sons fought for control. It ended when Mehmed I became sultan and brought back Ottoman power, ending this period of confusion.

-

Sultan Mehmed I. Ottoman miniature, 1413-1421

Some Ottoman lands in the Balkans (like Thessaloniki, Macedonia, and Kosovo) were lost after 1402. But they were later won back by Murad II between the 1430s and 1450s. On November 10, 1444, Murad II defeated the armies of Hungary, Poland, and Wallachia at the Battle of Varna. This was the final battle of the Crusade of Varna. Four years later, János Hunyadi prepared another army, but Murad II defeated him again at the Second Battle of Kosovo in 1448.

Murad II's son, Mehmed the Conqueror, reorganized the government and the army. He showed his military skill by capturing Constantinople on May 29, 1453, when he was only 21 years old.

The Golden Age (1453–1566)

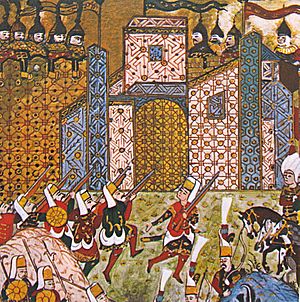

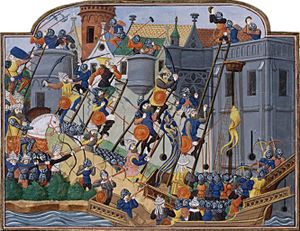

The Ottoman capture of Constantinople in 1453 by Mehmed II made the Empire the most powerful state in southeastern Europe and the eastern Mediterranean. After taking Constantinople, Mehmed met with the Orthodox religious leader, Gennadios. They agreed that the Eastern Orthodox Church could keep its independence and lands if it accepted Ottoman rule. Many Orthodox people preferred Ottoman rule over Venetian rule, especially because of the bad relationship between the late Byzantine Empire and Western European states.

When Istanbul became the new capital in 1453, Mehmed II took the title Kayser-i Rûm, meaning "Roman Emperor." To support this claim, he planned to conquer Rome, the former western capital of the Roman Empire. He spent years securing positions on the Adriatic Sea, like in Albania Veneta. Then, on July 28, 1480, he launched an Ottoman invasion of Otranto in Italy. The Turks stayed in Otranto for almost a year. But after Mehmed II died on May 3, 1481, plans to go deeper into Italy were canceled, and the remaining Ottoman troops sailed back east.

During the 15th and 16th centuries, the Ottoman Empire had a long period of conquest and expansion. Its borders stretched deep into Europe and North Africa. Land conquests were successful because of the Ottoman military's discipline and new ideas. At sea, the Ottoman Navy greatly helped this expansion. The navy also fought for and protected important sea trade routes. They competed with Italian city-states in the Black, Aegean, and Mediterranean seas, and with the Portuguese in the Red Sea and Indian Ocean.

The empire also became very rich because it controlled the main land trade routes between Europe and Asia.

The Empire thrived under a series of strong and dedicated Sultans. Sultan Selim I (1512–1520) greatly expanded the empire's eastern and southern borders. He defeated Shah Ismail I of Safavid Persia in 1514 at the Battle of Chaldiran. Selim I established Ottoman rule in Egypt and created a naval presence on the Red Sea. After this expansion, the Portuguese Empire and the Ottoman Empire competed to be the main power in the region. This conquest ended with the execution of Tuman bay II.

Selim's son, Suleiman the Magnificent (1520–1566), continued his father's conquests. After capturing Belgrade in 1521, Suleiman conquered the southern and central parts of the Kingdom of Hungary. The western, northern, and northeastern parts of Hungary remained independent.

After his victory in the Battle of Mohács in 1526, he established Turkish rule in much of present-day Hungary and other Central European areas. He then tried to capture Vienna in 1529, but failed because winter forced his army to retreat.

In 1532, he made another attack on Vienna. But he was stopped at the Siege of Güns, about 97 kilometers (60 miles) south of the city. In another version of the story, the city's commander, Nikola Jurišić, was offered terms for a peaceful surrender. However, Suleiman withdrew when the August rains arrived and did not continue towards Vienna as planned.

After more Turkish advances in 1543, the Habsburg ruler Ferdinand officially recognized Ottoman power in Hungary in 1547. During Suleiman's reign, Transylvania, Wallachia, and sometimes Moldavia, became states that paid tribute to the Ottoman Empire. In the east, the Ottoman Turks took Baghdad from the Persians in 1535. This gave them control of Mesopotamia and access to the Persian Gulf by sea. By the end of Suleiman's reign, the empire had about 15 million people.

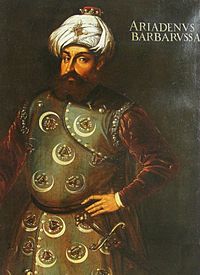

Under Selim and Suleiman the Magnificent, the Empire became a leading naval power, controlling much of the Mediterranean Sea. The actions of the Ottoman admiral Barbarossa Hayreddin Pasha, who led the Ottoman Navy during Suleiman's reign, resulted in many military victories over Christian navies. Important naval victories for the Ottoman Empire during this time included the Battle of Preveza (1538), Battle of Ponza (1552), and Battle of Djerba (1560). They also conquered Algiers (in 1516 and 1529) and Tunis (in 1534 and 1574) from Spain. They took Rhodes (1522) and Tripoli (1551) from the Knights of St. John. They captured Nice (1543) from the Holy Roman Empire, Corsica (1553) from the Republic of Genoa, and the Balearic Islands (1558) from Spain. They also captured Aden (1548), Muscat (1552), and Aceh (1565–67) from Portugal during their Indian Ocean expeditions.

The conquests of Nice (1543) and Corsica (1553) were joint efforts between the French king Francis I and the Ottoman sultan Suleiman I. They were led by the Ottoman admirals Barbarossa Hayreddin Pasha and Turgut Reis. A month before the siege of Nice, France supported the Ottomans with artillery during the Ottoman conquest of Esztergom in 1543. France and the Ottoman Empire became strong allies during this time, united by their shared opposition to Habsburg rule in Europe. This alliance was both economic and military. The sultans allowed France to trade within the Empire without paying taxes. By this time, the Ottoman Empire was an important and accepted part of European politics. It formed military alliances with France, the Kingdom of England, and the Dutch Republic against Habsburg Spain, Italy, and Habsburg Austria.

Suleiman I's plan to expand across the Mediterranean was stopped in Malta in 1565. During a long summer siege, known as the Siege of Malta, about 50,000 Ottoman soldiers fought against the Knights of St. John and the Maltese defenders, who numbered 6,000. The strong resistance by the Maltese led to the siege being lifted in September. This unsuccessful siege was the second and last defeat for Suleiman the Magnificent, after the equally unsuccessful first Ottoman siege of Vienna in 1529. Suleiman I died of natural causes in his tent during the Siege of Szigetvár in 1566. The Battle of Lepanto in 1571 was another major setback for Ottoman naval power in the Mediterranean. This battle happened after the Ottoman capture of Venetian-controlled Cyprus in 1570. Despite the defeat, a new Ottoman fleet was built quickly, and Tunisia was recovered from Spain in 1574.

As the 16th century continued, Ottoman naval strength was challenged by the growing sea powers of Western Europe, especially Portugal. This happened in the Persian Gulf, Indian Ocean, and the Spice Islands. With the Ottoman Turks blocking sea routes to the East and South, European powers looked for new ways to reach the old silk and spice routes, which were now under Ottoman control. On land, the Empire was busy with military campaigns in Austria and Persia, two very distant war zones. The stress of these conflicts on the empire's resources, and the difficulty of keeping supply lines open over such vast distances, eventually made its sea efforts difficult to maintain. The main military need for defense on the western and eastern borders of the Empire made it impossible to fight effectively on a global scale for a long time.

Changes in the Ottoman Empire (1566–1700)

European countries began trying to reduce Ottoman control over the traditional land trade routes between East Asia and Western Europe, which started with the Silk Road. Western European states began to avoid the Ottoman trade monopoly by finding their own sea routes to Asia through new discoveries at sea. The Portuguese discovery of the Cape of Good Hope in 1488 led to a series of Ottoman-Portuguese naval wars in the Indian Ocean throughout the 16th century. Economically, the Price Revolution caused a lot of inflation in both Europe and the Middle East. This had serious negative effects on all parts of Ottoman society.

The expansion of Muscovite Russia under Ivan IV (1533–1584) into the Volga and Caspian regions, at the expense of the Tatar khanates, disrupted the northern pilgrimage and trade routes. A very ambitious plan to counter this, thought up by Sokollu Mehmed Pasha, the Grand Vizier under Selim II, was to build a Don-Volga canal (started June 1569). This, combined with an attack on Astrakhan, failed, and the canal was abandoned when winter began. After this, the Empire went back to its old strategy of using the Crimean Khanate as a defense against Russia. In 1571, the Crimean khan Devlet I Giray, supported by the Ottomans, burned Moscow. The next year, the invasion was repeated but was stopped at the Battle of Molodi. The Crimean Khanate continued to invade Eastern Europe with slave raids. It remained an important power in Eastern Europe and a threat to Muscovite Russia until the end of the 17th century.

In southern Europe, a group of Catholic powers, led by Philip II of Spain, formed an alliance to challenge Ottoman naval strength in the Mediterranean. Their victory over the Ottoman fleet at the Battle of Lepanto (1571) was a shocking blow to the idea that the Ottomans could not be defeated. However, historians today emphasize the symbolic importance of the battle, not just its military impact. Within six months of the defeat, a new Ottoman fleet of about 250 ships, including eight modern galleasses, had been built. The shipyards in Istanbul were building a new ship every day at the peak of construction. In talks with a Venetian minister, the Ottoman Grand Vizier said: "In capturing Cyprus from you, we have cut off one of your arms; in defeating our fleet you have merely shaved off our beard." The Ottoman navy's quick recovery convinced Venice to sign a peace treaty in 1573. The Ottomans were then able to expand and strengthen their position in North Africa. However, what could not be replaced were the experienced naval officers and sailors. The Battle of Lepanto hurt the Ottoman navy more by losing skilled people than by losing ships, which were quickly replaced.

In contrast, the border with the Habsburg Empire became quite stable. Only small battles happened over individual fortresses. This stalemate was due to stronger Habsburg defenses and simple geography: before modern machines, Vienna was the furthest an Ottoman army could march from Istanbul during the spring to autumn fighting season. It also showed the difficulties the Empire faced by having to fight on two separate fronts: one against the Austrians (see: Ottoman wars in Europe), and the other against a rival Islamic state, the Safavids of Persia (see: Ottoman wars in Near East).

Changes in European military tactics and weapons, part of the military revolution, made the Sipahi cavalry less important. The Long War against Austria (1593–1606) created a need for more infantry soldiers with firearms. This led to easier recruitment rules and a big increase in the number of Janissary soldiers. Irregular sharpshooters (Sekban) were also recruited for the same reasons. When they were no longer needed, they became bandits in the Jelali revolts (1595–1610). This caused widespread chaos in Anatolia in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. With the empire's population reaching 30 million people by 1600, a shortage of land put more pressure on the government.

However, the 17th century was not just a time of decline. It was a key period when the Ottoman state and its systems began to adapt to new pressures and situations, both inside and outside the empire. The Sultanate of women (1534–1683) was a time when the political influence of the Imperial Harem was very strong. The mothers of young sultans held power for their sons. This wasn't entirely new; Hürrem Sultan, who became powerful in the early 1530s, was described as "a woman of the utmost goodness, courage and wisdom." But the weakness of Ibrahim I (1640–1648) and the young age of Mehmed IV when he became sultan in 1646 created a big crisis in leadership. The powerful women of the Imperial Harem stepped in to fill this gap. The most important women of this period were Kösem Sultan and her daughter-in-law Turhan Hatice, whose political rivalry ended with Kösem's murder in 1651.

This period led to the very important Köprülü Era (1656–1703). During this time, a series of Grand Viziers from the Köprülü family effectively controlled the Empire. On September 15, 1656, the elderly Köprülü Mehmed Pasha accepted his position after getting promises from the Valide Turhan Hatice for unusual authority and freedom from interference. He was a strict conservative who successfully brought back central authority and the empire's military drive. This continued under his son and successor Köprülü Fazıl Ahmed (Grand Vizier 1661–1676). The Köprülü Viziers saw new military successes. Authority was restored in Transylvania, the conquest of Crete was completed in 1669, and the empire expanded into Polish southern Ukraine. The strongholds of Khotyn and Kamianets-Podilskyi and the territory of Podolia became Ottoman in 1676.

This period of renewed strength ended badly when Grand Vizier Kara Mustafa Pasha led a huge army to try a second Ottoman siege of Vienna in May 1683. This was part of the Great Turkish War of 1683–1699. The final attack was delayed too long, and the Ottoman forces were defeated by allied Habsburg, German, and Polish forces led by the Polish king Jan at the Battle of Vienna.

The alliance of the Holy League pressed their advantage after the defeat at Vienna. Fifteen years of back-and-forth warfare ended with the important Treaty of Karlowitz (January 26, 1699). This treaty ended the Great Turkish War. For the first time, the Ottoman Empire gave up control of significant European territories, many permanently, including Ottoman Hungary. The Empire could no longer effectively carry out an aggressive, expansionist policy against its European rivals. From this point on, it was forced to adopt a defensive strategy in Europe.

Only two Sultans in this period personally held strong political and military control of the Empire. The energetic Murad IV (1612–1640) recaptured Yerevan (1635) and Baghdad (1639) from the Safavids. He also brought back central authority, though his time as ruler was short. Mustafa II (1695–1703) led the Ottoman counterattack of 1695–96 against the Habsburgs in Hungary, but he was badly defeated at Zenta (September 11, 1697).

Decline and Modernization (1700–1827)

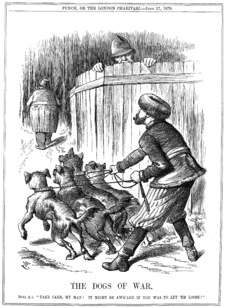

During this time, the Ottoman Empire faced threats from its old enemy, the Austrian Empire, and a new rising enemy, the Russian Empire. Some areas of the Empire, like Egypt and Algeria, became independent in all but name. Later, they came under the influence of Britain and France. In the 18th century, central authority within the Ottoman Empire weakened, and local governors and leaders gained more independence.

However, Russian expansion was a big and growing threat. Because of this, King Charles XII of Sweden was welcomed as an ally in the Ottoman Empire after his defeat by the Russians at the Battle of Poltava in 1709. Charles XII convinced the Ottoman Sultan Ahmed III to declare war on Russia. This led to the Ottoman victory at the Pruth River Campaign of 1710–1711. After the Austro-Turkish War (1716–1718), the Treaty of Passarowitz was signed on July 21, 1718. This brought a period of peace between wars. However, the Treaty also showed that the Ottoman Empire was on the defensive and unlikely to attack Europe further.

During the Tulip Era (1718–1730), named for Sultan Ahmed III's love of the tulip flower, the Empire's policy towards Europe changed. The Empire began to improve the defenses of its cities in the Balkan peninsula to protect against European expansion. Cultural works, fine arts, and architecture flourished, with more detailed styles influenced by the Baroque and Rococo movements in Europe. A good example is the Fountain of Ahmed III in front of the Topkapı Palace. The famous Flemish-French painter Jean-Baptiste van Mour visited the Ottoman Empire during the Tulip Era. He created some of the most famous artworks showing scenes from daily life in Ottoman society and the imperial court.

After Peter the Great died in 1725, his wife Catherine became Czarina Catherine I of the Russian Empire. Together with Austria, Russia, under Empress Anne, Catherine I's niece, fought a war against the Ottoman Empire from 1735 to 1739. The Treaty of Belgrade, signed on September 18, 1739, ended this war. It resulted in the Ottomans getting Belgrade and other territories back from Austria, but losing the port of Azov to the Russians. However, after the Treaty of Belgrade, the Ottoman Empire enjoyed a generation of peace. Austria and Russia had to deal with the rise of the Prussians under King Frederick the Great.

This long period of Ottoman peace and stagnation is often described by historians as a time of failed reforms. In the later part of this period, there were educational and technological reforms. This included setting up higher education institutions like the Istanbul Technical University. Ottoman science and technology had been highly respected in medieval times. This was because Ottoman scholars combined classical learning with Islamic philosophy and mathematics, and knew about Chinese advances like gunpowder and the magnetic compass. By this period, however, the influences had become less progressive and more traditional. In 1734, when an artillery school was set up with French teachers to teach Western-style artillery methods, Islamic religious leaders objected. They argued against it for religious reasons. The artillery school was not reopened on a semi-secret basis until 1754. Earlier, groups of writers had called the printing press "the Devil's Invention." This caused a 53-year delay between its invention by Johannes Gutenberg in Europe around 1440 and its introduction to Ottoman society. The first Gutenberg press in Istanbul was set up by Sephardic Jews from Spain in 1493, who had moved to the Ottoman Empire a year earlier to escape the Spanish Inquisition of 1492. However, the printing press was only used by non-Muslims in the Ottoman Empire until the 18th century. In 1726, Ibrahim Muteferrika convinced the Grand Vizier Nevşehirli Damat İbrahim Pasha, the Grand Mufti, and the clergy about how useful the printing press was. He later asked Sultan Ahmed III for permission to publish non-religious books. The Sultan granted permission, despite opposition from some calligraphers and religious leaders. Muteferrika's press published its first book in 1729. By 1743, it had published 17 works in 23 volumes, each with 500 to 1,000 copies.

Other small reforms were also made. Taxes were lowered, and there were attempts to improve the image of the Ottoman state. The first examples of private investment and business also appeared.

After a period of peace that lasted since 1739, Russia began to show its desire to expand again in 1768. Russian troops entered Balta, an Ottoman-controlled city on the border of Bessarabia, under the excuse of chasing Polish revolutionaries. They killed its citizens and burned the town. This action provoked the Ottoman Empire into the First Russo-Turkish War of 1768–1774. The Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca of 1774 ended this war. It allowed Christian citizens in the Ottoman-controlled Romanian provinces of Wallachia and Moldavia to worship freely. Russia was made the protector of their right to Christian worship.

A series of wars were fought between the Russian and Ottoman empires from the 18th to the 19th century. By the late 18th century, several defeats in wars with Russia led some people in the Ottoman Empire to believe that Peter the Great's reforms had given the Russians an advantage. They realized the Ottomans would need to keep up with Western technology to avoid more defeats.

Ottoman military reform efforts began with Selim III (1789–1807). He made the first major attempts to modernize the army like European armies. However, these efforts were stopped by groups who opposed change. These groups included some religious leaders, but mainly the Janissary corps, who had become unruly and ineffective. They were protective of their special rights and strongly against change. They caused a Janissary revolt. Selim's efforts cost him his throne and his life. But his successor, the energetic Mahmud II, solved this problem in a dramatic and bloody way by eliminating the Janissary corps in 1826.

The Serbian revolution (1804–1815) marked the start of a time of national awakening in the Balkans during the Eastern Question. Serbia's independence as a hereditary monarchy under its own dynasty was officially recognized in 1830. In 1821, the Greeks declared war on the Sultan. A rebellion that started in Moldavia as a distraction was followed by the main revolution in the Peloponnese. This area, along with the northern part of the Gulf of Corinth, became the first parts of the Ottoman Empire to gain independence (in 1829). By the mid-19th century, the Ottoman Empire was called the "sick man" by Europeans. The states that were under Ottoman rule but had their own rulers – the Principality of Serbia, Wallachia, Moldavia, and Montenegro – moved towards full independence during the 1860s and 1870s.

Decline and Modernization (1828–1908)

During this period, the empire struggled to defend itself against foreign invasion and occupation. The empire stopped fighting conflicts alone and began to form alliances with European countries like France, the Netherlands, Britain, and Russia. For example, in the 1853 Crimean War, the Ottomans teamed up with Britain, France, and the Kingdom of Sardinia against Russia.

Modernizing the Empire

During the Tanzimat period (1839–76), which means "organization" in Arabic, the government made a series of constitutional reforms. These led to a fairly modern army based on conscription, reforms in the banking system, making homosexuality no longer a crime, replacing religious law with secular law, and replacing guilds with modern factories. In 1856, the Hatt-ı Hümayun promised equality for all Ottoman citizens, no matter their background or religion. This expanded on the 1839 Hatt-ı Şerif of Gülhane.

Overall, the Tanzimat reforms had big effects. People educated in the schools set up during this period included Mustafa Kemal Atatürk and other progressive leaders and thinkers of the Republic of Turkey and many other former Ottoman states. These reforms included promises to keep Ottoman citizens' lives, honor, and property safe. They introduced the first Ottoman paper banknotes (1840) and opened the first post offices (1840). The finance system was reorganized like the French model (1840), and the Civil and Criminal Code was also reorganized based on the French model (1840). The Meclis-i Maarif-i Umumiye (1841) was established, which was the first version of the First Ottoman Parliament (1876). The army was reorganized with a regular way of recruiting soldiers and setting military service length (1843–44). An Ottoman national anthem and Ottoman national flag were adopted (1844). The first nationwide Ottoman census was done in 1844 (only male citizens were counted). The first national identity cards were introduced (1844). A Council of Public Instruction (1845) and the Ministry of Education (1847) were established. Slavery and the slave trade were abolished (1847). The first modern universities (1848), academies (1848), and teacher schools (1848) were set up. The Ministry of Healthcare (1850) and the Commerce and Trade Code (1850) were established. The Academy of Sciences (1851) and the Şirket-i Hayriye, which ran the first steam-powered commuter ferries (1851), were also created. The first European-style courts (1853) and supreme judiciary council (1853) were set up. The modern Municipality of Istanbul (1854) and the City Planning Council (1855) were established. The capitation (Jizya) tax on non-Muslims was abolished, and a regular way of collecting taxes was introduced (1856). Non-Muslims were allowed to become soldiers (1856). Various rules were made for better public service and trade. The first telegraph networks (1847–1855) and railways (1856) were built. Guilds were replaced with factories. The Ottoman Central Bank (1856) and the Ottoman Stock Exchange (1866) were established. The Land Code (1857) was introduced. Private sector publishers and printing firms were allowed (1857). The School of Economical and Political Sciences (1859) and the Press and Journalism Regulation Code (1864) were also established.

The Ottoman Ministry of Post was created in Istanbul on October 23, 1840. The first post office was near the Yeni Mosque. In 1876, the first international mailing network between Istanbul and lands outside the Ottoman Empire was set up. In 1901, the first money transfers were made through post offices, and the first cargo services began.

Samuel Morse received his first patent for the telegraph in 1847 at the old Beylerbeyi Palace in Istanbul. Sultan Abdülmecid personally tested the new invention. After this successful test, work began on the first telegraph line (Istanbul–Adrianople–Şumnu) on August 9, 1847. In 1855, the Ottoman telegraph network started working, and the Telegraph Administration was established. In 1871, the Ministry of Post and the Telegraph Administration merged, becoming the Ministry of Post and Telegraph. In July 1881, the first telephone circuit in Istanbul was set up. On May 23, 1909, the first manual telephone exchange with 50 lines opened in the Büyük Postane.

The reform period reached its peak with the Constitution, called the Kanûn-u Esâsî (meaning "Basic Law" in Ottoman Turkish). It was written by members of the Young Ottomans and announced on November 23, 1876. It established freedom of belief and equality for all citizens before the law. The empire's First Constitutional era was short-lived. But the idea of Ottomanism was important. A group of reformers called the Young Ottomans, who were mostly educated in Western universities, believed that a constitutional monarchy would solve the empire's growing social problems. Through a military coup in 1876, they forced Sultan Abdülaziz (1861–1876) to step down. His nephew, Murad V, took his place. However, Murad V was mentally ill and was removed from power within a few months. His successor, Abdülhamid II (1876–1909), was asked to become sultan on the condition that he would declare a constitutional monarchy, which he did on November 23, 1876. The parliament lasted only two years before the sultan closed it. When forced to reopen it, he abolished the representative body instead. This ended the effectiveness of the Kanûn-ı Esâsî.

The Christian millets (religious communities) gained special rights, like in the Armenian National Constitution of 1863. This set of rules had 150 articles written by Armenian thinkers. Another new group was the Armenian National Assembly. The Christian population of the empire, because of their better education, started to do better than the Muslim majority. This caused a lot of anger among Muslims. In 1861, there were 571 primary and 94 secondary schools for Ottoman Christians with 140,000 students. This number was much higher than the number of Muslim children in school at the same time. Muslim children were also held back by the time they spent learning Arabic and Islamic theology. In turn, the higher education levels of Christians allowed them to play a big role in the economy. In 1911, out of 654 wholesale companies in Istanbul, 528 were owned by ethnic Greeks.

New Railways

New railways were built during this period, including the first ones in the Ottoman Empire.

| Railway | Year established | Cities serviced |

|---|---|---|

| Cairo–Alexandria line | 1856 | Cairo–Alexandria |

| İzmir–Selçuk–Aydın line | 1856 | İzmir–Selçuk–Aydın |

| Köstence–Boğazköy railway line | 1860 | Köstence–Boğazköy |

| Smyrne Cassaba & Prolongements | 1863 | İzmir, Afyon, Bandırma |

| Rusçuk–Varna railway line | 1866 | Rusçuk, Varna |

| Bükreş–Yergöğü railway line | 1869 | Bükreş, Yergöğü |

| Chemins de fer Orientaux | 1869 | Vienna, Banja Luka, Saraybosna, Niš, Sofia, Filibe, Adrianople and Istanbul (starting from 1889 between Paris and Istanbul as the Orient Express) |

| Chemin de Fer Moudania Brousse | 1871 | Mudanya, Bursa |

| Istanbul-Belovo railway line | 1873 | Istanbul, Belovo |

| Üsküp–Selânik railway line | 1873 | Üsküp, Selânik |

| Mersin-Tarsus-Adana Railway | 1882 | Mersin, Tarsus, Adana |

| Chemins de Fer Ottomans d'Anatolie | 1888 | Istanbul, İzmit, Adapazarı, Bilecik, Eskişehir, Ankara, Kütahya, Konya |

| Jaffa–Jerusalem railway | 1892 | Jaffa, Jerusalem |

| Beirut-Damascus railway | 1895 | Beirut, Damascus |

| Baghdad Railway | 1904 | Istanbul, Konya, Adana, Aleppo, Baghdad |

| Jezreel Valley railway | 1905 | Acre, Haifa, Bosra, Hauran, Yagur, Daraa, Samakh, Beit She'an, Silat ad-Dhahr |

| Hejaz Railway | 1908 | Istanbul, Konya, Adana, Aleppo, Damascus, Amman, Tabuk and Medina |

| Eastern Railway | 1915 | Tulkarm, Lod |

| Beersheba Railway | 1915 | Nahal Sorek, Beit Hanoun, Beersheba. |

The Crimean War

The Crimean War (1853–1856) was part of a long struggle between major European powers. They all wanted influence over the lands of the declining Ottoman Empire. Britain and France successfully defended the Ottoman Empire against Russia.

Most of the fighting happened when the allies landed on Russia's Crimean Peninsula to gain control of the Black Sea. There were smaller battles in western Anatolia, the Caucasus, the Baltic Sea, the Pacific Ocean, and the White Sea. It was one of the first "modern" wars. It introduced new technologies like the first tactical use of railways and the telegraph. The Treaty of Paris (1856) that followed secured Ottoman control over the Balkan Peninsula and the Black Sea region. This lasted until their defeat in the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878).

The Ottoman Empire took its first foreign loans on August 4, 1854, shortly after the Crimean War began.

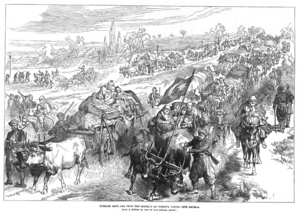

The war caused many Crimean Tatars to leave their homes. Out of 300,000 Tatars in the Tauride Province, about 200,000 moved to the Ottoman Empire in waves. Towards the end of the Caucasian Wars, 90% of the Circassians were forced to leave their homelands in the Caucasus and settled in the Ottoman Empire. Since the 19th century, many Muslim people from the Balkans, Caucasus, Crimea, and Crete moved to what is now Turkey. These people were called Muhacir. By the time the Ottoman Empire ended in 1922, half of Turkey's city population came from Muslim refugees from Russia. Crimean Tatar refugees in the late 19th century played a special role in trying to modernize Turkish education.

Rise of Nationalism

The rise of nationalism spread through many countries in the 19th century. It also affected lands within the Ottoman Empire. A growing sense of national identity and ethnic nationalism became one of the most important Western ideas to reach the Ottoman Empire. It had to deal with nationalism both inside and outside its borders. The number of revolutionary political parties grew a lot. Uprisings in Ottoman territory had many big consequences in the 19th century and shaped much of Ottoman policy in the early 20th century. Many Ottoman Turks wondered if the state's policies were to blame. Some felt that the causes of ethnic conflict came from outside and were not related to how the government was run. While this time had some successes, the Ottoman state's ability to stop ethnic uprisings was seriously questioned.

In 1804, the Serbian Revolution against Ottoman rule broke out in the Balkans. This happened at the same time as the Napoleonic invasion. By 1817, when the revolution ended, Serbia became a self-governing monarchy under nominal Ottoman rule. In 1821, the First Hellenic Republic became the first Balkan country to gain its independence from the Ottoman Empire. It was officially recognized by the Porte in 1829, after the Greek War of Independence ended.

Changes in the Balkans

The Tanzimat reforms did not stop the rise of nationalism in the Danubian Principalities and the Principality of Serbia, which had been semi-independent for almost sixty years. In 1875, the states that paid tribute to the empire, Serbia and Montenegro, and the United Principalities of Wallachia and Moldavia, declared their independence from the empire on their own. After the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878, the empire granted independence to all three warring nations. Bulgaria also gained independence (as the Principality of Bulgaria). Its volunteers had fought in the Russo-Turkish War alongside the rebelling nations.

The Congress of Berlin

The Congress of Berlin (June 13 – July 13, 1878) was a meeting of the main leaders of Europe's Great Powers and the Ottoman Empire. It happened after the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878), which ended with a clear victory for Russia and its Orthodox Christian allies in the Balkan Peninsula. The urgent need was to stabilize and reorganize the Balkans and create new nations. German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck, who led the Congress, worked to adjust borders to reduce the risk of a major war. He also recognized the reduced power of the Ottomans and tried to balance the different interests of the great powers.

As a result, Ottoman lands in Europe greatly decreased. Bulgaria was set up as an independent principality within the Ottoman Empire, but it was not allowed to keep all its previous territory. Bulgaria lost Eastern Rumelia, which was given back to the Turks under a special administration. Macedonia was returned completely to the Turks, who promised reforms. Romania gained full independence, but had to give part of Bessarabia to Russia. Serbia and Montenegro finally gained complete independence, but with smaller territories.

In 1878, Austria-Hungary took over the Ottoman provinces of Bosnia-Herzegovina and Novi Pazar on its own. However, the Ottoman government disagreed and kept its troops in both provinces. This situation lasted for 30 years. Austrian and Ottoman forces existed together in Bosnia and Novi Pazar for three decades. This ended in 1908 when the Austrians took advantage of the political problems in the Ottoman Empire caused by the Young Turk Revolution. They annexed Bosnia-Herzegovina but pulled their troops out of Novi Pazar to reach a compromise and avoid a war with the Turks.

In return for British Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli's support for returning Ottoman lands in the Balkan Peninsula during the Congress of Berlin, Britain took control of Cyprus in 1878. Later, in 1882, Britain sent troops to Egypt under the excuse of helping the Ottoman government stop the Urabi Revolt. This effectively gave Britain control in both territories. Britain officially took over the still nominally Ottoman territories of Cyprus and Egypt on November 5, 1914, because the Ottoman Empire decided to join World War I on the side of the Central Powers. France, for its part, occupied Tunisia in 1881.

The results were first praised as a great success in making peace and stability. However, most participants were not fully happy, and complaints about the results grew until they led to world war in 1914. Serbia, Bulgaria, and Greece gained some land, but much less than they thought they deserved. The Ottoman Empire, called the "sick man of Europe" at the time, was humiliated and greatly weakened. This made it more likely to have internal problems and more vulnerable to attack. Although Russia had won the war that led to the conference, it felt humiliated at Berlin and resented how it was treated. Austria gained a lot of territory, which angered the South Slavs and led to decades of tension in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Bismarck became hated by Russian nationalists and Pan-Slavists. He found that he had tied Germany too closely to Austria in the Balkans.

In the long run, tensions between Russia and Austria-Hungary grew. The question of different nationalities in the Balkans also became more intense. The Congress succeeded in keeping Istanbul in Ottoman hands. It effectively ignored Russia's victory. The Congress of Berlin returned territories to the Ottoman Empire that the previous treaty had given to the Principality of Bulgaria, especially Macedonia. This created a strong desire in Bulgaria to get these lands back. This led to the First Balkan War in 1912, where the Turks were defeated and lost almost all of Europe. As the Ottoman Empire slowly shrank in size, military power, and wealth, many Balkan Muslims moved to the empire's remaining territory in the Balkans or to the heartland in Anatolia. Muslims had been the majority in some parts of the Ottoman Empire, such as Crimea, the Balkans, and the Caucasus, as well as a large group in southern Russia and some parts of Romania. Most of these lands were lost by the Ottoman Empire between the 19th and 20th centuries. By 1923, only Anatolia and eastern Thrace remained Muslim land.

Egypt's Story

After gaining some independence in the early 1800s, Egypt entered a period of political trouble by the 1880s. In April 1882, British and French warships arrived in Alexandria. They came to support the khedive (ruler) and prevent the country from falling into the hands of anti-European groups. In August 1882, British forces invaded and occupied Egypt, saying they were bringing order. The British supported Khedive Tewfiq and brought back stability, which especially helped British and French financial interests. Egypt and Sudan remained Ottoman provinces officially until 1914. That's when the Ottoman Empire joined the Central Powers in World War I. Great Britain officially took over these two provinces and Cyprus in response. Other Ottoman provinces in North Africa were lost between 1830 and 1912. These included Algeria (occupied by France in 1830), Tunisia (occupied by France in 1881), and Libya (occupied by Italy in 1912).

Armenian People

Even though they were given their own constitution and national assembly with the Tanzimat reforms, the Armenians tried to demand that Article 61 from the Congress of Berlin in 1878 be put into action by the Ottoman government. After pressure from European powers and Armenians, Sultan Abdul Hamid II responded by assigning the Hamidiye regiments to eastern Anatolia (Ottoman Armenia). These were mostly irregular cavalry units made up of recruited Kurds. From 1894 to 1896, between 100,000 and 300,000 Armenians living throughout the empire were killed in what became known as the Hamidian massacres. Armenian activists took over the Ottoman Bank headquarters in Istanbul in 1896 to draw European attention to the events, but they did not get any help.

Defeat and End of the Empire (1908–1922)

The Ottoman Empire had long been called the "sick man of Europe." After a series of Balkan wars by 1914, it had been pushed out of almost all of Europe and North Africa. It still controlled 28 million people. Of these, 17 million were in modern-day Turkey, 3 million in Syria, Lebanon, and Palestine, and 2.5 million in Iraq. Another 5.5 million people were under nominal Ottoman rule in the Arabian peninsula.

The Second Constitutional Era began after the Young Turk Revolution (July 3, 1908). The sultan announced that the 1876 constitution was back in effect, and the Ottoman Parliament reconvened. This marked the beginning of the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire. This era was dominated by the politics of the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), and the movement known as the Young Turks. Although it started as a unifying progressive party, the CUP split in 1911. The opposition Freedom and Accord Party was founded, and it attracted many of the more liberal members from the CUP. The remaining CUP members, who now took on a more nationalist tone because of the hostility during the Balkan Wars, fought with Freedom and Accord in a series of power changes. This eventually led to the CUP (specifically its leaders, the "Three Pashas") taking power from Freedom and Accord in the 1913 Ottoman coup d'état. They established complete control over Ottoman politics until the end of World War I.

Taking advantage of the internal conflict, Austria-Hungary officially took over Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1908. But it pulled its troops out of the Sanjak of Novi Pazar, another disputed area between the Austrians and Ottomans, to avoid a war. During the Italo-Turkish War (1911–12), in which the Ottoman Empire lost Libya, the Balkan League declared war against the Ottoman Empire. The Empire lost the Balkan Wars (1912–13). It lost its Balkan territories except East Thrace and the historic Ottoman capital city of Adrianople during the war. About 400,000 Muslims, fearing violence from Greeks, Serbians, or Bulgarians, left with the retreating Ottoman army. The Baghdad Railway under German control was a plan to build rail lines into Iraq. The railway was not actually built at this time, but its possibility worried the British until that issue was resolved in 1914. The railway did not play a role in starting World War I.

World War I (1914–1918)

The Young Turk government had signed a secret treaty with Germany and formed the Ottoman-German Alliance in August 1914. This alliance was against their common enemy, Russia, and it aligned the Empire with Germany. The Ottoman Empire entered World War I after the Goeben and Breslau incident. In this event, it gave safe harbor to two German ships fleeing British ships. These ships, after officially being transferred to the Ottoman Navy but still under German control, attacked the Russian port of Sevastopol. This pulled the Empire into the war on the side of the Central Powers, where it took part in the Middle Eastern theatre. There were several important Ottoman victories in the early years of the war, such as the Battle of Gallipoli and the Siege of Kut. But there were also setbacks, like the disastrous Caucasus Campaign against the Russians. The United States never declared war against the Ottoman Empire.

In 1915, as the Russian Caucasus Army continued to advance in eastern Anatolia with the help of Armenian volunteer units from the Caucasus region of the Russian Empire, and aided by some Ottoman Armenians, the Ottoman government decided to issue the Tehcir Law. This law started the deportation of ethnic Armenians, especially from provinces near the Ottoman-Russian front. This led to what became known as the Armenian genocide. Through forced marches and conflicts, Armenians living in eastern Anatolia were moved from their homes and sent south to the Ottoman provinces in Syria and Mesopotamia. Estimates vary on how many Armenians died, with figures ranging from 300,000 to 1.5 million.

The Arab Revolt which began in 1916 turned the tide against the Ottomans on the Middle Eastern front. They initially seemed to be winning during the first two years of the war. When the Armistice of Mudros was signed on October 30, 1918, the only parts of the Arabian peninsula still under Ottoman control were Yemen, Asir, the city of Medina, and parts of northern Syria and Iraq. These territories were handed over to the British forces on January 23, 1919. The Ottomans were also forced to leave the parts of the former Russian Empire in the Caucasus (in present-day Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan). They had gained these lands towards the end of World War I after Russia left the war due to the Russian Revolution in 1917.

Under the terms of the Treaty of Sèvres, the partitioning of the Ottoman Empire was made official. The new countries created from the former territories of the Ottoman Empire now number 39.

Turkish War of Independence (1919–1923)

The occupation of Constantinople along with the occupation of İzmir sparked the establishment of the Turkish national movement. This movement won the 1919–1923 Turkish War of Independence under the leadership of Mustafa Kemal Pasha. The Sultanate was abolished on November 1, 1922. The last sultan, Mehmed VI Vahdettin (ruled 1918–1922), left the country on November 17, 1922. The new independent Grand National Assembly of Turkey (GNA) was recognized internationally with the Treaty of Lausanne on July 24, 1923. The GNA officially declared the Republic of Turkey on October 29, 1923. The Caliphate (the religious leadership) was officially abolished several months later, on March 3, 1924. The Sultan and his family were declared unwelcome in Turkey and sent into exile.

Ottoman Dynasty After the Empire Ended

In 1974, descendants of the Ottoman dynasty were allowed to become Turkish citizens by the Grand National Assembly. They were told they could apply. Mehmed Orhan, son of Prince Mehmed Abdul Kadir of the Ottoman Empire, died in 1994. This left the grandson of Ottoman Sultan Abdülhamid II, Ertuğrul Osman, as the oldest living member of the former ruling family. For many years, Osman refused to carry a Turkish passport, calling himself a citizen of the Ottoman Empire. Despite this, he ended any talk of restoring the Ottoman Empire when he told an interviewer "no" to the question of whether he wished the Ottoman Empire to be restored. He was quoted as saying that "democracy works well in Turkey." He returned to Turkey in 1992 for the first time since the exile and became a Turkish citizen with a Turkish passport in 2002.

On September 23, 2009, Osman died at the age of 97 in Istanbul. With his death, the last person born under the Ottoman Empire from the ruling line passed away. In Turkey, Osman was known as "the last Ottoman."

Harun Osmanoğlu, the great-grandson of Abdul Hamid II, is the oldest living member of the former ruling dynasty.

-

The Blue Mosque Sultan Ahmed Mosque (1616)

-

Süleymaniye Mosque (Ottoman imperial mosque-1556)

-

Topkapı Palace (1453)

-

Piri Reis map (1513)

Why the Empire Fell

In many ways, the reasons for the Ottoman Empire's fall were due to tensions between the Empire's different ethnic groups. Also, the various governments struggled to deal with these tensions. The introduction of more cultural rights, civil liberties, and a parliamentary system during the Tanzimat period came too late. It could not reverse the nationalistic and independence-seeking trends that had already started since the early 19th century.

See also

- History of the Republic of Turkey (1923–present)

- Outline of the Ottoman Empire

- Territorial evolution of the Ottoman Empire

- Timeline of the Ottoman Empire

- Wikilala