History of Bulgaria facts for kids

The history of Bulgaria is a long and exciting journey, starting from the very first people who lived on these lands, all the way to modern-day Bulgaria. It also tells the story of the Bulgarian people and where they came from. The oldest signs of humans in Bulgaria are from about 1.4 million years ago! Around 5000 BC, a clever civilization was already making some of the world's first pottery, jewelry, and gold items.

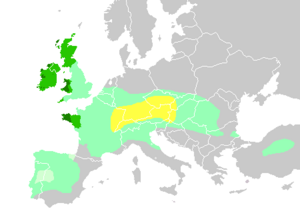

Later, around 3000 BC, the Thracians appeared on the Balkan Peninsula. In the late 6th century BC, parts of what is now eastern Bulgaria came under the Persian Empire. By the 470s BC, the Thracians formed a strong kingdom called the Odrysian Kingdom. This kingdom lasted until 46 BC, when the Roman Empire took control. Over the centuries, some Thracian tribes were also ruled by ancient Macedonians, Greeks, and Celts. These ancient groups eventually mixed with the Slavs, who settled in the area after 500 AD.

In 632 AD, the Bulgars created their own state north of the Black sea, known as Great Bulgaria, led by Kubrat. But pressure from the Khazars caused Great Bulgaria to slowly break apart in the late 600s. One of Kubrat's leaders, Asparuh, led some Bulgar tribes to the Danube delta. They then conquered lands from the Byzantine Empire, expanding their new kingdom into the Balkan peninsula. The important Battle of Ongal in 680, a peace treaty with Byzantium in 681, and the setting up of a permanent Bulgarian capital at Pliska marked the start of the First Bulgarian Empire.

This new state brought together local Byzantine people and migrant people like the Early Slavs under Bulgar rule. Slowly, these groups began to mix. In the centuries that followed, Bulgaria became a powerful empire, ruling the Balkans with its strong military. This led to the development of a unique Bulgarian identity. Its diverse people united under one religion, language, and alphabet, which helped keep Bulgarian national feelings strong despite foreign invasions.

In the 11th century, the First Bulgarian Empire fell apart due to many attacks from the Rus' and Byzantines. It was conquered and became part of the Byzantine Empire until 1185. Then, a big rebellion led by two brothers, Asen and Peter of the Asen dynasty, brought the Bulgarian state back to life as the Second Bulgarian Empire. After reaching its peak in the 1230s, Bulgaria began to decline. This was mainly because its location made it easy for many different groups to attack it at the same time. A peasant rebellion, one of the few successful ones in history, even put a swineherd named Ivaylo on the throne as Tsar. His short rule helped bring back some of Bulgaria's strength.

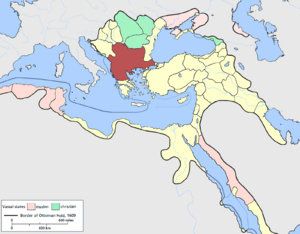

A good period followed after 1300, but it ended in 1371 when disagreements caused Bulgaria to split into three smaller kingdoms. By 1396, they were all taken over by the Ottoman Empire. The Turks removed the Bulgarian nobles and church leaders, and Bulgaria remained part of the Ottoman Empire for the next 500 years.

After 1700, as the Ottoman Empire grew weaker, signs of a Bulgarian revival began to appear. The old Bulgarian noble families were gone, leaving a society of equal peasants with a small but growing group of city dwellers. By the 19th century, the Bulgarian National Revival became a key part of the fight for independence. This led to the failed April uprising in 1876, which then caused the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78 and the Liberation of Bulgaria. The first peace agreement, the Treaty of San Stefano, was rejected by the Great Powers (major European countries). The later Treaty of Berlin limited Bulgaria's lands to Moesia and the area around Sofia. This left many Bulgarians outside the new state's borders, which made Bulgaria very focused on military strength in the region and led it to side with Germany in both World Wars.

After World War II, Bulgaria became a Communist state. Todor Zhivkov was the leader of the Bulgarian Communist Party for 35 years. During this time, the country saw fast economic growth, longer life expectancies, and a greater focus on industry. However, Bulgaria's economic progress ended in the 1980s. The fall of the Communist system in Eastern Europe changed the country's path. A series of problems in the 1990s left much of Bulgaria's industry and farming in ruins. But things started to get better when Simeon Saxe-Coburg-Gotha became prime minister in 2001. Bulgaria joined NATO in 2004 and the European Union in 2007.

Contents

- Ancient Times: Early Humans and Civilizations

- Antiquity: Thracians, Greeks, and Romans

- Migration Period: New Peoples Arrive

- First Bulgarian Empire (681–1018): A Powerful State

- Bulgaria Under Byzantine Rule (1018–1185)

- Second Bulgarian Empire (1185–1396): A New Beginning

- Bulgaria Under Ottoman Rule (1396–1878)

- Third Bulgarian State (1878–1946): A New Nation

- People's Republic of Bulgaria (1946–1991): Communist Rule

- Republic of Bulgaria: Modern Times

- Images for kids

- See also

Ancient Times: Early Humans and Civilizations

The oldest human remains found in Bulgaria are from the Kozarnika cave, dating back about 1.6 million years ago. This cave might hold the earliest evidence of human symbolic behavior ever found.

The earliest homes in Bulgaria, called the Stara Zagora Neolithic dwellings, are from 6,000 BC. They are among the oldest human-made structures discovered. By the end of the Stone Age, cultures like Karanovo, Hamangia, and Vinča developed in what is now Bulgaria, southern Romania, and eastern Serbia. The first known town in Europe, Solnitsata, was in present-day Bulgaria. The Durankulak lake settlement started on a small island around 7000 BC. By 4700/4600 BC, stone buildings were common there, which was unique in Europe.

The eneolithic Varna culture (5000 BC) was the first civilization in Europe with a complex social system. Its most important site is the Varna Necropolis, found in the early 1970s. It helps us understand how early European societies worked, especially through well-preserved burials, pottery, and gold jewelry. The gold rings, bracelets, and ceremonial weapons found in one grave were made between 4,600 and 4200 BC. This makes them the oldest gold items ever discovered anywhere in the world!

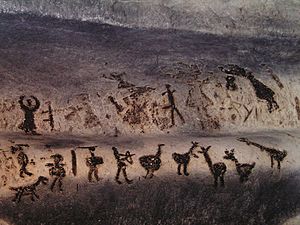

Some of the earliest signs of growing grapes and taming animals are linked to the Bronze Age Ezero culture. The Magura Cave drawings are from the same time, though their exact age is hard to pinpoint.

Antiquity: Thracians, Greeks, and Romans

The Thracians: Ancient People of the Balkans

The first people to leave lasting marks and culture in the Balkan region were the Thracians. Their origin is not fully clear. It's thought that they came from a mix of local people and Indo-Europeans who arrived around 1500 BC. Thracian artists were very skilled, especially in working with gold.

The Thracians were usually not united, but they had an advanced culture even without their own writing system. They could gather strong armies when their separate tribes joined together against outside threats. They mostly lived in small fortified villages, often on hilltops. Even though the idea of a city didn't fully develop until Roman times, there were many larger forts that also served as local markets. Generally, Thracians avoided city life, even with Greek colonies like Byzantium and Apollonia nearby.

Persian Rule and the Odrysian Kingdom

Parts of what is now Bulgaria came under the Persian Empire around 512-511 BC. The Persian army, led by Darius the Great, conquered several Thracian peoples and coastal Greek cities. They even defeated the powerful Paeonians. Most of eastern Bulgaria remained under Persian control until 479 BC.

Around 470 BC, King Teres united many Thracian tribes to form the Odrysian kingdom. This kingdom became very strong under kings like Sitalces (431–424 BC) and Cotys I (383–359 BC). Sitalces even invaded Macedon with a huge army of 150,000 warriors.

Macedonian and Celtic Influence

Later, the Macedonian Empire took over the Odrysian kingdom. Thracians then became part of the armies of Philip II and Alexander III (the Great) in their campaigns.

Around 298 BC, Celtic tribes arrived in what is now Bulgaria. They fought the Macedonians but kept moving forward. Many Thracian groups, already weakened by Macedonian rule, fell under Celtic control. In 279 BC, a Celtic army led by Comontorius conquered Thrace and set up the kingdom of Tylis in eastern Bulgaria. This kingdom lasted until 212 BC, when the Thracians took back control. Small groups of Celts remained in Western Bulgaria, like the serdi tribe, from whom the ancient name of Sofia, Serdica, comes. The Celts stayed for over a century, but their impact on the region was small.

Roman Period: New Rulers

In 188 BC, the Romans invaded Thrace. Fighting continued until 46 AD, when Rome finally conquered the region and made it the province of Thracia.

By the 4th century, the Thracians had a mixed identity. They were Christian "Romans" but kept some of their old traditions. Thraco-Romans became an important group in the region, and some even became military leaders and emperors, like Galerius and Constantine I the Great. Cities grew, especially Serdika (modern Sofia), because of its many mineral springs. People from all over the empire moved in, adding to the local culture. Temples to Egyptian gods like Osiris and Isis have been found near the Black Sea coast.

Migration Period: New Peoples Arrive

In the 4th century, a group of Goths settled in northern Bulgaria. There, a Gothic bishop named Ulfilas translated the Bible from Greek to Gothic, creating the Gothic alphabet. This was the first book written in a Germanic language. The first Christian monastery in Europe was founded in 344 near modern-day Chirpan.

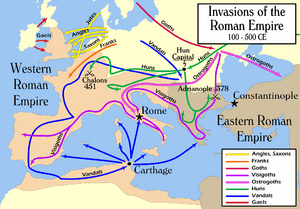

Because most of the local people lived in the countryside, Roman control was weak. In the 5th century, Attila's Huns attacked Bulgaria and destroyed many Roman settlements. By the end of the 6th century, Avars regularly raided northern Bulgaria, which led to the large-scale arrival of the Slavs.

During the 6th century, traditional Greek and Roman culture was still important, but Christian ideas and culture became dominant. From the 7th century, Greek became the main language in the Eastern Roman Empire's government and church.

Slavs: Settling the Land

The Slavs came from their homeland in Eastern Europe in the early 6th century. They spread across much of eastern Central Europe, Eastern Europe, and the Balkans. The easternmost South Slavs settled in what is now Bulgaria during the 6th century. Most of the Thracians eventually adopted Greek or Roman culture. A part of the eastern South Slavs mixed with them before the Bulgar leaders included these people into the First Bulgarian Empire.

Bulgars: From Central Asia to the Balkans

The Bulgars were a group of people from Central Asia. From the 2nd century onwards, they lived in the plains north of the Caucasus mountains and around the Volga river. One branch of them later founded the First Bulgarian Empire. The Bulgars were led by hereditary khans and had several noble families who formed a ruling class. They believed in many gods, but mainly worshipped the main god, Tangra.

Old Great Bulgaria: A Short-Lived Kingdom

In 632, Khan Kubrat united three large Bulgar tribes, forming a country historians now call Great Bulgaria. This country was located between the lower Danube river, the Black Sea, the Azov Sea, the Kuban river, and the Donets river. Its capital was Phanagoria.

In 635, Kubrat made a peace treaty with the Byzantine Emperor Heraclius, which expanded the Bulgar kingdom further into the Balkans. Kubrat was even given the title Patrician by Heraclius. However, the kingdom did not last long after Kubrat's death. After wars with the Khazars, the Bulgars were defeated. They moved south, north, and mainly west into the Balkans, where most other Bulgar tribes were already living under Byzantine rule.

One of Kubrat's sons, Kotrag, led nine Bulgar tribes north along the Volga river, creating the Kingdom of the Volga Bulgars in the late 7th century. This kingdom became an important trade and cultural center. Another son, Asparuh (Kotrag's brother), moved west. After a successful war with Byzantium in 680, Asparuh's khanate conquered Scythia Minor. It was recognized as an independent state by the Byzantine Empire in 681. This year is usually seen as the start of present-day Bulgaria, and Asparuh is considered its first ruler.

First Bulgarian Empire (681–1018): A Powerful State

Under Asparuh, Bulgaria expanded southwest after the Battle of Ongal, forming Danubian Bulgaria. Before this, the lands of modern Bulgaria were part of the Roman Empire, with a mix of Byzantine Greeks, Thracians, and Dacians. Many spoke Greek or Latin. Several waves of Slavic migration in the 6th and early 7th centuries changed the population greatly, making the region mostly Slavic.

Asparuh's son, Tervel, became ruler in the early 8th century. The Byzantine Emperor Justinian II asked Tervel for help to get his throne back. Tervel helped and received land and gold, along with the Byzantine title "Caesar". Later, the emperor tried to attack Bulgaria but was defeated. After Justinian II's death, the Bulgarians continued their attacks on the empire, reaching Constantinople in 716. The new emperor, Theodosius III, had to sign a peace treaty with Tervel.

In 717, Emperor Leo III the Isaurian faced a huge army of 100,000 Arabs attacking Constantinople. Relying on his treaty with Bulgaria, the emperor asked Khan Tervel for help. Tervel agreed, and the Arabs were crushed outside the city walls. This battle was very important for stopping the Arab advance into Europe. After Tervel's rule, there were many changes in leadership, leading to instability.

Decades later, Telerig ruled Bulgaria (768). He tricked the Byzantine Emperor into revealing his spies in the capital Pliska and then had them killed. His rule brought an end to the political problems.

Under Krum (802–814), Bulgaria expanded greatly to the northwest and south. It took over lands between the Danube and Moldova rivers, all of present-day Romania, and even Sofia in 809 and Adrianople in 813, threatening Constantinople. Krum made new laws to help the poor and strengthen society in his large state.

During the rule of Khan Omurtag (814–831), the borders with the Frankish Empire were set along the middle Danube. A magnificent palace, temples, and other buildings were constructed in the Bulgarian capital Pliska, mostly from stone and brick. Omurtag was harsh towards Christians.

Christianity and the Golden Age

Under Boris I, Bulgaria officially became Christian. The Ecumenical Patriarch (the head of the Eastern Orthodox Church) agreed to allow an independent Bulgarian Archbishop in Pliska. Missionaries from Constantinople, Cyril and Methodius, created the Glagolitic alphabet. This alphabet was adopted in Bulgaria around 886. The alphabet and the Old Bulgarian language led to a rich period of writing and culture, centered around the Preslav and Ohrid Literary Schools, which Boris I established in 886.

In the early 9th century, a new alphabet called Cyrillic was developed at the Preslav Literary School, based on the Glagolitic alphabet. Some believe it was created at the Ohrid Literary School by Saint Climent of Ohrid.

By the late 9th and early 10th centuries, Bulgaria stretched to Epirus and Thessaly in the south, Bosnia in the west, and controlled all of present-day Romania and eastern Hungary to the north. A Serbian state became dependent on the Bulgarian Empire. Under Tsar Simeon I of Bulgaria (Simeon the Great), who studied in Constantinople, Bulgaria again became a serious threat to the Byzantine Empire. He wanted to take Constantinople and become emperor of both Bulgarians and Greeks. He fought many wars with the Byzantines during his long rule (893–927). By the end of his reign, Bulgaria was the most powerful state in Southeast Europe. Simeon called himself "Tsar (Caesar) of the Bulgarians and the Romans," a title recognized by the Pope. The capital Preslav was said to rival Constantinople, and the new independent Bulgarian Orthodox Church became the first new patriarchate outside the main five. Bulgarian translations of Christian texts spread throughout the Slavic world.

Decline of the First Empire

After Simeon's death, Bulgaria was weakened by wars with Croatians, Magyars, Pechenegs, and Serbs, and the spread of the Bogomil heresy. Two invasions by the Kievan Rus' and Byzantines led to the Byzantine army taking the capital Preslav in 971. Under Samuil, Bulgaria recovered somewhat and conquered Serbia.

In 986, the Byzantine emperor Basil II began a campaign to conquer Bulgaria. After decades of war, he decisively defeated the Bulgarians in 1014 and finished his campaign four years later. In 1018, after the death of the last Bulgarian Tsar, Ivan Vladislav, most of Bulgaria's nobles chose to join the Eastern Roman Empire. Bulgaria lost its independence and was under Byzantine rule for over a century and a half.

Bulgaria Under Byzantine Rule (1018–1185)

For the first ten years after Byzantine rule began, there isn't much evidence of major resistance from the Bulgarian people or nobles. This might be because Emperor Basil II made some promises to the Bulgarian nobles to gain their loyalty.

Basil II promised that Bulgaria would remain within its old borders and did not officially remove the local Bulgarian nobles from power. They became part of the Byzantine nobility. Also, special royal decrees from Basil II recognized the autocephaly (independence) of the Bulgarian Archbishopric of Ohrid and protected its lands and privileges.

After Basil II died, the empire became unstable. In 1040, Peter Delyan led a large rebellion, but he failed to bring back the Bulgarian state and was killed. Later, the Komnenos dynasty came to power and stopped the empire's decline. During this time, the Byzantine state had a century of stability and progress.

In 1180, the last strong Komnenos emperor, Manuel I Komnenos, died. He was replaced by the less capable Angeloi dynasty, which allowed some Bulgarian nobles to start an uprising. In 1185, Peter and Asen, who were leading nobles, led a revolt against Byzantine rule. Peter declared himself Tsar Peter II. The next year, the Byzantines had to recognize Bulgaria's independence. Peter called himself "Tsar of the Bulgars, Greeks and Wallachians."

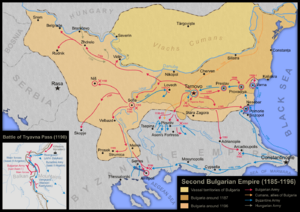

Second Bulgarian Empire (1185–1396): A New Beginning

The restored Bulgaria covered the area between the Black Sea, the Danube, and Stara Planina mountains. It also included parts of eastern Macedonia, Belgrade, and the Morava valley, and controlled Wallachia. Tsar Kaloyan (1197–1207) made an agreement with the Papacy (the Pope), which recognized him as "Rex" (King), though he wanted to be called "Emperor" or "Tsar". He fought wars against the Byzantine Empire and the Knights of the Fourth Crusade, conquering large parts of Thrace, the Rhodopes, and all of Macedonia.

In the Battle of Adrianople in 1205, Kaloyan defeated the forces of the Latin Empire, limiting its power from the very beginning. Under Ivan Asen II (1218–1241), Bulgaria once again became a regional power, taking over Belgrade and Albania. In 1230, he called himself "faithful Tsar and autocrat of the Bulgarians."

The Bulgarian Orthodox Patriarchate (the highest church authority) was restored in 1235 with the approval of all eastern Patriarchates, ending the union with the Papacy. Ivan Asen II was known as a wise and kind ruler. He started relations with the Catholic west, especially Venice and Genoa, to reduce Byzantine influence. Tarnovo became a major economic and religious center, seen as a "Third Rome". Like Simeon the Great in the First Empire, Ivan Asen II expanded Bulgaria's territory to the coasts of three seas (Adriatic, Aegean, and Black).

The country's military and economic strength declined after the Asen dynasty ended in 1257. Bulgaria faced internal conflicts, constant Byzantine and Hungarian attacks, and Mongol domination. Tsar Teodore Svetoslav (1300–1322) temporarily brought back Bulgaria's prestige. However, political instability continued to grow, and Bulgaria slowly lost territory. This led to a peasant rebellion led by the swineherd Ivaylo, who managed to defeat the Tsar's forces and become Tsar himself.

Ottoman Invasions and the End of Independence

In the 14th century, a weakened Bulgaria faced a new threat from the south: the Ottoman Turks, who crossed into Europe in 1354. By 1371, disagreements among the feudal landlords and the spread of Bogomilism caused the Second Bulgarian Empire to split into three small kingdoms—Vidin, Tarnovo, and Karvuna—and several smaller independent areas. These states fought among themselves and with Byzantines, Hungarians, Serbs, Venetians, and Genoese.

The Ottomans faced little resistance from these divided and weak Bulgarian states. In 1362, they captured Philippopolis (Plovdiv), and in 1382, they took Sofia. The Ottomans then turned to the Serbs, whom they defeated at Kosovo Polje in 1389. In 1393, the Ottomans occupied Tarnovo after a three-month siege. In 1396, the Tsardom of Vidin was also invaded, bringing the Second Bulgarian Empire and Bulgarian independence to an end.

Bulgaria Under Ottoman Rule (1396–1878)

In 1393, the Ottomans captured Tarnovo, the capital of the Second Bulgarian Empire. In 1396, the Vidin Tsardom fell after a Christian crusade was defeated at the Battle of Nicopolis. With this, the Ottomans finally conquered and occupied Bulgaria.

A crusade of Polish and Hungarian forces tried to free Bulgaria and the Balkans in 1444, but the Turks won at the battle of Varna.

The new Ottoman rulers removed Bulgarian institutions and merged the separate Bulgarian Church into the Ecumenical Patriarchate in Constantinople. Turkish authorities destroyed most medieval Bulgarian fortresses to prevent rebellions. Large towns and areas where Ottoman power was strong remained with few people until the 19th century.

The Ottomans usually did not force Christians to become Muslims. However, there were cases of forced conversion, especially in the Rhodopes mountains. Bulgarians who became Muslims, called the Pomaks, kept their Bulgarian language, clothes, and some customs that fit with Islam.

The Ottoman system began to decline by the 17th century and almost completely fell apart by the end of the 18th century. The central government became weak, allowing local Ottoman landowners to gain control over different regions. In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, the Balkan Peninsula became very chaotic.

Bulgarian tradition calls this period the kurdjaliistvo: armed groups of Turks called kurdjalii caused problems in the area. Many peasants fled from the countryside to towns, hills, or forests. Some even fled across the Danube to Moldova, Wallachia, or southern Russia. The decline of Ottoman rule also allowed a slow revival of Bulgarian culture, which became important for the idea of national freedom.

Conditions slowly improved in some areas in the 19th century. Some towns, like Gabrovo and Koprivshtitsa, became prosperous. Bulgarian peasants actually owned their land, even though it officially belonged to the sultan. The 19th century also brought better communication, transportation, and trade. The first factory in Bulgarian lands opened in Sliven in 1834, and the first railway (between Rousse and Varna) started in 1865.

Bulgarian nationalism began to grow in the early 19th century, influenced by Western ideas like liberalism and nationalism from the French Revolution. The Greek revolt against the Ottomans in 1821 also influenced educated Bulgarians. However, Greek influence was limited because Bulgarians resented Greek control over the Bulgarian Church. The fight to revive an independent Bulgarian Church was what first sparked Bulgarian nationalist feelings.

In 1870, a Bulgarian Exarchate (an independent church) was created by a special order from the Sultan. The first Bulgarian Exarch, Antim I, became the natural leader of the rising nation. The Constantinople Patriarch excommunicated the Bulgarian Exarchate, which made Bulgarians even more determined for independence. A fight for political freedom from the Ottoman Empire began, led by groups like the Bulgarian Revolutionary Central Committee and the Internal Revolutionary Organisation, with leaders like Vasil Levski, Hristo Botev, and Lyuben Karavelov.

April Uprising and the Russo-Turkish War (1870s)

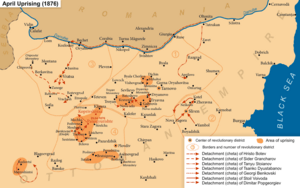

In April 1876, the Bulgarians rebelled in the April Uprising. The revolt was not well organized and started too early. It was mostly in the region of Plovdiv, though some areas in northern Bulgaria, Macedonia, and near Sliven also took part. The Ottomans crushed the uprising, bringing in irregular troops who killed many people. Countless villages were looted, and tens of thousands were killed, mostly in towns like Batak, Perushtitsa, and Bratsigovo.

These terrible events caused a strong reaction among liberal Europeans like William Ewart Gladstone, who spoke out against the "Bulgarian Horrors." Many European thinkers and public figures supported this campaign. The strongest reaction came from Russia. The outrage caused by the April Uprising led to the Constantinople Conference of the Great Powers in 1876–77.

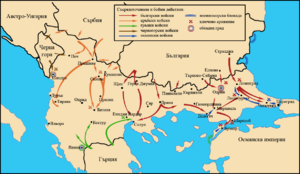

Turkey's refusal to follow the conference's decisions gave Russia a chance to achieve its goals regarding the Ottoman Empire. Russia declared war on the Ottomans in April 1877. Bulgarians also fought alongside the advancing Russians. Russia set up a temporary government in Bulgaria. The Russian army and Bulgarian volunteers decisively defeated the Ottomans at Shipka Pass and Pleven. By January 1878, they had freed much of the Bulgarian lands.

Third Bulgarian State (1878–1946): A New Nation

The Treaty of San Stefano was signed on March 3, 1878. It created an independent Bulgarian principality on the lands of the Second Bulgarian Empire, including Moesia, Thrace, and Macedonia. Although officially autonomous, it acted independently. However, other Great Powers feared a large Russian-backed state in the Balkans and did not agree to the treaty.

As a result, the Treaty of Berlin (1878) changed the earlier agreement. It limited Bulgaria's new territory to the area between the Danube and the Stara Planina mountains, with its capital at Veliko Turnovo and including Sofia. This left many ethnic Bulgarians outside the new country's borders. This situation shaped Bulgaria's military-focused foreign policy and its involvement in four wars in the first half of the 20th century.

Alexander of Battenberg, a German prince, became the first ruler of modern Bulgaria in 1879. Everyone expected Bulgaria to be a Russian ally, but instead, it became a barrier against Russian expansion and worked with the British. Bulgaria was attacked by Serbia in 1885 but defeated the invaders. This earned it respect from the major powers and challenged Russia. In response, Russia forced Prince Alexander to step down in 1886.

Stefan Stambolov (1854-1895) served as regent and then prime minister for the new ruler, Ferdinand I of Bulgaria (prince 1887–1908, tsar 1908-1918). Stambolov believed Russia's liberation of Bulgaria was an attempt to make Bulgaria its protectorate. His policy aimed to keep Bulgaria independent at all costs. During his leadership, Bulgaria changed from an Ottoman province into a modern European state. Stambolov started a new foreign policy for Bulgaria, independent of any great power's interests. His main goal was to unite the Bulgarian nation into one state, including all the territories granted by the Sultan in 1870. Stambolov worked closely with the Sultan to support Bulgarian national spirit in Macedonia and oppose Greek and Serbian propaganda. He also got loans from Western European countries to develop Bulgaria's economy and military.

Bulgaria emerged from Turkish rule as a poor, farming country with little industry. Most land was owned by small farmers, and peasants made up 80% of the population in 1900. The government promoted modernization, especially building schools. By 1910, there were many elementary and secondary schools, and a university was established in 1888 (renamed the University of Sofia in 1904). The first decade of the century saw steady growth in cities. Sofia's population grew six times, from 20,000 in 1878 to 120,000 in 1912.

The Balkan Wars: Conflicts Over Territory

After gaining independence, Bulgaria became very focused on its military. It was often called "the Balkan Prussia" because it wanted to change the Treaty of Berlin through war. The division of lands in the Balkans by the Great Powers, without considering ethnic groups, caused unhappiness in Bulgaria and its neighbors. In 1911, Prime Minister Ivan Geshov formed an alliance with Greece and Serbia to attack the Ottomans together and redraw borders based on ethnic lines.

In February 1912, a secret treaty was signed between Bulgaria and Serbia, and in May 1912, a similar agreement was made with Greece. Montenegro also joined. The treaties planned to divide Macedonia and Thrace among the allies, but the exact borders were unclear. When the Ottoman Empire refused to make reforms, the First Balkan War began in October 1912. The allies easily defeated the Ottomans and took most of their European territory.

Bulgaria suffered the most casualties but also claimed the largest territories. Serbia disagreed and refused to leave the land they had taken in northern Macedonia. They argued that the Bulgarian army had not achieved its goals at Adrianople and that the pre-war agreement on dividing Macedonia needed to be changed. Some in Bulgaria wanted to go to war with Serbia and Greece over this.

In June 1913, Serbia and Greece formed a new alliance against Bulgaria. Tsar Ferdinand declared war on Serbia and Greece on June 29. The Serbian and Greek forces initially pushed back, but they quickly gained the upper hand and forced Bulgaria to retreat. The fighting was very harsh, with many casualties. Soon after, Romania entered the war on the side of Greece and Serbia, attacking Bulgaria from the north. The Ottoman Empire also attacked from the southeast to regain lost lands.

Facing war on three fronts, Bulgaria asked for peace. It had to give up most of its land in Macedonia to Serbia and Greece, Adrianople to the Ottoman Empire, and Southern Dobruja to Romania. The two Balkan wars greatly destabilized Bulgaria, stopping its economic growth and causing 58,000 deaths and over 100,000 wounded. The anger over being "betrayed" by its former allies strengthened political groups that demanded Macedonia be returned to Bulgaria.

World War I: Siding with the Central Powers

After the Balkan Wars, Bulgarians felt betrayed by Russia and the Western powers. The government of Vasil Radoslavov allied Bulgaria with the German Empire and Austria-Hungary, even though this meant allying with the Ottomans, Bulgaria's traditional enemy. But Bulgaria now had no claims against the Ottomans, while Serbia, Greece, and Romania (allies of Britain and France) held lands that Bulgaria considered its own.

Bulgaria stayed out of the first year of World War I to recover from the Balkan Wars. Germany and Austria realized they needed Bulgaria's help to defeat Serbia and open supply lines to Turkey. Bulgaria demanded major territorial gains, especially Macedonia. Tsar Ferdinand decided to side with Germany and Austria and signed an alliance with them in September 1915. This alliance envisioned Bulgaria dominating the Balkans after the war.

Bulgaria declared war on Serbia in October 1915. Britain, France, and Italy responded by declaring war on Bulgaria. Allied with Germany, Austria-Hungary, and the Ottomans, Bulgaria won military victories against Serbia and Romania. It occupied much of Macedonia, advanced into Greek Macedonia, and took Dobruja from Romania. By 1917, Bulgaria had a large army of 1,200,000 soldiers and caused heavy losses to its enemies.

However, the war soon became unpopular with most Bulgarians. They suffered great economic hardship and disliked fighting fellow Orthodox Christians alongside the Muslim Ottomans. The Russian Revolution of February 1917 greatly affected Bulgaria, spreading anti-war and anti-monarchy feelings among soldiers and in cities. In June, Radoslavov's government resigned. Mutinies broke out in the army, and a republic was declared.

Between the World Wars

In September 1918, Tsar Ferdinand stepped down in favor of his son Boris III to prevent anti-monarchy revolutionary movements. Under the Treaty of Neuilly (November 1919), Bulgaria gave its Aegean coastline to Greece, recognized Yugoslavia, gave almost all its Macedonian territory to the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, and had to give Dobruja back to Romania. The country also had to reduce its army and pay large amounts of money. Bulgarians often call the results of this treaty the "Second National Catastrophe."

Elections in March 1920 gave the Agrarians a large majority, and Aleksandar Stamboliyski formed Bulgaria's first peasant government. He faced huge social problems but managed to carry out many reforms. However, opposition from the middle and upper classes, landowners, and army officers remained strong. In March 1923, Stamboliyski signed an agreement with Yugoslavia, recognizing the new border and agreeing to suppress the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (VMRO), which wanted war to regain Macedonia.

This caused a nationalist reaction, and a coup d'état on June 9, 1923, led to Stamboliyski's assassination. An extreme right-wing government under Aleksandar Tsankov took power, supported by the army and VMRO. This government was very harsh against Agrarians and Communists. In 1926, Tsar Boris persuaded Tsankov to resign, and a more moderate government took office. A popular alliance, including the re-organized Agrarians, won the elections of 1931.

In May 1934, another coup removed the popular alliance from power and established an authoritarian military government led by Kimon Georgiev. A year later, Tsar Boris managed to remove the military government, bringing back a form of parliamentary rule (without political parties) under his strict control. The Tsar's regime declared neutrality but slowly moved towards an alliance with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy.

World War II: Caught in the Conflict

When World War II began, the government of the Kingdom of Bulgaria under Bogdan Filov declared neutrality. They hoped to gain land without fighting, especially in areas with many Bulgarians that had been lost after the Balkan Wars and World War I. However, Bulgaria's central location in the Balkans meant it would face strong pressure from both sides of the war.

Bulgaria successfully negotiated to get back Southern Dobruja from Romania in the Axis-supported Treaty of Craiova on September 7, 1940. This strengthened Bulgarian hopes of solving territorial problems without direct involvement in the war. However, Bulgaria was forced to join the Axis powers in 1941 when German troops, preparing to invade Greece from Romania, reached the Bulgarian borders and demanded permission to pass through. Threatened by direct military conflict, Tsar Boris III had no choice but to join the fascist bloc, which became official on March 1, 1941. There was little public opposition because the Soviet Union had a non-aggression pact with Germany. However, the king refused to hand over Bulgarian Jews to the Nazis, saving 50,000 lives.

Bulgaria did not join the German invasion of the Soviet Union that began on June 22, 1941, nor did it declare war on the Soviet Union. However, the Bulgarian Navy was involved in some small fights with the Soviet Black Sea Fleet, which attacked Bulgarian ships. Also, Bulgarian armed forces in the Balkans fought various resistance groups. Germany forced the Bulgarian government to declare a symbolic war on the United Kingdom and the United States on December 13, 1941. This led to the bombing of Sofia and other Bulgarian cities by Allied planes.

On August 23, 1944, Romania left the Axis Powers and declared war on Germany, allowing Soviet forces to cross its territory to reach Bulgaria. On September 5, 1944, the Soviet Union declared war on Bulgaria and invaded. Within three days, the Soviets occupied northeastern Bulgaria and the key port cities of Varna and Burgas. Meanwhile, on September 5, Bulgaria declared war on Nazi Germany. The Bulgarian Army was ordered not to resist.

On September 9, 1944, a coup overthrew the government, replacing it with a government led by the Fatherland Front. On September 16, 1944, the Soviet Red Army entered Sofia. The Bulgarian Army won several victories against German forces during operations in Kosovo and at Stratsin.

People's Republic of Bulgaria (1946–1991): Communist Rule

During this period, the country was called the "People's Republic of Bulgaria" (PRB) and was ruled by the Bulgarian Communist Party (BCP). The BCP later changed its name to the "Bulgarian Socialist Party" in 1990.

Communist leader Dimitrov had been in exile, mostly in the Soviet Union, since 1923. He was close to Stalin and held high positions. Dimitrov was arrested in Berlin and showed great courage during the Reichstag fire trial of 1933. Stalin made him head of the Comintern.

After 1944, he was also close to the Yugoslav Communist leader Tito and believed that Yugoslavia and Bulgaria should form a federation. Stalin did not like this idea. There have been suspicions that Dimitrov's sudden death in Moscow in July 1949 was not accidental, though it has never been proven. This happened around the time Stalin expelled Tito from the Cominform, and was followed by a "Titoist" witch hunt in Bulgaria. This led to the trial and execution of Deputy Prime Minister Traicho Kostov. The elderly Prime Minister Vasil Kolarov died in January 1950, and power then went to Vulko Chervenkov, a Stalinist.

Bulgaria's Stalinist period lasted less than five years. Under Chervenkov, farming was organized into collective farms, and a huge industrialization campaign began. Bulgaria adopted a centrally planned economy, like other states in the COMECON group. In the mid-1940s, Bulgaria was mainly a farming country, with about 80% of its people in rural areas. In 1950, diplomatic relations with the U.S. were broken off. But Chervenkov's support in the Communist Party was too small to last long after Stalin died in March 1953. In March 1954, Chervenkov was removed as Party Secretary and replaced by Todor Zhivkov. Chervenkov remained Prime Minister until April 1956.

Bulgaria experienced fast industrial development from the 1950s onwards. From the 1960s, the country's economy changed greatly. Although there were still problems like poor housing, modernization was happening. The country then focused on high technology, a sector that made up 14% of its GDP between 1985 and 1990. Its factories produced computer parts and industrial robots.

During the 1960s, Zhivkov started reforms and tried some market-oriented policies. By the mid-1950s, living standards rose significantly. In 1957, collective farm workers received the first agricultural pension and welfare system in Eastern Europe. Lyudmila Zhivkova, Todor Zhivkov's daughter, promoted Bulgaria's culture and arts worldwide. A campaign in the late 1980s against ethnic Turks led to about 300,000 Bulgarian Turks moving to Turkey. This caused a big drop in farm production due to the loss of workers.

Republic of Bulgaria: Modern Times

By the late 1980s, when Mikhail Gorbachev's reforms in the Soviet Union began to affect Bulgaria, the Communists were too weak to resist demands for change for long. In November 1989, demonstrations about environmental issues were held in Sofia, and these soon grew into a general call for political reform. The Communists reacted by removing Zhivkov and replacing him with Petar Mladenov, but this only gave them a short break.

In February 1990, the Communist Party willingly gave up its monopoly on power. In June 1990, the first free elections since 1931 were held. The Communist Party, now without its hardliner wing and renamed the Bulgarian Socialist Party, returned to power. In July 1991, a new Constitution was adopted. It set up a parliamentary republic with a directly elected President and a Prime Minister responsible to the parliament.

Like other former Communist countries in Eastern Europe, Bulgaria found the change to capitalism harder than expected. The anti-Communist Union of Democratic Forces (UDF) took office. Between 1992 and 1994, the government privatized land and industry by giving shares in state-owned companies to all citizens. But this also led to massive unemployment as industries that couldn't compete failed. The Socialists presented themselves as defenders of the poor against the problems of the free market.

The negative reaction against economic reform allowed Zhan Videnov of the BSP to take office in 1995. By 1996, the BSP government also faced difficulties. In the presidential election that year, the UDF's Petar Stoyanov was elected. In 1997, the BSP government collapsed, and the UDF came to power. However, unemployment remained high, and people became increasingly unhappy with both parties.

On June 17, 2001, Simeon II, the son of Tsar Boris III and former Head of State (as Tsar of Bulgaria from 1943 to 1946), won a close victory in elections. His party, the National Movement Simeon II, won 120 of the 240 seats in Parliament. Simeon's popularity quickly declined during his four years as Prime Minister. The BSP won the election in 2005 but had to form a coalition government. In the parliamentary elections in July 2009, Boyko Borisov's center-right party, Citizens for European Development of Bulgaria, won almost 40% of the votes.

Since 1989, Bulgaria has held multi-party elections and privatized its economy. However, economic problems and corruption have caused over 800,000 Bulgarians, including many skilled professionals, to leave the country in a "brain drain". The reforms in 1997 brought positive economic growth, but also led to more social inequality. The political and economic system after 1989 largely failed to improve living standards or create economic growth. A 2009 survey showed that 76% of Bulgarians were unhappy with democracy, 63% thought free markets did not make people better off, and only 11% believed ordinary people had benefited from the changes in 1989. The average quality of life and economic performance remained lower than during the socialist era well into the early 2000s.

Bulgaria became a member of NATO in 2004 and of the European Union in 2007. In 2010, it was ranked 32nd out of 181 countries in the Globalization Index. Freedom of speech and the press are respected by the government (as of 2015), but many media outlets are influenced by advertisers and owners with political goals. Polls seven years after joining the EU found that only 15% of Bulgarians felt they had personally benefited from membership.

Images for kids

-

Yamnaya Steppe Pastoralists expansions

-

The Achaemenid Empire at its greatest territorial extent, under the rule of Darius I (522 BC–486 BC)

-

The Odrysian kingdom under king Sitalces (around 431–424 BC)

-

Conquers of Alexander the Great

-

Alexander’s successors states - in orange are the lands of the King of Thrace, Asia Minor and Macedon Lysimachus

-

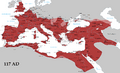

Roman Empire under Trajan (117 AD)

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Bulgaria para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Bulgaria para niños

- Timeline of Bulgarian history

- Hominid dispersals in Europe

- Cradle of civilization

- Neolithic Revolution

- Neolithic Europe

- Thracians

- Moesi

- Getae

- List of ancient Daco-Thracian peoples and tribes

- Dacians

- Paeonia (kingdom)

- Scythians

- Classical Antiquity

- Timeline of Varna

- Philippopolis (Thrace)

- Celtic settlement of Southeast Europe

- List of archaeological sites by country

- History of Sofia

- Edict of Serdica

- Ancient Roman architecture

- Early centers of Christianity

- List of oldest known surviving buildings

- List of oldest church buildings

- Fresco

- Migration Period

- Gothic Bible

- Bulgarian Empire

- Golden Age of medieval Bulgarian culture

- Early Cyrillic alphabet

- Balkan–Danubian culture

- Bulgarian–Latin wars

- Tsarevets (fortress)

- Architecture of the Tarnovo Artistic School

- Tarnovo Literary School

- Baba Vida

- Byzantine–Bulgarian wars

- National awakening of Bulgaria

- Bulgarian unification

- List of Bulgarian monarchs

- Medieval Bulgarian army

- Medieval Bulgarian navy

- Bulgarian lands across the Danube

- Bulgarian language

- Bulgarian dialects

- List of predecessors of sovereign states in Europe

- List of sovereign states by date of formation § Europe

- Timeline of sovereign states in Europe

- List of empires

- List of medieval great powers

- List of oldest continuously inhabited cities

- History of the Balkans

- History of the Mediterranean region

- History of Europe