Odrysian kingdom facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Odrysian Kingdom

|

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 480 BC–30 BC | |||||||||||||

|

Labrys

|

|||||||||||||

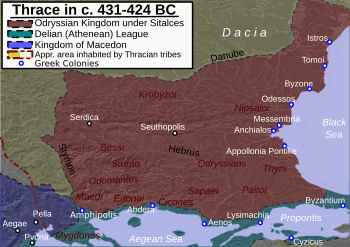

The Odrysian kingdom during its peak under king Sitalces

|

|||||||||||||

| Capital | Seuthopolis (c. 330–250 BC) |

||||||||||||

| Common languages | Thracian Greek (used in writing and among trade and administration) |

||||||||||||

| Religion | Thracian polytheism | ||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||

| Historical era | Classical antiquity | ||||||||||||

|

• Foundation

|

c. 480 BC | ||||||||||||

|

• Conquest by Philip II of Macedon

|

340 BC | ||||||||||||

|

• Rebellion of Seuthes III

|

c. 330 | ||||||||||||

|

• Destruction of Seuthopolis

|

c. 250 | ||||||||||||

|

• Conquest of Odrysian heartlands by the Sapaeans

|

30 BC | ||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

| Today part of | Bulgaria Greece Turkey Romania |

||||||||||||

The Odrysian Kingdom (Βασίλειον Ὀδρυσῶν) was an ancient Thracian kingdom. It existed from the early 5th century BC until at least the mid-3rd century BC. This kingdom covered much of what is now Bulgaria, parts of southeastern Romania, Northern Greece, and European Turkey. The Odrysian people were the most powerful group in this kingdom. It was the first large political state in the eastern Balkans. For a long time, it did not have a fixed capital city. Later, Seuthopolis became its capital in the late 4th century BC.

King Teres I founded the Odrysian kingdom. He took advantage of the Persian Empire's power weakening in Europe. This happened after their failed invasion of Greece in 480-79 BC. Teres and his son Sitalces worked to expand the kingdom. This made it one of the strongest states of its time. For much of its early history, it was an ally of Athens. It even joined Athens in the Peloponnesian War. By 400 BC, the kingdom started to show signs of weakness. However, the skilled king Cotys I brought a short period of strength. This lasted until he was murdered in 360 BC.

After Cotys I's death, the kingdom broke apart. Southern and central Thrace were split among three Odrysian kings. The northeast came under the control of the Getae kingdom. The three Odrysian kingdoms were eventually conquered by the rising Kingdom of Macedon. This happened under Philip II in 340 BC. A smaller Odrysian state was later revived around 330 BC by Seuthes III. He founded a new capital called Seuthopolis. This city was important until the mid-3rd century BC. After this, there is not much clear evidence of an Odrysian state. The Odrysian heartland was eventually taken over by the Sapaean kingdom in the late 1st century BC. This Sapaean kingdom then became a Roman province in 45/6 AD.

Contents

- A Look at the Past

- The Odrysian Kingdom Begins

- The Odrysians and the Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC)

- Challenges and a Brief Comeback

- The Kingdom Falls Apart

- Odrysian Revival and Decline

- How Odrysian Kings Ruled

- Odrysian Army and Warfare

- Culture and Art

- Archaeology Discoveries

- List of Odrysian Kings

- Odrysian Treasures

- Literature

- See also

A Look at the Past

How We Know About Thrace

Since the ancient Thracians did not write their own history, we learn about them from other sources. These include archaeological finds, coins, and writings from ancient Greek historians. These historians described the Thracians as a very large group of people. They said their country, Thrace, was huge.

Thrace was divided into a northern and southern part. These parts had different cultures. Southern Thrace had fertile valleys and was near the Aegean Sea and Black Sea. Northern Thrace was defined by the Danube river and the Carpathian Mountains. Thrace also reached into what is now northwestern Turkey.

Thracians lived in this area as early as 2000 BC. They are even mentioned in the famous stories of Homer. Greek colonists started settling along the Thracian coast in the 7th and 6th centuries BC. They founded many towns like Thasos and Byzantion. We don't know much about the political history of Thracian tribes from this time. However, it's known that in the late 6th century, Athenian settlers met a "king of Thrace." This king might have been a leader before the Odrysian kings.

Persia's Influence in Thrace

Around 513 BC, the powerful Persian Achaemenid Empire sent an army across the Bosporus. Their goal was to punish the Scythians who lived north of the Black Sea. Most eastern Thracian tribes gave up peacefully. However, the Getai tribe was defeated. More Persian expeditions followed. But they only managed to control the Aegean coast.

The Persians likely did not set up a full provincial government in Thrace. Instead, they controlled the area with a few forts. The largest were Doriskos and Eion. This meant most of Thrace was not affected by the Persian presence. After Persia's failed invasion of Greece in 480-79 BC, their power in Europe collapsed. By 450 BC, Persia had completely lost its control over Thrace.

The Odrysian Kingdom Begins

Early Years and Growth (around 480–431 BC)

Even though Persian rule was short, it probably helped trade and led to the first states forming among the Thracians. Thracian coins started to be made around 500 BC. This might show that early tribal kingdoms were forming. The Odrysian kingdom likely began around this time.

The first known Odrysian king was Teres I. He was a leader who wanted to expand his territory. The historian Thucydides wrote that Teres was the first strong king of the Odrysae. He said Teres was the first to create the large Odrysian empire. Teres expanded his kingdom over a large part of Thrace. However, many Thracian tribes remained independent.

Teres likely gained control of central Thrace soon after 480 BC. He built his kingdom on a strong group of warrior nobles. He and his son Sitalces expanded the kingdom from the Danube river in the north to the Aegean Sea in the south. They also expanded into eastern Thrace. Teres made his kingdom stronger in the northeast by becoming allies with the Kingdom of Scythia. The Scythian king Ariapeithes married Teres' daughter. The Odrysians were the first to go beyond the tribal system and create a large state in the eastern Balkans.

Important Burials and Treasures

Archaeological finds show that by the mid-5th century BC, a new and powerful group of nobles had emerged. They gathered many valuable items from both local and nearby regions. Burial customs changed after the Persians left. A new type of noble burial appeared in central Thrace. These were tombs built with cut stones, sometimes with stone coffins.

The earliest of these new noble tombs are found in the Duvanli burial ground. The oldest tombs date to the mid-5th century. The items found inside are very special. They included "splendid sets of head and body ornaments." Most Thracian noble tombs were for warriors. They contained weapons and gold chest plates. Two burials from Svetitsa (late 5th century BC) and Dalakova (early 4th century BC) also had beautiful gold funeral masks.

The Odrysians and the Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC)

Sitalces and His Alliance with Athens

Teres, who lived to be 92, died by the start of the Peloponnesian War in 431 BC. His son Sitalces took over. We know most about his rule from the historian Thucydides. Before the war, Sitalces fought against the Paeonians in the west. He brought some tribes under his control. His influence spread over much of Bulgaria, Greek and Turkish Thrace, and parts of southeastern Romania.

According to Thucydides, the Odrysian state was "very powerful." It had more wealth and prosperity than any other nation in Europe between the Ionian Sea and the Black Sea. In the south, much of coastal Thrace was controlled by Athens. This made Athens a direct neighbor of the Odrysians. In 431 BC, Athens made an alliance with Sitalces against Perdiccas II of Macedon. This alliance was made stronger when Sitalces married the sister of the Athenian ambassador. Sitalces' son, Sadokos, was even made an Athenian citizen.

Sitalces proved his loyalty to Athens. He arrested a Peloponnesian group trying to convince him to join Sparta. He handed them over to Athens. In 428 BC, Sitalces gathered a huge army from many different groups. He marched against Macedon. His army included various Thracians, Getae, and some Paeonians.

Sitalces managed to control some Thracian tribes. However, his invasion of eastern Macedon was not very successful. His enemies avoided open battles and hid behind their city walls. The Odrysian army could not storm these walls. Winter was coming, and food was running out. Also, the Athenian help they were promised never arrived. After failed talks, Sitalces went home. The Odrysian invasion ended after only 30 days.

Seuthes I Takes Over

Sitalces died in 424 BC while fighting the Triballi tribe. His nephew Seuthes I became king. During his rule, the Odrysians did not get involved in the coastal areas of Thrace. These areas were being fought over by Athens and Sparta. Athens started using Thracian mercenaries, called peltasts, who were light infantry. They were very successful. Eventually, Athens lost the Peloponnesian War. For a few years, they lost much of their influence in the northern Aegean Sea. Seuthes I was later replaced by Amadocus I, also known as Medokos, around 410 or 405 BC.

Challenges and a Brief Comeback

Civil Wars and Division (404–360 BC)

By the start of the 4th century BC, the Odrysian kingdom began to break apart. Two rulers were known around 405 BC: Amadocus I and Seuthes II. The historian Diodorus Siculus even called them both "kings of the Thracians." However, Seuthes II likely still saw Amadocus I as his main ruler. Amadocus was the son of the previous king, Seuthes I. Seuthes II was related to King Teres.

Seuthes II was first raised at Amadocus's court. He was sent to eastern Thrace. By 405 BC, he had gained control over a region stretching from Apollonia Pontica to parts of the northern Propontis coast. In 400 BC, he hired Greek soldiers under Xenophon. He wanted to expand his rule and force other rebels to recognize Amadocus's authority. However, he ran out of money, and the soldiers left after two months. Seuthes II eventually rebelled against Amadocus.

In 389 BC, an Athenian general helped make peace between them. Seuthes II agreed to recognize Amadocus's authority again. Amadocus died soon after 389 BC. Hebryzelmis became his successor. Hebryzelmis, like Amadocus, wanted to stay on good terms with Athens. Seuthes II, however, allied with Sparta. An Athenian record from 386/5 BC shows that Hebryzelmis sent a group to Athens. He wanted to make his rule legitimate or gain an ally against Seuthes. But Athens did not want another war in the region.

Meanwhile, Seuthes had rebelled again. This second war went badly for him. He seemed to lose all his lands. But he won them back thanks to a mercenary army led by Iphicrates. Iphicrates later married the daughter of Seuthes' son, Cotys I.

Cotys I's Strong Rule

Cotys I became king in 383 BC. The historian Michael Zahrnt described Cotys as "the right man to strengthen the run-down Odrysian realm, vigorous, and an artful diplomat." Indeed, under Cotys, the kingdom became very powerful. It was an important player in the new Hellenistic world. He and his son-in-law Iphicrates managed to conquer the lands of the deceased Hebryzelmis. This united the Odrysian kingdom under his rule. In 375 BC, he faced an invasion from the Triballi. They destroyed the western parts of his kingdom.

Cotys then focused on the important Chersonese peninsula and the Hellespont. This challenged Athens' control of the area. The Hellespont was very important for Athens' grain supply. An early invasion in 367 BC failed. But in 363/2 BC, Cotys was more successful. He defeated several Athenian generals. This brought the Chersonese and Hellespont under direct Odrysian rule. However, this success did not last long. To Athens' relief, Cotys I was murdered in 360/59 BC.

The Kingdom Falls Apart

Three Kings and Philip II's Rise (360–340 BC)

The death of Cotys, around the same time Philip II became king of Macedon, marked the start of the Odrysian kingdom's decline. The Odrysian state was split among three kings who competed with each other:

- Cersebleptes, Cotys' son, ruled the eastern parts.

- Amadocus II, possibly a son of Amadocus I, ruled central Thrace.

- Berisades controlled the western part.

Cersebleptes was the most ambitious. He continued his father's war against Athens for the Chersonese. He also tried to reunite the Odrysian kingdom. But his efforts failed. Amadocus II and Berisades, with support from Athens, resisted his attacks. In 357 BC, he was forced to accept a peace treaty. This treaty confirmed the division of the Odrysian state. Cersebleptes soon broke the treaty and continued his war.

Philip II Conquers Thrace

As early as 359 BC, Philip II of Macedon contacted a "Thracian king." He wanted to stop him from helping a Macedonian who claimed the throne. This king was likely Berisades. A year later, Philip united Macedon. He also brought the Paeonians under his control. In these early years, he did not worry much about Thrace. He saw the fighting Odrysian kingdoms as no threat.

Philip's first move into the kingdom of Berisades happened in 357/6 BC. He conquered Amphipolis and Crenides. Crenides was turned into a garrison town called Philippi. This town would be a base for future invasions. Berisades allied with the kings of Paeonia and Illyria. But Philip II defeated them one by one. Berisades was allowed to keep his kingdom for a few more years.

Cersebleptes continued trying to unite the Odrysian kingdoms. In 353/4 BC, he and Philip discussed invading Amadocus II's kingdom. Around a year later, Cersebleptes marched against Cetriporis's kingdom. Meanwhile, Athens feared an alliance between Philip and Cersebleptes. They decided to make an example by conquering the town of Sestos and destroying its people. Cersebleptes was scared. He gave up his claims on much of the Chersonese and allied with Athens.

This was not acceptable to Philip. He allied with Amadocus II and marched against Cersebleptes. After surrounding him in his home in Heraion Teichos in 351 BC, Philip forced the Thracian king to surrender. He took Cersebleptes' son as a hostage. Around this time, Philip also ended Cetriporis's kingdom. He replaced Amadocus II with Teres II.

The Thracian border remained peaceful until 347 or early 346 BC. Then, the Athenians tried again to strengthen their presence in Thrace. They probably did this at Cersebleptes' request. Macedon drove out the Athenian soldiers and defeated the Odrysians. This stopped another Thracian-Athenian alliance against Philip. As a result, Philip also put the Aegean coast under direct Macedonian control.

A few years later, Cersebleptes allied with Teres II. They invaded the Chersonese, which was now under Macedon's protection. Philip asked the Persian king Artaxerxes III to stop supporting the Ionian towns that helped Cersebleptes. Finally, Philip felt confident enough to start his biggest project yet: conquering inland Thrace. This large campaign lasted from 342 to 340 BC.

Few details are known about this campaign. It seems to have started in May or June. Philip's army moved into the interior along the Maritsa river. The Odrysians fought bravely and met the Macedonians in many battles. Philip faced some difficulties and even lost at least one battle. By the spring of 341 BC, fighting was still intense. Philip had to call for more soldiers. Although details are missing, he eventually improved his situation. He defeated Cersebleptes and Teres sometime between late 341 and early 340 BC.

The Rise of the Getic Kingdom

The Getae were a northern Thracian people. They lived between the Haemus mountains and the lower Danube river. They had been part of the Odrysian kingdom since Teres I. However, it's not clear how closely they were connected to the state. We don't know exactly when or how the Getae became independent. Perhaps it happened during Cotys I's rule or after his death in 360 BC. Rich funeral treasures from the second half of the 4th century, like those from Agighiol or Borovo, show the growing wealth of the Getic nobles.

By the mid-4th century BC, a Getic kingdom existed. It thrived for about a century. The Getic capital was Helis, which is believed to be the archaeological site of Sboryanovo. This city was founded in the 330s or early 320s BC. It had about 10,000 people. The first Getic king mentioned in historical records was Cothelas. He married his daughter Meda to Philip II. This created an alliance between their two states. The Getic kingdom survived two wars and a Celtic invasion around 280 BC. But it eventually broke apart a few decades later. Helis/Sboryanovo was completely destroyed by an earthquake in the mid-3rd century BC.

Odrysian Revival and Decline

Seuthes III's Rebellion (around 330–mid-3rd Century BC)

Philip II's conquest of the Odrysian kingdoms doubled the size of his empire. However, inland Thrace was not made a Macedonian province. Instead, it was loosely controlled by a Macedonian general. Local Thracian rulers who were trusted were allowed to govern for Macedon. They had to pay taxes and provide soldiers. These soldiers, often called "Thracians" or "Odrysians," fought in the Macedonian conquest of Persia under Philip's son, Alexander the Great. Philip founded several towns in Thrace to help with Macedonian rule, such as Cabyle and Philippopolis.

Seuthes III and the Odrysian Comeback

When Alexander the Great was away in Asia, the Macedonian generals in Thrace rebelled. They also led failed attacks against the Getae. This caused a lot of trouble in the country. In the late 330s or mid-320s BC, a man named Seuthes, later known as Seuthes III, started a Thracian rebellion. He seems to have been an Odrysian and may have been connected to the royal family.

After Alexander's death in 323 BC, one of his bodyguards, Lysimachus, was made governor of Thrace. Soon after he arrived, he faced Seuthes. Seuthes had gathered many Thracians to his side. Seuthes wanted to bring back an independent Odrysian state. A battle happened between Seuthes and Lysimachus. Lysimachus won, but not by much. Both sides prepared for another fight.

Eventually, they reached an agreement. Seuthes would control the inland areas, and Lysimachus would control the coastal regions. There is no evidence that Lysimachus made Seuthes his vassal. Thrace north of the Rhodopes mountains likely remained outside Lysimachus's control. In 313 BC, Seuthes allied with Greek towns on the Black Sea coast that were rebelling. But Lysimachus defeated this alliance. It's possible that Seuthes married Lysimachus's daughter, Berenice, to ensure peace. After this, there's no record of them fighting again.

Seuthes wanted to create a Hellenistic kingdom. However, he did not call himself "king" on his coins. Probably after Alexander's death in 323 BC, Seuthes founded a town on the Tonzos river, near modern Kazanlak. He named it Seuthopolis after himself. The town was built like Macedonian cities of the time and showed strong Greek influences. Seuthopolis likely served as the capital of Seuthes' kingdom.

The Fall of Seuthopolis

We don't know exactly when Seuthes III died. Estimates range from the late 4th century to the 280s BC. Coins made in his name include some that were stamped over coins of other kings. This suggests his coins were made until the early 3rd century BC. Seuthes was symbolically buried in the Golyama Kosmatka burial mound, but his actual body was not there. He might have been killed in battle.

A long inscription from Seuthopolis shows that the town faced problems. It mentions Seuthes' wife, Berenice, and their four sons. The document was issued in Berenice's name. It says "when Seuthes was in good health," which means he was either dead or dying when it was written. Berenice had taken over the rule. The inscription describes talks between Berenice and Spartokos, the ruler of Cabyle. Cabyle had become an important city-state.

The end of Seuthopolis is debated. But it's clear the town was destroyed in the first half of the 3rd century BC. Some scholars believe the Celts conquered it in the 270s BC. The Celts were causing destruction across the Balkan Peninsula. They also attacked Thrace many times. Around 278 BC, they founded a kingdom in eastern Thrace.

A newer idea suggests Seuthopolis was destroyed in the 250s BC. This is based on new dating of pottery and coins. It also notes the presence of Celtic items. The archaeological evidence also shows that siege weapons were used. This makes it less likely that Celts destroyed it. It might have been destroyed by the Seleucid king Antiochus II. He campaigned in inland Thrace around 252 BC.

The Odrysians After 250 BC

Most modern historians believe the Odrysian kingdom continued to exist. They think it lasted through the Hellenistic period and into the early Roman Empire. It then became a Roman vassal state. However, there is very little evidence for this. After the mid-3rd century BC, Thrace was split into many different political groups. In the interior, various Thracian rulers were in charge. In the east was the kingdom of Tylis, a Celtic state that relied on demanding tribute. It was eventually destroyed by a Thracian revolt after 220 BC.

In the last years of the 3rd century BC, Macedon, under king Philip V, began to expand again. He took advantage of the Ptolemies' weakness. Philip also led a campaign into inland Thrace. He temporarily lost his Thracian lands after the Second Macedonian War in 197 BC. But he reconquered most of them a decade later. In 184 or 183 BC, he pushed into the plains of the upper Hebros river. He defeated the Odrysians and other local tribes. He conquered Philippopolis, but the Odrysians soon took it back. It's worth noting that no Odrysian king is mentioned during these events.

Between 171 and 168 BC, Philip's heir Perseus fought the Roman Republic in the Third Macedonian War. Perseus's most trusted ally was the Thracian king Cotys. The historian Polybius calls him an Odrysian. He fought in important battles. But he eventually became a Roman ally after the war. His identity is uncertain. It is a fact, however, that Cotys was the last king in historical records to be clearly called an "Odrysian." There is also no evidence that Odrysians were connected to the royal families of the Sapaeans and Asti in the 1st century BC.

By the mid-1st century BC, the Romans controlled coastal Thrace. The most important Thracian tribes were the Sapaeans and the Asti. The Romans decided not to directly govern inland Thrace. Instead, they relied on a large, Greek-influenced client kingdom. This kingdom was similar to the old Odrysian kingdom. After the Battle of Actium in 31 BC, the Romans likely ended the Asti dynasty. They established the Sapaeans in Bizye, the former Asti capital. The Sapaeans of Bizye created a large kingdom loyal to Rome. They even expanded into the interior.

In 21 AD, king Rhoemetalces II sought safety in Philippopolis. He was facing a rebellion, which included Odrysians. The historian Tacitus described the Odrysians as powerful. However, their uprising failed because they were not well organized. The Romans eventually ended the Sapaean kingdom in 45/6 AD. They turned it into the province of Thracia.

How Odrysian Kings Ruled

Even though the Odrysian kingdom covered a large area, it probably did not have formal state systems before Seuthes III's rule. The Odrysian kingship was much like the Persian court. It also had many similarities to how kings ruled in Macedon. Unlike in Greek city-states, Odrysian kings had to prove their right to rule through military skill, religion, and giving gifts.

Giving and receiving gifts was very important for a king's power. This practice came from the Persian court. The king received valuable gifts like gold, silver, and horses. In return, he was expected to give gifts like items, women, or land. This helped him gain loyalty and expand his military. Such systems were often unstable. A king's power could change easily.

We don't know much about the royal court and how the kingdom was run. This is because many historical records are missing. We can assume that, like in early Macedon, the Odrysian kings were at the center of the kingdom. They controlled policies, made coins, appointed loyal helpers, and led armies. The kingdom was essentially the king's personal property.

Below the king was a group of noble horse warriors and administrators. These came from the royal court and from other tribes. The historian Thucydides called these local rulers paradynasteuontes, meaning "those who share power." The Odrysian kingdom seems to have been quite decentralized. It had many different local noble groups competing for power. Their rule over their people, who lived in small villages, was very loose. It was mainly done through raids and demanding tribute.

There is no evidence that the early Odrysian kings had a fixed capital city. Instead, they probably moved around the kingdom. They stayed in fortified homes. These small fortified places were called thyrseis by the Greeks. They were the strongholds of the Thracian nobles. This changed somewhat in the late 4th century BC. Seuthes III founded Seuthopolis. This marked the start of early state-like systems, likely inspired by Hellenistic Macedon. Seuthopolis remained quite small, with no more than 1,000 people. It was probably home to the kingdom's nobles. The common people continued to live outside the city walls. They still practiced the old farming and herding way of life.

Odrysian Army and Warfare

When Sitalces' army invaded Macedon, it was said to have 150,000 men. This number is probably too high. About 100 years later, when Seuthes III faced Lysimachus, his army had shrunk to 28,000 men. A large part of these armies were horsemen. In Sitalces' army, one out of every three warriors was a horseman. These came from the Odrysians and the Getae. Seuthes III's army had 8,000 riders, likely all Odrysians. Most of Sitalces' foot soldiers were not very well organized. It seems that fighting was mainly for the nobles. Military training for common people was not considered suitable.

Despite this, the Thracian foot soldiers made a great impression on the Greeks. The Greeks hired them as mercenaries. Meanwhile, the Odrysian kings used Greek mercenary commanders like Xenophon. Greek towns within Thrace were defended by the colonists themselves.

Initially, the Odrysian army had light infantry and light cavalry. The infantry used bows, slings, spears, swords, axes, and light crescent-shaped shields called pelte. These warriors were called "peltasts." Round and oval shields were also used. A weapon found mostly in the western and central Rhodopes was the Rhomphaia. The cavalry used the same weapons as the infantry, except for slings.

In the later 5th century BC, Thracian cavalry started to wear armor. They used helmets of different types, with the Chalcidian type being the most popular. The earliest body armor was a simple type of muscle cuirass. Leather and linen armor were also worn. In the 4th century BC, scale armour became popular. Greaves (leg armor) were also adopted then. There is also evidence that the Thracians used siege weapons, especially catapults.

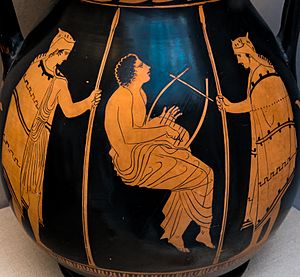

Culture and Art

Odrysian crafts and metalwork were greatly influenced by the Persian Empire. Thracians, like Dacians and Illyrians, often decorated themselves with tattoos. Thracian warfare was also influenced by the Celts. The Triballi tribe had adopted Celtic equipment.

Thracian clothing was known for its quality. It was made from hemp, flax, or wool. Their clothes were similar to those of the Scythians. This included jackets with colored edges and pointed shoes. The Getai tribe was so similar to the Scythians that they were often confused. Nobles and some soldiers wore caps.

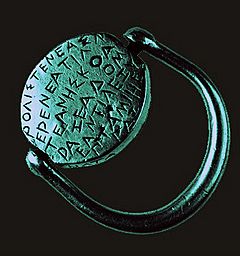

There was a lot of cultural exchange between the Greeks and Thracians. Greek customs and styles helped change society in the eastern Balkans. Among the nobles, Greek fashion in clothing, jewelry, and military gear was popular. Unlike the Greeks, Thracians often wore trousers. Thracian kings were influenced by Hellenization. The Greek language was spoken by at least some members of the royal family in the 5th century BC. It became the language used by administrators. The Greek alphabet was adopted as the new script for the Thracian language.

Archaeology Discoveries

Archaeologists have found residences and temples of the Odrysian kingdom. Many are around Starosel in the Sredna Gora mountains. They uncovered the northeastern wall of the Thracian kings' residence. It is 13 meters long and preserved up to 2 meters high. They also found the names of Cleobulus and Anaxandros. These were generals of Philip II of Macedon who led the attack on the Odrysian kingdom.

List of Odrysian Kings

The list below includes the known Odrysian kings of Thrace. However, much of it is based on guesses. This is because sources are incomplete, and new discoveries are always being interpreted. Other Thracian kings (some possibly not Odrysian) are also included. Odrysian kings, though called Kings of Thrace, never ruled all of Thrace. Their control changed based on tribal relationships. Odrysian kings (names are in Greek or Latin forms):

- Teres I, son of ? Odryses, (480/450–430 BC)

- Sparatocus, son of Teres I (c. 465?-by 431 BC)

- Sitalces, son of Teres I (by 431–424 BC)

- Seuthes I, son of Sparatocus (424–396 BC)

- Maesades, father of Seuthes II, local ruler in eastern Thrace

- Teres II, local ruler in eastern Thrace

- Metocus (= ? Amadocus I), son of ? Sitalces

- Amadocus I, son of ? Metocus (unless identical to him) or of Sitalces (410–390 BC)

- Seuthes II, son of Maesades, descendant of Teres I, king in southern districts (405–391 BC)

- Hebryzelmis, son or brother of ? Seuthes I (390–384 BC)

- Cotys I, son of ? Seuthes I or Seuthes II (384–359 BC)

- Cersobleptes, son of Cotys I, king in eastern Thrace (359-341 BC)

- Berisades, rival of Cersobleptes, king in western Thrace in Strimos (359–352 BC)

- Amadocus II, rival of Cersobleptes, king in central Thrace in Chersonese & Maroneia (359–351 BC)

- Cetriporis, son of Berisades, king in western Thrace in Strimos (358–347 BC)

- Teres III, son of ? Amadocus II, king in central Thrace in Chersonese & Maroneia (351–342 BC)

- Seuthes III, rebel against Macedonian rule (by 324–after 312)

- Roigos, son of Seuthes (III?) (early 3rd century BC ?)

- The survival of a specifically "Odrysian" state beyond the early 3rd century BC is considered debatable.

- Cotys IV, son of Seuthes V (by 171-after 166 BC), last king described explicitly as Odrysian in the sources.

Odrysian Treasures

Literature

- M. Tacheva, The Kings of Ancient Thrace. Book One, Sofia, 2006.

- S. Topalov, The Odrysian Kingdom from the Late 5th to the Mid-4th C. B.C., Sofia, 1994.

See also

In Spanish: Reino odrisio para niños

In Spanish: Reino odrisio para niños

| DeHart Hubbard |

| Wilma Rudolph |

| Jesse Owens |

| Jackie Joyner-Kersee |

| Major Taylor |