History of Serbia facts for kids

The history of Serbia tells the story of Serbia and the Serbian people, from ancient times to today. Serbia's borders and the areas ruled by Serbs have changed a lot over the centuries. This means Serbia's history includes many different periods and places.

Serbs arrived in the Balkans region during the 6th and 7th centuries. One of their first important states was the First Serbian Principality. It was ruled by the Vlastimirovići family and covered parts of modern-day Montenegro, Bosnia, Dalmatia, and Serbia. By the 11th century, it grew into a larger state called a Grand Principality. In 1217, the Kingdom of Serbia was formed, and the national church (Serbian Orthodox Church) was also established. This was under the Nemanjić family. In 1345, the Serbian Empire was created, which covered most of the Balkan peninsula. However, by 1540, Serbia became part of the Ottoman Empire.

Many Serbs moved north to the Kingdom of Hungary. This area later became known as Serbian Vojvodina. A major event was the Serbian revolution against Ottoman rule in 1817. This led to the creation of the Principality of Serbia. It became truly independent in 1867 and was fully recognized by other powerful countries at the Berlin Congress of 1878. After winning the Balkan Wars in 1912–1913, Serbia gained new territories like Vardar Macedonia, Kosovo, Metohija, and Raška.

In late 1918, after the Austro-Hungarian Empire was defeated, Serbia expanded to include parts of the former Serbian Vojvodina. Serbia then joined with other Slavic regions that were once part of Austria-Hungary to form the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs. On December 1, 1918, the Kingdom of Serbia officially joined this union, and the country was named the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes.

Serbia got its current borders after World War II. It became a part of the Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia, which was formed in November 1945. After Yugoslavia broke up in the 1990s, following a series of wars, Serbia became an independent country again on June 5, 2006. This happened after a short-lived union with Montenegro ended.

Contents

- Ancient Times in Serbia

- Serbia Under Roman Rule

- Medieval Serbian States

- Early Modern Serbian History

- Modern Serbian History

- Serbian Revolution and Self-Governing Principality (1804–1878)

- Principality and Kingdom of Serbia (1878–1918)

- Serbia in World War I (1914–1918)

- Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes / Kingdom of Yugoslavia (1918–1941)

- Serbia in World War II (1941–1944)

- Serbia as a Federal Unit in Socialist Yugoslavia (1945–1992)

- Serbia and Montenegro (1992–2006)

- Republic of Serbia (2006–Present)

- See also

Ancient Times in Serbia

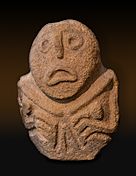

Right: A figure from the Vinča culture, around 4000–4500 BC.

Ancient tribes in the Balkans formed between 2000 and 1000 BC. The northernmost city of the Ancient Macedonians was in southern Serbia. The Celtic Scordisci tribe took over most of Serbia in 279 BC. They built many forts across the region.

The Roman Empire conquered this area between the 2nd century BC and the 1st century AD. The Romans developed cities like Singidunum (modern Belgrade), Sirmium (Sremska Mitrovica), and Naissus (Niš). You can still see some Roman remains today, like Trajan's Bridge and Felix Romuliana (a UNESCO site).

The ancient Neolithic Starčevo and Vinča cultures were located near Belgrade. They were important in the Balkans about 8,500 years ago. Some experts believe that the symbols from the Vinča culture might be one of the earliest forms of writing systems.

Serbia's location between two continents meant it was often invaded. The Thracians lived in Serbia before the Illyrian tribes moved into the southwest. Greeks settled in the south in the 4th century BC. The town of Kale was the northernmost point of Alexander the Great's empire.

Serbia Under Roman Rule

Right: Gamzigrad, a palace built by Emperor Galerius.

The Romans conquered parts of what is now Serbia in the 2nd century BC. They established the province of Illyricum. The rest of central Serbia was conquered by 75 BC, becoming the province of Moesia. Srem was taken by 9 BC, and Bačka and Banat by 106 AD.

Today's Serbia includes parts of the ancient Roman regions of Moesia, Pannonia, Dalmatia, Dacia, and Macedonia. The city of Sirmium (Sremska Mitrovica) in northern Serbia was one of the four most important cities of the late Roman Empire. It even served as the capital during the Tetrarchy period.

Seventeen Roman Emperors were born in the area that is now Serbia. Belgrade is said to have been part of 140 wars since Roman times.

By the early 6th century, South Slavs had moved into the Byzantine Empire. They mixed with the local people, like the Celts, Dacians, and Illyrians. This mixing formed the basis of the modern Serbian people.

Medieval Serbian States

Serbs lived in "Slav lands" within the Byzantine world. These lands were initially independent from Byzantine control. The Vlastimirović dynasty created the Serbian Principality in the 7th century. By 822, Frankish writers noted that Serbs held a large part of Dalmatia.

Serbs gradually became Christian, a process that started in the 7th century and finished by the mid-9th century. In the mid-10th century, the Serbian state stretched from the Adriatic Sea to the Sava and Morava rivers.

In 924, Serbs defeated a small Bulgarian army. This led to a bigger attack by Bulgaria, which took over Serbia that year. Later, in 997, the Bulgarian tsar Samuel defeated and captured Prince Jovan Vladimir of Duklja, taking control of Serb lands again. The Serbian state then broke apart. The Byzantines ruled the region for a century.

In 1040, Serbs in Duklja, a coastal region, revolted under the leadership of the Vojislavljević dynasty. In 1091, the Vukanović dynasty established the Serbian Grand Principality in Raška.

In 1166, Stefan Nemanja became ruler, starting a time of growth for Serbia under the Nemanjić dynasty. Nemanja's son, Rastko (later Saint Sava), helped the Serbian Church become independent in 1219. He also wrote the oldest known constitution. At the same time, Stefan the First-Crowned established the Serbian Kingdom in 1217.

Medieval Serbia was strongest during the rule of Stefan Dušan (1331–1355). He used the Byzantine civil war to expand his state. He conquered territories to the south and east, reaching as far as the Peloponnese. He was crowned Emperor of Serbs and Greeks in 1346.

The Battle of Kosovo in 1389 against the rising Ottoman Empire was a turning point. It is seen as the beginning of the fall of the medieval Serbian state. The noble families of Lazarević and Branković then ruled the Serbian Despotate in the 15th and 16th centuries. After Constantinople fell to the Ottomans in 1453, and the Siege of Belgrade failed, the Serbian Despotate finally fell in 1459 after the siege of its temporary capital, Smederevo. By 1455, central Serbia was fully conquered by the Ottoman Empire. Belgrade fell in 1521, opening the way for Ottoman expansion into Central Europe.

Early Modern Serbian History

From the time Serbia was conquered by the Ottomans in the late 15th century until the start of the Serbian Revolution in 1804, many wars were fought on Serbian land. These were mainly between the Habsburg (Austrian) and Ottoman Empires. During this period, different parts of Serbia were ruled by either the Ottomans or the Habsburgs.

Ottoman Rule in Serbia

The medieval states of Bosnia, Herzegovina, and Zeta lasted until the late 1400s. A Serbian principality was briefly brought back by the Branković dynasty in what is now Vojvodina. It was ruled by Serbian leaders who had been forced to leave their homes. This state existed until 1540 as a Hungarian vassal, before falling to the Ottomans.

Many Serbs were taken into the Ottoman system called devshirme. This was a form of forced recruitment where Christian boys from the Balkans were made to convert to Islam. They were then trained to become soldiers in the Ottoman army, known as the Janissaries.

From the 14th century onwards, more and more Serbs moved north to the region now called Vojvodina. This area was then under the rule of the Kingdom of Hungary. Hungarian kings encouraged Serbs to move there and hired many of them as soldiers. During the conflicts between the Ottoman Empire and Hungary, these Serbs tried to restore a Serbian state.

After the Battle of Mohács in 1526, where the Ottomans defeated the Hungarian army, a Serbian mercenary leader named Jovan Nenad took control of what is now Vojvodina. He created a short-lived independent state with Subotica as its capital. However, King John of Hungary defeated Jovan Nenad in 1527.

European powers, especially Austria, fought many wars against the Ottoman Empire. Sometimes, Serbs helped Austria. During the Austrian–Ottoman War (1593–1606), some Serbs took part in an uprising in Banat in 1594. The Ottoman Sultan Murad III punished them by burning the relics of St. Sava. When Austria made peace with the Ottomans, they left the Serbs to face Ottoman revenge. This pattern happened many times over the centuries.

During the Great War (1683–90) between the Ottoman Empire and the Holy League (Austria, Poland, and Venice), these powers encouraged Serbs to rebel against the Ottomans. Uprisings spread across the western Balkans. But when the Austrians left the Ottoman region, they invited Serbs loyal to Austria to move north into Hungarian lands. Many Serbs, led by patriarch Arsenije Čarnojević, left their homes to avoid Ottoman punishment and moved north.

Another important event happened in 1716–18. The area from Dalmatia to Belgrade became a battlefield in a new war between Austria and the Ottomans. Some Serbs again sided with Austria. After a peace treaty was signed in Požarevac, the Ottomans lost many areas, including northern Serbia.

The last Austrian-Ottoman war was from 1788–91. Austria again urged Christians in Bosnia and Serbia to rebel. No more wars were fought between them until the 20th century, which saw the fall of both the Austrian and Ottoman empires after World War I.

Modern Serbian History

Serbian Revolution and Self-Governing Principality (1804–1878)

Serbia gained its self-rule from the Ottoman Empire through two uprisings. The First Serbian Uprising in 1804 was led by Đorđe Petrović (Karađorđe). The Second Serbian Uprising in 1815 was led by Miloš Obrenović. Even though Serbia gained self-rule, Turkish troops remained in the capital, Belgrade, until 1867. In 1817, the Principality of Serbia was given de facto (in practice) independence from the Ottoman Empire.

This period saw Serbia not just have a national revolution but also a social one. Serbia started to modernize. It gained freedom from foreign rule, peasants got land, Belgrade became the main political and cultural center, and modern European ways of life and economy were adopted. However, there were also long delays, continued poverty, and a growing gap between the modern city people and the traditional farmers.

Principality and Kingdom of Serbia (1878–1918)

The self-governing Principality became an internationally recognized independent country after the Russo-Turkish War in 1878. Serbia remained a principality until 1882, when it became a Kingdom. During this time, politics mainly focused on the rivalry between the Obrenović and Karađorđević royal families.

This period was marked by progress in Serbia's economy, culture, and arts. This was largely because the government wisely sent young people to European cities for education. They brought back new ideas and values. In 1882, Serbia was officially declared the Kingdom of Serbia.

During the Revolutions of 1848, Serbs in the Austrian Empire declared their own self-governing province called Serbian Vojvodina. In 1849, the Austrian emperor changed this province into an Austrian crown land. This was called the Voivodeship of Serbia and Temes Banat. Against the wishes of the Serbs, the province was ended in 1860. However, Serbs from the region got another chance to achieve their political goals in 1918. Today, this region is known as Vojvodina.

In 1885, Serbia protested against Bulgaria uniting with Eastern Rumelia and attacked Bulgaria. This was the Serbo-Bulgarian War. Despite having better weapons, Serbia lost the war.

In the second half of the 19th century, Serbia became the Kingdom of Serbia. It joined the group of European states, and the first political parties were formed, bringing new energy to political life. The May Coup in 1903 brought Karađorđe's grandson, King Peter I, to the throne. This opened the way for parliamentary democracy in Serbia. King Peter, who had a European education, translated "On Liberty" by John Stuart Mill and gave his country a democratic constitution. This started a period of parliamentary government and political freedom, which was later interrupted by wars.

Serbia had several national goals. Many Serbs living in Bosnia looked to Serbia as the center of their national identity. However, they were ruled by the Austrian Empire. Austria's takeover of Bosnia in 1908 greatly angered the Serbian people. Some people plotted revenge, which they carried out in 1914 by assassinating the Austrian heir. Serbian thinkers dreamed of a South Slavic state, which became Yugoslavia in the 1920s.

Serbia was landlocked, meaning it had no access to the sea. It strongly wanted access to the Mediterranean, ideally through the Adriatic Sea. Austria worked hard to block Serbia's access to the sea. For example, it helped create Albania in 1912. Montenegro, Serbia's only true ally, had a small port. But Austrian territory blocked access until Serbia gained Novi Pazar and part of Macedonia from Turkey in 1913. To the south, Bulgaria blocked Serbia's access to the Aegean Sea.

Serbia, Greece, Montenegro, and Bulgaria formed the Balkan League. They went to war with the Ottomans in 1912–13. They won a clear victory and drove the Ottoman Empire out of almost all the Balkans. The main remaining enemy was Austria, which strongly opposed Pan-Slavism (the idea of uniting all Slavic peoples) and Serbian nationalism. Austria was ready to go to war to stop these threats. The growth of ethnic nationalism would eventually lead to the downfall of the multicultural Austro-Hungarian Empire. Serbia's expansion would also block Austrian and German plans for direct rail links to Constantinople and the Middle East. Serbia relied mainly on Russia for support from a major power. Russia was at first hesitant to support Pan-Slavism but changed its mind in 1914 and promised military support to Serbia.

Serbia in World War I (1914–1918)

Despite its small size and population of 4.6 million, Serbia had a very effective army mobilization during the war. It had a highly skilled officer corps. Serbia called 350,000 men to arms, with 185,000 in combat units. However, the Balkan Wars had used up many of Serbia's soldiers and supplies, making it dependent on France for help. Austria invaded Serbia twice in 1914 but was pushed back.

On June 28, 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the heir to the Austrian throne, was assassinated in Sarajevo, the capital of Bosnia. He was killed by Gavrilo Princip, a member of a group called Young Bosnia. This event was used as a reason for Austria to declare war on Serbia on July 28, 1914, starting World War I. This happened even though Serbia had accepted almost all of Austria-Hungary's demands three days earlier. The Austro-Hungarian army invaded Serbia and captured Belgrade on December 2, 1914. However, the Serbian Army successfully defended the country, won several battles, and recaptured Belgrade on December 15, 1914.

In late 1915, German generals took control and invaded Serbia with Austrian and Bulgarian forces. The Serbian army retreated across the Albanian mountains to the Adriatic Sea by January 1916. Only 70,000 soldiers made it through. They were then evacuated to Greece by Italian, French, and British naval forces.

Serbia became an occupied land. Diseases were common, but the Austrians paid well for food, so conditions were not extremely harsh. Austria tried to remove politics from Serbia, reduce violence, and bring the country into its empire. However, the harsh military occupation and Austrian military actions in Serbia worked against these goals. Serbian nationalism remained strong, and many young men secretly left to help rebuild the Serbian army in exile.

The Triple Entente (Allied powers) promised Serbia territories like Srem, Bačka, Baranja, eastern Slavonia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and eastern Dalmatia as a reward after the war. After recovering on Corfu, the Serbian Army returned to fight on the Thessaloniki front with other Allied forces. Serbia suffered 1,264,000 casualties, which was 28% of its population of 4.6 million. This also meant 58% of its male population was lost. Serbia never fully recovered from these losses and had the highest casualty rate in World War I.

Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes / Kingdom of Yugoslavia (1918–1941)

Right: Mihajlo Pupin, a physicist, influenced the borders of Yugoslavia after World War I.

A successful Allied attack in September 1918 led to Bulgaria's surrender. Then, the occupied Serbian territories were freed in November 1918. On November 25, the Assembly of Serbs, Bunjevci, and other groups in Vojvodina voted to join Serbia. Also, on November 29, the National Assembly of Montenegro voted to unite with Serbia. Two days later, leaders from Austria-Hungary's southern Slavic regions voted to join the new State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs.

With the end of World War I and the collapse of both the Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman Empires, the time was right to create the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes in December 1918. The idea of a united South Slavic state had been popular among thinkers for a long time. However, international politics had not allowed it until then. After the war, thinkers were replaced by politicians, and some influential Croatian politicians opposed the new state from the very beginning.

In the early 1920s, the Yugoslav government, led by Serbian prime minister Nikola Pašić, used police pressure and other methods to keep the opposition in the minority in parliament. Pašić believed that Yugoslavia should be very centralized. He wanted to create a "Greater Serbian" idea of power focused in Belgrade, rather than having separate regional governments.

However, a major crisis happened in 1928 when a Serb representative shot at opposition members in Parliament. Two people were killed, and the leader of the Croatian Peasants Party, Stjepan Radić, was badly wounded and later died.

King Alexander I used this crisis to ban political parties in 1929. He took over executive power and renamed the country Yugoslavia. He hoped to stop groups wanting to separate and calm nationalist feelings. But the international situation changed. In Italy and Germany, Fascists and Nazis came to power. Joseph Stalin became the absolute ruler in the Soviet Union. None of these three countries liked King Alexander I's policies. The first two wanted to change the international agreements made after World War I. The Soviets wanted to regain their influence in Europe. Yugoslavia was seen as an obstacle to these plans, and King Alexander I was the main supporter of Yugoslavia's policies.

During an official visit to France in 1934, the king was assassinated in Marseille. He was killed by a member of the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization, an extreme nationalist group from Bulgaria. This group wanted to take over territories along Yugoslavia's eastern and southern borders. They worked with the Ustaše, a Croatian fascist group that wanted to separate from Yugoslavia.

The international political scene in the late 1930s was marked by growing tension and aggressive actions by totalitarian governments. Croatian leader Vladko Maček and his party managed to get a Croatian administrative province (banovina) created in 1939. This agreement stated that Croatia would remain part of Yugoslavia. However, Croatia quickly started to build its own independent political identity in international relations.

Serbia in World War II (1941–1944)

Before World War II, Prince Regent Paul of Yugoslavia signed a treaty with Hitler. However, a popular uprising rejected this agreement, and Prince Regent Paul was sent into exile. King Peter II then took on full royal duties.

In the early 1940s, Yugoslavia was surrounded by hostile countries. All its neighbors, except Greece, had signed agreements with Germany or Italy. Adolf Hitler strongly pressured Yugoslavia to join the Axis powers. The government was ready to compromise, but the people felt very differently. Public protests against Nazism led to a harsh reaction.

On April 6, 1941, Germany, Italy, Hungary, and Bulgaria invaded Yugoslavia. The German air force (Luftwaffe) bombed Belgrade for three days, killing 17,000 people. German forces captured Belgrade on April 13, 1941. Four days later, on April 17, the Royal Yugoslavian Army surrendered. King Peter II left the country to seek Allied support. He was seen as a hero for opposing Hitler. The Royal Yugoslav Government continued to work from London.

The Axis powers then divided Yugoslavia. The western parts, including Bosnia and Herzegovina, became a Nazi puppet state called the Independent State of Croatia (NDH). It was ruled by the Ustashe. Most of modern Serbia was occupied by the German army and ruled by the German Military Administration in Serbia. This area was called Serbia or the Territory of the Military Commander in Serbia. It was also governed by Serbian puppet governments, first under Milan Aćimović and then under General Milan Nedić. The northern parts were taken by Hungary, and eastern and southern parts by Bulgaria. Kosovo and Metohija were mostly taken by Albania, which was supported by fascist Italy. Montenegro also lost land to Albania and was then occupied by Italian troops. Slovenia was divided between Germany and Italy.

In Serbia, the German occupation authorities set up several concentration camps. These camps held Jews, members of the communist Partisan resistance, and Chetniks (royalist resistance).

The largest concentration camps were Banjica and Sajmište near Belgrade. According to careful estimates, about 40,000 Jews were killed there. In all these camps, about 90 percent of the Serbian Jewish population died. In the Bačka region, which Hungary took over, many Serbs and Jews were killed in a 1942 raid by Hungarian authorities. Serbs also faced persecution in Syrmia, controlled by the Independent State of Croatia, and in Banat, under direct German control.

The harsh actions of the German occupation forces and the terrible policy of the Croatian Ustaša regime led to a strong anti-fascist resistance in the NDH. The Ustaša regime targeted Serbs, Jews, Roma, and anti-Ustaša Croats. Many Croats and other nationalities stood up against these actions and the Nazis. Many joined the Partisan forces, created by the Communist Party (National Liberation Army led by Josip Broz Tito). They fought for liberation and against the Nazis and all who opposed communism.

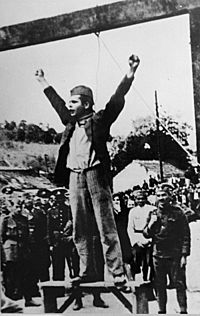

During and after this war, the Partisans killed many civilians who did not support their Communist ideas. They shot people without trials or after politically motivated courts. An example is the case of Draža Mihailović, the leader of the Chetniks. After the war, a new Agricultural Reform meant that farmers had to give most of their crops and cattle to the state, or face serious jail time. Land and property were taken on a large scale. Many people also lost their civil rights. Censorship was put in place at all levels of society and media, and a cult of Tito was created in the media.

On October 20, 1944, the Soviet Red Army liberated Belgrade. By the end of 1944, all of Serbia was free from German control. Yugoslavia had some of the greatest losses in the war. About 1,700,000 people (10.8% of the population) were killed. The national damages were estimated at US$9.1 billion at that time.

Serbia as a Federal Unit in Socialist Yugoslavia (1945–1992)

After the war, Josip Broz Tito became the first president of the new socialist Yugoslavia. He ruled through the League of Communists of Yugoslavia. Yugoslavia, once mainly a farming country, became a mid-level industrial country. It gained international respect by supporting countries becoming independent from colonial rule and by leading the Non-Aligned Movement. Socialist Yugoslavia was set up as a federal state with six republics: Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia, Montenegro, and Macedonia. It also had two autonomous regions within Serbia: Vojvodina and Kosovo.

The main ideas of Tito's Yugoslavia were "brotherhood and unity," workers' self-management, and state-owned property with very little private property. At first, the country copied the Soviet model. But after a split with the Soviet Union in 1948, it looked more towards the West. Eventually, it created its own type of socialism, with some parts of a market economy. It also received large financial loans from both the East and the West.

The 1974 constitution made the federation much less centralized. It gave more autonomy to Yugoslavia's republics and to Serbia's autonomous provinces.

When Tito died on May 4, 1980, he was replaced by a presidency that rotated yearly among the six republics and two autonomous regions. This led to a weakening of central power and the ties between the republics. During the 1980s, the republics followed very different economic policies. Slovenia and Croatia, which wanted more independence, allowed many market-based reforms. Serbia, however, stuck to its state-owned system. This caused tension between the north and south. Slovenia, in particular, saw strong economic growth. Before the war, inflation rose very high. Then, under Prime Minister Ante Markovic, things started to get better. Economic reforms had opened up the country, living standards were at their highest, and capitalism seemed to be entering the country. No one thought that the first gunshots would be fired just a year later.

Within a year of Tito's death, the first problems appeared. In the spring of 1981, protests spread from the University of Pristina to cities in Kosovo. People demanded that Kosovo become a full republic. These protests were violently stopped by the police, with many deaths, and a state of emergency was declared. Serbian worries about how Serbs were treated in other republics, especially in Kosovo, grew worse. This was made worse by the SANU Memorandum, a document from the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts published in 1986. It claimed that Serbs were suffering a genocide in Kosovo. Slobodan Milošević, leader of the League of Communists of Serbia since May 1986, became a champion for Serbian nationalists. On April 24, 1987, he visited Kosovo Polje. After local Serbs clashed with the police, he declared, "No one has the right to beat you."

Slobodan Milošević became the most powerful politician in Serbia on September 25, 1987. He defeated his former mentor, Serbian President Ivan Stambolic, during a televised meeting. Milošević ruled Serbia from his position as Chairman of the Central Committee of the League of Communists of Serbia. On May 8, 1989, he became President of Serbia. Milošević's supporters gained control of three other parts of Yugoslavia in what was called the Anti-bureaucratic revolution: Vojvodina on October 6, 1988, Kosovo on November 17, 1988, and Montenegro on January 11, 1989. On November 25, 1988, the Yugoslav National Assembly allowed Serbia to change its constitution. In March 1989, this was done, removing autonomy from Vojvodina and Kosovo, which caused great unrest in Kosovo. On June 28, 1989, Slobodan Milošević gave what became known as the Gazimestan Speech. This was the main part of a day-long event, attended by about one million Serbs, to mark 600 years since the Serbian defeat at the Battle of Kosovo by the Ottoman Empire. In this speech, Milošević mentioned the possibility of "armed battles" in Serbia's future. Many saw this as a sign of Yugoslavia's collapse and the bloodshed of the Yugoslav Wars.

On January 23, 1990, at its 14th Congress, the Communist League of Yugoslavia voted to end its monopoly on political power. But on the same day, it effectively stopped existing as a national party. The League of Communists of Slovenia walked out after Slobodan Milošević blocked all their reform proposals. On July 27, 1990, Milošević merged the League of Communists of Serbia with several smaller communist parties to form the Socialist Party of Serbia. A new Constitution was written and came into effect on September 28, 1990. It changed the one-party Socialist Republic of Serbia into a multi-party Republic of Serbia. The first multi-party elections were held on December 9 and 23, 1990. The Socialist Party of Serbia won, as Milošević kept strong control over state media, and opposition parties had little access. On March 9, 1991, a large protest in Belgrade turned into a riot with violent clashes between protesters and police. It was organized by Vuk Drašković's Serbian Renewal Movement (SPO). Two people died in the violence.

The Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia broke up in 1991–1992 through a series of wars. This followed the declarations of independence by Slovenia and Croatia on June 25, 1991, and Bosnia and Herzegovina on March 5, 1992. Macedonia left the federation peacefully on September 25, 1991. The Yugoslav People's Army(JNA) tried but failed to stop Slovenia from leaving in the Ten Day War (June 26 – July 6, 1991). It fully withdrew by October 26, 1991. The JNA also tried but failed to stop Croatia from leaving during the first part of the Croatian War of Independence (June 27, 1991 – January 1992). However, it did help the Croatian Serb minority establish the Republic of Serb Krajina, which looked to Serbia for support. The biggest battle of this war was the Siege of Vukovar. After the Bosnian War started on April 1, 1992, the JNA officially withdrew all its forces from Croatia and Bosnia in May 1992. It was formally dissolved on May 20, 1992. Its remaining forces were taken over by the new Federal Republic of Yugoslavia.

Serbia and Montenegro (1992–2006)

The two remaining republics of Yugoslavia, Serbia and Montenegro, formed a new federation on April 28, 1992, called the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia.

The Milošević Years

After the breakup of Yugoslavia, the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (FRY) was created in 1992 as a federation. In 2003, it was changed into a political union called the State Union of Serbia and Montenegro (SCG).

From March 24 to June 10, 1999, NATO carried out an air bombing campaign against the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. This followed a violent crackdown on ethnic Albanian separatists in the province of Kosovo. After the Kumanovo Agreement was signed and Yugoslav troops withdrew in June, Kosovo became a United Nations protectorate. This was under the UN Mission in Kosovo (UNMIK), based in Priština. From early 2001, UNMIK worked with Serbian and union governments to rebuild stable relations in the region. A new assembly for the province was elected in November 2001. It formed a government and chose a president in February 2002.

In January 1998, Milo Đukanović became Montenegro's president. This followed a very close election in October 1997 against Momir Bulatović, who supported Milošević. Đukanović's group then won parliamentary elections in May. Đukanović distanced himself from Milošević. He followed pro-Western policies and supported Montenegro's independence from Serbia. Economic ties with Serbia began to break as Montenegro created a new economic policy and adopted the Deutsche Mark as its currency.

Before October 5, even as opposition grew, Milošević still controlled the government of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (FRY). Although his political party, the Socialist Party of Serbia (SPS), did not have a majority in either the federal or Serbian parliaments, it controlled the governing groups and held all the important government jobs. A key part of Milošević's power was his control of the Serbian police. This was a heavily armed force of about 100,000 people. It was responsible for internal security and was accused of serious human rights abuses.

Regular federal elections in September 2000 resulted in Kostunica getting less than a majority, meaning a second round of voting was needed. Immediately, street protests and rallies filled cities across the country. Serbs gathered to support Vojislav Koštunica, who was the candidate for FRY president from the recently formed Democratic Opposition of Serbia (DOS). There was widespread fear that the second round would be canceled due to foreign interference. Cries of fraud and demands for Milošević's removal were heard across city squares from Subotica to Niš.

Democratic Transition

On October 5, 2000, Slobodan Milošević was forced to accept defeat after days of large protests across Serbia.

The new FRY President Vojislav Koštunica was soon joined at the top of Serbian politics by Zoran Đinđić from the Democratic Party (DS). Đinđić was elected Prime Minister of Serbia as the leader of the DOS in December's elections. After an initial period of excitement following October 5, Koštunica's party (DSS) and the rest of DOS, led by Đinđić and his DS, started to disagree more and more. They argued about the type and speed of the government's reform programs. Although early reform efforts were very successful, especially in the economy, by mid-2002, the nationalist Koštunica and the practical Đinđić were openly fighting. Koštunica's party, which had informally left all DOS decision-making groups, pushed for early elections to the Serbian Parliament to try and remove Đinđić. After the first excitement of replacing Milošević's rule, the Serbian people started to feel tired and disappointed with their leaders by mid-2002. This political deadlock continued for much of 2002, and reform efforts stopped.

In February 2003, the Constitutional Charter was finally approved by both republics and the FRY Parliament. The country's name was changed from Federal Republic of Yugoslavia to Serbia and Montenegro. Under the new Charter, most federal duties and powers were given to the republic level. The office of President of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, held by Vojislav Koštunica, ended when Svetozar Marović was elected President of Serbia and Montenegro.

On March 12, 2003, Serbian Prime Minister Zoran Đinđić was assassinated. The newly formed union government of Serbia and Montenegro reacted quickly. They declared a state of emergency and launched a major crackdown on organized crime, leading to over 4,000 arrests.

Parliamentary elections were held in the Republic of Serbia on December 28, 2003. Serbia had been in a state of political crisis since the overthrow of the former communist ruler, Slobodan Milošević, in 2001. Reformers, led by former Yugoslav President Vojislav Koštunica, had not been able to gain control of the Serbian presidency. This was because three presidential elections in a row failed to get the required 50% voter turnout. The assassination of the reforming Prime Minister, Zoran Đinđić, in March 2003 was a major setback.

Despite a big increase in support for the Radicals, the four pro-reform parties won 49.8% of the vote. These parties were Koštunica's Democratic Party of Serbia, late Prime Minister Đinđić's Democratic Party (Serbia) (now led by Boris Tadić), the G17 Plus group of liberal economists led by Miroljub Labus, and the SPO-NS. The two anti-western parties, the Radicals of Vojislav Šešelj and the Socialists of Milošević, won 34.8% of the vote. The pro-reform parties won 146 seats to 104.

In the 2004 Presidential election, Boris Tadić, candidate of the Democratic Party, won against Tomislav Nikolić of the Serbian Radical Party. This confirmed Serbia's future path towards reform and integration with the European Union.

Republic of Serbia (2006–Present)

In the early 2000s, Montenegro's governments continued policies aimed at independence. Political tensions with Serbia grew, even with political changes in Belgrade. The question of whether the Federal Yugoslav state would continue to exist became a serious issue.

Montenegro voted for full independence in a referendum on May 21, 2006 (55.4% voted yes). Montenegro declared independence on June 3, 2006. This was followed by Serbia's declaration of independence on June 5, 2006. This marked the final breakup of the State Union of Serbia and Montenegro, and Serbia became an independent state again for the first time since 1918.

A referendum was held on October 28 and 29, 2006, on a proposed new Constitution of Serbia. It was approved. This constitution is Serbia's first as an independent state since the Kingdom of Serbia's 1903 constitution.

The 2007 elections confirmed that the Serbian Parliament supported reforms and joining Europe. Tadić's party doubled its number of representatives.

On February 3, 2008, Tadić was re-elected as President.

The Serbian government went through weeks of serious crisis after its southern province of Kosovo unilaterally declared independence on February 17, 2008. This was gradually recognized by the United States and many European Union countries. The crisis was made worse by Prime Minister Vojislav Koštunica of the Democratic Party of Serbia (DSS). He demanded that the Democratic Party (Serbia) (DS), which held the government majority, change the government agreement. He wanted an addition stating that Serbia could only continue European integration if Kosovo remained an integral part of it, as stated in the 2006 Constitution. The DS and G17+ refused. Koštunica had to resign on March 8, 2008. He also asked the President to dissolve parliament and schedule early parliamentary elections.

These early parliamentary elections were held on May 11, 2008, just a year after the previous ones. The results showed that Tadić's ZES coalition gained more votes, going from 87 to 102 seats. After long and difficult talks, a new pro-European government was formed on July 7, 2008. It was supported by 128 out of 250 parliamentary votes from ZES, SPS-PUPS-JS, and 6 out of 7 minority representatives. The new prime minister was Mirko Cvetković, a candidate from the Democratic Party.

In May 2012, nationalist Tomislav Nikolić was elected as President of Serbia. He defeated Tadić in the presidential election. In July 2012, Serbian Socialist Party leader Ivica Dačić became prime minister of Serbia after parliamentary elections. His government was a coalition of President Tomislav Nikolic's nationalist Progressive Party, the Socialist Party, and other groups.

The Serbian Progressive Party (SNS) won the 2014 election. The leader of SNS, Aleksandar Vučić, became prime minister. Three years later, he became president. Ana Brnabic has been prime minister since 2017, but President Vučić has kept strong control over executive power.

Since his election as President of Serbia in 2017, Aleksandar Vučić has worked to build good relationships with European, Russian, and Chinese partners.

In June 2020, Serbia's ruling Progressive Party (SNS) won a huge victory in parliamentary elections. Main opposition groups did not take part in the vote. According to the opposition, the conditions were not fair. In April 2022, President Aleksandar Vučić was re-elected. Vučić's Serbian Progressive Party (SNS) won the early parliamentary election, which happened at the same time as the presidential election.

Kosovo Dispute

On February 17, 2008, self-proclaimed representatives of Kosovo Albanians declared independence. They were acting outside the UN mission's framework. This declaration established the Republic of Kosovo. This was met with mixed reactions from different countries around the world.

In 2013, Serbia and Kosovo began to make their relations more normal, following the Brussels Agreement. However, this process stopped in November 2018 after Kosovo placed a 100 percent tax on goods imported from Serbia. On April 1, 2020, Kosovo removed the tax.

EU Integration

Serbia officially applied to join the European Union on December 22, 2009.

Despite some political challenges, on December 7, 2009, the EU unfroze its trade agreement with Serbia. Also, countries in the Schengen Area removed the visa requirement for Serbian citizens on December 19, 2009.

A Stabilisation and Association Agreement (SAA) was signed in 2008. It officially started on September 1, 2013.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Serbia para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Serbia para niños

- Capitals of Serbia

- List of Serbian monarchs

- List of presidents of Serbia

- Military history of Serbia

| Audre Lorde |

| John Berry Meachum |

| Ferdinand Lee Barnett |