Hopi facts for kids

A Hopi woman in traditional clothing

|

|

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 18,237 (2010) are registered | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| Hopi, English | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Pueblo peoples, Uto-Aztecan peoples |

The Hopi are a Native American tribe who mostly live on the Hopi Reservation in northeastern Arizona. In 2010, there were about 19,338 Hopi people in the United States. The Hopi Tribe is a self-governing nation within the U.S. It works directly with the United States federal government. Most Hopi people are part of the Hopi Tribe of Arizona, but some are part of the Colorado River Indian Tribes. The Hopi Reservation covers about 2,532 square miles (6,558 square kilometers).

The Hopi met Spaniards in the 1500s. They were called "Pueblo people" because they lived in villages, which are called pueblos in Spanish. The Hopi are believed to be related to the Ancestral Puebloans (who the Hopi call Hisatsinom). These ancient people built large apartment-like homes and had a rich culture across the Four Corners area (Utah, Arizona, New Mexico, and Colorado). They lived along the Mogollon Rim from the 12th to 14th centuries. Their culture is thought to have influenced today's Hopi and Pueblo communities.

The word "Hopi" means "behaving one," or someone who is polite, peaceful, and follows the "Hopi Way." This is different from some other tribes that were known for fighting.

The idea of being "Hopi" is very important to their religion and way of life. It means showing respect for everything, living in peace, and following the teachings of Maasaw, who is the Creator or Caretaker of Earth. The Hopi perform traditional ceremonies to help the whole world.

Traditionally, Hopi families are organized into matrilineal clans. This means children belong to their mother's clan. These clans are found in all Hopi villages. Women from the father's clan name the children. After a baby is shown to the Sun, the women of the father's clan gather. They each bring a name and a gift for the child. A child can get many names, sometimes over 40! The family usually picks one common name. Today, many Hopi children also use a non-Hopi or English name. People might also change their name when they join traditional religious groups or after a big life event.

Contents

- Hopi Homes and Villages

- Hopi Government and Laws

- Oraibi Village History

- Early European Encounters (1540–1680)

- The Pueblo Revolt of 1680

- Hopi and U.S. Relations (1849–1946)

- Hopi Recognition and Modern Government

- Hopi–Navajo Land Disputes

- Tribal Government Structure

- Hopi Economic Development

- Hopi Culture and Traditions

- Albinism Among the Hopi

- Notable Hopi People

- Images for kids

- See also

Hopi Homes and Villages

Long ago, Hopi homes were built with a Pueblo style. Archeologists have found different types of rooms from prehistoric Hopi life. These include living rooms, storage rooms, and special religious rooms called kivas. These rooms allowed the Hopi to hold ceremonies, cook, and make hunting tools.

The Hopi have always seen their land as sacred. They believe they are caretakers of the land passed down from their ancestors. They didn't think about dividing land. Farming is very important to them. Today, their villages are located on top of mesas (flat-topped hills) in northern Arizona. The Hopi first lived at the bottom of the mesas. But in the 1600s, they moved to the mesa tops for safety from other tribes and the Spanish.

On December 16, 1882, President Chester A. Arthur created a reservation for the Hopi. It was smaller than the nearby Navajo reservation, which is the largest in the country.

Hopi Government and Laws

On October 24, 1936, the Hopi people approved a Constitution. This set up a government with one main council called the Tribal Council. The powers of the chairman, vice chairman, and judges are limited. The 1936 Constitution made sure that the traditional powers of the Hopi Villages were kept.

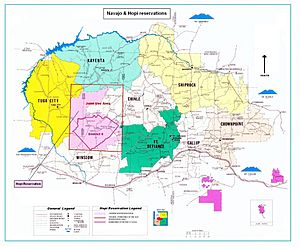

As of 2005, the Hopi Reservation is completely surrounded by the much larger Navajo Reservation. There have been land disagreements between the Hopi and Navajo for a long time. These disputes led to the creation of the Navajo–Hopi Joint Use Area, where both tribes shared land. But this still caused problems. Laws passed in 1974 and 1996 divided this area, known as Big Mountain. This division has also caused ongoing disagreements.

Oraibi Village History

Old Oraibi is one of the oldest Hopi villages. It is also one of the oldest villages in the United States that has been lived in continuously. In the 1540s, it was home to 1,500–3,000 people.

Early European Encounters (1540–1680)

The first time Europeans met the Hopi was in 1540. This was when the Spanish explorer Francisco Vásquez de Coronado came to North America. While visiting the Zuni villages, he heard about the Hopi. Coronado sent Pedro de Tovar to find the Hopi villages. The Spanish wrote that the first Hopi village they saw was Awatovi. They estimated there were about 16,000 Hopi and Zuni people.

Later, another Spanish explorer, García López de Cárdenas, explored the Rio Grande. He also met the Hopi. They welcomed him and his men and helped them on their journey.

In 1582–1583, Antonio de Espejo visited the Hopi. He noted there were five Hopi villages and about 12,000 Hopi people. During this time, the Spanish explored and settled the Southwest. But they didn't send many soldiers or settlers to Hopi land. Their visits were rare and spread out over many years, often for military exploration.

The Spanish settled near the Rio Grande. Since the Hopi didn't live near rivers that connected to the Rio Grande, the Spanish never left troops on their land. Missionaries and Catholic friars came with the Spanish. Starting in 1629, with 30 friars arriving in Hopi country, the Franciscan Period began. The Franciscans built a church at Awatovi.

The Pueblo Revolt of 1680

Spanish Catholic priests tried to convert the Hopi. They also punished them for practicing their own religion. The Spanish forced the Hopi to work and give up their goods and crops. This harsh treatment made the Hopi very unhappy. Records show Spanish abuses. For example, in 1655, a Franciscan priest killed a Hopi man. In 1656, a young Hopi man was sent away as a servant for pretending to be a priest. During the time the Franciscans were there (1629-1680), only the people at Awatovi truly converted.

In the 1670s, the Pueblo Indians near the Rio Grande suggested a revolt in 1680, and the Hopi agreed to help. The Pueblo Revolt was the first time different Pueblo groups worked together to force out the Spanish. In the "Burning of Awatovi," Spanish soldiers, missionaries, and priests were killed. Their churches were taken apart. It took 20 years for the Spanish to regain control over the Rio Grande Pueblos. But the Catholic Inquisition never returned to Hopi land.

In 1700, Spanish friars started rebuilding a church at Awatovi. But during the winter of 1700–01, men from other Hopi villages attacked Awatovi. They did this at the request of the village chief. They killed all the men, moved the women and children to other Hopi villages, and then completely destroyed and burned Awatovi. After this, the Spanish never returned to Hopi country, even though they tried sometimes in the 1700s.

Hopi and U.S. Relations (1849–1946)

In 1849, James S. Calhoun became the official Indian agent for the U.S. Southwest. He was in charge of all Native Americans in the area. The first official meeting between the Hopi and the U.S. government happened in 1850. Seven Hopi leaders traveled to Santa Fe to meet Calhoun. They wanted the government to protect them from the Navajo, who were a different tribe. At this time, the Hopi leader was Nakwaiyamtewa.

The U.S. built Fort Defiance in Arizona in 1851. They sent troops to Navajo land to deal with threats to the Hopi. General James J. Carleton and Kit Carson captured Navajo people and forced them to the fort. This event, known as the Long Walk of the Navajo, gave the Hopi a short time of peace.

In 1847, Mormons settled in Utah and tried to convert Native Americans. Jacob Hamblin, a Mormon missionary, first visited Hopi country in 1858. He got along well with the Hopi. In 1875, an LDS Church was built on Hopi land.

Education for Hopi Children

In 1875, an English trader named Thomas Keam took Hopi leaders to meet President Chester A. Arthur in Washington D.C.. Loololma, the chief of Oraibi at the time, was very impressed with Washington. In 1887, a federal boarding school was opened at Keams Canyon for Hopi children.

The people of Oraibi did not want their children to go to this school, which was 35 miles (56 km) from their villages. The Keams Canyon School was meant to teach Hopi youth European-American ways. It forced them to speak English and give up their traditions. Children were made to abandon their tribal identity and adopt European-American culture. They had to give up their traditional names, clothing, and language. Boys were forced to cut their long hair and learn European farming and carpentry. Girls learned ironing, sewing, and "civilized" dining. The school also pushed European-American religions. Students had to attend services every morning and religious classes during the week.

In 1890, government officials visited the school. Seeing few students, they returned with soldiers. They threatened to arrest Hopi parents who refused to send their children to school. Officials forcibly took children to fill the school.

Hopi Land and Disputes

Farming is a key part of Hopi culture. Their villages are spread across northern Arizona. The Hopi and Navajo did not originally think of land as being divided by boundaries. The Hopi lived in permanent villages, while the nomadic Navajo moved around the Four Corners area. Both lived on the land of their ancestors. On December 16, 1882, President Chester A. Arthur created a reservation for the Hopi. It was smaller than the Navajo reservation, which was the largest in the country.

The Hopi Reservation was a rectangle about 55 by 70 miles (88.5 by 110 km) in the middle of the Navajo Reservation. Their village lands took up about half of this area. The reservation stopped white settlers from moving in, but it didn't protect the Hopi from the Navajos.

The Hopi and Navajo fought over land. They had different ways of using the land, as the Navajo were sheep herders. The Hopi eventually asked the U.S. government to help solve the dispute. The tribes argued over about 1.8 million acres (7,284 square kilometers) of land in northern Arizona. In 1887, the U.S. government passed the Dawes Act. This law aimed to divide tribal land into individual plots for families. The idea was to encourage European-American style farming on small family plots. Any remaining land would be called "surplus" and sold to U.S. citizens. For the Hopi, this act would have destroyed their ability to farm, which was their main way of life. However, the Bureau of Indian Affairs did not set up these land divisions in the Southwest.

The Oraibi Split

The chief of Oraibi, Lololoma, supported Hopi children going to school. But his people were divided. Most of the village was traditional and refused to send their children to school. These people were called "hostiles" because they opposed the American government's efforts to make them change their ways. The rest of Oraibi were called "friendlies" because they accepted white people and their culture. The "hostiles" would not let their children attend school. In 1893, the Oraibi Day School opened in the village. Even though the school was in the village, traditional parents still refused to send their children. The U.S. government often used threats and force, like imprisonment, as punishment.

In November 1894, soldiers arrested eighteen Hopi resisters. Among them were Habema and Lomahongyoma. Later, they realized they hadn't caught everyone. So, Sergeant Henry Henser was sent back to capture Potopa, a Hopi medicine man known as a "dangerous resister." To get rid of all resisters from Oraibi, government officials sent 19 Hopi men they saw as troublemakers to Alcatraz Prison. They stayed there for a year. The U.S. government thought this would stop the Hopi resistance. However, it only made the Hopi feel more bitter and resistant. When the Hopi prisoners returned home, they said government officials told them they didn't have to send their children to school. But when they got back, Indian agents denied this promise.

Another Oraibi leader, Lomahongyoma, competed with Lololoma for village leadership. In 1906, the village split after a conflict between the "hostiles" and "friendlies." The traditional "hostiles" left and formed a new village called Hotevilla.

Hopi Recognition and Modern Government

At the start of the 1900s, the U.S. government set up schools, missions, farming offices, and clinics on every Native American reservation. This policy required each reservation to have its own police, courts, and a leader to represent the tribe to the U.S. government. In the 1910 Census for Native Americans, the Hopi Tribe had 2,000 members, which was the highest in 20 years. The Navajo at this time had 22,500 members and have continued to grow. In the early 1900s, only about three percent of Hopi people lived off the reservation. In 1924, Congress officially declared Native Americans to be U.S. citizens with the Indian Citizenship Act.

Under the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934, the Hopi created a constitution to form their own tribal government. In 1936, they elected a Tribal Council. The beginning of the Hopi constitution says they are a self-governing tribe. It focuses on working together for peace and agreements between villages to keep the "good things of Hopi life." The constitution has 13 articles, covering their land, who can be a member, and how their government is organized with law-making, leadership, and court branches.

From the 1940s to the 1970s, the Navajo moved their settlements closer to Hopi land. This caused the Hopi to bring the issue to the U.S. government. This led to the creation of "District 6," which drew a boundary around the Hopi villages on the first, second, and third mesas. This made the reservation smaller, about 501,501 acres (2,029 square kilometers). In 1962, courts ruled that the U.S. government did not give the Navajo permission to live on the 1882 Hopi Reservation. It also stated that the remaining Hopi land should be shared with the Navajo, as the Navajo–Hopi Joint Use Area.

From 1961 to 1964, the Hopi tribal council signed agreements with the U.S. government. These allowed companies to look for and drill for oil, gas, and minerals on Hopi land. This drilling brought over three million dollars to the Hopi Tribe. In 1974, the Navajo-Hopi Land Settlement Act was passed. This was followed by the Navajo-Hopi Land Dispute Settlement Act of 1996, which solved some remaining issues. The 1974 Act created the Office of Navajo and Hopi Indian Relocation. This office forced any Hopi or Navajo living on the other's land to move. In 1992, the Hopi Reservation grew to 1.5 million acres (6,070 square kilometers).

Today, the Hopi Reservation has Arizona State Route 264 running through it. This paved road connects the many Hopi villages.

Tribal Government Structure

On October 24, 1936, the Hopi people approved their constitution. This constitution created a government with one main council where all powers are held by the Tribal Council. While there is a chairman, vice chairman, and judges, their powers are limited by the Hopi Constitution. The traditional powers of the Hopi villages were kept in the 1936 constitution.

The Hopi tribe is officially recognized by the U.S. government. Its main office is in Kykotsmovi, Arizona.

Tribal Officers

The current tribal officers are:

- Chairman: Timothy L. Nuvangyaoma

- Vice Chairman: Clark W. Tenakhongva

- Tribal Secretary: Theresa Lomakema

- Treasurer: Wilfred Gaseoma

- Sergeant-at-Arms: Alfonso Sakeva

Tribal Council Members

Representatives for the council are chosen either by a community vote or by the village leader (kikmongwi). Each representative serves for two years. As of December 2017, the Tribal Council had members from these villages:

- Village of Upper Moenkopi: Hubert Lewis, Sr., Michael Elmer, Robert Charley, Philton Talahytewa, Sr.

- Village of Bacavi: Dwayne Secakuku, Clifford Quotsaquahu

- Village of Kykotsmovi: David Talayumptewa, Phillip Quochytewa, Sr., Danny Honanie, Herman G. Honanie

- Village of Sipaulavi: Rosa Honanie

- Village of Mishongnovi: Emma Anderson, Craig Andrews, Pansy K. Edmo, Rolanda Yoyletsdewa

- First Mesa Consolidated Villages: Albert T. Sinquah, Ivan Sidney, Sr., Wallace Youvella, Jr., Dale Sinquah

Currently, the villages of Shungopavi, Oraibi, Hotevilla, and Lower Moenkopi do not have representatives on the council. Hopi Villages choose their council representatives and can decide not to send any. This decision has been approved by the Hopi Courts.

Tribal Courts

The Hopi Tribal Government has a Trial Court and an Appellate Court in Keams Canyon. These courts follow a Tribal Code, which was updated on August 28, 2012.

Hopi Economic Development

The Hopi tribe gets most of its money from natural resources. On the 1.8 million acre (7,284 square kilometer) Navajo Reservation, a lot of coal is mined each year. The Hopi Tribe shares in the money from these mineral sales. Peabody Western Coal Company is one of the biggest coal mining operations on Hopi land.

The tribe's budget for 2010 was $21.8 million. They expected to earn $12.8 million from mining that year.

The Hopi Tribe Economic Development Corporation (HTEDC) is a tribal business that works to create different ways for the tribe to earn money. The HTEDC oversees the Hopi Cultural Center and Walpi Housing Management. Other HTEDC businesses include the Hopi Three Canyon Ranches, the 26 Bar Ranch, three properties in Flagstaff, and a hotel in Sedona.

Tourism is also a source of income. The Moenkopi Developers Corporation, a non-profit group owned by the Upper village of Moenkopi, opened the 100-room Moenkopi Legacy Inn and Suites in Moenkopi, near Tuba City. This is the second hotel on the reservation. It offers a place for visitors to stay, attend talks, and see demonstrations. This project is expected to create 400 jobs. The village also runs the Tuvvi Travel Center in Moenkopi. The tribe also owns and operates the Hopi Cultural Center on Second Mesa. It has gift shops, museums, a hotel, and a restaurant that serves Hopi dishes.

The Hopi people have often voted against having gambling casinos as a way to make money.

On November 30, 2017, the Hopi Tribe and the State of Arizona signed a gaming agreement. This agreement allows the Hopi Tribe to operate or lease up to 900 gaming machines. This made Hopi the 22nd and last Arizona tribe to sign such an agreement.

Hopi Culture and Traditions

The Hopi Dictionary says the main meaning of "Hopi" is "behaving one, one who is mannered, civilized, peaceable, polite, who follows the Hopi Way." Some sources say this is why they are called "The Peaceful People." However, some experts say the word doesn't directly mean "peaceful."

According to Barry Pritzker, many Hopi feel a strong connection to their past. For them, time doesn't always move in a straight line. The past can feel like it's happening now. In their current "Fourth World," the Hopi worship Masauwu. He told them to "always remember their gods and to live in the correct way." The village leader, kikmongwi, helps promote good behavior and community spirit.

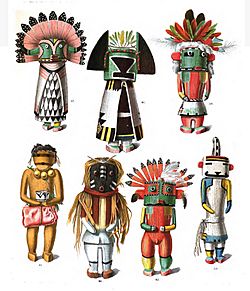

Traditionally, Hopi families are organized into matrilineal clans. This means that when a man marries, his children belong to his wife's clan. These clan groups are found across all villages. Women from the father's clan name the children. On the 20th day of a baby's life, these women gather. Each brings a name and a gift for the child. Sometimes, a child can be given over 40 names! The child's parents usually choose which name to use. Today, people often use a non-Hopi or English name, or a Hopi name chosen by the parents. A person might also change their name when they join one of the religious groups, like the Kachina society, or after a big life event.

The Hopi practice a full cycle of traditional ceremonies. These ceremonies follow the lunar calendar and happen in each Hopi village. Like other Native American groups, the Hopi have been influenced by Christianity. However, few have converted enough to Christianity to stop their traditional religious practices.

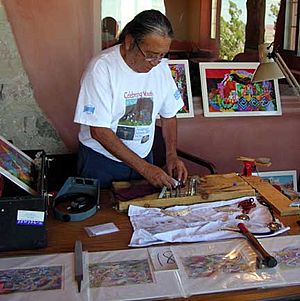

Traditionally, the Hopi are small-scale farmers who grow food for themselves. The Hopi are also part of the wider economy. Many Hopi have regular jobs. Others earn a living by creating Hopi art, such as carving Kachina dolls, making pottery, and designing beautiful jewelry, especially from sterling silver.

The Hopi collect and dry a native plant called Thelesperma megapotamicum, also known as Hopi tea. They use it to make an herbal tea, as a medicine, and to make a yellow dye.

Albinism Among the Hopi

The Hopi have a high rate of albinism. This is especially true in Second Mesa and villages towards Hotevilla. About 1 in 200 individuals are affected.

Notable Hopi People

- Thomas Banyacya (ca. 1909–1999), a spokesman for traditional Hopi leaders.

- Neil David Sr. (born 1944), a painter, illustrator, and kachina doll carver.

- Dan Evehema (born circa 1893 - 1999), a traditional Hopi leader and author.

- Jean Fredericks (1906–1990), a Hopi photographer and former Tribal Council chairman.

- Iva Honyestewa, a basket maker, food activist, and educator.

- Diane Humetewa (born 1964), appointed as a U.S. District Court Judge by President Obama.

- Fred Kabotie (circa 1900–1986), a painter and silversmith.

- Michael Kabotie (1942–2009), a painter, sculptor, and silversmith.

- Charles Loloma (1912–1991), a jeweler, ceramic artist, and educator.

- Linda Lomahaftewa, (born 1947) a printmaker, painter, and educator.

- David Monongye (birth date unknown), a traditional Hopi leader.

- Helen Naha (1922–1993), a potter.

- Tyra Naha, a potter.

- Dan Namingha, (born 1950), a Hopi-Tewa painter and sculptor.

- Elva Nampeyo, a potter.

- Fannie Nampeyo, a potter.

- Iris Nampeyo (Nampeyo, Hopi, circa 1860–1942), a famous potter.

- Lori Piestewa (1979–2003), a U.S. Army soldier who died in the Iraq War.

- Dextra Quotskuyva (born 1928), a potter.

- Emory Sekaquaptewa (1928–2007), a Hopi leader, linguist, and jeweler.

- Phillip Sekaquaptewa (born 1956), a jeweler and silversmith (nephew of Emory).

- Don C. Talayesva (ca. 1891–1985), an autobiographer and traditionalist.

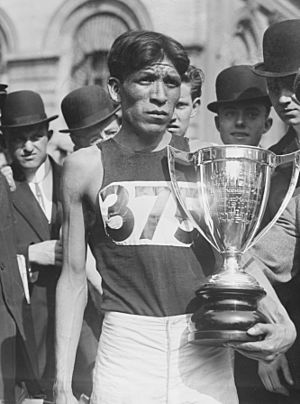

- Lewis Tewanima (1888–1969), an Olympic distance runner and silver medalist.

- Tuvi (Chief Tuba) (circa 1810–1887), the first Hopi to convert to Mormonism. Tuba City, Arizona, was named after him.

Images for kids

-

Hopi Women's Dance, 1879, Oraibi, Arizona, photo by John K. Hillers

-

Traditional Hopi village of Walpi, 1941, photo by Ansel Adams

-

Traditional Hopi homes, c. 1906, photo by Edward S. Curtis

-

Hopi girl, photo by Edward S. Curtis

-

Iris Nampeyo, world-famous Hopi ceramist, with her work, c. 1900, photo by Henry Peabody

-

Four young Hopi women grinding grain, c. 1906, photo by Edward S. Curtis

-

Hopi girl, 1922, photo by Edward S. Curtis

-

Hopi woman, 1922, photo by Edward S. Curtis

-

Hopi girls, 1922, photo by Edward S. Curtis

See also

In Spanish: Hopi para niños

In Spanish: Hopi para niños

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |