Katharine Cornell facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Katharine Cornell

|

|

|---|---|

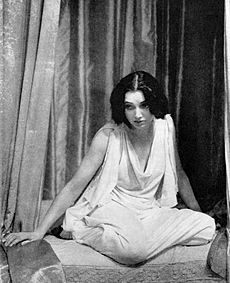

Cornell as Mary Fitton in the Broadway production of Clemence Dane's Will Shakespeare (1923)

|

|

| Born | February 16, 1893 |

| Died | June 9, 1974 (aged 81) Tisbury, Massachusetts, U.S.

|

| Resting place | Tisbury Village Cemetery |

| Occupation |

|

| Years active | 1921–1960 |

| Spouse(s) |

Guthrie McClintic

(m. 1921; died 1961) |

Katharine Cornell (February 16, 1893 – June 9, 1974) was a famous American stage actress. She was also a writer, theater owner, and producer. Born in Berlin to American parents, she grew up in Buffalo, New York.

A critic named Alexander Woollcott called her "The First Lady of the Theatre." She was the first person to win the Drama League Award in 1935 for her role in Romeo and Juliet. Katharine Cornell was known for her important roles in serious plays on Broadway. Her husband, Guthrie McClintic, often directed these plays. They started their own company, C. & M.C. Productions, Inc. This company allowed them to choose and produce plays freely. Many famous actors of the 20th century got their first or big roles through their company.

Cornell is seen as one of the greatest actresses in American theater history. Her most famous role was playing the English poet Elizabeth Barrett Browning. This was in the 1931 Broadway show The Barretts of Wimpole Street. She also appeared in other Broadway plays. These included The Letter (1927), The Alien Corn (1933), and Romeo and Juliet (1934). She won a Tony Award for her role as Cleopatra in Antony and Cleopatra (1947).

Unlike many actresses of her time, Cornell usually avoided movie roles. She appeared in only one Hollywood film. This was Stage Door Canteen, a movie made to boost spirits during World War II. In it, she played herself. She did act in TV versions of The Barretts of Wimpole Street and There Shall Be No Night. She also narrated the documentary Helen Keller in Her Story, which won an Oscar.

Katharine Cornell was admired for her elegant and romantic stage presence. She was mostly known for playing serious, dramatic roles. Her appearances in comedies were rare. When she did comedy, people praised her warmth more than her humor. She died on June 9, 1974, in Tisbury, Massachusetts, at age 81. She is buried in the Tisbury Village Cemetery.

Contents

Growing Up in Buffalo

Katharine Cornell was born into a well-known, wealthy family from Buffalo, New York. Her family was distantly related to Ezra Cornell, who founded Cornell University. Her great-grandfather, Samuel Garretson Cornell, started Cornell Lead Works in the 1850s. Katharine's parents, Peter and Alice, lived in Berlin when Peter was studying medicine. Katharine was born there.

Six months later, her family moved back to Buffalo. As a child, Katharine often played make-believe with imaginary friends in her backyard. She soon began performing in school plays and pageants. She also watched family shows in her grandfather's attic theater. She loved sports, too. She was a runner-up in the city tennis championship and an amateur swimming champion. She attended the University of Buffalo. In 1913, she joined The Garret Club, a women's club, and took part in their plays.

After she became famous, Cornell often brought her plays to Buffalo. She never lived there again, but she loved her hometown. A writer named Tad Mosel said she would walk slowly after leaving her hotel in Buffalo. She would smile at everyone so they could feel close to her. On opening nights in Broadway, family and friends from Buffalo would greet her backstage. Many of her plays were performed at the Erlanger Theater in Buffalo.

Starting Her Acting Career

In 1915, Cornell's mother passed away. Katharine inherited enough money to live on her own. She moved to New York City to become an actress. She joined the Washington Square Players, a theater group. People quickly saw her as a very promising actress. After two seasons, she joined Jessie Bonstelle's company. This was a leading theater group that performed in Detroit and Buffalo during the summers. By age 25, Cornell was getting excellent reviews for her acting.

Cornell performed with several theater companies that toured the East Coast. In 1919, she went to London with the Bonstelle company. She played Jo March in a play based on Louisa May Alcott's novel Little Women. Critics didn't like the play much, but they all praised Cornell. One paper, The Englishwomen, wrote that "London is unanimous in its praise."

When she returned to New York, she met Guthrie McClintic, a young theater director. Cornell made her Broadway debut in a small role in the play Nice People.

Her first big Broadway role was Sydney Fairfield in A Bill of Divorcement (1921). The New York Times said her performance was "memorable." The play ran for 173 shows, which was a success.

She married Guthrie McClintic on September 8, 1921, in Cobourg, Ontario, Canada. They later bought a house in Manhattan.

Becoming a Star

In 1924, Cornell and McClintic joined The Actor's Theatre. For their first play, they chose Candida by George Bernard Shaw. Cornell changed how people saw the play. She made the character Candida the most important part. Critics loved her performance, and audiences agreed. The theater group decided that Cornell's name must be featured above the play's title. Another theater group, the Theatre Guild, owned the rights to Shaw's plays. They only allowed Cornell to play Candida during her lifetime. Shaw himself later told her she had created "an ideal British Candida."

Cornell's next role was Iris March in The Green Hat (1925). This play became a huge hit even before it reached New York. Critics often said the play itself wasn't great. But they found it amazing because of Cornell's powerful acting. Critic George Jean Nathan wrote that Cornell "stands head and shoulders above all the other young women of the American theater."

The Green Hat ran for 231 shows in New York. Its success even started a fashion trend for green hats like the one Cornell wore.

In 1927, she starred in The Letter by W. Somerset Maugham. She played Leslie Crosbie, a woman who kills her lover. Maugham himself suggested Cornell for the role. By then, Cornell had many loyal fans. The opening night was such a big event that the New York Sun reported sidewalks were packed with people hoping to see her.

In 1928, Cornell played the main role of Countess Ellen Olenska in a play based on Edith Wharton's novel The Age of Innocence. Her performance received only positive reviews. After this, Cornell was offered the lead in The Dishonored Lady. This was a dramatic play about a real-life murder. One critic complained about the play's "fifth rate claptrap." But Cornell was respected for making any role her own.

The Barretts of Wimpole Street

Katharine Cornell is perhaps most famous for her role as poet Elizabeth Barrett Browning. This was in Rudolf Besier's play The Barretts of Wimpole Street. The play tells the story of the poet's family life.

The play had some challenges. The main character, Elizabeth, starts out very obedient to her father. Yet, she must be the center of attention. Also, for the first half, Elizabeth has to lie still on a sofa in a heavy Victorian dress. Many people, including actor Lionel Barrymore, thought the play was too old-fashioned. Twenty-seven New York producers turned it down. But Guthrie McClintic read it and found it very moving.

McClintic found Brian Aherne in London to play Robert Browning. For every show, Cornell wore special old jewelry in the last act. This was when her character left her family home. Katharine Hepburn was chosen for the part of Henrietta, but could not sign a contract. Casting the dog was tricky. It had to lie still on stage for a long time. McClintic chose an eight-month-old cocker spaniel. It played the role for the entire run and many shows afterward, getting huge applause.

Cornell bought The Barretts of Wimpole Street for McClintic in December 1930. It was the first play produced by the Cornell-McClintic Corporation. This company was formed on January 5, 1931. Cornell was the producer-manager, and McClintic was the director. McClintic directed the three-hour play with great care for historical details. The play first opened in Cleveland, then in Buffalo, and finally in New York in January 1931.

Critics praised her acting using words like "superb" and "luminous." Dorothy Parker, known for her sharp wit, said she "paid it the tribute of tears." She added, "Miss Katharine Cornell is a completely lovely Elizabeth Barrett." The play ran for 370 performances. When it was announced to close, all remaining tickets sold out.

The play's success led to new interest in Robert Browning's poetry. Cocker spaniels also became very popular dogs that year. Hollywood wanted Cornell to play her role in a movie version. But she refused. She had seen audiences laugh at old movies and didn't want that to happen to her. The movie was made with most of the original cast, but Norma Shearer played Elizabeth.

The 1933–1934 Tour

After Barretts closed, Cornell played leading roles in two more plays: Lucrece (1932) and Alien Corn (1933). Her success in Lucrece led to her being on the cover of Time magazine in December 1932.

Her next big production was Romeo and Juliet, directed by McClintic. Basil Rathbone played Romeo, and Cornell played Juliet. This was her first time performing in a Shakespearean play. Shakespeare's plays were not very popular in the U.S. at that time.

Romeo and Juliet opened in Buffalo in November 1933. Modern dance pioneer Martha Graham created the dance scenes. In Buffalo, Graham thought Juliet's costume for the balcony scene was wrong. She quickly made a new flowing robe for Cornell just before the show.

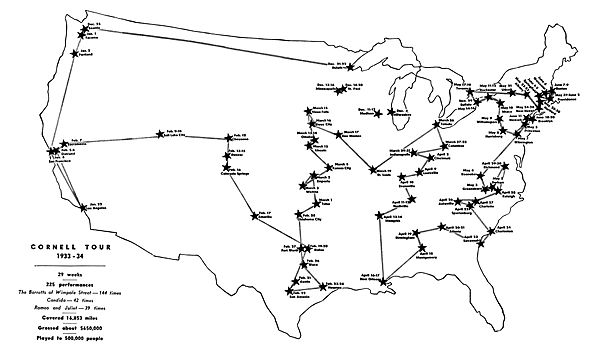

The production then began a seven-month tour across the country. They performed three plays: Romeo and Juliet, The Barretts of Wimpole Street, and Candida. Many theater experts thought this was too ambitious, especially during the Great Depression. It was the first time anyone had tried a national tour with a full Broadway show, let alone three plays. The company visited cities like Milwaukee, Seattle, Los Angeles, and New Orleans.

Movies had largely replaced live theater. Many smaller cities on the tour had not seen a live play since First World War, or ever. But the tour broke box office records in most places. In New Orleans, women rioted when tickets sold out. Variety reported that the tour gave 225 performances to 500,000 people. People from far away traveled to see a show. The towns gained extra money from restaurants and hotels.

A famous story from the tour happened on Christmas night in Seattle. The troupe was supposed to perform Barretts. They planned to arrive in the morning, but it had been raining for 23 days. Roads and railroads were flooded. The train moved very slowly. The theater manager kept sending telegrams saying the show was sold out and the audience was waiting. The train finally arrived in Seattle at 11:30 pm. A crowd was waiting at the station. The manager told Cornell that the audience was still waiting. McClintic asked, "how many?" The manager replied, "The entire house, Twelve hundred people." Cornell was shocked. "Do you mean they want a performance at this hour?" she asked. "They're expecting it," he said.

All 55 cast and crew members went to the theater. They had to protect the sets and props in the rain. The audience streamed back to their seats. Cornell decided the audience could watch the sets being unpacked and put up. So, she raised the curtain. Stagehands and electricians worked to set up in one hour what usually took six. By 1 am, the play began. A biographer wrote that the audience had shown great faith by waiting. The actors gave an amazing performance. When the final curtain fell at 4 am, they received more applause than ever.

The troupe's publicist, Ray Henderson, got this story in every newspaper in America. Alexander Woollcott later made it a tradition on his radio show, The Town Crier. For years, every Christmas, Woollcott told the story of the Seattle audience that waited until 1 am to see Katharine Cornell.

Broadway Successes and New Style

Romeo and Juliet in New York

After their tour, Cornell and McClintic decided to open Romeo and Juliet in New York with a completely new production. McClintic started fresh with only a few actors from the tour. Orson Welles played Tybalt, making his Broadway debut. Brian Aherne played Mercutio, Basil Rathbone was Romeo, and Edith Evans played the Nurse. McClintic wanted the play to feel "light, gay, hot sun, spacious." He also taught Cornell to focus on the meaning and emotion of the lines, rather than just the poetic rhythm.

This was a big change from past productions. McClintic brought back the play's opening speech and kept almost all 23 scenes. For the first time, the strong feelings, youthful romance, and everyday language of the play were given equal importance.

The play opened in December 1934. Reviews were excellent. Burns Mantle called Cornell "the greatest Juliet of her time." Critics noted her fresh approach. Richard Lockridge wrote that Cornell played Juliet as "an eager child, rushing toward love." Cornell herself said her secret was to keep her acting simple. John Mason Brown wrote that Cornell's Juliet was "luscious and charming." He called it "the most lovely and enchanting Juliet our present-day theatre has seen." This role was a turning point for her. It meant she could now take on the most challenging classic roles.

The Barretts Revived

Romeo and Juliet closed in February 1935. Two nights later, the company brought back The Barretts of Wimpole Street. Burgess Meredith had his first big Broadway role in this production. Critics felt this new version was even better. However, it closed after three weeks because other plays were already planned.

The next play, Flowers of the Forest, was an anti-war play. It only ran for 40 performances and was one of Cornell's biggest failures.

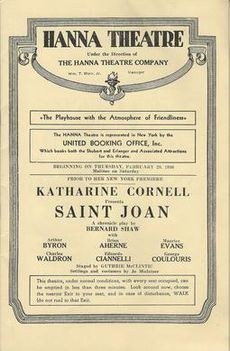

St. Joan

For the next season, Cornell and her husband chose St. Joan by George Bernard Shaw. McClintic cast Maurice Evans as the Dauphin and Tyrone Power in another role. The play opened in March 1936. Critics praised Cornell's performance. John Anderson wrote, "Miss Cornell is superb in it. She is beautiful to look at and her performance is enkindled by the spiritual exaltation."

In this play, Cornell's true artistry shone. Audience members said her performance "changed" them and left them "mesmerized." Writer S.N. Behrman said audiences felt "something essential in herself, as a person." Others called her "magnetic."

The play closed in spring 1936 because the company had already agreed to produce The Wingless Victory. Saint Joan then went on a seven-week tour to five major cities.

Flush, the spaniel dog who played Flush in Barretts, died in July 1937. He had performed his role 709 times and traveled over 25,000 miles on tours. When he died, the Associated Press shared the story worldwide.

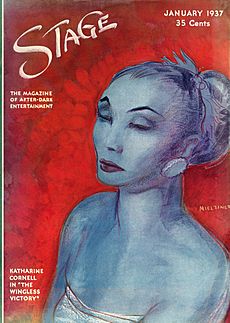

The Wingless Victory

In Maxwell Anderson's The Wingless Victory, McClintic avoided the usual "star entrance." Instead, another character entered first, and then Cornell was revealed to already be on stage. This surprised the audience. The play opened in 1936. Reviews were mixed, but Cornell was still admired for making any role her own. Critic Brooks Atkinson called Cornell "Our Queen of tragedy, a thoughtful actress and a great one."

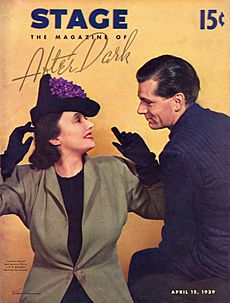

After this, Cornell took a year off. She wrote her memoir, I Wanted to Be an Actress, which was published in 1939.

No Time for Comedy

Cornell starred in her second comedy, No Time for Comedy by S. N. Behrman. McClintic cast the young Laurence Olivier in a main role. During rehearsals, Cornell struggled with comedic timing. Olivier defended her, saying, "Poor old Kit is the most successful woman in the American theater!"

The play opened in April 1939. It became one of Cornell's biggest money-makers. With some cast changes, including Olivier, the play went on a nationwide tour.

The Doctor's Dilemma

Cornell next performed in Shaw's play, The Doctor's Dilemma, with Raymond Massey as her co-star. Massey noted that Cornell was a very smart businesswoman. He said, "She knew everything that was going on and she made all the decisions."

The play opened in 1941 in San Francisco, just one week before Pearl Harbor. It was the only show not canceled despite many blackouts. Because of the war, the play was not well received. Gregory Peck was part of the tour.

The War Years

Soon after the U.S. entered World War II, Cornell decided to revive Candida. This was to raise money for the Army Emergency Fund and the Navy Relief Society. This production featured a cast of stars, including Raymond Massey and Burgess Meredith. Cornell convinced all the actors, Shaw, and the theater staff to donate their work. This way, almost all the money went directly to the fund.

The Three Sisters

A year later, Ruth Gordon encouraged McClintic to produce Anton Chekhov's Three Sisters. Judith Anderson played Olga, and Cornell played Masha. Other actors included Edmund Gwenn and Kirk Douglas in his Broadway debut. The play opened in Washington in December 1942. It was not expected to be a big financial success. However, it ran for 122 performances in New York and then toured. It had the longest run of any Chekhov play in the U.S. at that time.

Time Magazine wrote that Katharine Cornell was "the top-ranking actress in the U.S. theater." Cornell was featured on the cover of Time magazine for the second time in December 1942, with Judith Anderson and Ruth Gordon.

Wartime Service

Cornell's only film role was speaking a few lines from Romeo and Juliet in the movie Stage Door Canteen (1943). This movie featured many Broadway actors. It was made by the American Theatre Wing for War Relief. This group also created the Stage Door Canteen to entertain troops. Cornell volunteered her time cleaning tables at the Canteen.

General George C. Marshall asked Cornell to perform a play for troops in Europe. Cornell decided to take The Barretts of Wimpole Street on tour with the USO. However, the USO thought soldiers would not sit through a three-hour play about Victorian poets. They suggested a different play, Blithe Spirit. But Cornell insisted on Barretts. She said if she was going to entertain soldiers, she must give them her very best. The Army then asked them to cut the love scenes and prepare for rude audiences. Cornell and her company refused. They played their roles exactly as they did on Broadway.

At the first show, the Army's fears seemed true. The play starts in chilly London, and a doctor suggests Elizabeth go to Italy for rest. The audience, American soldiers fighting in Italy, burst into laughter. Actress Margalo Gillmore said they thought the laughter would never stop. But Cornell and McClintic handled it. Gillmore said, "Kit had a shining light in her." She felt the audience change from doubt to full attention. "We've seen an audience born," Cornell said.

The tour opened in Santa Maria, Italy, in 1944. Soldiers lined up hours early and thanked the cast afterward. Brian Aherne wrote that after one show, a paratrooper said, "Told ya it would be better than going to a cat house." The Army then approved two more weeks. The company performed for six months across Italy and then in France. In Paris, Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas wanted to see the play. But performances were only for enlisted soldiers. They got disguises and were able to see the show. The cast also visited hospitals every day.

Cornell, then 51, was told by the Army to stay in Paris. But she wanted to be as close to the front lines as possible. The company performed in the Netherlands, just eight miles from the front. The tour ended in London during German V-2 bomb attacks.

After returning to New York, Cornell found many letters from soldiers. They thanked her for "the most nerve-soothing remedy for a weary G.I." and for reminding them that "a woman is not all leg." Many said it was the first time they had heard from their loved ones in years.

After the war, Cornell helped lead the Community Players. This group helped war veterans and their families when they returned home.

After the War

Candida, Revived

After the war, American theater styles began to change. Cornell revived Candida for the fifth and last time in April 1946. Marlon Brando played the role of the young Marchbanks. Cornell represented an older, romantic style. Brando showed the newer "Method Acting," which focused on deep psychological understanding. Reviews were good, but some audiences found the play less relevant to post-war life.

As she was in her mid-50s, it became harder to find suitable roles. Newer roles simply weren't her style.

Shakespeare and Anouilh

In 1946, Cornell chose Shakespeare's Antony and Cleopatra. This was a challenging role that suited her well. Critics praised her "beauty and power and grandeur." Her presence ensured this play had its longest run ever, with 251 performances.

She then performed in Jean Anouilh's play Antigone. Sir Cedric Hardwicke played King Creon, and Marlon Brando was The Messenger. After the opening, her friend Helen Keller told her, "This play is a parable of humanity. It has no time or space."

Cornell also produced another revival of Barretts of Wimpole Street. This was an eight-week tour to the West Coast. The cast included Tony Randall, Maureen Stapleton, Eli Wallach, and Charlton Heston.

Later Plays

Finding good roles continued to be a challenge. In 1951, Cornell played the lead in Somerset Maugham's comedy, The Constant Wife. This play, starring her favorite co-star Brian Aherne, earned more money for her company than any other play.

In 1953, Cornell found a good role in The Prescott Proposals. Christopher Fry wrote a play called The Dark is Light Enough. The cast included Tyrone Power and Lorne Greene. (Christopher Plummer was Power's understudy.) Plummer later called Cornell "the last of the great actress-managers."

In 1957, Cornell staged There Shall Be No Night, a play that won the Pulitzer Prize. It was updated to reflect the Hungarian Revolution of 1956. This play was also adapted for TV. Another play by Fry, The Firstborn, was set in Biblical Egypt. Leonard Bernstein wrote two songs for the production.

Cornell continued with several other plays. Her last production was Dear Liar in 1960.

Cornell took a three-year break from 1955 to 1958 to recover from a lung operation. Even with good reviews, ticket sales sometimes slowed down. By the end of the 1950s, her production company was no longer active. In 1954, she narrated the film The Unconquered, about her friend Helen Keller.

Starting in the 1940s, she began receiving many awards and honorary degrees from colleges and universities.

Radio Appearances

Cornell made her radio debut on May 6, 1951. She appeared on Theatre Guild on the Air, which featured the first radio broadcast of Shaw's Candida. She also appeared on The Theatre Guild on the Air in April 1952, playing Florence Nightingale.

Retirement

Guthrie McClintic died in October 1961. They had just celebrated their 40th wedding anniversary. Since he had directed all her plays since their marriage, Cornell decided to retire from the stage. She sold her homes and bought a house in Manhattan. She also bought an old building on Martha's Vineyard called The Barn and restored Association Hall on the island.

For her 80th birthday in 1973, an assistant made a tape of birthday greetings. It included messages from famous actors like Laurence Olivier and John Gielgud. The tape was seven and a half hours long! She died from pneumonia on June 9, 1974, at The Barn in Tisbury, Massachusetts.

Thoughts on Acting and Theater

Cornell was on the Board of Directors for The Rehearsal Club. This club was a place for young actresses to stay while looking for work. It also offered support for their careers. Sometimes, Cornell would serve food to the women. McClintic often found small roles for them in his plays.

In her memoir, Cornell wrote about acting. She believed that quick success in movies sometimes hurt young people studying for the stage. She said, "The success stories that we read in the Hollywood magazines make it all sound too easy." She felt that getting started in theater still needed a lot of luck. A producer had to see the right person at the right time. To get that chance, a young actress had to keep trying and visit many managers' offices.

Cornell also believed that when a chance came, an actress needed to be ready. She felt many young girls who came to her for parts had not worked hard enough. She said they had many chances in New York to learn more. They could see great art, hear wonderful music, and read good books. Most importantly, they could watch the best actors perform. She noticed that some young actresses thought it was beneath them to sit in the top balcony of a theater.

Cornell thought the most important thing for young actresses was to learn to use their voices well. She found that reading French aloud helped her a lot. She believed French made her use her mouth more than any other language. She would sometimes read a French book aloud before a performance.

Katharine Cornell's Legacy

Katharine Cornell was one of the most respected and adaptable stage actresses of the early to mid-20th century. She could easily move from comedies to dramas, and from classic plays to modern ones. She was especially good at playing romantic and complex characters.

Theaters and Research Centers

The Tisbury Town Hall on Martha's Vineyard has a theater on its second floor. It was once called Association Hall. It was renamed "The Katharine Cornell Theater" in her honor. A gift from her estate paid for renovations and murals by local artist Stan Murphy. The Katharine Cornell Theater is a popular place for plays, music, and movies. Her grave and a memorial are next to the theater.

There is another theater space named after her at the State University of New York at Buffalo. Many student plays are performed there all year.

The Katharine Cornell-Guthrie McClintic Special Collections Reading Room opened in April 1974. It is at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts at Lincoln Center. The Billy Rose Theatre Division there has many old documents and items related to Cornell and McClintic.

Smith College has a collection of Cornell's papers from 1938 to 1960. The New York Public Library also has letters between a Russian dance critic and Cornell's assistants.

Cornell donated some of her costumes, designed by the famous Russian fashion designer Valentina, to the Museum of the City of New York. These include costumes from her roles in Cleopatra and Antigone.

Cornell and Anthony Quayle recorded a scene from Barretts for an LP record. Cornell also recited poems by Elizabeth Barrett. Cornell's short scene in Stage Door Canteen can be seen on YouTube. In it, she recites lines from Romeo and Juliet.

The Paley Center for Media

The Paley Center for Media has recordings of Cornell's television appearances:

- On April 2, 1956, NBC TV broadcast a production of Barretts. Anthony Quayle played Robert Browning.

- She was also in Hallmark Hall of Fame's production of Robert E. Sherwood's play, There Shall Be No Night. This was broadcast on NBC on March 17, 1957.

- On January 6, 1957, Dave Garroway interviewed Cornell for Wide Wide World: A Woman's Story.

- She appeared on TV as herself for an NBC Symphony Orchestra broadcast on March 22, 1952. She was also interviewed three times for the radio program Stage Struck.

Awards and Honors

Katharine Cornell was one of the first three actresses to win a Tony Award in 1947 (for the 1948 award year). She won for her performance in Antony and Cleopatra. She also received the first New York Drama League Award in 1935 for her role as Juliet. In March 1937, Eleanor Roosevelt gave her the Chi Omega sorority's National Achievement Award at the White House.

Cornell received a medal "for good speech on the stage" from the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. She was also named Woman of the Year by the American Friends of the Hebrew University in 1959. After her role in St. Joan, she received honorary degrees from several universities.

In January 1974, she received the American National Theater and Academy's National Artist Award. This was for her "incomparable acting ability" and for "having elevated the theater throughout the world." In 1935, the University of Buffalo awarded her the Chancellor's Medal. The Artvoice newspaper in Buffalo gives the Katharine Cornell Award each year. It honors a visiting artist for their great contribution to Buffalo's theater community.

The townhouse at 23 Beekman Place, where Cornell and her husband lived, has a historical marker. It honors their importance to New York City.

Katharine Cornell was one of the first members chosen for the American Theatre Hall of Fame when it started in 1972.

Biographies and Artworks

- Katharine Cornell wrote her own story, I Wanted to Be an Actress, in 1939.

- Guthrie McClintic wrote Me & Kit in 1955.

- Lucille M. Pederson wrote Katharine Cornell: A Bio-bibliography in 1994.

- Gladys Malvern wrote Curtain Up! The Story of Katharine Cornell in 1943.

- Inspired by The Barretts of Wimpole Street, Virginia Woolf wrote Flush: A Biography in 1933. This was a fictional story about Elizabeth Barrett's dog.

The Smithsonian Institution has a bronze bust of Cornell from 1961 by artist Malvina Hoffman. It also has a pastel portrait by William Cotton from 1933.

The Albright-Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo, New York, has a full-length portrait of Cornell from 1926. It shows her in her role as Candida. The gallery also has a life mask, a drawing, and two sculptures of her.

The Armstrong Browning Library at Baylor University has a portrait of Cornell as Elizabeth Barrett. Cornell donated this portrait and other items related to Barretts to the library.

The State University of New York at Buffalo has a portrait of Cornell painted by the surrealist artist Salvador Dalí in 1951.

Cartoonist Alex Gard created a drawing of Cornell for Sardi's, a famous New York restaurant. It is now in the New York Public Library.

Although Cornell is buried in Tisbury, Massachusetts, there is a memorial stone for her in Buffalo. It is in the George W. Tifft plot at Forest Lawn Cemetery.

The Katharine Cornell Foundation

The Katharine Cornell Foundation was started with money earned from Barretts. The foundation closed in 1963. It gave its money to the Museum of Modern Art, Cornell University's theater department, and the Actor's Fund of America.

See also

In Spanish: Katharine Cornell para niños

In Spanish: Katharine Cornell para niños

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |