Lake Eyre basin facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Lake Eyre basin

|

|

|---|---|

Lake Hart is one of the smaller lakes in the basin

|

|

| Etymology: Lake Eyre; Edward John Eyre | |

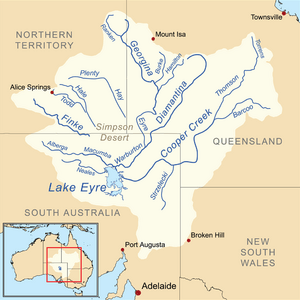

Map of the Lake Eyre Basin showing the major rivers

|

|

| Country | Australia |

| States and territories |

|

| Area | |

| • Total | 1,200,000 km2 (500,000 sq mi) |

The Lake Eyre Basin (pronounced AIR) is a huge area in Australia. It's like a giant bowl that collects water, covering almost one-sixth of the whole country. It's the biggest "endorheic basin" in Australia, meaning its rivers don't flow to the ocean. Instead, they flow inwards towards Kati Thanda-Lake Eyre.

This basin covers about 1,200,000 square kilometres (463,323 sq mi), which is a massive space. It includes large parts of inland Queensland, South Australia, the Northern Territory, and a bit of western New South Wales. It's one of the largest and least developed dry regions in the world.

Around 60,000 people live here, and it's home to lots of wildlife. There isn't much farming that uses irrigation, or big projects that change the natural flow of water. Most of the land (82%) is used for low-density grazing, where animals like cattle roam freely.

The basin started forming about 60 million years ago. Back then, it was mostly covered by forests and had many more lakes. Over millions of years, the climate slowly changed from wet to very dry. Now, most of the rivers in the Lake Eyre Basin are slow-moving and often completely dry for long periods.

When there are big floods in the northern part of the basin, the water flows south. It travels through major rivers like Cooper Creek, Georgina River, and Diamantina River towards Kati Thanda-Lake Eyre. This lake is the lowest point in Australia, about 16 metres (52 ft) below sea level. The floodwaters spread out across the flat land, filling waterholes and wetlands, and creating new river channels. This area is known as the Channel Country. Most of the rain that falls in the north never reaches the lake, which is 1,000 km away. The lake only fills up completely every now and then.

Managing this huge area can be tricky because it crosses four different states. People realized how important the basin's natural environment is. So, in 2001, the Lake Eyre Basin Intergovernmental Agreement was signed. This agreement helps make sure the river systems stay healthy for the future.

In 2014, the Queensland Government changed some laws that protect the rivers. Some environmental groups were worried these changes might allow for shale gas mining or fracking in the area.

Contents

Geology: How the Basin Formed

The Lake Eyre Basin began to form about 60 million years ago. This was during a time called the early Palaeogene. At that time, the land in south-eastern South Australia started to sink. Rivers then began to drop sediment (like sand and mud) into this large, shallow area.

Scientists think that a piece of an old ocean plate is slowly sinking deep inside the Earth under the basin. This sinking motion likely caused both the Lake Eyre Basin and the nearby Murray-Darling Basin to form. The basin is still slowly sinking and collecting more sediment.

For many millions of years, the Lake Eyre Basin had plenty of water and was mostly covered by forests. About 20 million years ago, huge shallow lakes formed, covering much of the area for about 10 million years. After that, Australia slowly drifted further north, and the climate became drier. The lakes and floodplains started to dry up. The current very dry climate, which led to the area becoming a desert, began about 2.6 million years ago during the start of the ice ages.

Geography: A Vast and Dry Landscape

The Lake Eyre Basin is enormous, covering about one-sixth of Australia. It's the largest "endorheic basin" in Australia, meaning its rivers don't flow to the sea. Instead, all the riverbeds in this huge, mostly flat, dry area lead inland towards Lake Eyre in central South Australia.

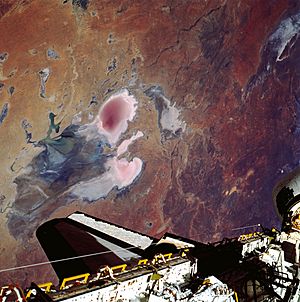

Lake Eyre itself is about 16 metres (52 ft) below sea level. Most of the time, it's just a dry salt pan. But when there's a lot of rain, it fills up. For a short time, the lake becomes full of life. Creatures that have been dormant (asleep) for a long time multiply quickly. Large groups of waterfowl (birds that live near water) arrive to feed and raise their young. Then, the water slowly evaporates again.

The Lake Eyre Basin has the lowest average yearly water flow of any major river basin in the world. None of the creeks or rivers in the basin flow all the time. They only flow after heavy rain, which is rare in Australia's dry interior. The average yearly rainfall around Lake Eyre is only 125 millimetres (4.9 in). However, the rate at which water evaporates is very high, about 3.5 metres (11 ft) per year.

Average rainfall figures can be misleading. Since 1885, the yearly rainfall over the 1,100,000 square kilometres (420,000 sq mi) of the Lake Eyre Basin has varied a lot. It was as low as 45 millimetres (1.8 in) in 1928 and over 760 millimetres (30 in) in 1974. Most of the water that reaches Lake Eyre comes from river systems in semi-dry inland Queensland, which is about 1,000 kilometres (620 mi) to the north.

To give you an idea of its size, the Lake Eyre Basin is roughly the same size as France, Germany, and Italy combined! It's a bit larger than the Murray-Darling Basin, another major river system in Australia. However, the Lake Eyre Basin has much less water. Even if all the water from the Murray-Darling River flowed into Lake Eyre, it wouldn't be enough to fill it. It would only keep up with the water that evaporates. In comparison, the Mississippi River in the USA could fill Lake Eyre in 22 days, and the Amazon River in South America could fill it in just 3 days!

Other important lakes in the basin include Lake Frome, Lake Yamma Yamma, and Lake Hart.

Major Rivers of the Basin

The Cooper Creek, Finke River, Georgina River, and Diamantina River are the four main rivers in the basin. Other desert rivers include the Hale River, Plenty River, and Todd River. These flow from the south-east of the Northern Territory towards the south. In the western parts of the basin, the Neales River and Macumba River flow into Lake Eyre.

The rivers in the basin have a gentle slope, so the water flows slowly. The water is also naturally cloudy or "turbid." Many of the major Lake Eyre Basin river systems are well-known. Because the basin is almost flat, rivers often split into many channels or spread out across floodplains. Water is lost through evaporation, by soaking into the ground, and in the many temporary wetland systems. This means that the amount of water flowing downstream is usually less than the amount upstream. Only in very wet years is there enough rain upstream for water to reach Lake Eyre itself.

The Finke River starts west of Alice Springs. It's thought to be the oldest riverbed in the world! Even though it only flows for a few days a year (and sometimes not at all), it's home to seven types of fish. Two of these fish are found nowhere else. The Finke River's waters disappear into the sands of the Simpson Desert. It's not certain if its water ever reaches Lake Eyre, though there's a story that it happened once in the early 1900s. In very extreme flood events, water from the Finke River can flow into the Macumba River, which then empties into Lake Eyre. This journey is about 750 km (470 mi) from where the river starts.

The Georgina River system begins on the Barkly Tableland, near the border between the Northern Territory and Queensland. This is north-west of Mount Isa and not far south of the Gulf of Carpentaria. In this wetter northern area, rainfall can be as high as 500 millimetres (20 in) per year. The Georgina River flows through countless channels, heading south through far-western Queensland for over 1,000 kilometres (620 mi). It eventually reaches Goyder Lagoon in the north-eastern corner of South Australia.

Australia's early bush poets made the Diamantina River famous, using it as a symbol of the remote outback. It also starts in northern Queensland, roughly between Mount Isa and Winton. It flows 800 kilometres south and west through Birdsville and the Channel Country. It then joins the Georgina River at Goyder Lagoon. If there's enough water, it continues down Warburton Creek towards Lake Eyre.

Of all the Lake Eyre Basin river systems, Cooper Creek is the most famous. This is partly because explorers Burke and Wills died along Cooper Creek. It starts as two rivers in central Queensland: the Thomson (between Longreach and Charters Towers) and the Barcoo (around Barcaldine). Cooper Creek spreads out into a huge area of winding, temporary channels. It flows south into the far south-west corner of Queensland before turning west into South Australia towards Lake Eyre. It can take almost a year for water to travel from the headwaters (where the river begins) to Lake Eyre. In most years, no water reaches the lake. Instead, it soaks into the earth, fills channels and many permanent waterholes, or simply evaporates. Water from Cooper Creek reached Lake Eyre in 1990 and then not again until 2010.

Deserts of the Basin

Several deserts have formed in the Lake Eyre Basin. These include the Sturt Stony Desert, Tirari Desert, and the Strzelecki Desert. These deserts are likely the largest source of airborne dust in the southern hemisphere.

History and Indigenous Connections

The Wangkangurru language is an Australian Aboriginal language spoken on Wangkangurru country. It is closely related to the Arabana language of South Australia. The Wangkangurru language region traditionally covered the South Australian-Queensland border area. This included Birdsville and stretched south towards Innamincka and Lake Eyre. It also covered parts of the Shire of Diamantina and the Outback Communities Authority of South Australia.

Indigenous Australians have lived with the natural cycles of this land for thousands of years. The traditional owners of the land are very protective of its natural systems.

Management and Protection Efforts

Managing the Lake Eyre Basin has been a challenge because it crosses four different states. Each state has its own laws and rules. As people learned more about the basin's important ecosystems, it became clear that a shared plan was needed. This was especially true after seeing challenges in managing other river systems during dry periods.

In 2001, the Lake Eyre Basin Intergovernmental Agreement was signed. This agreement was created to make sure the Lake Eyre Basin river systems remain healthy and sustainable. It aims to prevent or fix any problems that might cross state borders. The Lake Eyre Basin Ministerial Forum was set up to make decisions about the agreement. This forum also created a Community Advisory Committee to get advice from local people and a Scientific Advisory Panel for expert scientific and technical advice. In 2018, the Ministerial Forum agreed to review the agreement again.

In 2014, the Queensland Government changed some laws that protect the rivers and floodplains. According to environmentalists, these changes could potentially allow for shale gas mining or fracking in the area.

Protected Areas in the Basin

Several important protected areas have been created within the Lake Eyre Basin. These include:

- Kati Thanda-Lake Eyre National Park

- Strzelecki Regional Reserve

- Witjira National Park

- Sturt National Park

- Diamantina National Park

- Simpson Desert National Park

River Diversion Ideas

The Bradfield Scheme was a big idea proposed by Dr John Bradfield in 1938. It suggested using large pipes, tunnels, pumps, and dams. The goal was to move water from the monsoon-fed Tully, Herbert, and Burdekin rivers into the Thomson River in Queensland. Other less developed ideas have also been suggested over time to divert river or sea water into the Lake Eyre Basin.

Fauna: Fish in the Basin

The Lake Eyre Basin is home to 27 different types of fish. Thirteen of these fish species are "endemic," meaning they are found nowhere else in the world. The largest fish species found here is the Macquaria, which can weigh up to about 3 kilograms (6.6 lb).

Images for kids

- Dr Vincent Kotwicki: Floods of Lake Eyre - an interesting site with much data, including Lake Eyre inflows 1885–2012.

25°59′49″S 137°59′57″E / 25.99686697°S 137.99905382°E