Queen conch facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Lobatus gigas |

|

|---|---|

|

|

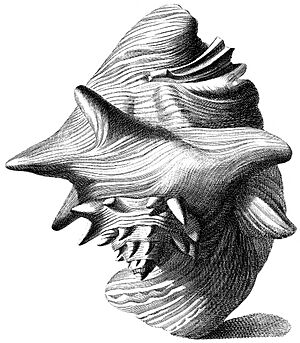

| Shell of Lobatus gigas (ventral view) | |

|

|

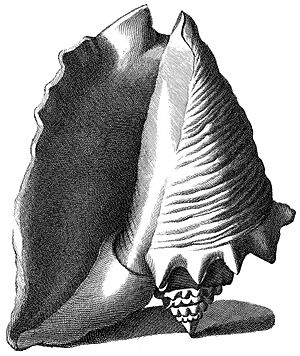

| Shell of Lobatus gigas (dorsal view) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| (unranked): |

clade Caenogastropoda

clade Hypsogastropoda clade Littorinimorpha |

| Family: |

Strombidae

|

| Genus: |

Lobatus

|

| Species: |

L. gigas

|

| Binomial name | |

| Lobatus gigas (Linnaeus, 1758)

|

|

| Synonyms | |

|

Strombus gigas Linnaeus, 1758 |

|

The Lobatus gigas, often called the queen conch, is a very large, edible sea snail. It's a type of gastropod mollusc that belongs to the family of true conches, the Strombidae. This amazing creature is one of the biggest molluscs found in the tropical northwestern Atlantic Ocean. You can find it from Bermuda all the way down to Brazil. Its shell can grow to be as long as 35.2 centimeters (about 13.9 inches)!

Contents

Anatomy of the Queen Conch

The Shell

The shell of a grown queen conch is usually between 15 and 31 centimeters (6 to 12 inches) long. The biggest one ever found was 35.2 centimeters (13.9 inches). This shell is very strong and heavy. It has 9 to 11 spirals and a wide, thick outer lip.

A special feature of the shell is a small notch on the outer lip. The conch's left eyestalk sticks out through this notch.

The spire is the pointy top part of the shell. It includes all the spirals except the very last and largest one, called the body whorl. The spire of the queen conch is usually longer than those of other conch snails.

The inside of the shell, near the opening (called the aperture), is usually a pale pink color. It can also be cream, peach, or yellow, and sometimes even a deep magenta or red. The outer layer of the shell, called the periostracum, is thin and light brown.

The way a queen conch shell looks isn't just decided by its genes. Things like where it lives, what it eats, the water temperature, and how deep it is can change its shape. Even predators can affect it! Young conches grow stronger shells when they are around predators. Conches in deeper water also grow wider, thicker shells with fewer, longer spines.

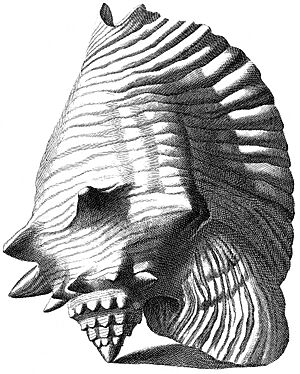

Young queen conch shells look very different from adult shells. They don't have the wide, flared outer lip. Instead, their shells are simple and pointed, like a cone. In Florida, young queen conches are called "rollers." This is because waves can easily roll their shells. Adult shells are too heavy and uneven to roll easily. As they grow, subadult shells get a thin flared lip that keeps getting thicker.

Conch shells are mostly made of calcium carbonate (about 95%) and a small amount of organic material (about 5%).

Old Drawings of Shells

Old books from the 1700s and 1800s show detailed drawings of queen conch shells. These drawings highlight the bumpy spire and the wide, wing-like outer lip.

Soft Parts of the Conch

The queen conch has a long, stretchy snout with two eyestalks coming from its base. At the end of each eyestalk is a large, well-developed eye with a black pupil and a yellow iris. There's also a small sensory tentacle near the eye. If an eye is lost, it can grow back completely!

Inside the conch's mouth is a radula. This is like a tough ribbon covered with tiny teeth. Both the snout and eyestalks have dark spots. The mantle, which covers the internal organs, is dark at the front and light gray at the back. The mantle collar is usually orange. The siphon, which helps the conch breathe, is also orange or yellow.

Foot and How It Moves

The queen conch has a large, strong foot with brown spots. A dark brown, sickle-shaped flap called an operculum is attached to the back of the foot. This operculum is reinforced by a strong central rib.

The conch moves in a very unusual way, first described in 1922. It pushes the pointy end of its operculum into the ground. Then, it stretches its foot forward, lifts its shell, and throws it forward in a "leaping" motion. This movement is a bit like pole vaulting! This special way of moving helps the conch climb even vertical surfaces. It might also help it avoid predators by not leaving a continuous trail of chemicals on the ground.

Life Cycle of the Queen Conch

Queen conchs are either male or female. Females are usually larger than males. After internal fertilization, the female lays her eggs in long, jelly-like strings. These strings can be as long as 75 feet! She lays them on sandy areas or in seagrass. The sticky egg strings coil up and mix with sand, forming compact egg masses.

The number of eggs in each mass changes depending on how much food is available and the temperature. Females usually lay 8 to 9 egg masses per season. Each mass can have between 180,000 and 460,000 eggs, but sometimes even up to 750,000! Queen conch females can lay eggs many times during the reproductive season, which lasts from March to October. The busiest time for laying eggs is from July to September.

Queen conch embryos hatch 3 to 5 days after the eggs are laid. When they hatch, the tiny protoconch (embryonic shell) is clear and off-white with small bumps. The newly hatched conch is called a veliger larva. It has two lobes and spends several days floating in the plankton, eating tiny plants called phytoplankton.

After about 16 to 40 days, the larva changes into a young conch. It then lives on the ocean floor (the benthic zone) for the rest of its life. For its first year, it usually stays buried in the sand.

Queen conchs become old enough to reproduce at about 3 to 4 years of age. By then, their shells are nearly 180 mm (7 inches) long, and they can weigh up to 5 pounds. Conchs usually live for about 7 years, but in deeper waters, they can live for 20 to 30 years, and some may even reach 40 years old! Older conchs with thicker shells are thought to have a lower chance of dying.

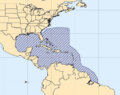

Where Queen Conchs Live

The queen conch lives in the tropical Western Atlantic Ocean. You can find it along the coasts of North and Central America, especially in the wider Caribbean region.

They are found in many places, including: Aruba, Barbados, The Bahamas, Belize, Bermuda, parts of Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, the Dominican Republic, Panama, Honduras, Jamaica, Martinique, parts of Mexico, Puerto Rico, Saint Barthélemy, Grenada, Cuba, the Turks and Caicos Islands, Florida in the United States, Venezuela, and the Virgin Islands.

What Queen Conchs Eat

For a long time, people thought that conch snails were meat-eaters. However, later studies showed that this was wrong. Queen conchs are actually herbivores, meaning they eat plants.

Like other conch snails, Lobatus gigas is a specialized plant-eater. It feeds on large seaweeds (like red algae), seagrass, and tiny single-celled algae. They also sometimes eat decaying plant matter. One of their favorite foods is a green seaweed called Batophora oerstedii.

Uses of the Queen Conch

Conch meat has been eaten for hundreds of years. It's a traditional and important food in many Caribbean islands and Southern Florida. People eat it raw, marinated, chopped, or minced in many dishes. These include salads, chowder, fritters, soups, stews, and pâtés. In Spanish-speaking areas, the meat is called lambí.

While mostly eaten by people, conch meat is sometimes used as fishing bait. The queen conch is one of the most important fishing resources in the Caribbean. In 1992, its harvest was worth US$30 million, growing to $60 million in 2003. However, the amount of conch harvested has gone down a lot in recent years.

Queen conch shells were used in many ways by Native Americans and Caribbean Indians. Groups like the Tequesta, Carib, Arawak, and Taíno used conch shells to make tools like knives, axe heads, and chisels. They also made jewelry, cookware, and used them as blowing horns. In ancient Mesoamerica, the Aztecs used conch shells in jewelry and believed the sound of conch trumpets was divine. The Maya used them as hand protectors during combat.

When explorers brought queen conch shells to Europe, they quickly became popular decorations. In the late 1600s, people used them to decorate fireplaces and English gardens. Today, queen conch shells are mainly used for crafts. They are made into cameos, bracelets, and lamps. They are also used as doorstops or decorations in homes. The export of these shells is now controlled by the CITES agreement to protect the species. In modern culture, queen conch shells often appear on coins and stamps.

Very rarely (about 1 in 10,000 conchs), a special conch pearl can be found inside the shell. These pearls come in different colors, matching the inside of the shell. Pink ones are the most valuable. These pearls are considered semi-precious and are popular souvenirs for tourists. The best ones are used to make necklaces and earrings. Unlike most pearls, conch pearls do not have a shiny, iridescent layer called nacre.

Scientists at MIT are studying the unique structure of the conch shell.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Caracol rosado para niños

In Spanish: Caracol rosado para niños