Memphis, Tennessee facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Memphis

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|||

| Nickname(s):

Bluff City, Home of the Blues, Grind City, The 901

|

|||

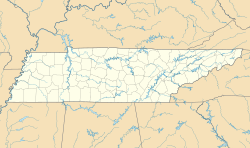

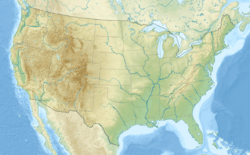

| Country | United States | ||

| State | Tennessee | ||

| County | Shelby | ||

| Founded | May 22, 1819 | ||

| Incorporated | December 19, 1826 | ||

| Founded by | John Overton, James Winchester, and Andrew Jackson | ||

| Named for | Memphis, Egypt | ||

| Area | |||

| • City | 302.55 sq mi (783.66 km2) | ||

| • Land | 294.92 sq mi (763.83 km2) | ||

| • Water | 7.63 sq mi (19.77 km2) | ||

| Elevation | 337 ft (103 m) | ||

| Population

(2020)

|

|||

| • City | 633,104 | ||

| • Rank | 68th in North America 28th in the United States 2nd in Tennessee |

||

| • Density | 2,146.71/sq mi (828.85/km2) | ||

| • Urban | 1,056,190 (US: 45th) | ||

| • Urban density | 2,149.9/sq mi (830.1/km2) | ||

| • Metro | 1,337,779 (US: 43rd) | ||

| Demonym(s) | Memphian | ||

| GDP | |||

| • Metro | 2.934 billion (2023) | ||

| Time zone | UTC−6 (CST) | ||

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) | ||

| ZIP Codes |

ZIP Codes

|

||

| Area code | 901 | ||

| FIPS code | 47-48000 | ||

Memphis is a big city in the U.S. state of Tennessee. It's the main city of Shelby County, located in the very southwest part of the state. Memphis sits right along the famous Mississippi River. In 2020, about 633,104 people lived there, making it the second-largest city in Tennessee, after Nashville.

Memphis is known by many cool nicknames like "Bluff City" because it's built on high ground, and "Home of the Blues" for its amazing music history. It's also called "Grind City" and "The 901" (after its area code). The city is a major center for transportation and shipping, especially with FedEx having its main air hub here. Memphis has played a big part in American history and culture, especially in music and civil rights.

Contents

History of Memphis

Early Beginnings

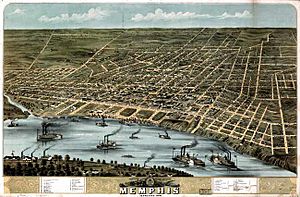

The area where Memphis is today has been a home for people for thousands of years. It's a great spot because it's on high bluffs, safe from the Mississippi River's floods. In 1541, a Spanish explorer named Hernando de Soto was one of the first Europeans to visit this area. Later, both Spain and the United States wanted to control this important spot.

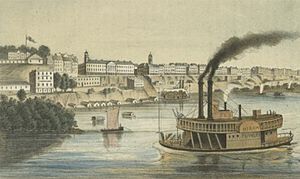

In 1795, the Spanish built a fort called Fort San Fernando de las Barrancas here. But by 1797, the United States gained control of the land. The city of Memphis was officially founded on May 22, 1819, by John Overton, James Winchester, and Andrew Jackson. They named it after the ancient city of Memphis, Egypt on the Nile River.

Growing in the 1800s

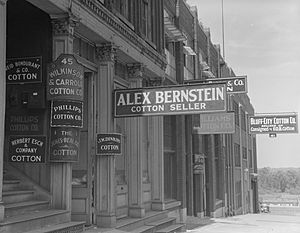

Memphis quickly became a busy center for trade and transportation. It was a major market for cotton, which was grown on nearby plantations. Many African Americans were forced to work on these plantations as slaves. Memphis also became a big market for the slave trade. In 1857, the Memphis and Charleston Railroad was finished. This connected Memphis to the Atlantic Coast, making it easier to ship cotton to places like England.

In the 1850s and 1860s, many new people moved to Memphis. A lot of them were immigrants from Ireland and Germany. These new groups changed the city's population a lot.

During the American Civil War, Tennessee joined the Confederacy. But in June 1862, Union forces captured Memphis. The city stayed under Union control for the rest of the war. Because Memphis was a Union supply base, it continued to do well economically. Many enslaved people escaped from nearby plantations and came to Memphis for protection. This caused the Black population in the city to grow a lot.

After the Civil War

After the war, there were some tough times. In May 1866, there were riots in Memphis. White mobs, including police, attacked Black residents. Many Black people left Memphis after this violence. The population changed again, with fewer Black residents in the city by 1870. These riots, and others like them, helped push the U.S. Congress to pass important laws like the Reconstruction Act.

In the 1870s, Memphis faced a big challenge: several yellow fever outbreaks. This disease was carried by people traveling on the river. The worst epidemic was in 1878. Thousands of people died, and many more fled the city. Memphis became almost bankrupt because of this. The city even lost its official city charter for a while. However, this disaster also led to good changes. Memphis started to improve its sanitation and water systems, becoming a leader in public health.

The yellow fever epidemics changed Memphis's population. Many wealthier people left, and the city became home to more working-class white and Black Southerners.

The 1900s and Civil Rights

In the 1900s, Memphis became the world's largest market for cotton and hardwood lumber. It also grew a lot in population. From the 1910s to the 1950s, a political leader named E. H. Crump had a lot of power in Memphis. He helped make the city more efficient, but some people felt that the city government didn't represent everyone fairly.

Memphis was a very important place during the American Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s. Many African Americans in the city faced segregation and unfair treatment. In 1968, sanitation workers, mostly African American, went on strike for better pay and working conditions. Martin Luther King Jr. came to Memphis to support them. Sadly, he was assassinated on April 4, 1968, at the Lorraine Motel.

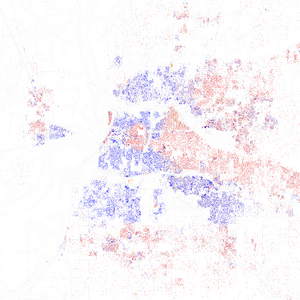

After King's death, there were riots in the city. Many middle-class families started to move out of the city to the suburbs. Today, Memphis has a majority-Black population, but the wider metropolitan area has a slight majority of white residents.

Memphis has produced many famous musicians, including Elvis Presley, Jerry Lee Lewis, Johnny Cash, B.B. King, Isaac Hayes, and Aretha Franklin. They helped shape American music.

Geography of Memphis

Memphis is in the southwest corner of Tennessee. It covers about 302.55 square miles (783.66 square kilometers). Most of this area is land, with a small part being water.

City Views

Downtown Memphis sits on a bluff overlooking the Mississippi River. The city and its surrounding areas spread out into suburbs. Memphis is a major transportation hub. It has two main Interstate Highways, I-40 and I-55, that cross the Mississippi River. It's also a big center for barge traffic on the river, and has a huge airport for cargo.

In 2013, Forbes magazine said Memphis was one of the top 15 cities in the U.S. with a growing downtown area. Also, USA Today readers voted Beale Street as America's Best Iconic Street and Graceland as the Best Iconic American Attraction.

Riverfront Fun

The Memphis Riverfront stretches along the Mississippi River. The River Walk is a park system that connects downtown Memphis. It goes from Mississippi River Greenbelt Park in the north to Tom Lee Park in the south. It's a great place for walks and enjoying the river views.

Water Supply

Memphis gets its drinking water from a natural underground source called the "Memphis Aquifer." This water is very pure and soft. It's located deep underground, between 350 and 1100 feet. Experts estimate it holds a huge amount of water, more than 100 trillion gallons!

Memphis Weather

Memphis has a humid subtropical climate, which means it has four clear seasons. Summers are hot and humid, with temperatures often around 82.7°F (28.2°C) in July. Thunderstorms are common in the afternoon during summer, but they usually don't last long. Autumn is usually drier and mild. Winters are mild to chilly, with January temperatures around 41.2°F (5.1°C). Snow doesn't happen very often, but ice storms can be a problem. Severe thunderstorms can happen any time of year, especially in spring.

The highest temperature ever recorded was 108°F (42°C) in 1980, and the lowest was -13°F (-25°C) in 1963. Memphis gets a good amount of rain throughout the year.

People of Memphis

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1850 | 8,841 | — | |

| 1860 | 22,623 | 155.9% | |

| 1870 | 40,226 | 77.8% | |

| 1880 | 33,592 | −16.5% | |

| 1890 | 64,495 | 92.0% | |

| 1900 | 102,320 | 58.6% | |

| 1910 | 131,105 | 28.1% | |

| 1920 | 162,351 | 23.8% | |

| 1930 | 253,143 | 55.9% | |

| 1940 | 292,942 | 15.7% | |

| 1950 | 396,000 | 35.2% | |

| 1960 | 497,524 | 25.6% | |

| 1970 | 623,988 | 25.4% | |

| 1980 | 646,174 | 3.6% | |

| 1990 | 610,337 | −5.5% | |

| 2000 | 650,100 | 6.5% | |

| 2010 | 646,889 | −0.5% | |

| 2020 | 633,104 | −2.1% | |

| 2023 (est.) | 618,639 | −4.4% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census 2010–2020 |

|||

According to the 2020 United States census, the population of Memphis was 633,104. The largest group was Black or African American people, making up about 61.28% of the population. White people made up about 23.94%. There are also growing communities of Hispanic or Latino people (9.82%) and Asian people (1.82%).

The Memphis Metropolitan Area is much larger, with a population of over 1.3 million people. This area includes parts of Tennessee, Mississippi, and Arkansas.

Religions in Memphis

Memphis is home to many different religions and places of worship. You can find churches for various Christian groups, as well as synagogues for Jewish people, and mosques for Muslims. There are also temples for Hindus and Buddhists.

The international headquarters of the Church of God in Christ, a large Christian group, is in Memphis. Their Mason Temple is famous because Martin Luther King Jr. gave his last speech there in 1968. The National Civil Rights Museum in Memphis honors people with Freedom Awards at this temple every year.

Memphis also has some very large churches, like Bellevue Baptist Church. There are two cathedrals, which are main churches for Catholic and Episcopal groups. Temple Israel is one of the largest Reform synagogues in the country. Memphis has a diverse religious community.

Memphis Economy

Memphis's location in the center of the country has helped its businesses grow. It's on the Mississippi River and has many major railroads and highways. This makes it a great place for transportation and shipping.

The Memphis International Airport is the world's busiest airport for cargo (shipping goods). This is because FedEx Express has its main global hub there. The International Port of Memphis is also one of the busiest inland water ports in the U.S.

Memphis is home to several large companies, including FedEx, International Paper, and AutoZone. The city also has a growing entertainment and film industry. Many movies and TV shows have been filmed in Memphis.

Arts and Culture in Memphis

Fun Events

One of the biggest celebrations in Memphis is Memphis in May. This month-long event includes:

- The Beale Street Music Festival, with lots of live music.

- International Week, celebrating different cultures.

- The World Championship Barbecue Cooking Contest, the biggest pork barbecue contest in the world.

- The Great River Run.

Other cool events include:

- Africa in April, a festival celebrating African history and culture.

- The Memphis Italian Festival in May-June, with Italian food, music, and games like bocce.

- Carnival Memphis, a series of parties and festivities in June.

- The Cooper-Young Festival in September, showcasing local music and art.

- Several film festivals, like Indie Memphis Film Festival and Outflix.

- The Memphis International Jazz Festival in November.

- The International Blues Awards, celebrating achievements in blues music.

Music City

Memphis is super famous for its music. It's the birthplace of many American music styles, like Memphis soul, Memphis blues, gospel, rock n' roll, and Memphis rap.

Many legendary musicians started their careers in Memphis:

Beale Street is a historic landmark known for its blues clubs. Sam Phillips' Sun Studio is still open for tours. Elvis, Johnny Cash, and Jerry Lee Lewis all made their first recordings there. Stax Records created a unique 1960s soul music sound. Memphis also has a strong influence on power pop and Memphis rap music.

Delicious Food

Memphis is famous for its Memphis-style barbecue. This style is known worldwide, especially because of the World Championship Barbecue Cooking Contest.

Some famous Memphis restaurants include:

- Alcenia's, known for soul food.

- Charlie Vergos' Rendezvous, a barbecue spot visited by many celebrities.

- Dyer's Burgers, famous for deep-fried burgers.

- Gus's World Famous Fried Chicken, which started nearby and has grown across the country.

Besides barbecue, Memphis is also known for its Fried chicken and chicken wings with a special "Honey Gold" sauce.

Art and Literature

Memphis has a growing art scene. The South Main Arts District and Broad Avenue are areas where artists live and work. The city also has non-commercial art spaces like Marshall Arts gallery.

Famous writers from Memphis include Shelby Foote, a Civil War historian, and John Grisham, who sets many of his books in the city. Many other books and stories are also set in Memphis.

Tourist Attractions

Memphis has many exciting places to visit:

- Beale Street: A historic street with live music, bars, and clubs.

- Graceland: The former home of Elvis Presley, now a museum. It's very popular!

- Memphis Zoo: Home to many animals from around the world.

- Peabody Hotel: Famous for its "Peabody Ducks" that march through the lobby.

- Sun Studio: Where many music legends made their first recordings.

- Orpheum Theatre: Hosts Broadway shows and other performances.

- Memphis Pyramid: A huge pyramid that now holds the world's largest Bass Pro Shops, an observation deck, restaurants, and more.

Other attractions include the Simmons Bank Liberty Stadium and FedExForum for sports, and Mississippi riverboat cruises.

Museums and Art Collections

- National Civil Rights Museum: Located at the Lorraine Motel, where Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated. It tells the story of the American civil rights movement.

- Memphis Brooks Museum of Art: The oldest and largest art museum in Tennessee, with art from different time periods.

- Belz Museum of Asian and Judaic Art: Features a large collection of Asian and Jewish art.

- Dixon Gallery and Gardens: Known for French and American impressionist art and beautiful gardens.

- Children's Museum of Memphis: Offers fun, hands-on activities for kids.

- Pink Palace Museum and Planetarium: A science and history museum with a large planetarium and an IMAX theater.

- Mud Island: A park with a walking trail that has a scale model of the Mississippi River.

- Mississippi River Museum: On Mud Island, it focuses on the history of the Mississippi River.

- Stax Museum: Located at the former Stax Records studio, celebrating soul music.

- Chucalissa Indian Village: An ancient Native American village site, now a museum run by the University of Memphis.

Cemeteries

Memphis has several important cemeteries. The Memphis National Cemetery is a U.S. National Cemetery. Historic Elmwood Cemetery is one of the oldest garden cemeteries in the South. Memorial Park Cemetery has unique sculptures. Elvis Presley was first buried in Forest Hill Cemetery, but his body was later moved to Graceland.

Sports in Memphis

Memphis is home to the Memphis Grizzlies, a professional basketball team in the NBA. It's the only "big four" major sports league team in the city.

Other sports teams include:

- Memphis Redbirds: A minor league baseball team, connected to the St. Louis Cardinals.

- Memphis Hustle: A basketball team in the NBA G League.

- Memphis Showboats: A football team in the United Football League.

The Memphis Tigers college basketball and football teams from the University of Memphis are very popular. The basketball team has a strong history of success. The city also hosts the annual St. Jude Classic golf tournament and tennis events.

Memphis has a rich history in pro wrestling, with famous figures like Jerry "The King" Lawler coming from the city.

Parks and Recreation

Memphis has many beautiful parks for everyone to enjoy. Some of the major parks include:

- W.C. Handy Park

- Tom Lee Park

- Audubon Park

- Overton Park, which has the Old Forest Arboretum

- The Lichterman Nature Center, a place to learn about nature

- The Memphis Botanic Garden

- Jesse H Turner Park

Shelby Farms park, located on the eastern edge of the city, is one of the largest urban parks in the United States. It's a huge space for outdoor activities.

Education in Memphis

Schools for Kids

Memphis is served by Memphis-Shelby County Schools. In 2013, the city's school system merged with the Shelby County system. This school system runs many elementary, middle, and high schools.

There are also many private schools in the Memphis area that prepare students for college. Some of these include:

- Briarcrest Christian School

- Christian Brothers High School

- Hutchison School

- Memphis University School

- Lausanne Collegiate School

Colleges and Universities

Memphis has several colleges and universities:

- The University of Memphis

- Rhodes College

- Christian Brothers University

- LeMoyne–Owen College

- University of Tennessee Health Science Center

The University of Tennessee College of Dentistry was founded in 1878, making it one of the oldest dental colleges in the South.

Media in Memphis

Newspapers

Memphis has several newspapers that keep people informed:

- The Commercial Appeal: A daily newspaper, started in 1840.

- Memphis Flyer: A weekly newspaper.

- Memphis Tri-State Defender: Another weekly newspaper.

Television Stations

Memphis has many local TV channels that are part of national networks:

- WREG (Channel 3): A CBS affiliate.

- WMC (Channel 5): An NBC affiliate.

- WKNO (Channel 10): A PBS station, offering public broadcasting.

- WHBQ (Channel 13): A Fox affiliate.

- WATN (Channel 24): An ABC affiliate.

- WLMT (Channel 30): A The CW affiliate.

Radio Stations

Memphis has many radio stations playing different types of music and shows. Some popular FM stations include:

- WQOX (88.5 FM): Urban adult contemporary.

- WKNO (91.1 FM): Public radio and classical music.

- WHRK (97.1 FM): Hip hop music.

- WLFP (99.7 FM): Country music.

- KJMS (101.1 FM): Urban adult contemporary.

- WEGR (102.7 FM): Classic rock.

Some popular AM stations include:

- WHBQ (560 AM): Sports radio.

- WREC (600 AM): Talk radio.

- WDIA (1070 AM): Urban oldies.

- WLOK (1340 AM): Urban gospel.

Getting Around Memphis

Highways

Memphis is a major crossroads for highways. Interstate 40 and Interstate 55 are the main highways that cross the Mississippi River here. I-40 goes east to Nashville and North Carolina, and west to Little Rock and Los Angeles. I-55 goes north to St. Louis and Chicago, and south to Jackson and New Orleans.

There's also Interstate 240, which is a loop around the city, and Interstate 269, a larger outer loop. A new highway, Interstate 22, connects Memphis to Birmingham, Alabama. Another proposed highway, Interstate 69, would connect Memphis to Canada and Mexico in the future.

Memphis uses technology to help with its roads. They use machine learning to find potholes and fix them faster!

Public Transportation

The Memphis Area Transit Authority (MATA) provides bus services and a historic streetcar system called the MATA Trolley. You can also find intercity bus services like Greyhound Lines in Memphis.

Trains

A lot of train freight moves through Memphis because it has two major railroad crossings over the Mississippi River. These crossings connect many important east-west and north-south train lines.

Memphis used to have two big passenger train stations. Today, only the Memphis Central Station is still used. The only passenger train service is the daily City of New Orleans train, run by Amtrak, which travels between Chicago and New Orleans.

Airports

Memphis International Airport is the global "SuperHub" for FedEx Express. It's the busiest airport in the world for cargo! It also has passenger flights from airlines like Southwest Airlines, American Airlines, and Delta Air Lines.

River Port

Memphis has the second-busiest cargo port on the Mississippi River. This port is also the fourth-busiest inland port in the United States. It's a very important place for shipping goods by water.

Bridges

Four bridges cross the Mississippi River at Memphis. Two are for trains: the Frisco Bridge (built in 1892) and the Harahan Bridge (built in 1916). The Harahan Bridge also has a walkway for bikes and pedestrians. Two bridges are for cars: the Memphis-Arkansas Memorial Bridge (built in 1949, part of I-55) and the Hernando de Soto Bridge (built in 1973, part of I-40).

Utilities

Memphis gets its electricity, natural gas, and water from the Memphis Light, Gas and Water Division (MLGW). This is the largest city-owned utility company in the U.S. They get most of their electricity from the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) and pump their own fresh water from the Memphis Aquifer.

Notable People from Memphis

Many famous people are from Memphis, including musicians, athletes, and writers.

Sister Cities

Memphis has sister cities around the world, which helps build friendships and understanding between different cultures:

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Memphis para niños

In Spanish: Memphis para niños

| DeHart Hubbard |

| Wilma Rudolph |

| Jesse Owens |

| Jackie Joyner-Kersee |

| Major Taylor |